NFC zu H-K-01

»KINDER-EUTHANASIE«

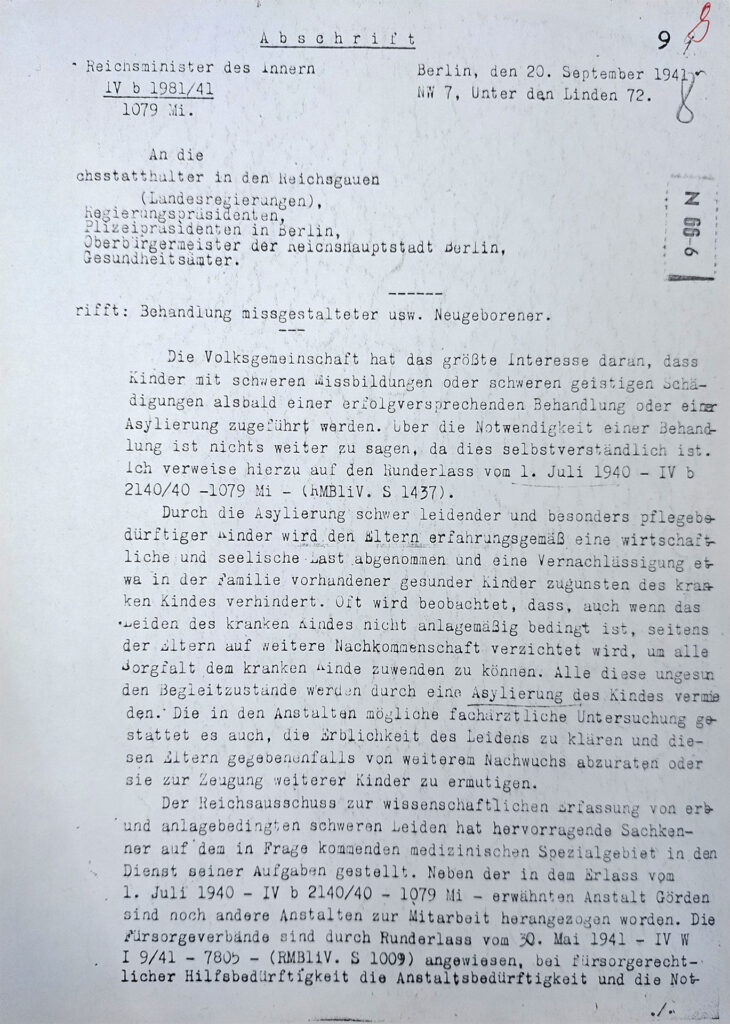

Ab 1940 nahmen in Görden, Dösen, Marsberg und in Wien (»Spiegelgrund«) die ersten »Kinderfachabteilungen« ihre Arbeit auf. Da der Meldepflicht kaum nachgekommen wurde und auch betroffene Eltern wenig Bereitschaft zur Teilnahme zeigten, verfasste das Reichsinnenministerium einen Erlass. Unter anderem wurde das Alter meldepflichtiger Kinder auf bis 16 Jahre hochgesetzt. In der Folge wurden weitere »Kinderfachabteilungen« eingerichtet und die Zahl der Kindermorde nahm zu. Die Lüneburger »Kinderfachabteilung« nahm ihren Betrieb auf und entwickelte sich zu einer der Hauptmordstätten.

KINDER-EUTHANASIE

In der Nazi-Zeit gibt es

Kinder-Fachabteilungen in Deutschland.

Das sind extra Stationen für Kinder

in einer Anstalt.

In Kinder-Fachabteilungen kommen

• Kinder mit Behinderung und

• Kinder mit seelischen Krankheiten.

Die Kinder sind ohne ihre Eltern dort.

Die ersten Kinder-Fachabteilungen gibt es

in diesen Städten:

• Görden.

• Dösen.

• Marsberg.

• Wien.

In der Nazi-Zeit sollen Eltern ihre Kinder

beim Amt melden,

• wenn die Kinder eine Behinderung haben.

• wenn die Kinder

eine seelische Krankheit haben.

Am Anfang gibt es nur wenige Meldungen.

Eltern wollen ihr Kind nicht

in die Kinder-Fachabteilung bringen.

Darum machen die Nazis strengere Regeln.

Jetzt gibt es mehr Meldungen.

Und es kommen mehr Kinder

in die Kinder-Fachabteilungen.

Man baut noch mehr Kinder-Fachabteilungen

in anderen Städten.

Zum Beispiel in der Anstalt in Lüneburg.

Viele Kinder werden in der Nazi-Zeit

in den Kinder-Fachabteilungen getötet.

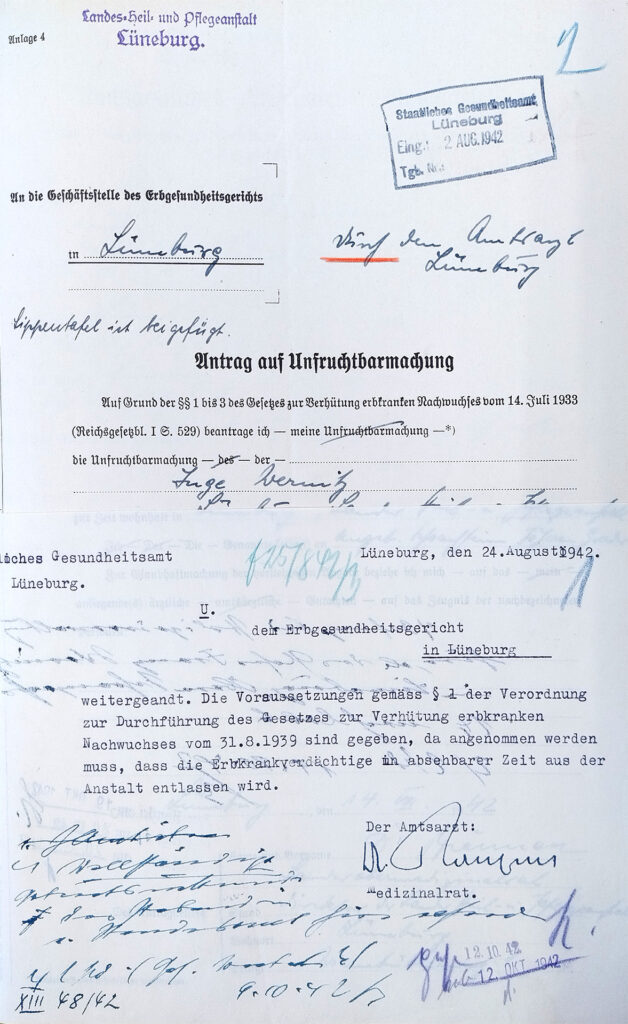

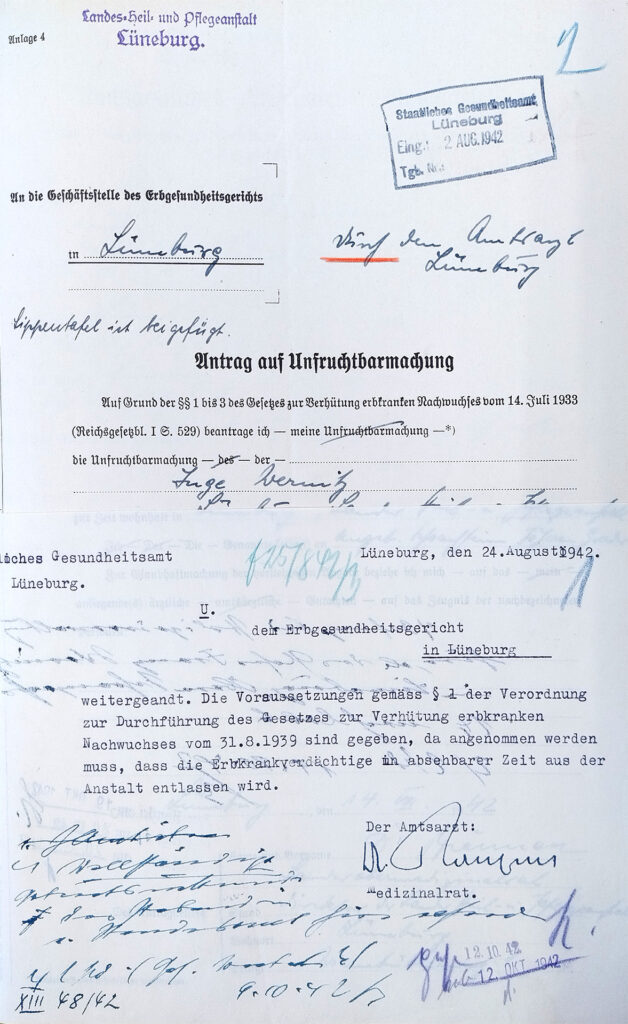

Auszug des Erlasses des Reichsministeriums des Innern vom 20.9.1941.

NLA Hannover Nds. 721 Lüneburg Acc. 8/98 Nr. 3/9.

Mit Nachdruck wurden zuständige Ämter angewiesen, ihre Meldepflicht zu erfüllen. Sie sollten Eltern überzeugen, dass die Maßnahme gut für die Gemeinschaft und die Familien sei. Offenbar trafen die Ergebnisse einer Befragung von Ewald Meltzer aus dem Jahr 1920 nicht zu. Die erst 1925 veröffentlichte Studie besagte, dass 78 Prozent der Eltern die »Erlösung« ihrer Kinder mit Beeinträchtigungen wünschten. Doch das entsprach nicht der Wahrheit.

In der Nazi-Zeit haben Ämter eine Aufgabe:

Sie müssen Kinder mit Behinderungen oder Krankheiten melden.

Gemeldete Kinder kommen dann

in eine Kinder-Fachabteilung.

Dort werden die Kinder ermordet.

Die Ämter müssen auch mit den Eltern

über diese Meldung reden.

Eltern sollen denken:

Es ist gut,

wenn das Kind in eine Kinder-Fachabteilung kommt.

Aber die Eltern denken so nicht.

Gemeldete Kinder und Jugendliche wurden vom »Reichsausschuss« und von Ärzt*innen vor Ort untersucht. Die Bewertung, ob ein Kind oder Jugendlicher »entwicklungs- und bildungsfähig« war, entschied über Leben und Tod. »Unfähige« wurden ermordet, ihre Gehirne dienten der medizinischen Forschung.

Für die »Kinder-Euthanasie« wurden mehr als 30 »Kinderfachabteilungen« in Heimen, Krankenhäusern und Anstalten eingerichtet. Nicht alle existierten im gleichen Zeitraum. Etwa 6.800 in »Kinderfachabteilungen« gestorbene Kinder und Jugendliche sind bekannt, mindestens 6.500 von ihnen wurden ermordet.

Auch außerhalb der »Kinderfachabteilungen« kam es vielerorts zu »Kinder-Euthanasie« unbekannten Ausmaßes.

In der Nazi-Zeit muss man Kinder melden,

• wenn sie eine Behinderung haben.

• wenn sie eine seelische Krankheit haben.

Ärzte prüfen dann:

• Kann das Kind lernen?

• Kann das Kind weiterentwickeln?

Wenn das Kind lernen kann, darf es leben.

Wenn das Kind nicht lernen kann,

wird es ermordet.

Die Prüfung machen die Ärzte

in den Kinder-Fachabteilungen.

Die Bewertung macht der Reichsausschuss.

In der Kinder-Fachabteilung werden

Kinder und Jugendliche ermordet.

Danach untersuchen Ärzte die Gehirne

von den toten Kindern.

Heute wissen wir:

6 800 Kinder sind in der Nazi-Zeit

in Kinder-Fachabteilungen gestorben.

6 500 Kinder von diesen Kindern wurden

in Kinder-Fachabteilungen ermordet.

Wie die anderen 300 Kinder gestorben sind,

weiß man nicht genau.

vielleicht sind sie an einer Krankheit gestorben.

Vielleicht wurden sie aber auch ermordet.

Aber die Nazis haben Kinder nicht nur

in Kinder-Fachabteilungen ermordet.

Die Nazis haben Kinder und Jugendliche

auch an anderen Orten getötet.

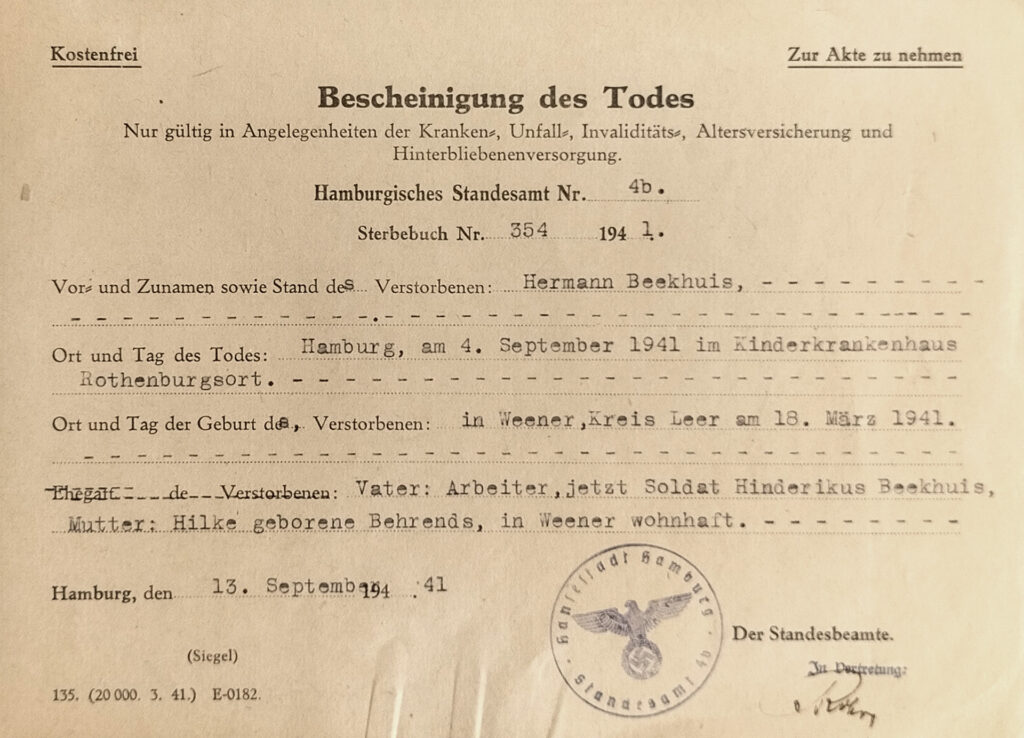

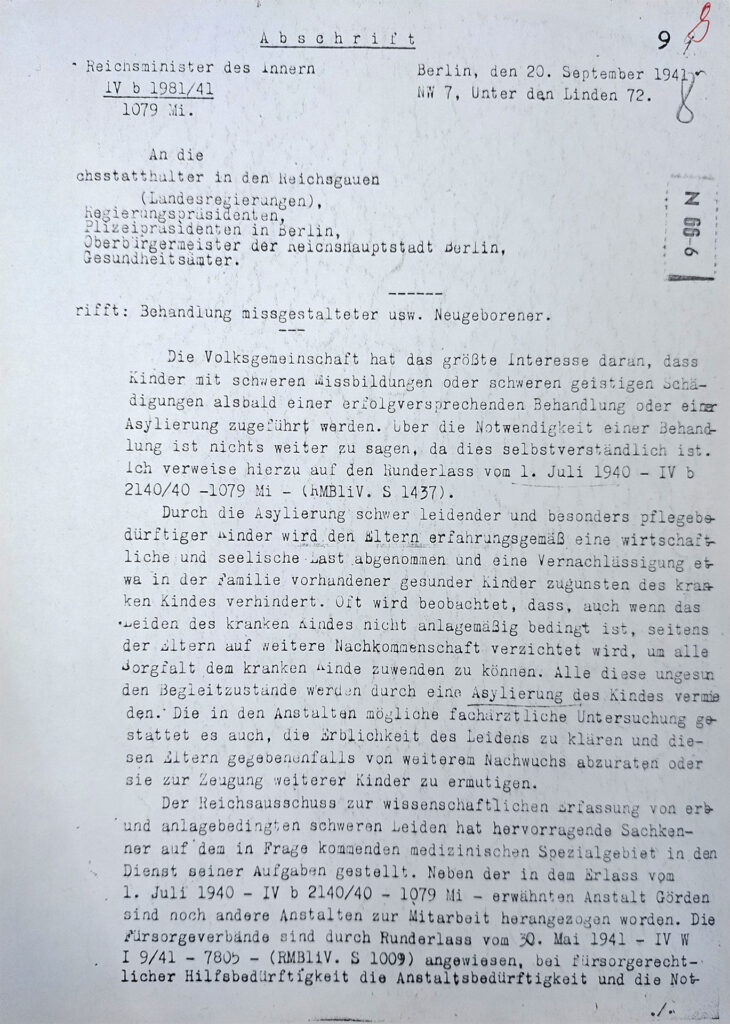

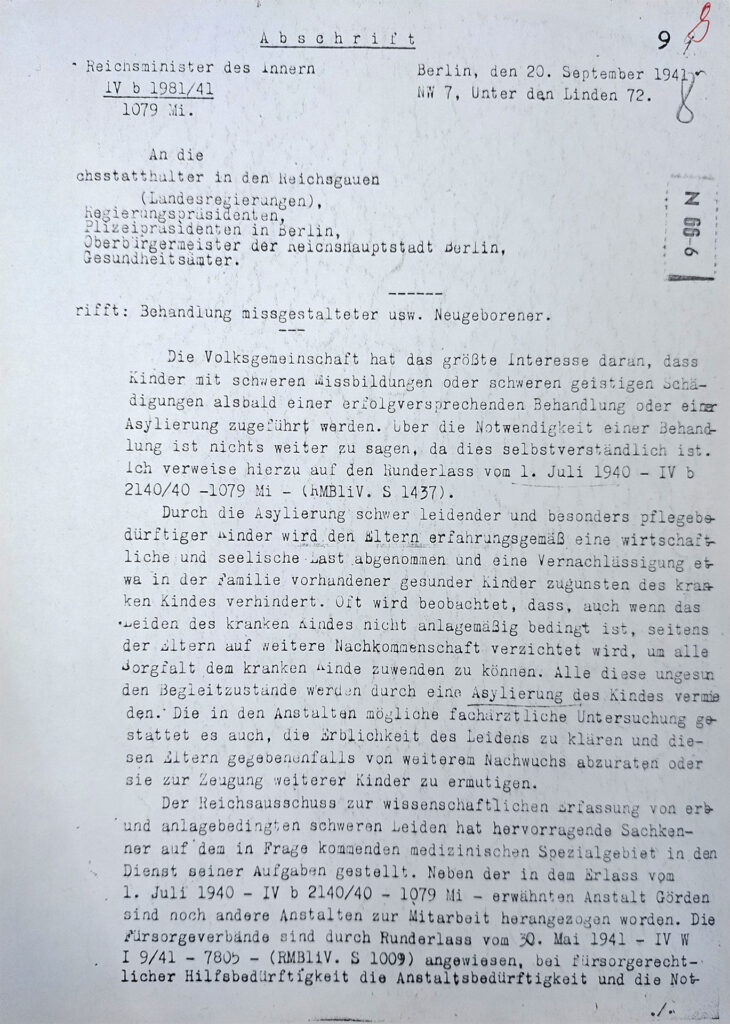

Bescheinigung des Todes vom 13.9.1941.

Staatsarchiv Hamburg 352-8/7 Staatskrankenanstalt Langenhorn Nr. 86294.

Vor der »Kinderfachabteilung« Lüneburg wurden mindestens zehn Kinder aus dem späteren Einzugsgebiet in den beiden Hamburger »Kinderfachabteilungen« Rothenburgsort (1) und Langenhorn (9) aufgenommen:

- Hermann Beekhuis (Leer)

- Helmuth Beneke (Bremervörde)

- Gerda Cordes (Uelzen)

- Marianne Harms (Bardowick)

- Hillene Hellmers (Leer)

- Irmgard Jagemann (Bremen)

- Rosemarie Kablitz (Wilstedt)

- Edda Purwin (Lüneburg)

- Günther Schindler (Wilhelmshaven)

- Hans-Ludwig Würflinger (Bremen)

Fünf kamen zwischen 1942 und 1943 wieder nach Hause, die anderen wurden ermordet. Das jüngste Opfer war Hermann Beekhuis. Er wurde im Alter von dreieinhalb Monaten im Kinderkrankenhaus Rothenburgsort ermordet. Das offizielle Sterbedatum ist gefälscht.

Am Anfang von der Nazi-Zeit gibt es noch keine Kinder-Fachabteilung in Lüneburg.

Darum kommen 10 Kinder aus Lüneburg

in Kinder-Fachabteilungen nach Hamburg.

In Hamburg gibt es 2 Kinder-Fachabteilungen:

Rothenburgsort und Langenhorn.

Die 10 Kinder aus Lüneburg heißen:

• Hermann Beekhuis

• Helmut Beneke

• Gerda Cordes

• Marianne Harms

• Hillene Hellmers

• Irmgard Jagemann

• Rosemarie Kablitz

• Edda Purwin

• Günther Schindler

• Hans-Ludwig Würflinger

5 von diesen 10 Kinder kommen

wieder nach Hause.

Die anderen 5 Kinder werden ermordet.

Hermann Beekhuis ist das jüngste Kind.

Er ist erst 3,5 Monate alt.

Hermann stirbt in Rothenburgsort.

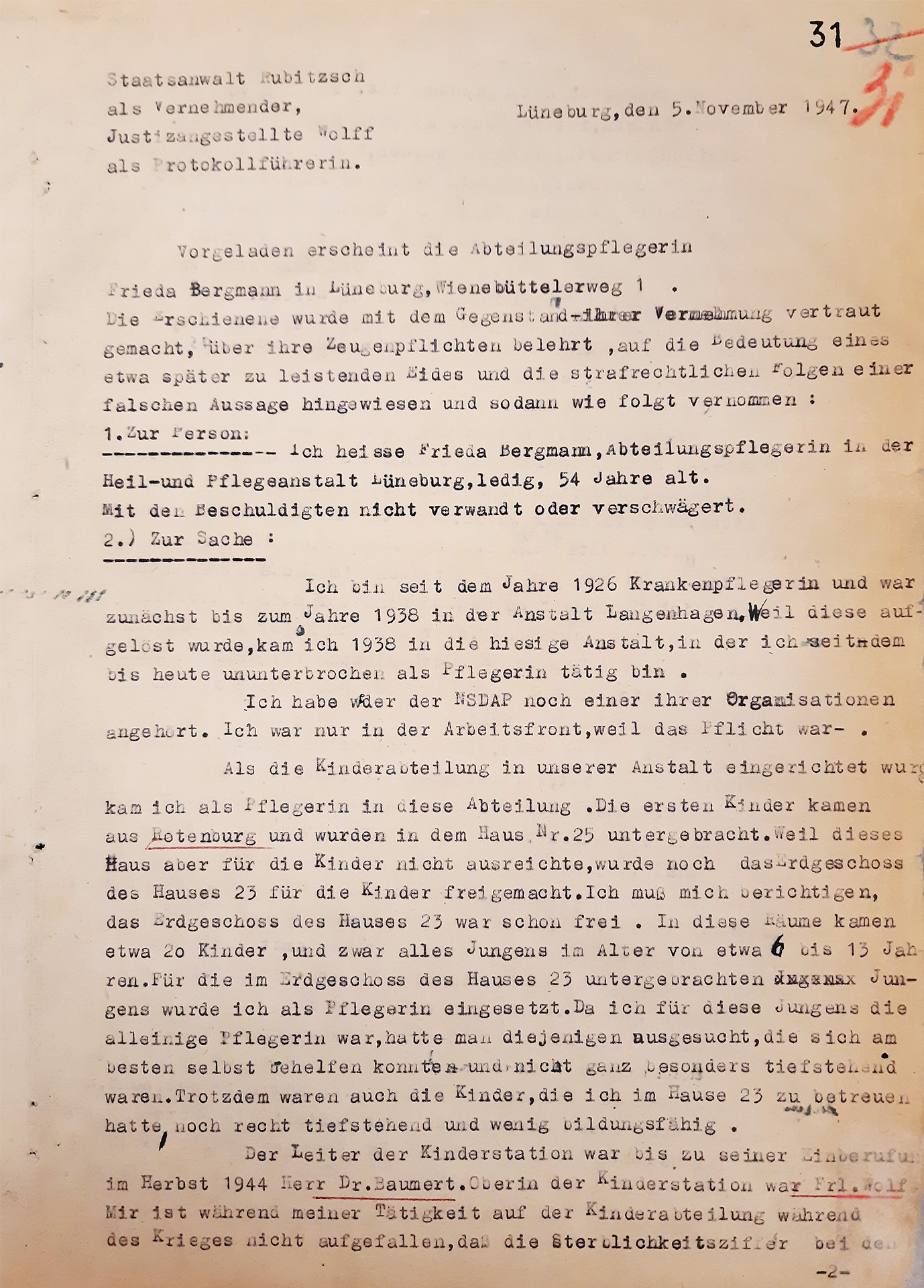

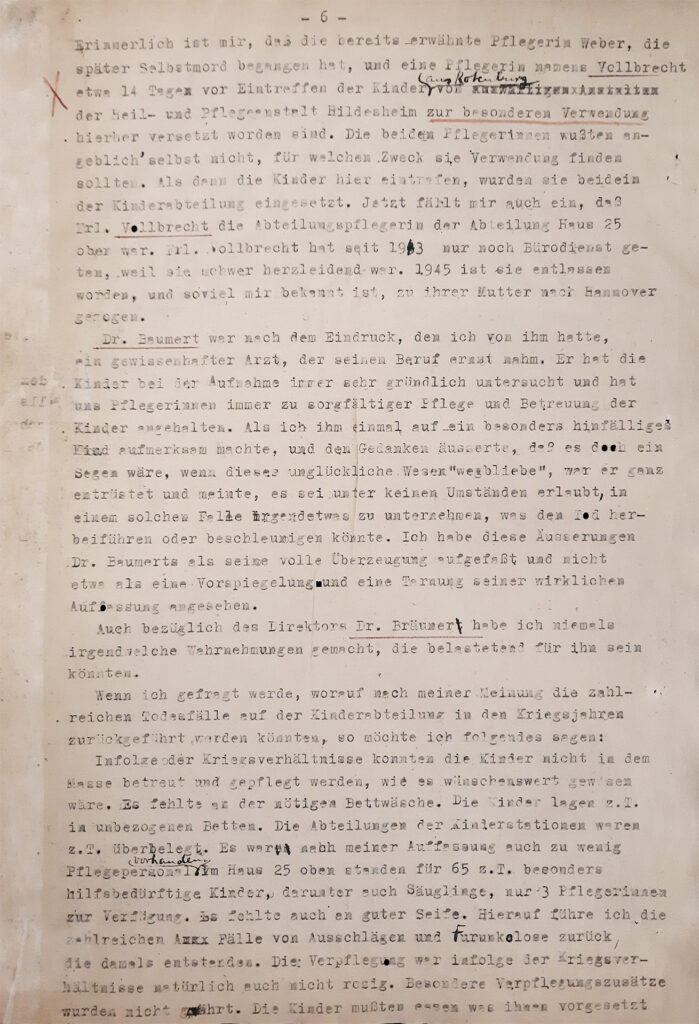

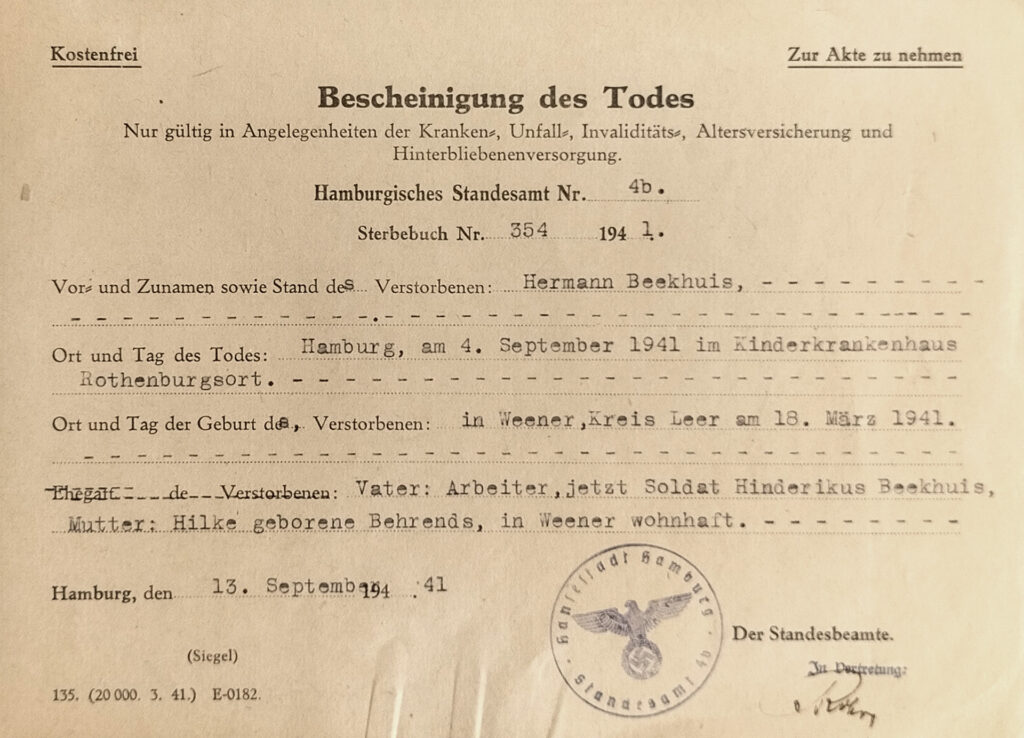

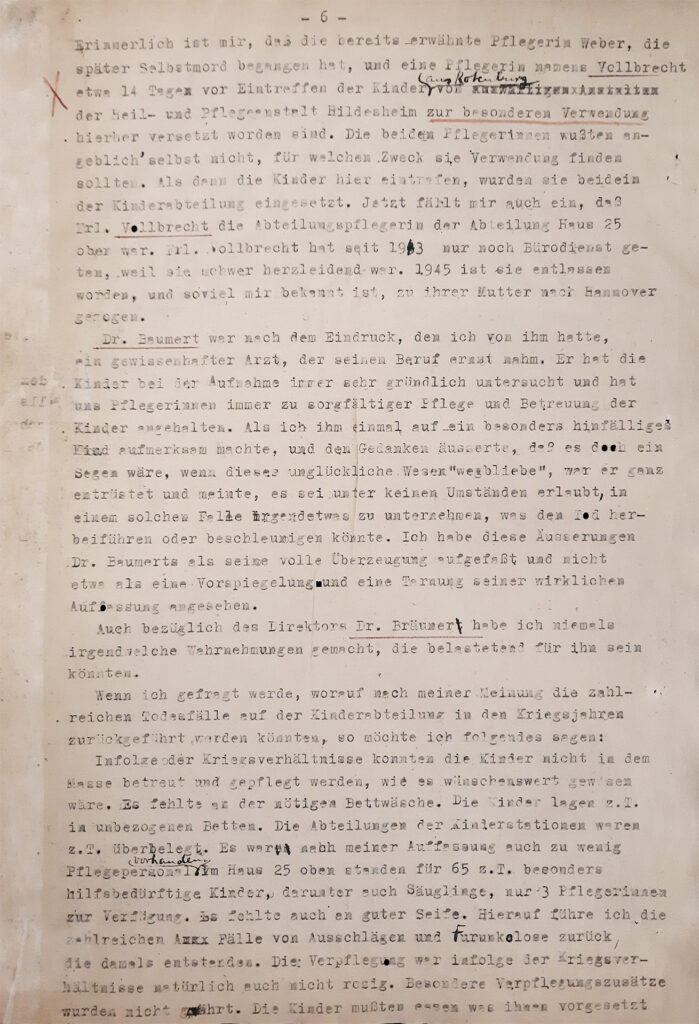

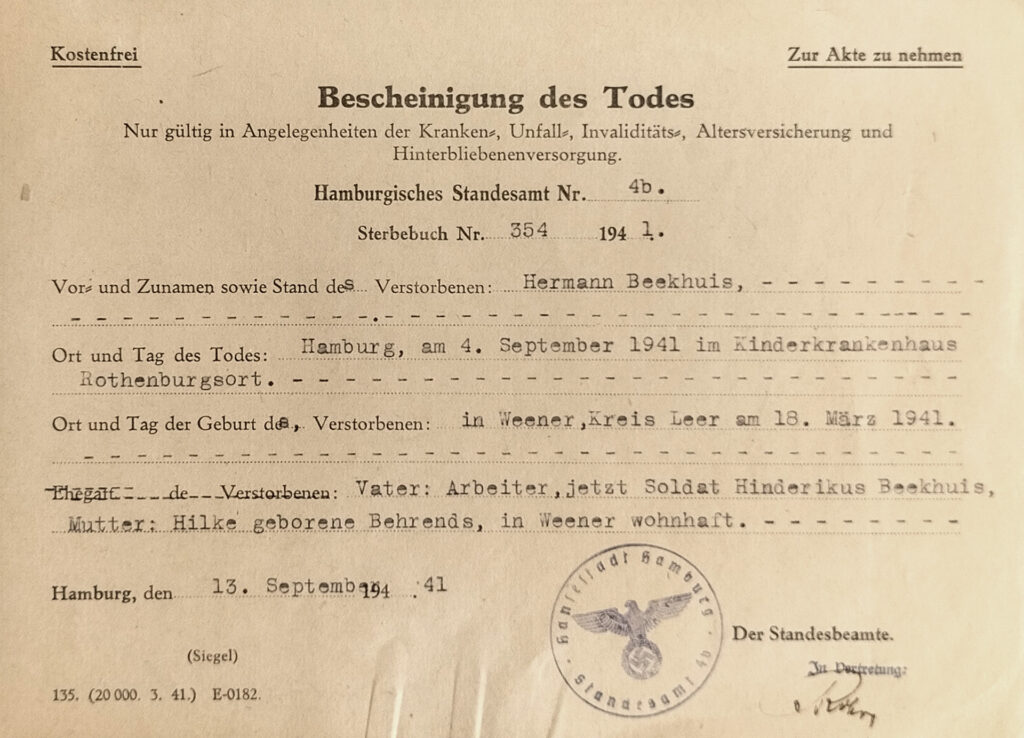

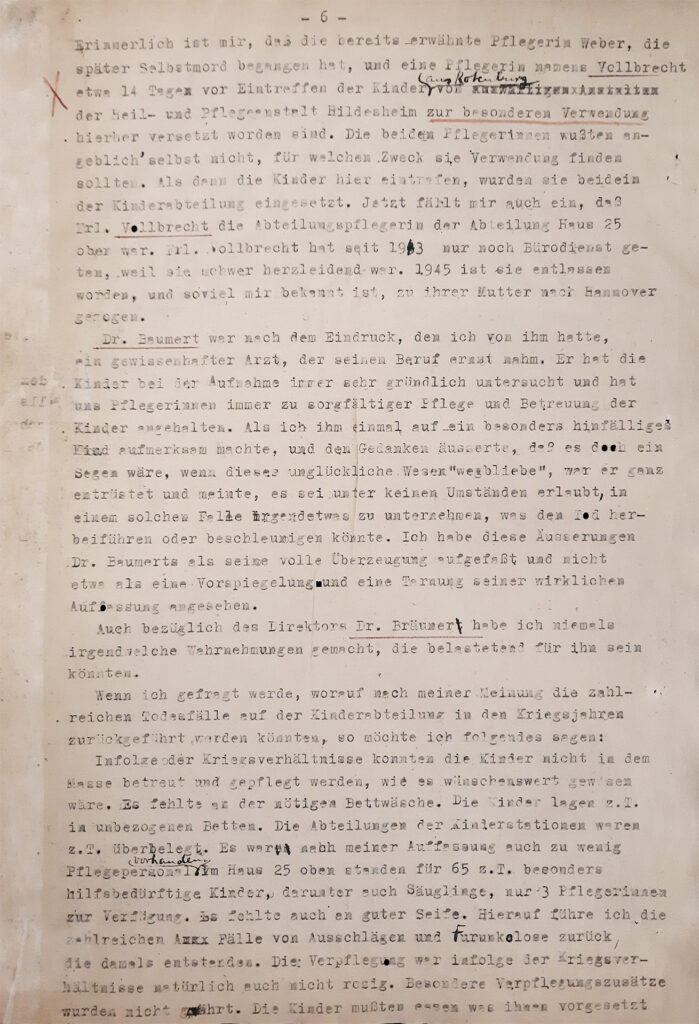

Auszug aus der Vernehmung von Frieda Bergmann vom 5.11.1947.

NLA Hannover Nds. 721 Lüneburg Acc. 8/98 Nr. 3.

Am 9. und 10. Oktober 1941 wurden 138 Kinder und Jugendliche in die »Kinderfachabteilung« in Haus 25 und Haus 23 der Heil- und Pflegeanstalt Lüneburg aufgenommen. Sie kamen aus den Rotenburger Anstalten der Inneren Mission. Nur neun Jungen und sieben Mädchen dieser ersten Gruppe überlebten. Frieda Bergmann, Pflegerin in der Lüneburger »Kinderfachabteilung«, wurde nach dem Krieg zur Anfangszeit in Lüneburg befragt.

In der Anstalt in Lüneburg gibt es

eine Kinder-Fachabteilung.

Die Kinder-Fachabteilung ist

in den Häusern 23 und 25.

Dort werden Kinder mit Behinderungen ermordet.

Die ersten Kinder kommen am 9. und 10. Oktober 1941 in die Kinder-Fachabteilung.

Es sind 138 Kinder.

Sie kommen aus der Anstalt in Rotenburg.

Nur wenige Kinder aus Rotenburg überleben

in Lüneburg:

9 Jungen und 7 Mädchen.

Frieda Bergmann ist Pflegerin in der Anstalt

in Lüneburg.

Sie arbeitet in der Kinder-Fachabteilung.

Nach der Nazi-Zeit fragt man Frieda Bergmann wie es in der Kinder-Fachabteilung war.

Ihre Antworten stehen in diesem Protokoll aus dem Jahr 1947.

Sie sagt:

Es sind Kinder gestorben.

Aber nicht viel mehr als sonst.

Es gab keine Morde.

Alle gestorbenen Kinder waren wirklich tot-krank.

Die Pflegerin hat ihre Arbeit gut gemacht.

Der Arzt hat seine Arbeit auch gut gemacht.

Luftbild der Rotenburger Anstalten der Inneren Mission, Postkarte, vor 1945.

ArEGL 99.

Die Rotenburger Anstalten der Inneren Mission sollten als Hilfskrankenhaus für Bremer Opfer des Luftkrieges genutzt werden. Dafür wurde die Kinderstation geschlossen und die dort behandelten Kinder wurden aufgeteilt. 99 Kinder kamen in die von Bodelschwinghschen Anstalten Bethel in Bielefeld, 24 Kinder kamen nach Lemgo in die Stiftung Eben-Ezer. Die nicht beschulbaren Kinder wurden in die Lüneburger »Kinderfachabteilung« verlegt.

In Rotenburg gibt es eine Anstalt:

Rotenburger Anstalten.

Im Zweiten Weltkrieg gibt es viele Verletzte.

Darum braucht man viele Plätze

in Krankenhäusern.

Man braucht auch die Plätze

von den Rotenburger Anstalten.

Darum schließt man die Kinder-Station

von den Rotenburger Anstalten.

Die Kinder müssen umziehen.

Einige Kinder kommen nach Bethel.

Ein paar Kinder kommen nach Lemgo

in die Stiftung Eben-Ezer.

Einige Kinder aus Rotenburg kommen auch

in die Anstalt nach Lüneburg.

Die Ärzte sagen,

diese Kinder können nicht entwickeln.

Darum kommen sie in die Kinder-Fachabteilung.

Sie sollen dort ermordet werden.

Für viele Kinder und Jugendliche mit Beeinträchtigungen aus der Provinz Hannover waren die Rotenburger Anstalten der Inneren Mission ein großes Heim. Auf den hier abgebildeten Fotos sind mit Sicherheit auch Kinder und Jugendliche zu sehen, die später in Lüneburg ermordet wurden. Auf dem Bild der Jungen vor dem Wichernhaus ist zum Beispiel links Eckart Willumeit aus Celle zu erkennen.

In den Rotenburger Anstalten waren

viele Kinder mit Behinderungen.

Die Kinder kamen aus verschiedenen Orten

nach Rotenburg.

Das ist ein Foto von Kindern

in den Rotenburger Anstalten.

Einige von den Kindern kommen später

in die Anstalt nach Lüneburg.

Dort werden sie

in der Kinder-Fachabteilung ermordet.

Zum Beispiel: Eckart Willumeit.

Er ist links unten auf dem Foto.

Jugendliche mit Bruder Karl Stallbaum vor dem Wichernhaus der Rotenburger Werke der Inneren Mission, etwa 1938. Fotograf Kurt Stallbaum.

Archiv Rotenburger Werke der Inneren Mission.

Gruppenbild vom Kinder-Transport aus Hannover-Langenhagen. Links im Bild steht der Rotenburger Direktor, Pastor Johannes Buhrfeind. Rechts hinter ihm steht der Abteilungspfleger oder »Hausvater« Grützmacher.

Archiv Rotenburger Werke der Inneren Mission.

Unter den Kindern, die nach Lüneburg verlegt wurden, befanden sich auch 25, die am 18. März 1938 aus der Nervenheilanstalt Hannover-Langenhagen nach Rotenburg umgezogen waren, nachdem die Kinderklinik in Langenhagen geschlossen worden war. Dazu gehörten neben Eckart Willumeit auch Friedrich Daps, Waldemar Borcholte und Hans-Herbert Niehoff. Sie müssen vier der Kinder auf dem Foto sein.

Auch in Langenhagen gibt es eine Kinder-Station.

Die Kinder-Station wird geschlossen.

Die Kinder aus Langenhagen kommen

in die Rotenburger Anstalt.

Das ist am 18. März 1938.

25 Kinder aus Langenhagen kommen später

in die Anstalt nach Lüneburg.

Zum Beispiel:

• Eckart Willumeit

• Friedrich Daps

• Waldemar Borcholte

• Hans-Herbert Niehoff

Auf diesem Foto sind die 4 Kinder

aus Langenhagen.

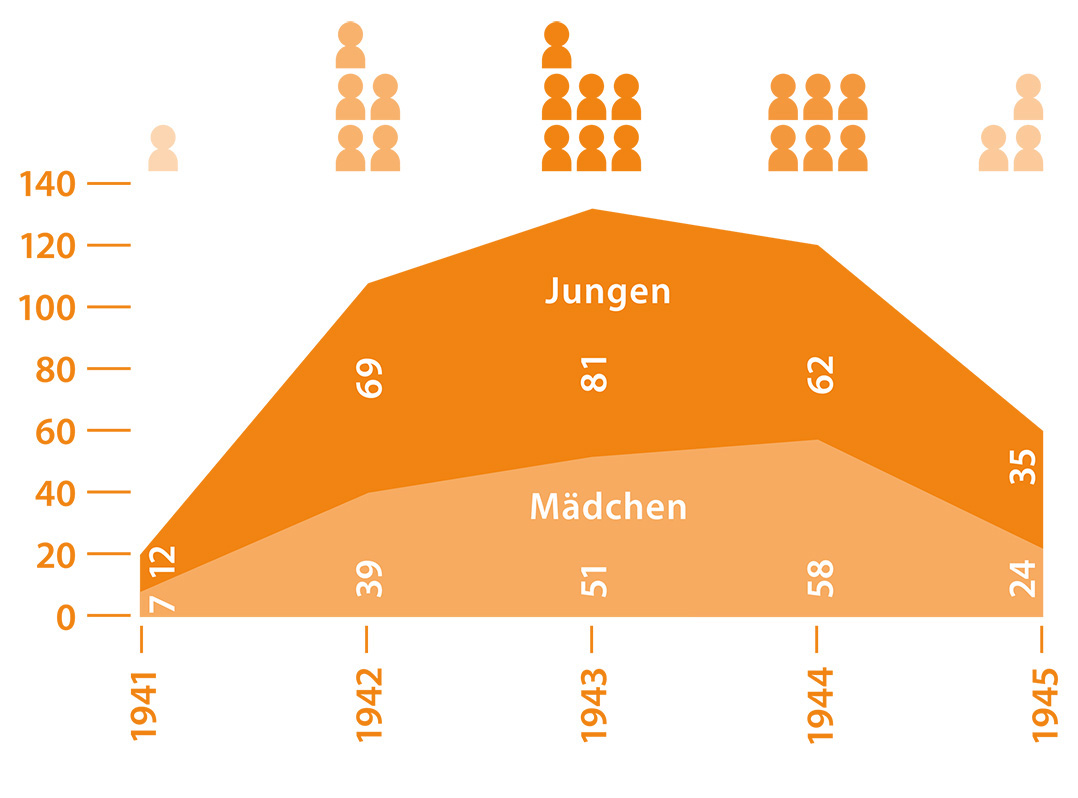

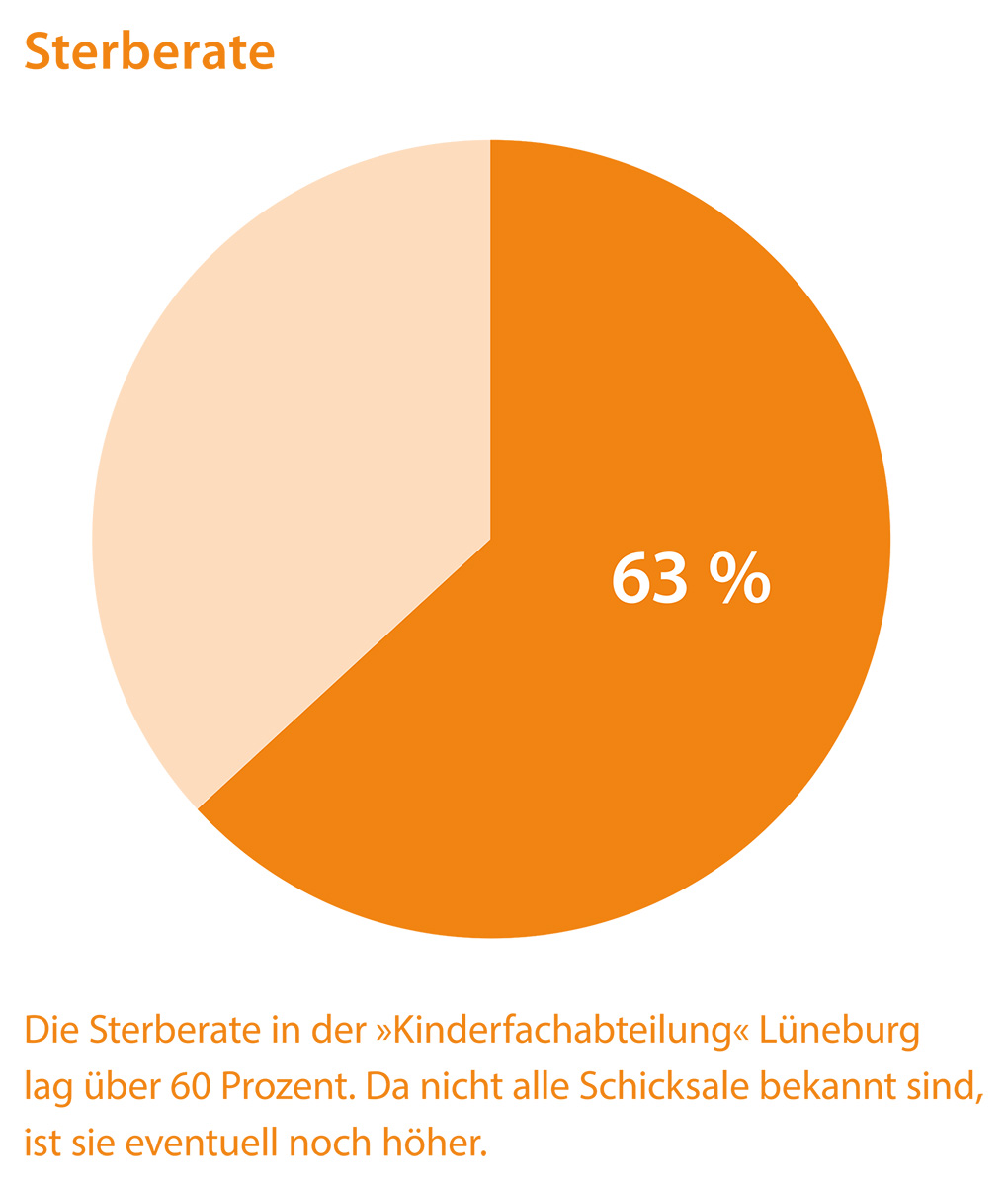

Insgesamt wurden von 1941 bis 24. August 1945 mindestens 762 Kinder und Jugendliche im Alter von einem Tag bis 16 Jahren in die »Kinderfachabteilung« Lüneburg eingewiesen. Über 440 von ihnen überlebten den Aufenthalt nicht. Bei weiteren 61 Kindern und Jugendlichen ist unklar, ob sie überlebten.

Die Kinder-Fachabteilung in Lüneburg gibt es

in den Jahren 1941 bis 1945.

In dieser Zeit sind etwa 762 Kinder dort.

Die Kinder sind zwischen einem Tag

und 16 Jahre alt.

Mehr als 440 Kinder sterben

in der Kinder-Fachabteilung in Lüneburg.

Bei 61 Kindern wissen wir heute nicht,

was mit ihnen passiert ist.

Wir wissen nicht,

ob sie überlebt haben oder nicht.

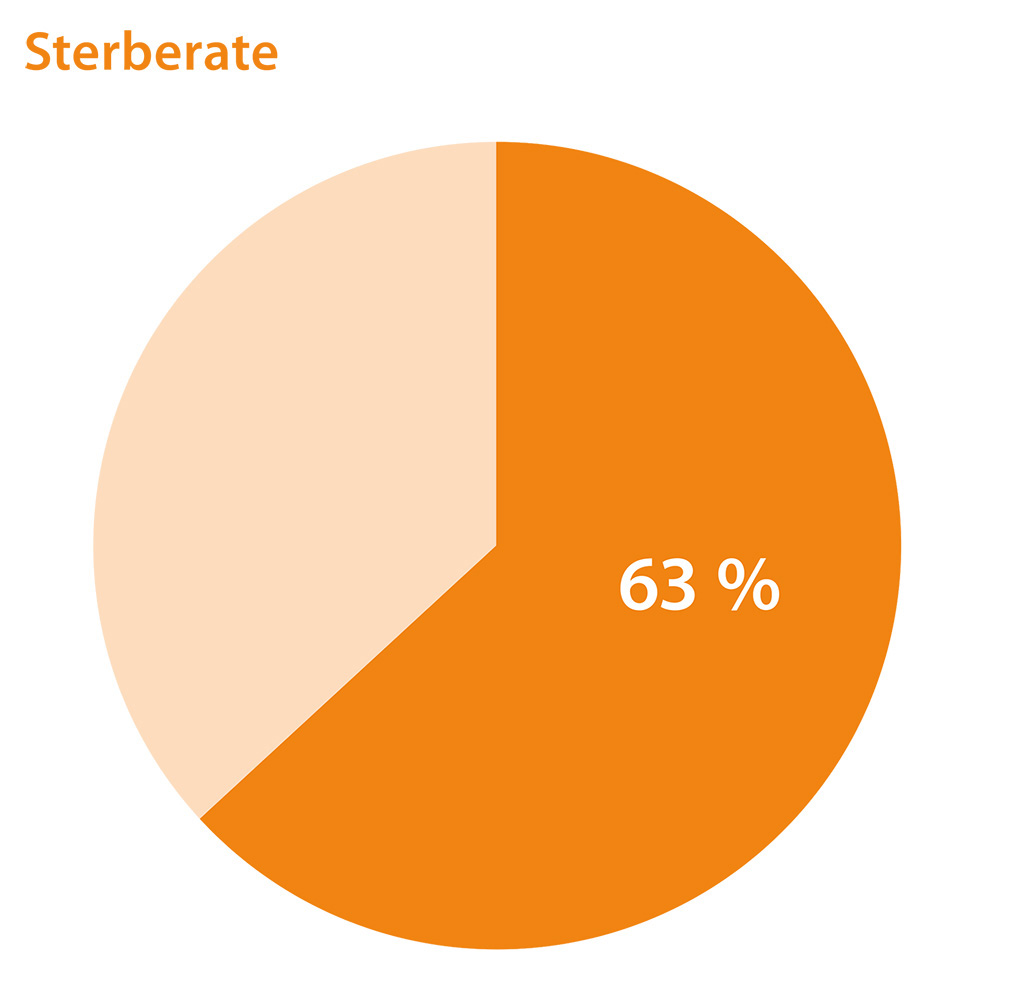

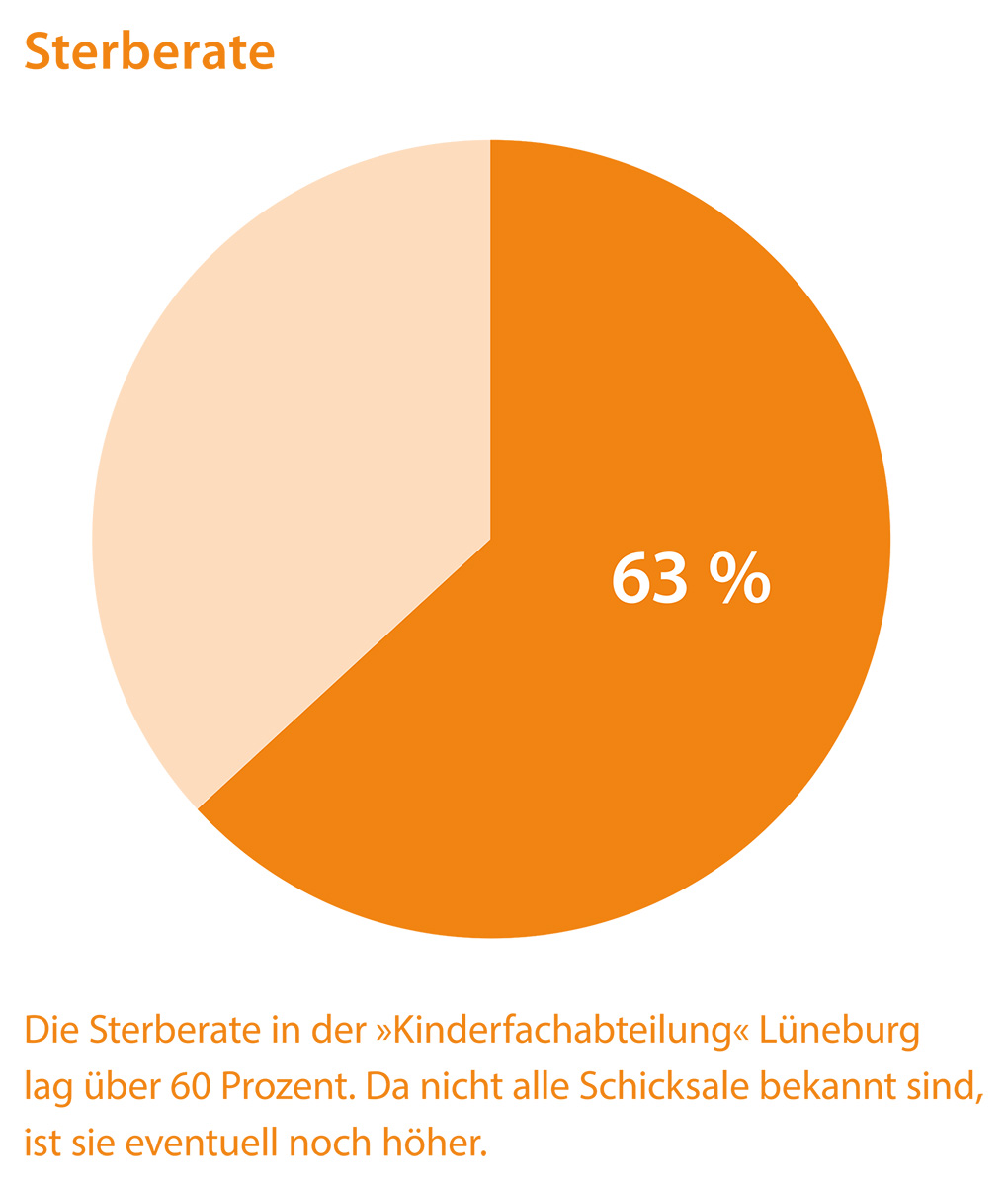

Die Sterberate in der »Kinderfachabteilung« Lüneburg lag über 60 Prozent. Da nicht alle Schicksale bekannt sind, ist sie eventuell noch höher.

Mehr als die Hälfte von den Kinder

in der Kinder-Fachabteilung in Lüneburg sterben.

Wir wissen heute nicht alles:

Vielleicht sind noch mehr Kinder gestorben.

Wir wissen nicht über alle Kinder Bescheid.

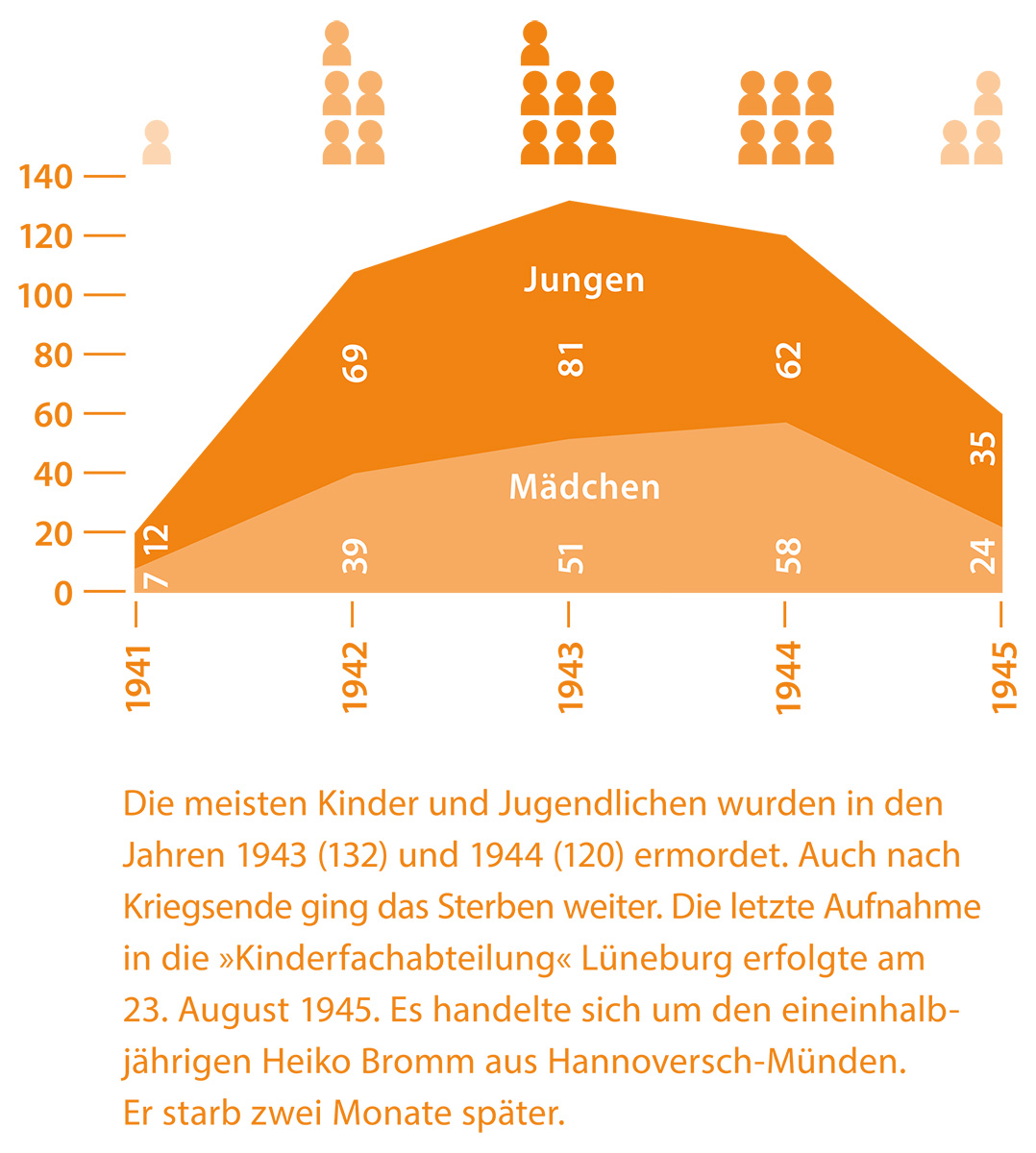

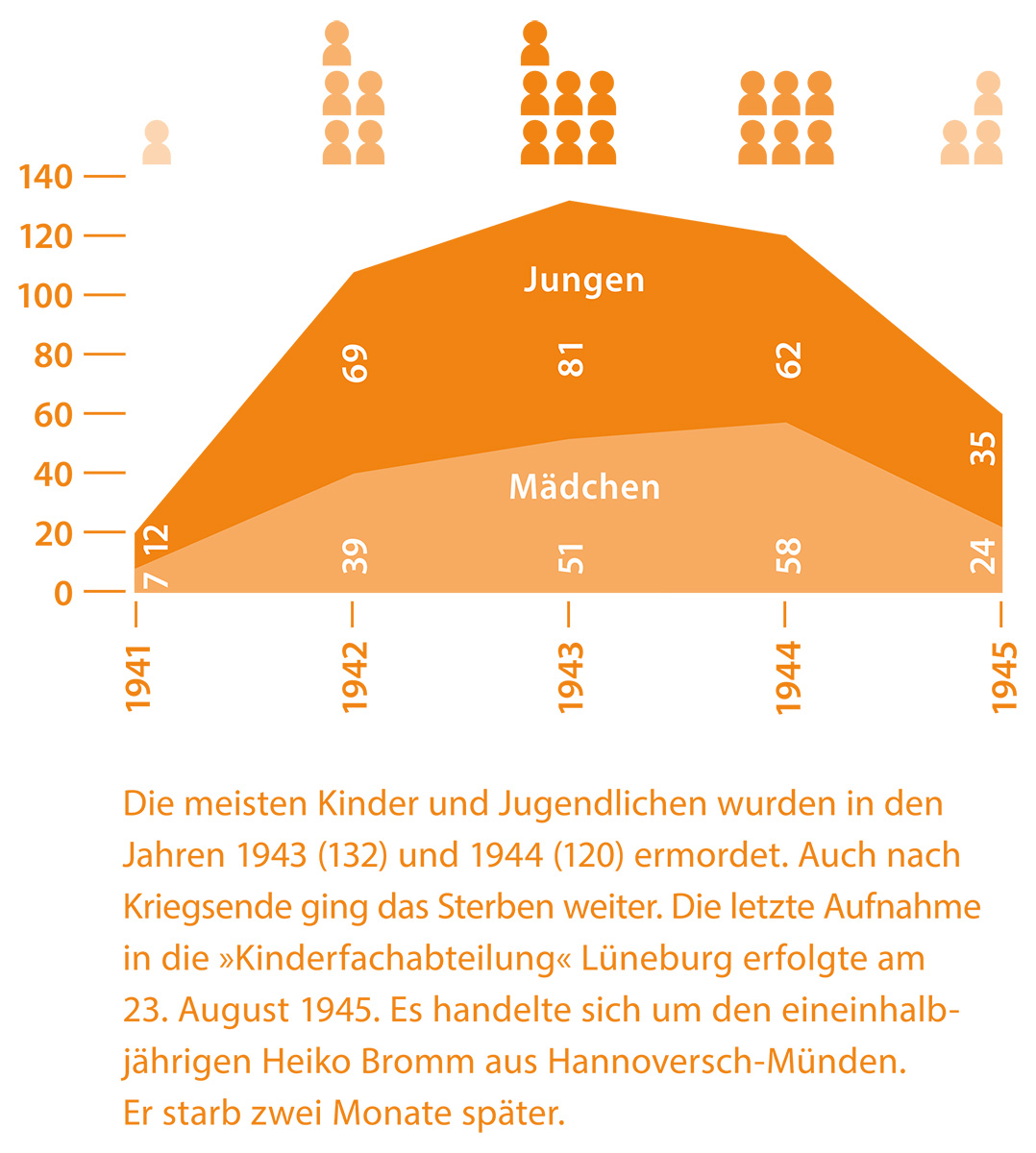

Die meisten Kinder und Jugendlichen wurden in den Jahren 1943 (132) und 1944 (120) ermordet. Auch nach Kriegsende ging das Sterben weiter. Die letzte Aufnahme in die »Kinderfachabteilung« Lüneburg erfolgte am 23. August 1945. Es handelte sich um den eineinhalbjährigen Heiko Bromm aus Hannoversch-Münden. Er starb zwei Monate später.

Die meisten Kinder werden in diesen Jahren getötet:

• Im Jahr 1943 werden 132 Kinder ermordet.

• Im Jahr 1944 werden 120 Kinder ermordet.

Dann ist der Zweite Weltkrieg zu Ende.

Aber es werden immer noch Kinder ermordet.

Am 23. August 1945 kommt das letzte Kind

in die Kinder-Fachabteilung in Lüneburg.

Das Kind ist 8 Jahre alt.

Es heißt Heiko Bromm.

Er kommt aus Hannoversch-Münden.

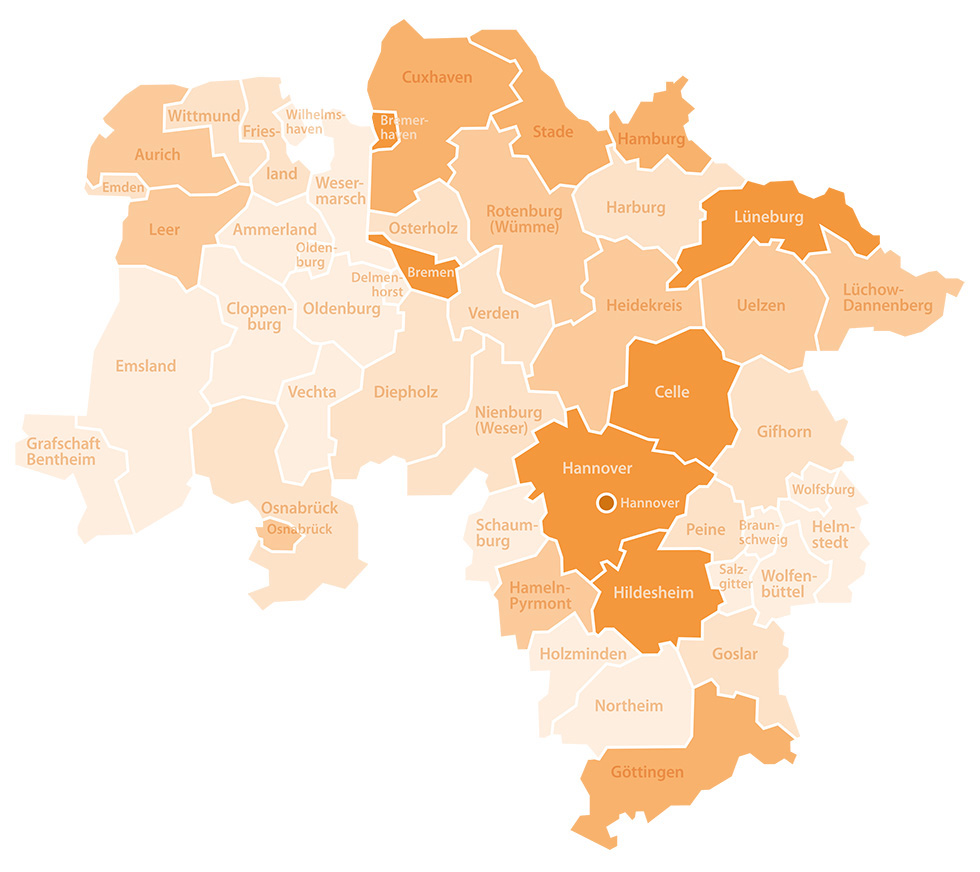

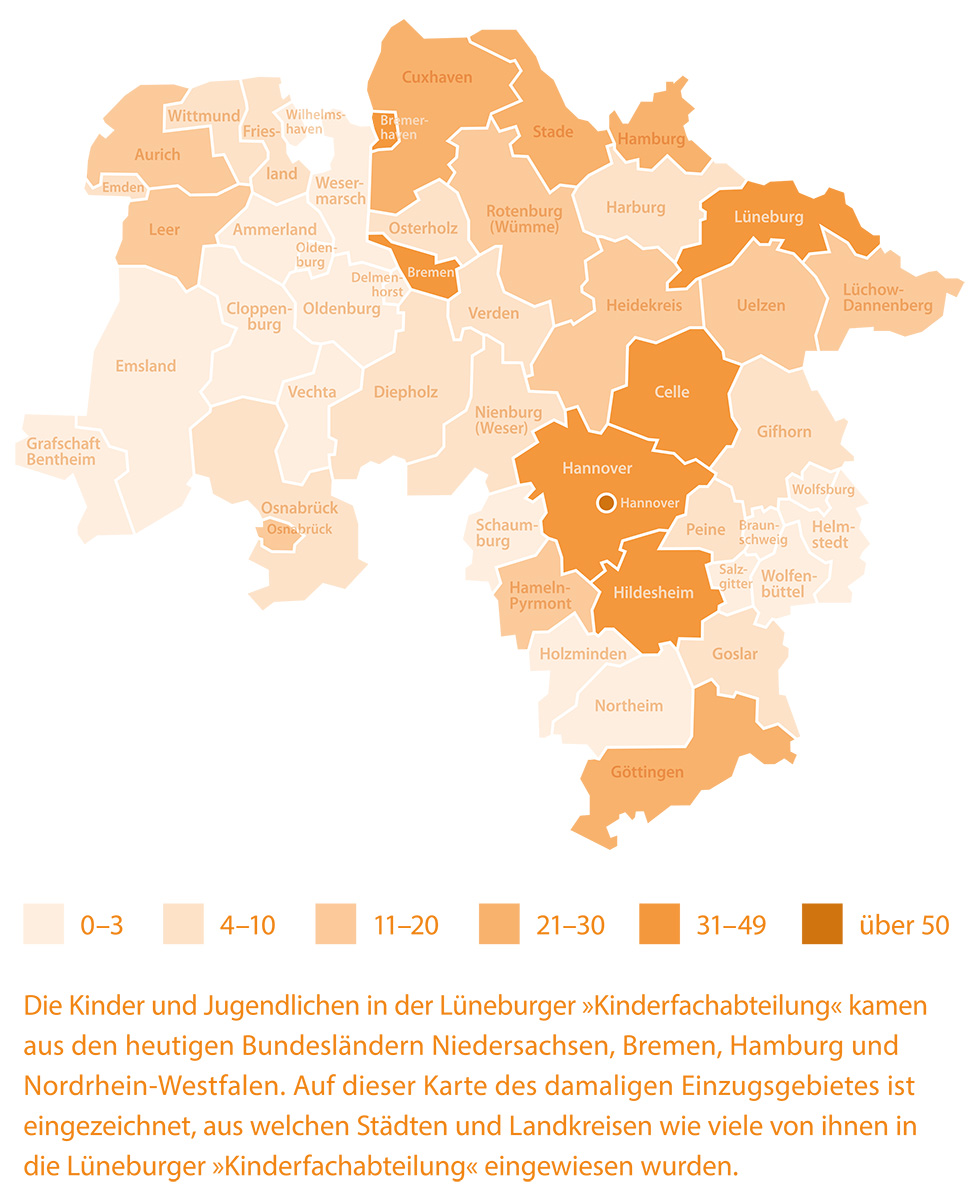

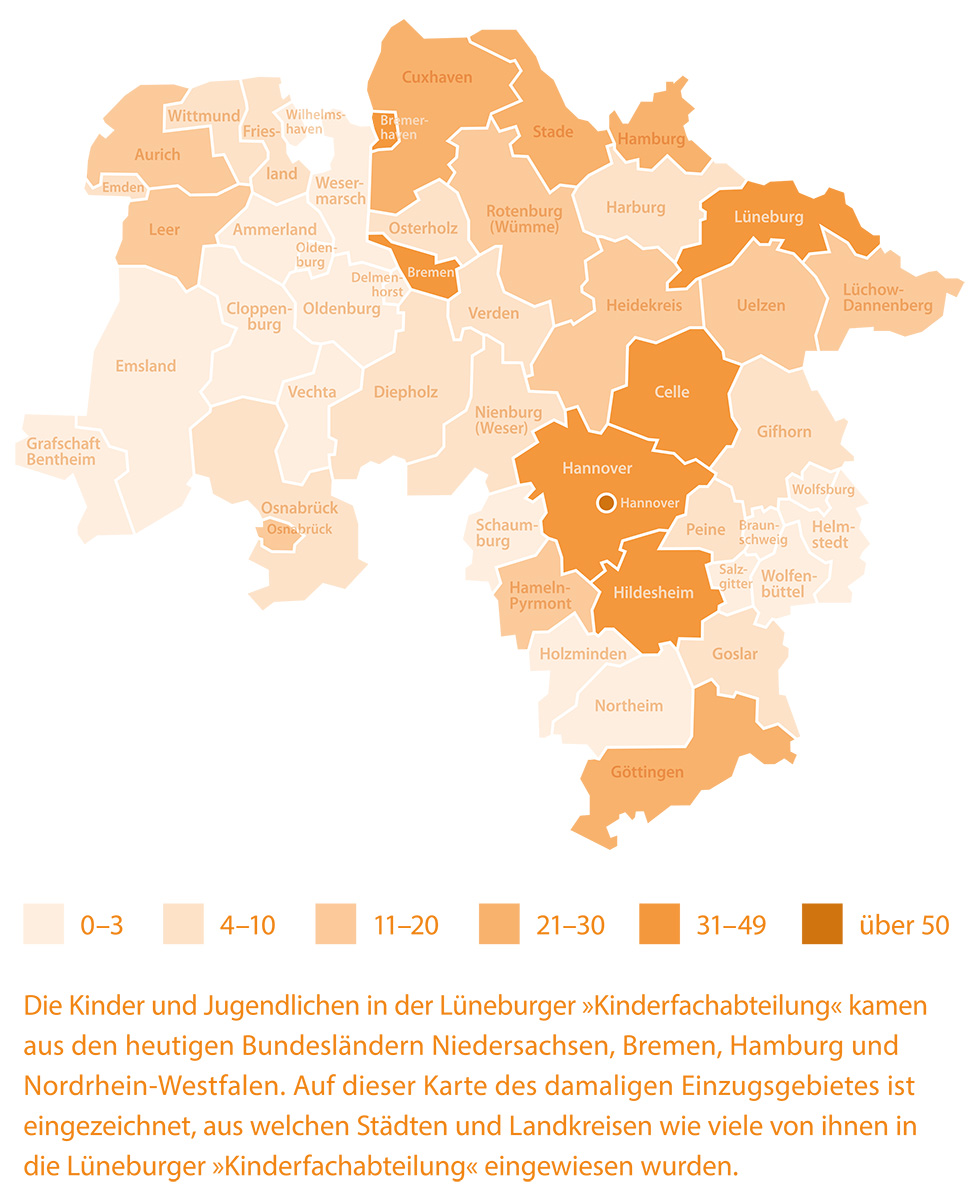

Ob und wie viele Kinder und Jugendliche in eine »Kinderfachabteilung« eingewiesen wurden, hing vom Handeln der Eltern, Hebammen, Lehrkräfte und Gesundheitsämter ab. Diese handelten regional sehr unterschiedlich. Es gab Regionen, aus denen kein oder nur ein einziges Kind gemeldet und eingewiesen wurde (zum Beispiel Cloppenburg und Vechta). Aus Hannover (135), Bremen (39), Celle (33), Lüneburg (33), Bremerhaven (31) und Hildesheim (31) kamen auffällig viele Kinder in die »Kinderfachabteilung«.

Es gibt viele Kinder in der Kinder-Fachabteilung

in Lüneburg.

Es sind Kinder mit Behinderungen und

Kinder mit Krankheiten.

Die Kinder kommen aus verschiedenen Orten nach Lüneburg.

Aus einigen Orten kommen viele Kinder nach Lüneburg:

• Etwa 130 Kinder kommen aus Hannover.

• Etwa 48 Kinder kommen aus Ostfriesland.

• Etwa 39 Kinder kommen aus Bremen.

• Etwa 31 Kinder kommen aus Bremerhaven.

Aus einigen Orten kommen nur wenige Kinder nach Lüneburg.

Zum Beispiel:

Aus dem Emsland kommt nur ein Kind.

Diese Menschen entscheiden,

ob ein Kind in die Kinder-Fachabteilung kommt:

• Eltern.

• Hebammen.

• Lehrer.

• Mitarbeiter von Gesundheits-Ämtern.

Die Menschen entscheiden unterschiedlich.

Die Kinder und Jugendlichen in der Lüneburger »Kinderfachabteilung« kamen aus den heutigen Bundesländern Niedersachsen, Bremen, Hamburg und Nordrhein-Westfalen. Auf dieser Karte des damaligen Einzugsgebietes ist eingezeichnet, aus welchen Städten und Landkreisen wie viele von ihnen in die Lüneburger »Kinderfachabteilung« eingewiesen wurden.

Auf dieser Karte sieht man Städte und Landkreise.

Aus diesen Städten und Landkreisen

kommen Kinder in die Anstalt nach Lüneburg.

Die Kinder kommen in die Kinder-Fachabteilung.

Die Zahlen auf der Karte zeigen, wie viele Kinder aus einer Stadt nach Lüneburg kommen.

Einige Städte und Landkreise fehlen auf der Karte.

Das heißt:

Aus diesen Städten und Landkreisen kommen keine Kinder in die Anstalt nach Lüneburg.

Dort gibt es bestimmt auch Kinder

mit Behinderungen und Erkrankungen.

Aber keiner meldet diese Kinder beim Amt.

Darum kommen diese Kinder nicht

in die Kinder-Fachabteilung.

Diese Kinder haben großes Glück.

Herta Ley, etwa Frühjahr 1932.

ArEGL.

Im Gesundheitsamt Leer gab es eifrige Mitarbeiterinnen und Mitarbeiter. Von 13 Kindern aus Leer wurden acht ermordet. Unter ihnen auch Herta Ley aus Westrhauderfehn. Sie kam am 9. Oktober 1941 nach Lüneburg und gehört zu den ersten Kindern, die ermordet wurden.

Das Gesundheits-Amt in Leer meldet

besonders viele Kinder.

Es meldet 13 Kinder.

8 von diesen Kinder werden ermordet.

Auch Hertha Ley wird ermordet.

Sie kommt aus Westrhauderfehn

bei Leer.

Sie kommt am 9. Oktober 1941

in die Kinder-Fachabteilung in Lüneburg.

Herta Ley wird ermordet.

Das ist ein Foto von Hertha Ley

aus dem Frühjahr 1932.

Jugendliche, die sich nicht angepasst verhielten und als »nicht erziehungsfähig« galten, wurden von der Jugendfürsorge für eine Aufnahme in eine »Kinderfachabteilung« gemeldet. Als Arzt der Jugendfürsorgeanstalt Wunstorf wies Willi Baumert seine Schützlinge persönlich in die Lüneburger »Kinderfachabteilung« ein. Das musste auch Siegfried Eilers erleben, der gemeinsam mit drei Geschwistern nach Lüneburg kam. Sein jüngerer Bruder Ernst überlebte den Aufenthalt nicht.

Auch Jugendliche kommen

in die Kinder-Fachabteilung.

Das Jugendamt meldet zum Beispiel Jugendliche,

• die sich schlecht benehmen.

• sich anders verhalten, als die Nazis es wollen.

Das Jugendamt sagt:

Man kann diese Jugendlichen nicht erziehen.

Darum müssen sie

in die Kinder-Fachabteilung nach Lüneburg.

Willi Baumert ist Chef

von der Kinder-Fachabteilung.

Und er ist Arzt in einem Jugendheim

in Wunstorf.

Willi Baumert schickt Jugendliche aus Wunstorf

in die Kinder-Fachabteilung nach Lüneburg.

Er entscheidet allein,

welche Jugendliche nach Lüneburg kommen.

Siegfried Eilers ist ein Jugendlicher

aus dem Jugendheim in Wunstorf.

Er hat 3 Geschwister.

Sie alle kommen in die Kinder-Fachabteilung

nach Lüneburg.

Der kleine Bruder von Siegfried wird ermordet.

Ernst Eilers im Arm seines Vaters Wilhelm Eilers, links neben ihm steht seine Schwester Hannelore, Brünninghausen, etwa 1941.

Privatbesitz Susanne Grünert.

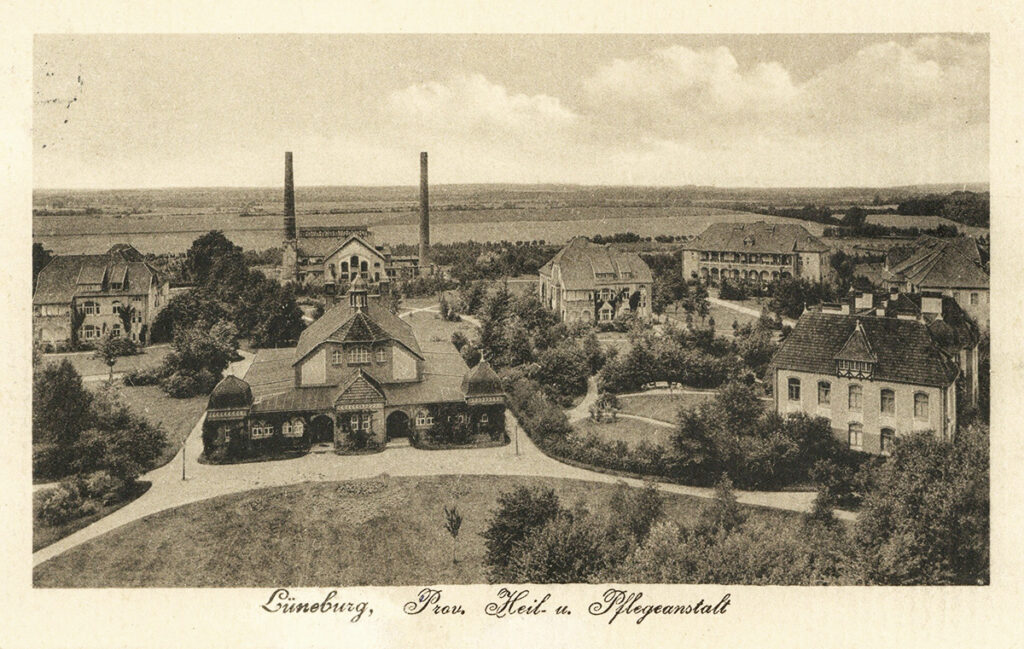

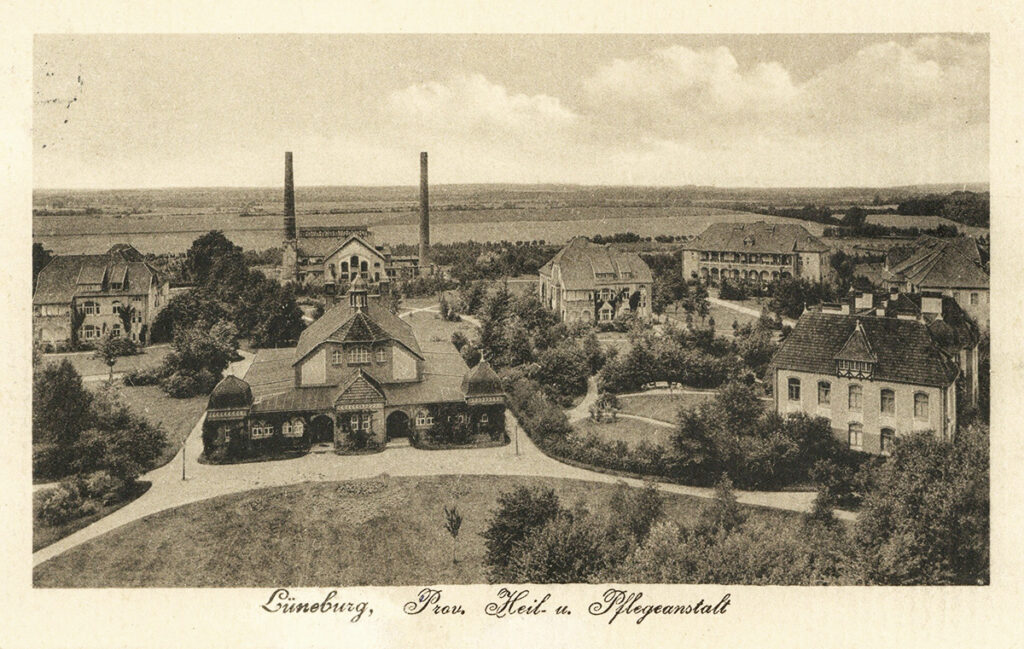

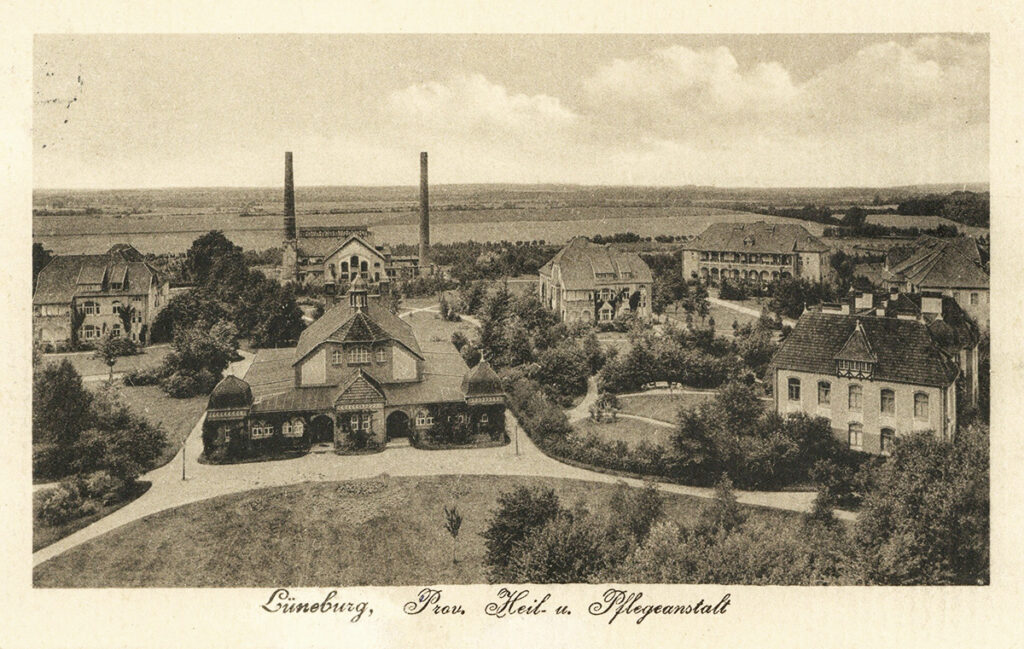

Postkarte der Heil- und Pflegeanstalt Lüneburg, 1915.

ArEGL 99.

Die Postkarte zeigt die Heil- und Pflegeanstalt Lüneburg, im Vordergrund das Gesellschaftshaus (Haus 36). Im Hintergrund sind die Häuser 24, 23 und 25 (von links nach rechts) zu sehen, in denen die »Kinderfachabteilung« Lüneburg untergebracht war. Es gibt mindestens 13 verschiedene Postkarten mit unterschiedlichen Motiven und Ansichten des Geländes und einzelner Gebäude. Nur auf dieser Karte sind alle Gebäude der »Kinderfachabteilung« abgebildet.

Das ist eine Postkarte

von der Anstalt in Lüneburg.

Man sieht vorne auf der Postkarte

das Gesellschafts-Haus.

Das ist Haus Nummer 36.

Hinten dem Gesellschafts-Haus ist

die Kinder-Fachabteilung.

Das sind die Häuser Nummer 23, 24 und 25.

Es gibt viele Postkarten von der Anstalt

in Lüneburg.

Man sieht auf den Postkarten

die verschiedenen Häuser von der Anstalt.

Diese Postkarte ist besonders.

Denn auf dieser Postkarte ist

die ganze Kinder-Fachabteilung.

Im Obergeschoss von Haus 25 waren die Mädchen, im Erdgeschoss die Jungen untergebracht. Im Erdgeschoss von Haus 23 wurden weitere 20 Jungen untergebracht. Im Herbst 1944 zog die »Kinderfachabteilung« aus Haus 23 aus. Die Jungen wurden nach Haus 25 verlegt. Haus 25 wurde ab Anfang 1945 als Lazarett genutzt. Die »Kinderfachabteilung« zog in das Haus 24 und blieb dort bis 1946.

Die Kinder-Fachabteilung von der Anstalt

in Lüneburg ist in Haus 25.

Oben im Haus wohnen die Mädchen.

Unten im Haus wohnen die Jungen.

Auch unten im Haus 23 wohnen 20 Jungen.

Im Herbst 1944 zieht die Kinder-Fachabteilung aus Haus 23 aus.

Die Jungen kommen dann in Haus 25.

Anfang 1945 zieht die Kinder-Fachabteilung

in Haus 24.

Dort bleibt sie dann.

In Haus 25 ist jetzt ein extra Krankenhaus

für Soldaten.

Das nennt man: Lazarett.

Haus 25, 24 und Haus 23, nach 1950.

ArEGL 109.

Auszug aus der Mitschrift der Vernehmung der Pflegekraft Marie-Luise Heusmann vom 3.11.1947, S. 6.

NLA Hannover Nds. 721 Lüneburg Acc. 8/98 Nr. 3.

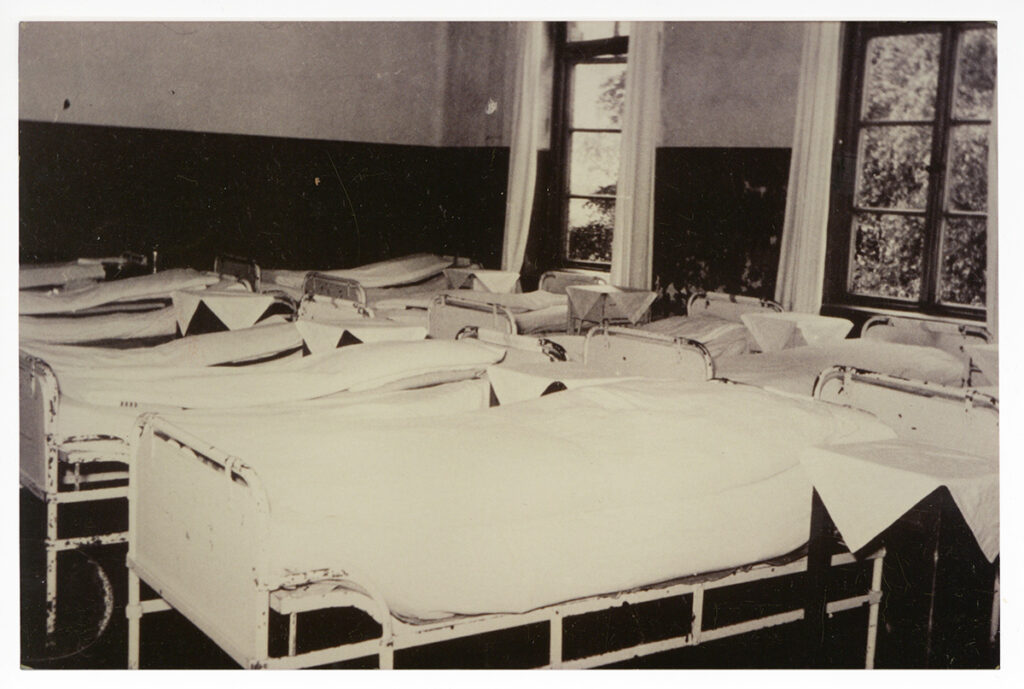

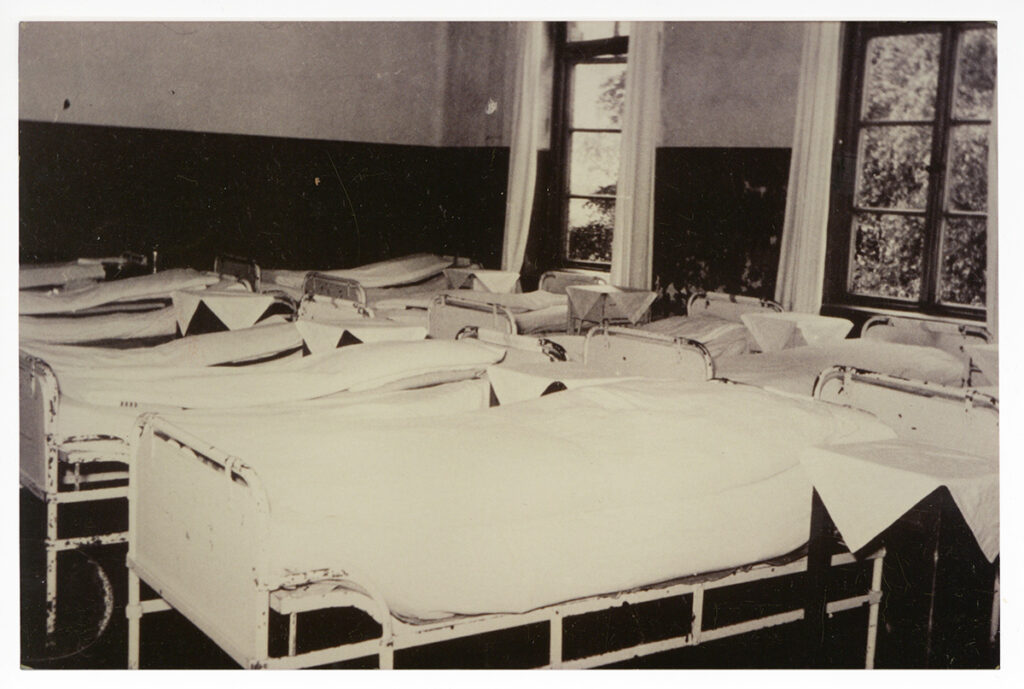

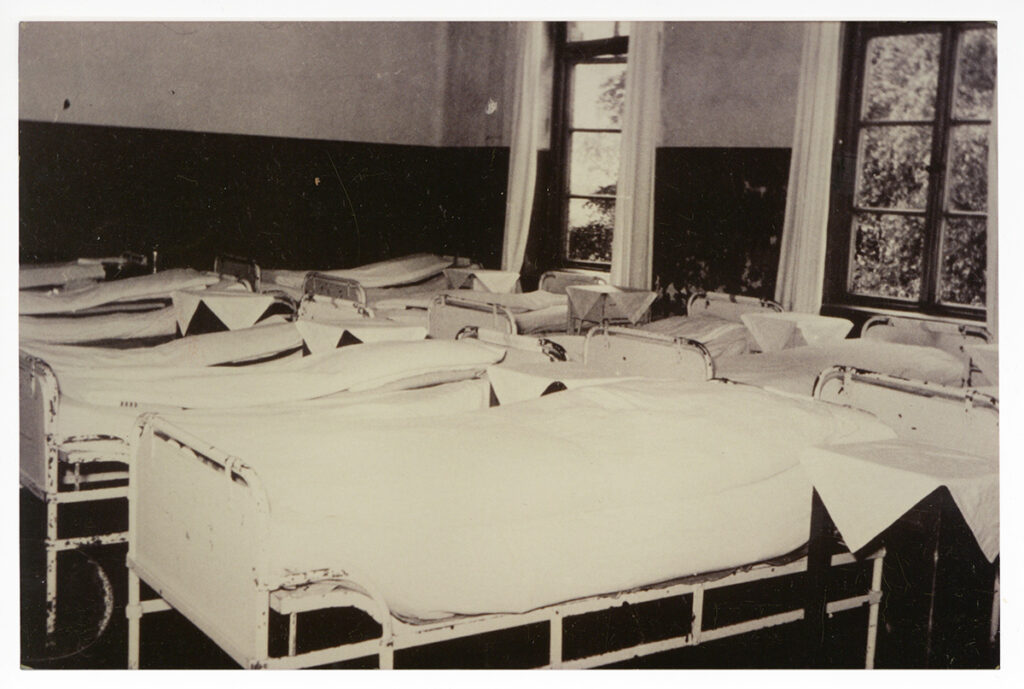

Aufnahme aus einem Schlafsaal der Heil- und Pflegeanstalt Lüneburg, nach 1945. Die Ausstattung war einfach. Es gab nur das Nötigste.

ArEGL 122.

Es gab große Schlafräume mit zu wenigen Betten. Kinder mussten sich Betten teilen oder lagen auf Matratzen auf dem Boden. Es gab zu wenig Wäsche und Pflegemittel. Die Kinder, die nicht auf Toilette gehen konnten, wurden nicht ausreichend gewaschen. Sie erhielten oft keine saubere Kleidung. Betten wurden selten frisch bezogen, die Kinder lagen in ihrer Notdurft. Durch fehlende Sauberkeit und unzureichende Nahrung breiteten sich Haut- und Darmerkrankungen aus.

Marie-Luise Heusmann ist Pflegerin

in der Kinder-Fachabteilung in Lüneburg.

Sie erzählt:

Die Kinder schlafen in einem Schlaf-Raum.

Es gibt zu wenig Betten.

Einige Kinder müssen sich ein Bett teilen.

Einige Kinder schlafen auf Matratzen

auf dem Boden.

Es gibt zu wenig Pflegemittel.

Zum Beispiel: Seife und Tücher.

Nicht alle Kinder können zur Toilette gehen.

Sie werden nicht genug gewaschen.

Sie sind oft schmutzig und

bekommen keine saubere Kleidung.

Auch die Betten sind oft dreckig.

Es gibt zu wenig Sauberkeit.

Es gibt zu wenig Essen.

Darum gibt es viele Krankheiten.

Zum Beispiel: Haut-Krankheiten oder

Darm-Krankheiten.

Das ist ein Foto von einem Schlaf-Raum

in der Kinder-Fachabteilung.

Es gibt nur wenig Möbel.

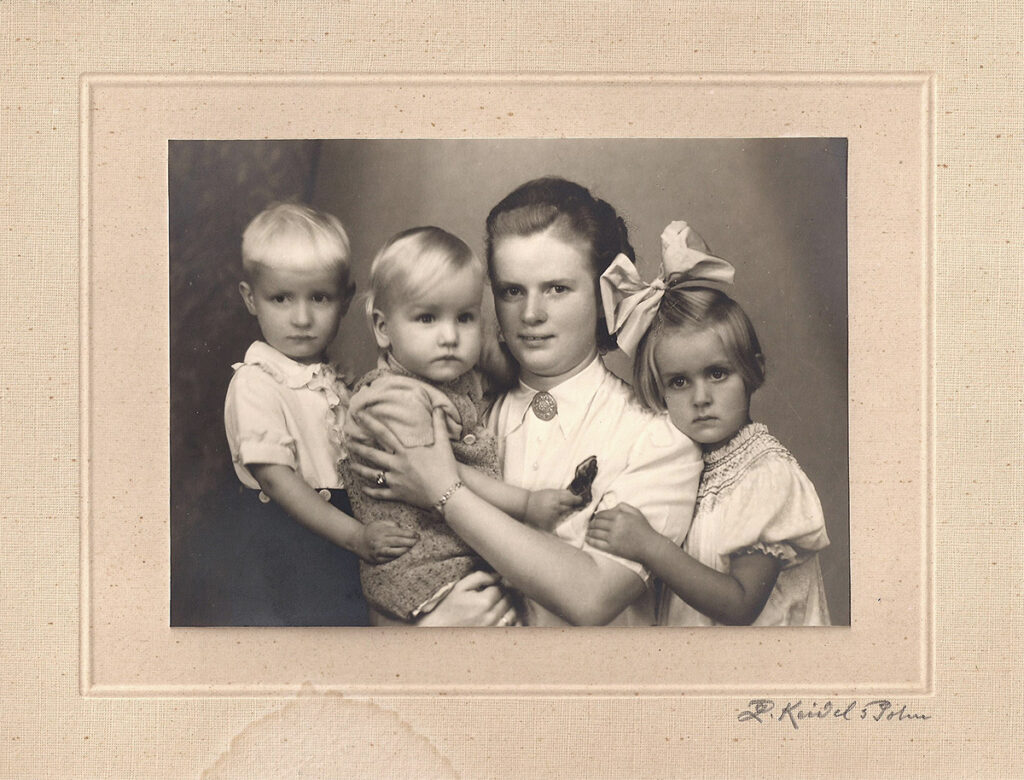

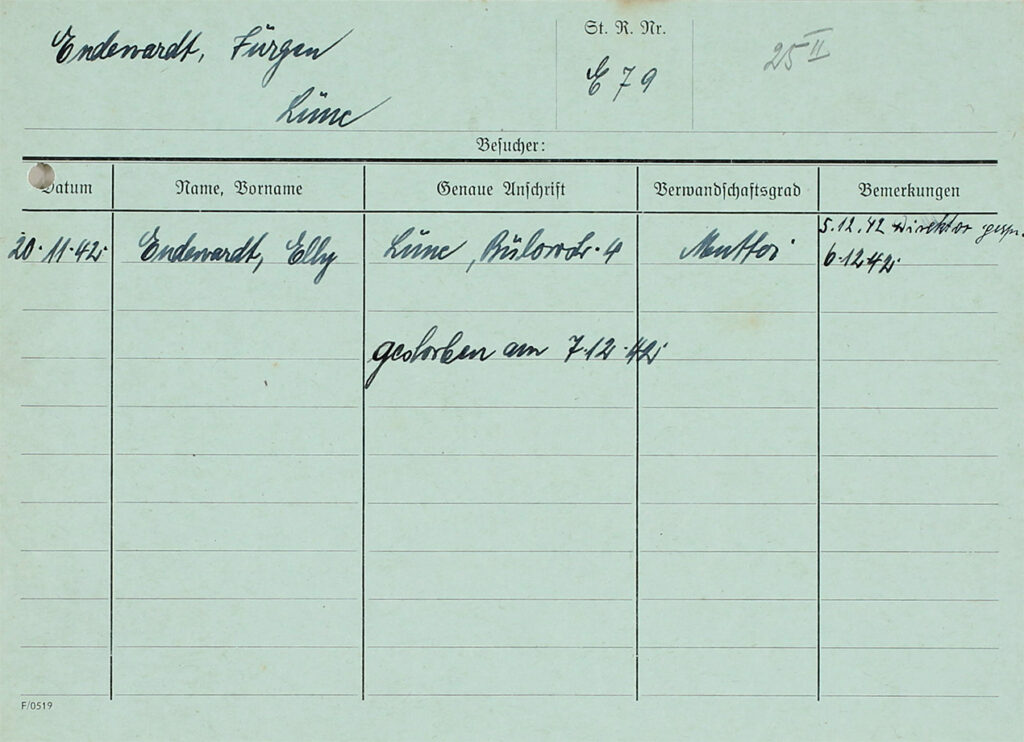

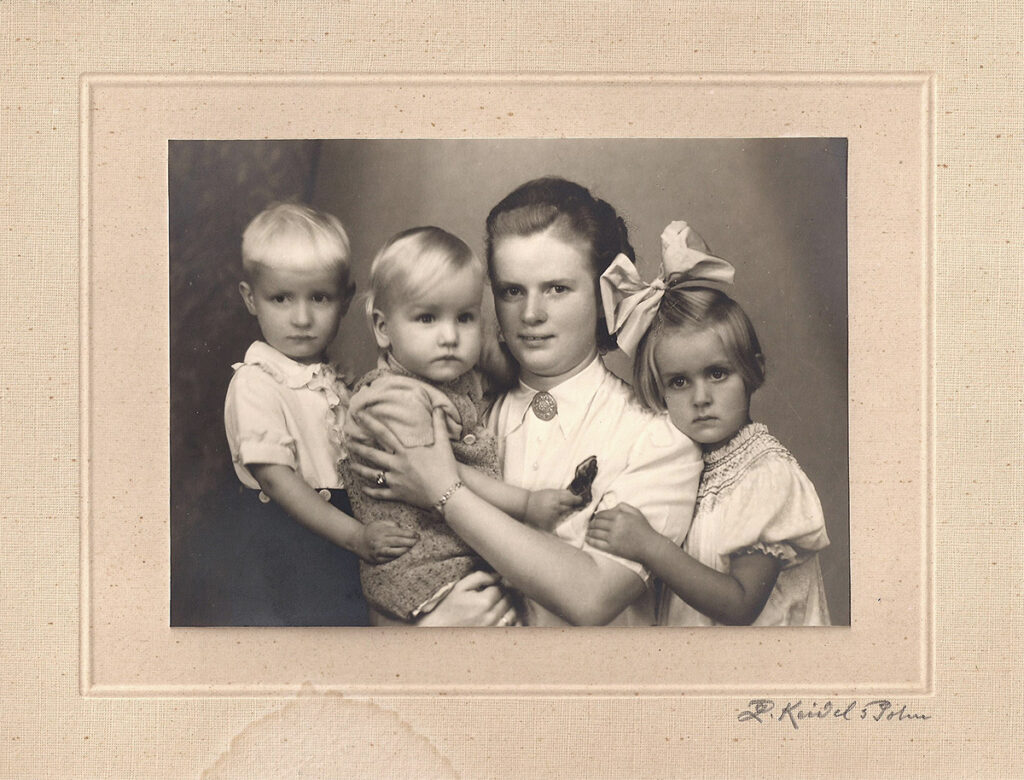

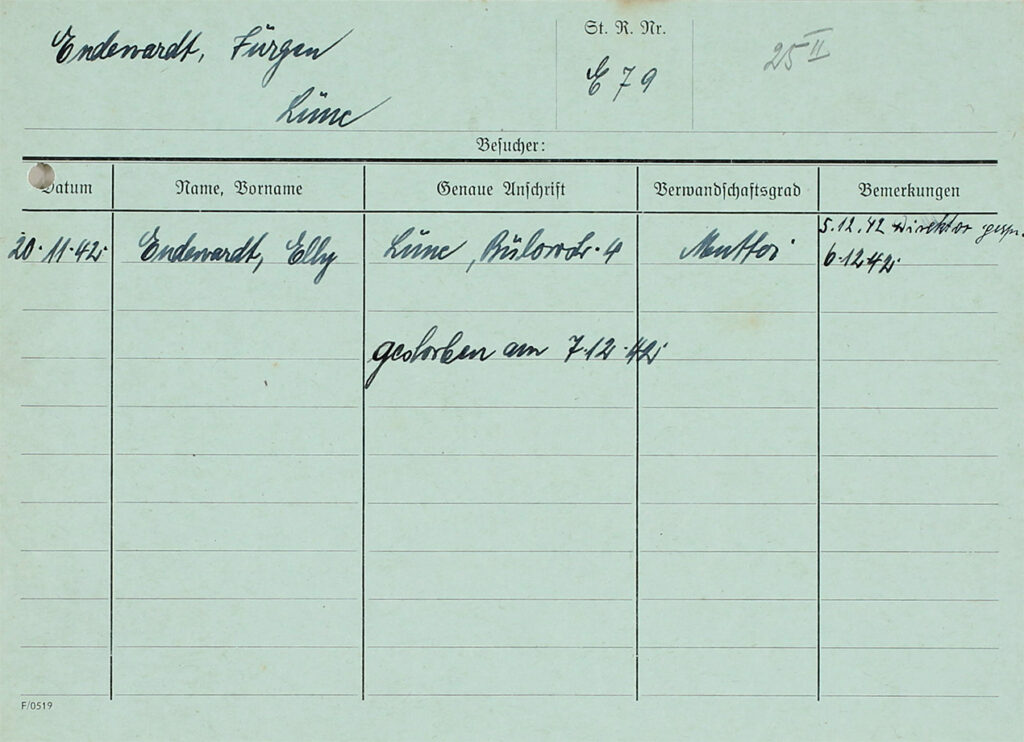

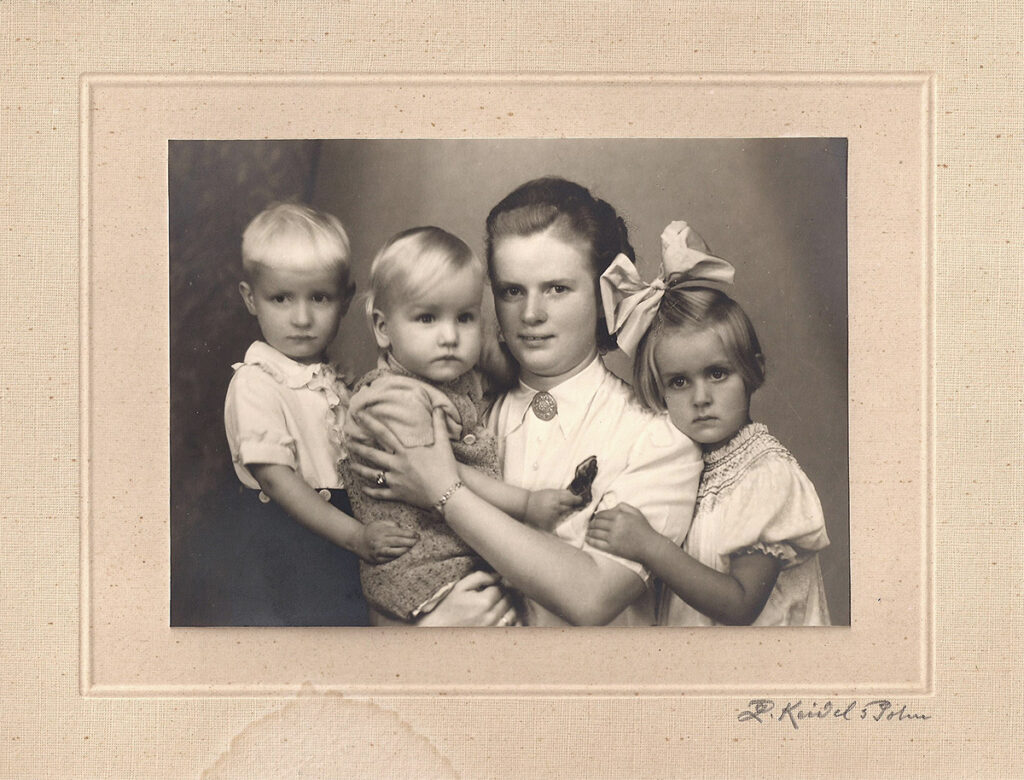

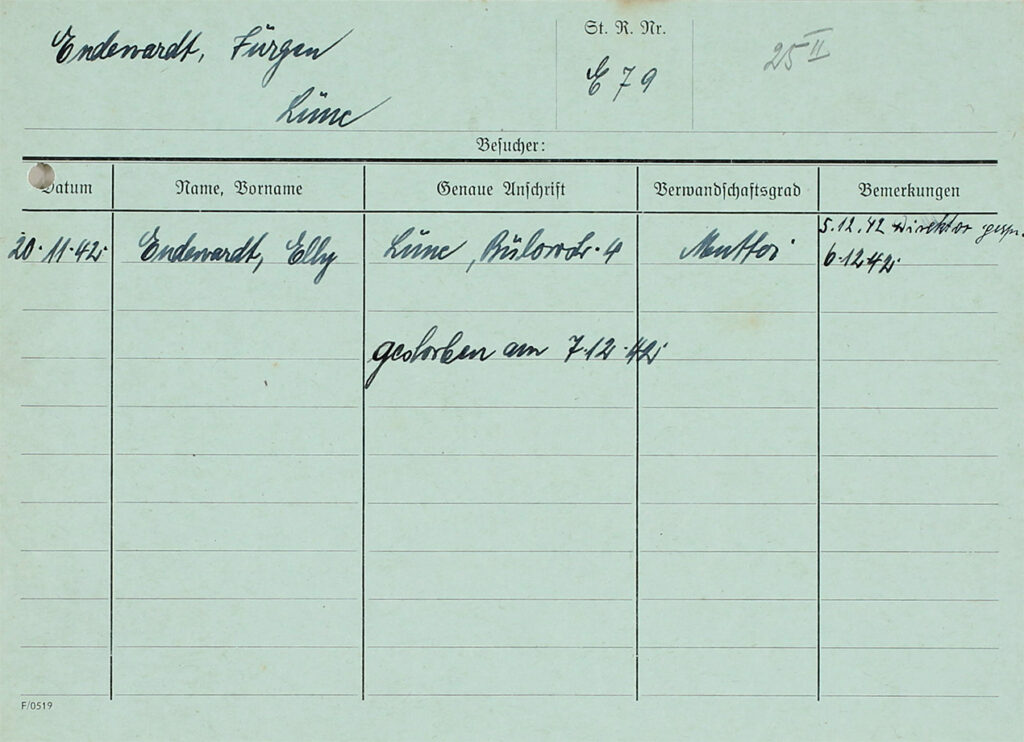

Als Elly Endewardt ihren Sohn Jürgen drei Tage nach seiner Einweisung besuchen wollte, durfte sie nicht zu ihm. Die Mutter betrat trotzdem das Zimmer und sah noch, wie eine Pflegerin schmutzige Bettwäsche unter dem Bett versteckte. Außer einer viel zu dünnen Bettdecke sah sie, dass Jürgen trotz winterlicher Temperaturen splitternackt war. Zwei Wochen später kam sie zwei weitere Male zu Besuch, um mit dem Ärztlichen Direktor zu sprechen. Am nächsten Tag war Jürgen tot.

Jürgen Endewardt ist

in der Kinder-Fachabteilung in Lüneburg.

Seine Mutter ist Elly Endewardt.

Sie besucht Jürgen.

Erst darf sie nicht zu ihm ins Zimmer.

Aber sie geht trotzdem ins Zimmer.

Elly sieht:

Die Pflegerin versteckt dreckige Wäsche.

Jürgen liegt nackt im Bett.

Es ist kalt im Zimmer.

Elly Endewardt kommt noch 2-mal zu Besuch.

Sie spricht mit dem Arzt.

Am nächsten Tag stirbt Jürgen.

Das ist ein Foto von

Elly Endewardt und ihren Kindern:

• Links auf dem Foto ist Dieter.

• In der Mitte vom Foto ist Jürgen.

• Rechts auf dem Foto ist Ute.

Das Foto ist aus dem Jahr 1942.

Elly Endewardt mit ihren drei Kindern Dieter, Jürgen und Ute (von links nach rechts), Sommer 1942.

Privatbesitz Barbara Burmester | Helga Endewardt.

Besucherkarteikarte von Jürgen Endewardt.

NLA Hannover Hann. 155 Lüneburg Acc. 56/83 Nr. 234.

Viele Eltern beklagten, dass mitgegebene Spielsachen verschwanden. Es gab keine Schule und keine Therapien. Es wurde nichts für die Kinder und Jugendlichen getan. Die »arbeitsfähigen« Jugendlichen mussten bei der Garten- oder Feldarbeit helfen. Um die Beschäftigung jüngerer Kinder kümmerte sich niemand bis zu ihrer Ermordung.

Viele Eltern sind nicht zufrieden

mit der Kinder-Fachabteilung.

Sie beschweren sich.

Sie sagen:

Spielzeug verschwindet.

Es gibt keine Schule.

Es gibt keine Behandlung.

Einige Jugendliche müssen arbeiten.

Die jüngeren Kinder arbeiten nicht.

Es gibt keine Beschäftigung für sie.

Zum Beispiel: Spiele.

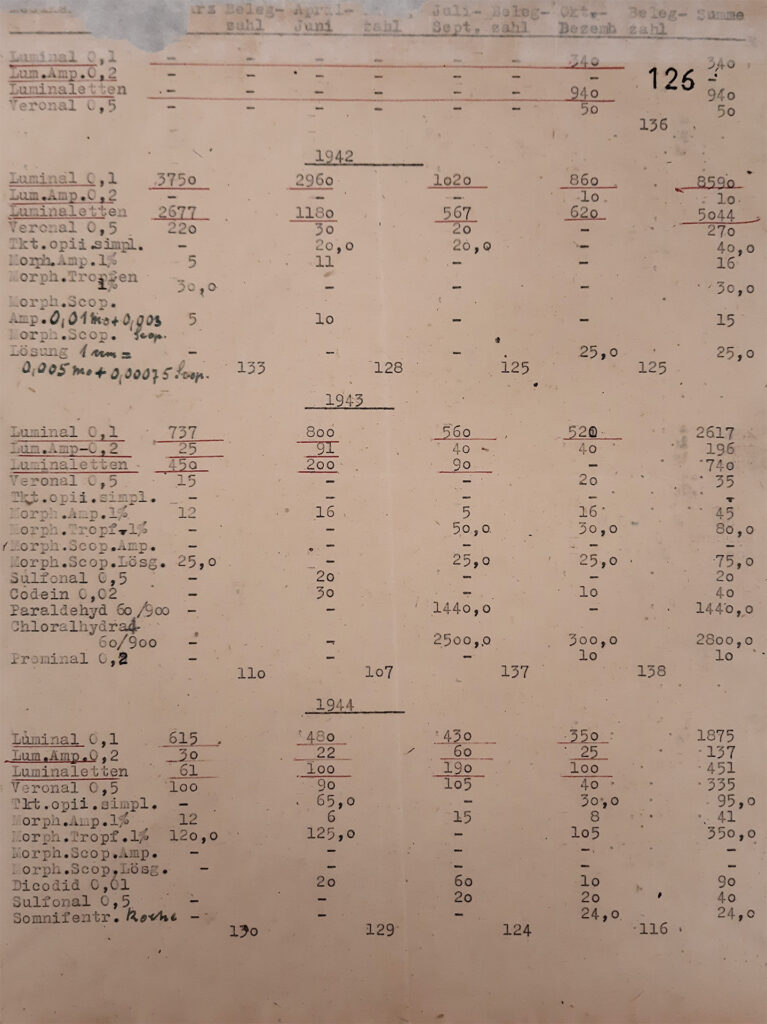

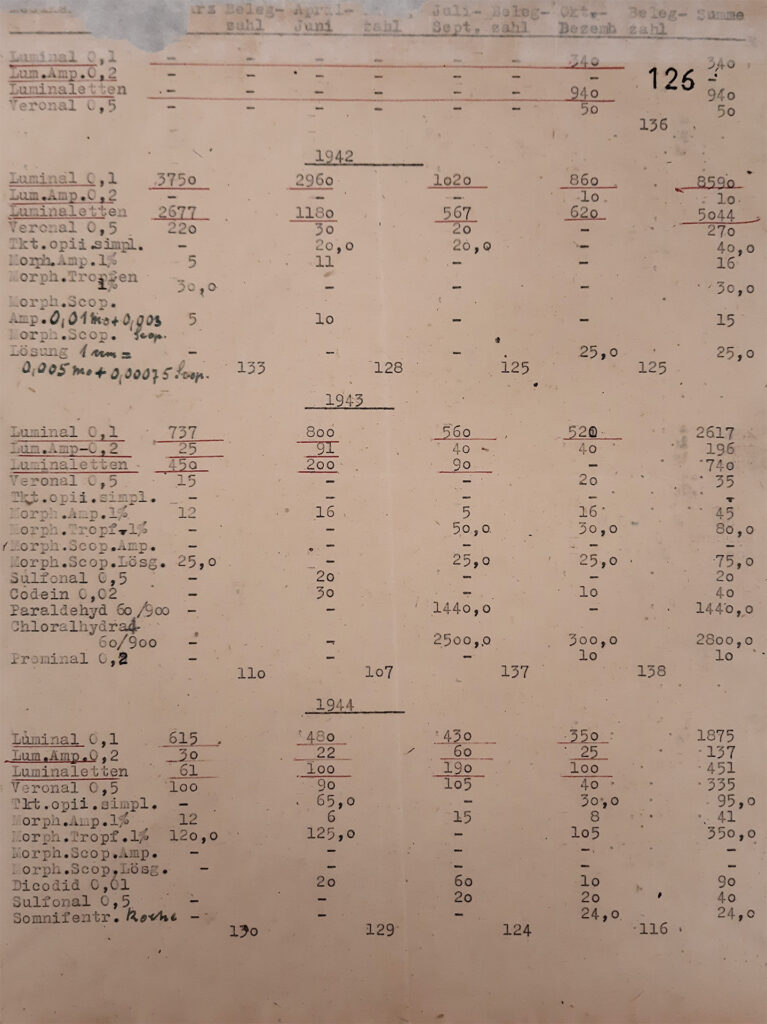

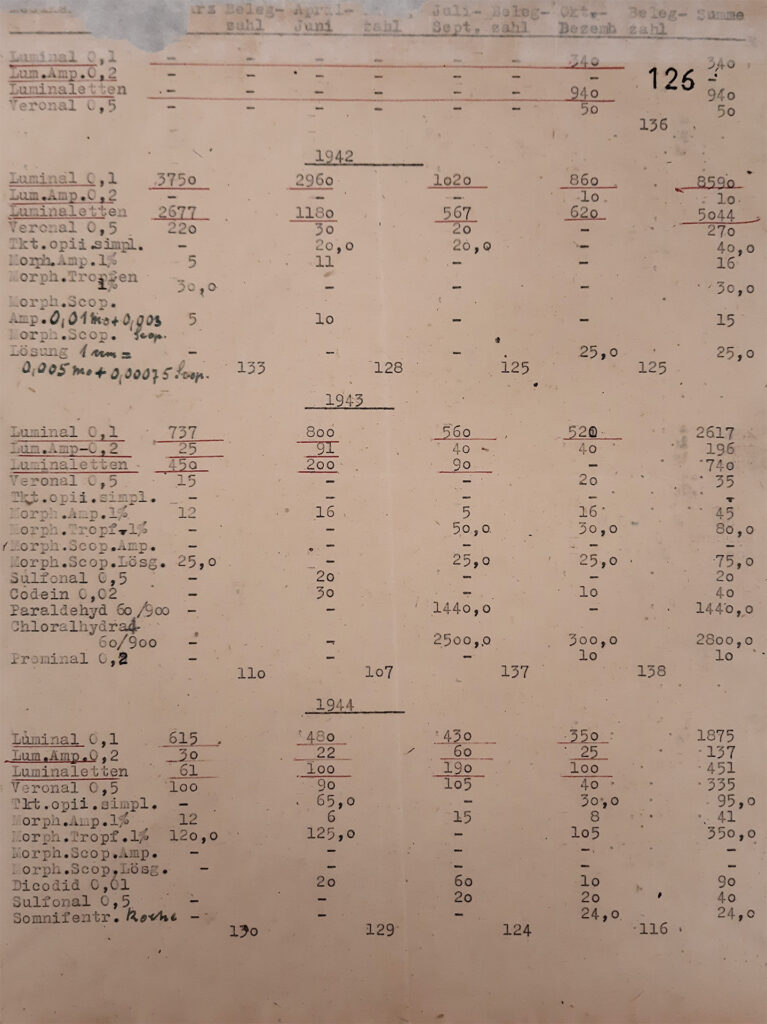

Liste über den Medikamentenverbrauch 1941 – 1948.

NLA Hannover Nds. 721 Lüneburg Acc. 8/98 Nr. 3.

Für den Mord an Kinder und Jugendlichen erfand Paul Nitsche das »Luminal-Schema«. Es wurde zu viel des Anti-Epileptikums Luminal gegeben, das oft als Beruhigungsmittel verordnet wurde. Wenn es über einen längeren Zeitraum gegeben wurde, führte dies zu Flachatmung und erzeugte Atemwegserkrankungen, Kreislauf- und Nierenversagen. So konnte die Ermordung »lebensunwerten Lebens« auf scheinbar natürliche und unauffällige Weise realisiert werden. In Lüneburg kamen neben Luminal auch Veronal und Morphin zum Einsatz.

Der Verbrauch der für die Ermordung eingesetzten Medikamente stieg hundertfach an. Noch bis 1947 blieb die verbrauchte Menge hoch. Dies lässt Rückschlüsse zu.

Viele Kinder werden

in der Kinder-Fachabteilung ermordet.

Der Arzt Paul Nitsche hat dafür

einen Plan gemacht:

Die Ärzte geben den Kinder

zu viel von einem Medikament.

Daran sterben die Kinder.

Ein Medikament heißt: Luminal.

Darum nennt man den Plan: Luminal-Schema.

Die Ärzte benutzen für den Mord

diese Medikamente:

• Luminal.

• Veronal.

• Morphin.

Die Kinder bekommen von den Medikamenten Atemwegs-Erkrankungen.

Zum Beispiel: Lungen-Entzündung

Einige Kinder bekommen auch

Kreislauf-Versagen oder Nieren-Versagen.

Daran sterben die Kinder.

Sie werden ermordet.

Aber der Mord fällt nicht auf.

Denn die Kinder sterben an einer Krankheit.

Es sieht so aus,

als ob es ein natürlicher Tod ist.

Aber das ist eine Lüge.

Die Kinder sterben,

weil die Ärzte ihnen zu viele Medikamente geben.

Auf dieser Liste stehen die Medikamente,

mit denen Kinder ermordet wurden.

Die Liste zeigt:

Wie viele Medikamente haben

die Ärzte verbraucht.

In der Nazi-Zeit verbrauchen die Ärzte

sehr viele Medikamente.

Die Liste zeigt aber auch:

Die Ärzte verbrauchen im Jahr 1947

immer noch viele Medikamente.

Da ist die Nazi-Zeit schon vorbei.

Vielleicht haben die Ärzte nach der Nazi-Zeit immer noch Kinder ermordet.

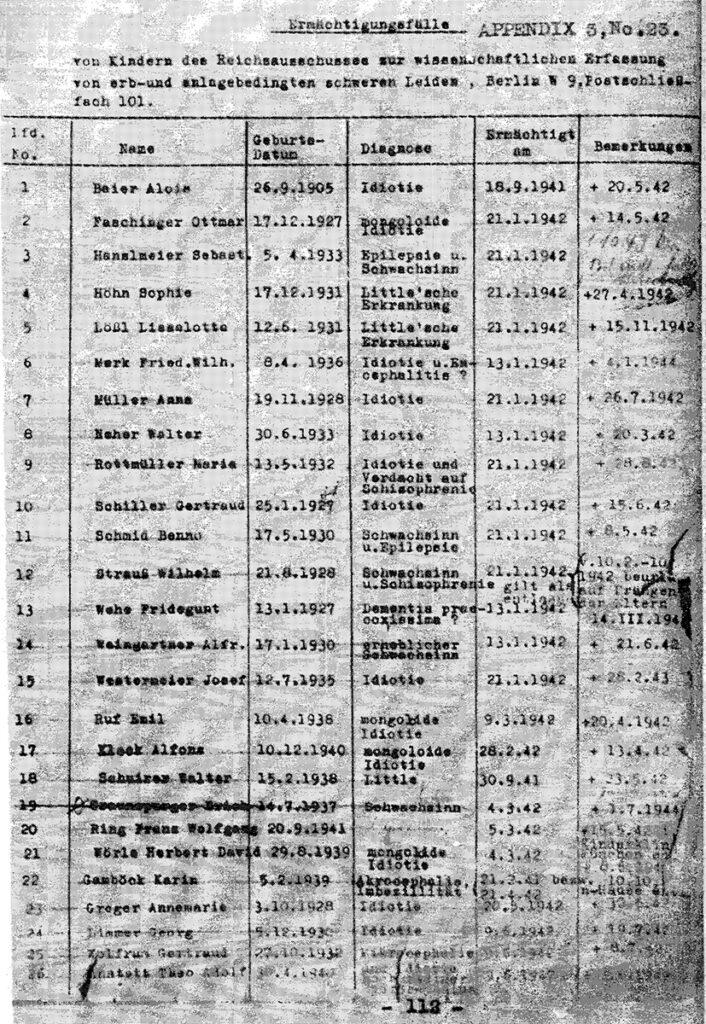

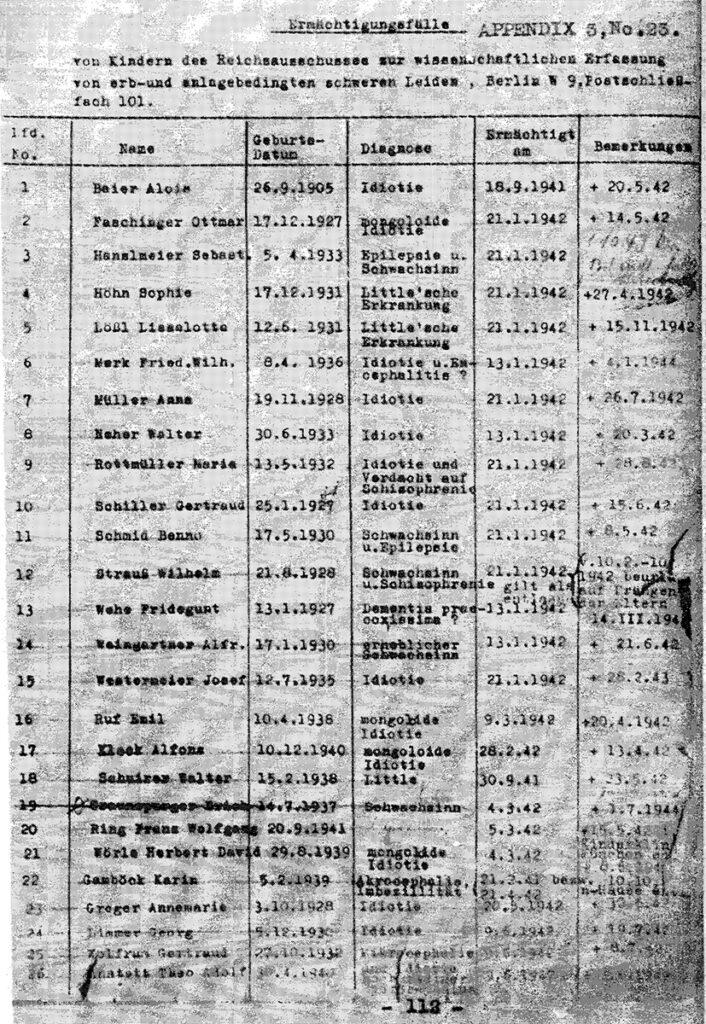

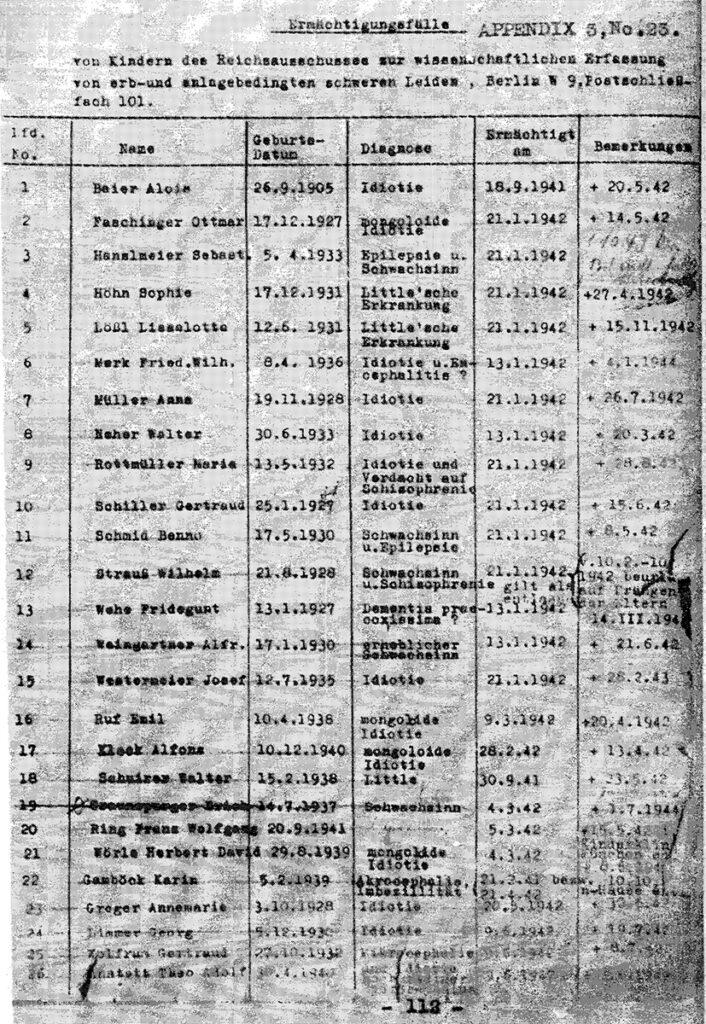

Das Leben der Kinder und Jugendlichen hing davon ab, ob die Ärzte sie als »entwicklungs-« und »bildungsfähig« bewerteten. Ein schlechter Entwicklungsstand oder geringe Fähigkeiten wurden als »lebensunwert« beurteilt. Auch wenn aufwendige Pflege benötigt wurde, kam eine »Behandlung«, also der Krankenmord infrage. Die Ärzte erhielten vom »Reichsausschuss« sogenannte »Ermächtigungen«. Davon wurden oft mehrere an einem Tag ausgestellt, wie diese Liste aus Eglfing-Haar belegt.

Willi Baumert und Max Bräuner sind Ärzte.

Sie entscheiden in der Nazi-Zeit,

welches Kind leben darf.

Und sie entscheiden,

welches Kind sterben muss.

Die Ärzte beurteilen:

• kann ein Kind sprechen.

• kann ein Kind lesen.

• kann sich ein Kind entwickeln.

• braucht ein Kind viel Hilfe.

• braucht ein Kind Pflege.

Danach entscheiden die Ärzte :

Darf ein Kind leben.

Oder soll ein Kinder getötet werden.

Der Reichsausschuss von den Nazis erlaubt den Ärzten, Kinder zu töten.

Die Nazis nennen das: Ermächtigung.

Oft gab es mehrere Ermächtigungen

an einem Tag.

Das zeigt diese Liste.

Auszug aus einer Liste von Ermächtigungsfällen aus dem Bericht von Major Leo Alexander für den Nürnberger Ärzteprozess, in: Lutz Kälber: Kindermord in Nazi-Deutschland, in Gesellschaften 2, 2012.

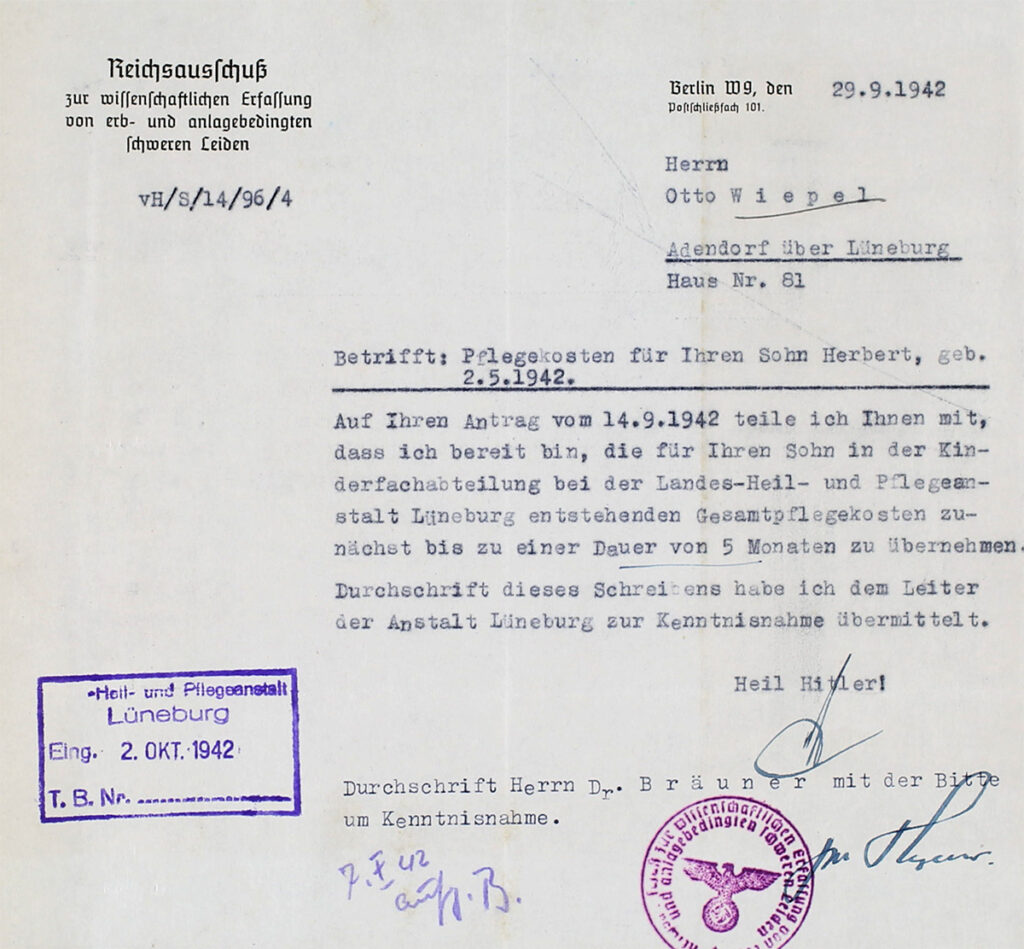

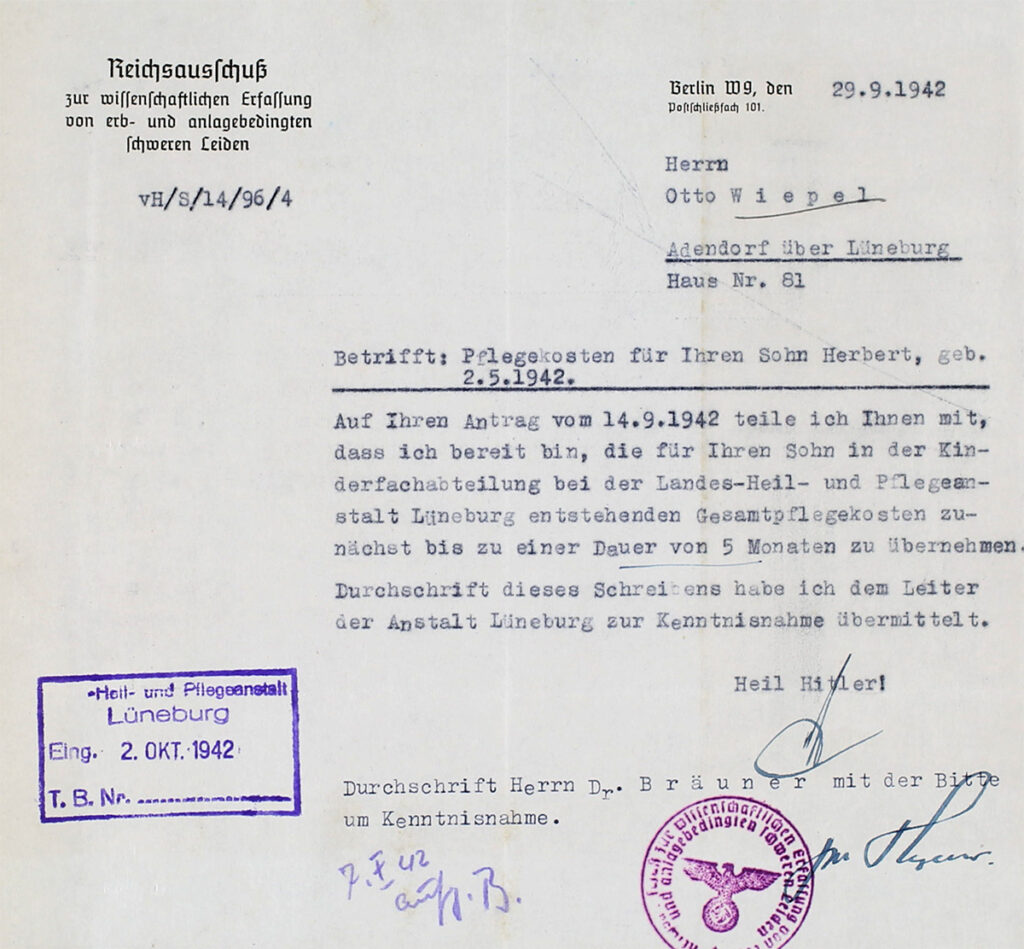

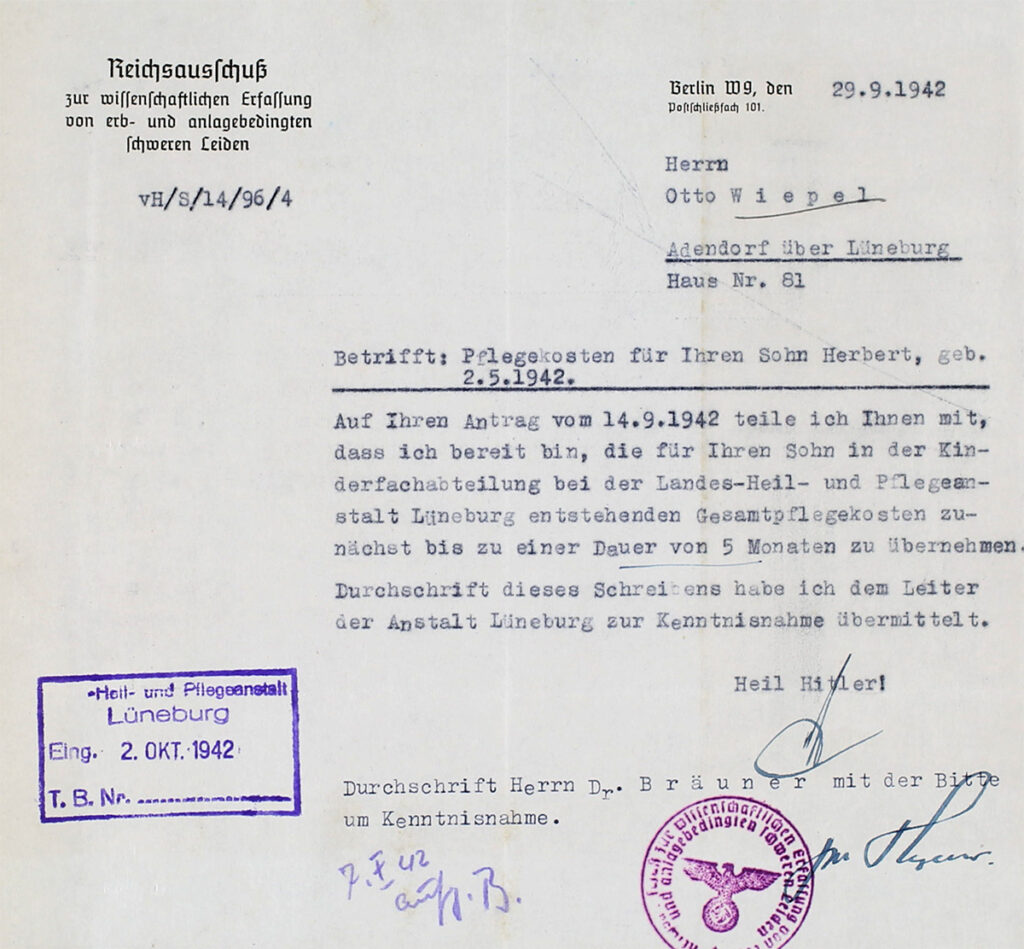

Brief des Reichsausschusses an Otto Wiepel vom 29.9.1942.

NLA Hannover Hann. 155 Lüneburg Acc. 56/83 Nr. 428

Otto Wiepel wurde vom »Reichsausschuss« zugesichert, dass dieser die Kosten für Herberts Pflege für fünf Monate übernehmen würde. Das war die kalkulierte Lebenserwartung, denn nur so viel Zeit blieb den Ärzten und Behörden für die Durchführung und Verwaltung von Herberts Ermordung.

Otto Wiepel hat einen Sohn

in der Kinder-Fachabteilung in Lüneburg.

Der Reichsausschuss schickt seinen Sohn

in die Kinder-Fachabteilung.

Der Reichsausschuss sagt:

Wir bezahlen die Pflege für den Sohn

für 5 Monate.

Der Sohn lebt nur 5 Monate

in der Kinder-Fachabteilung.

Dann wird der Sohn ermordet.

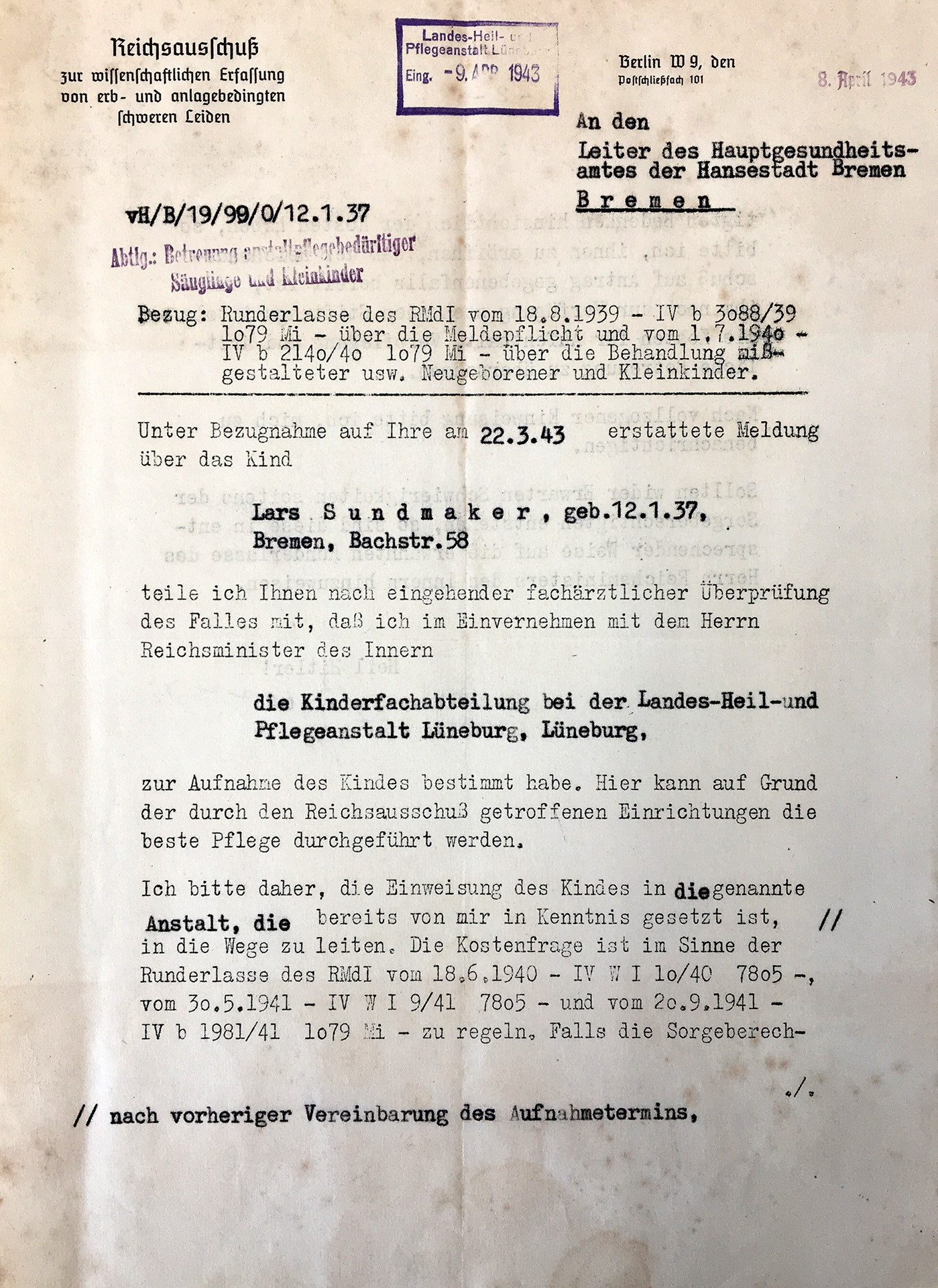

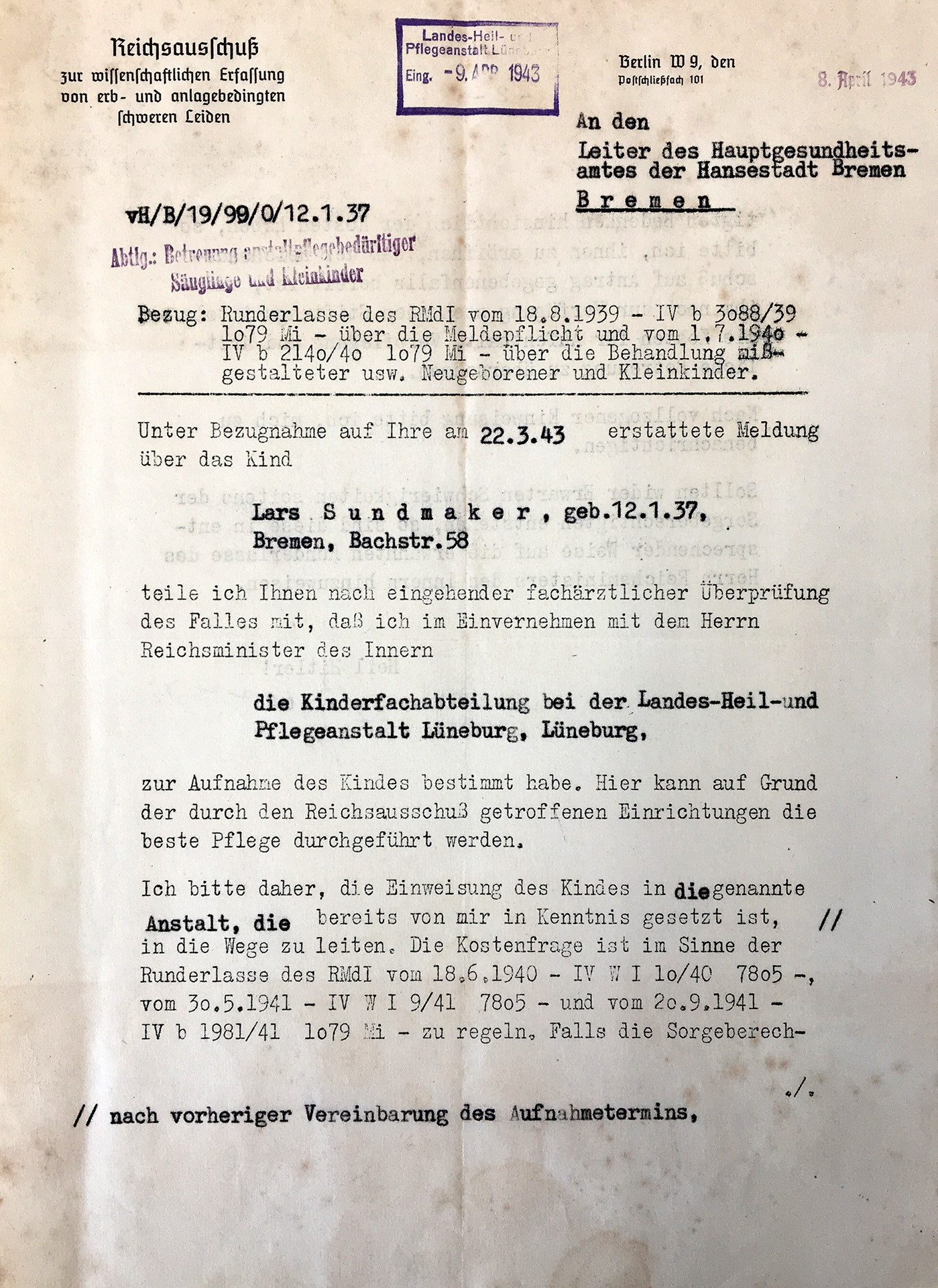

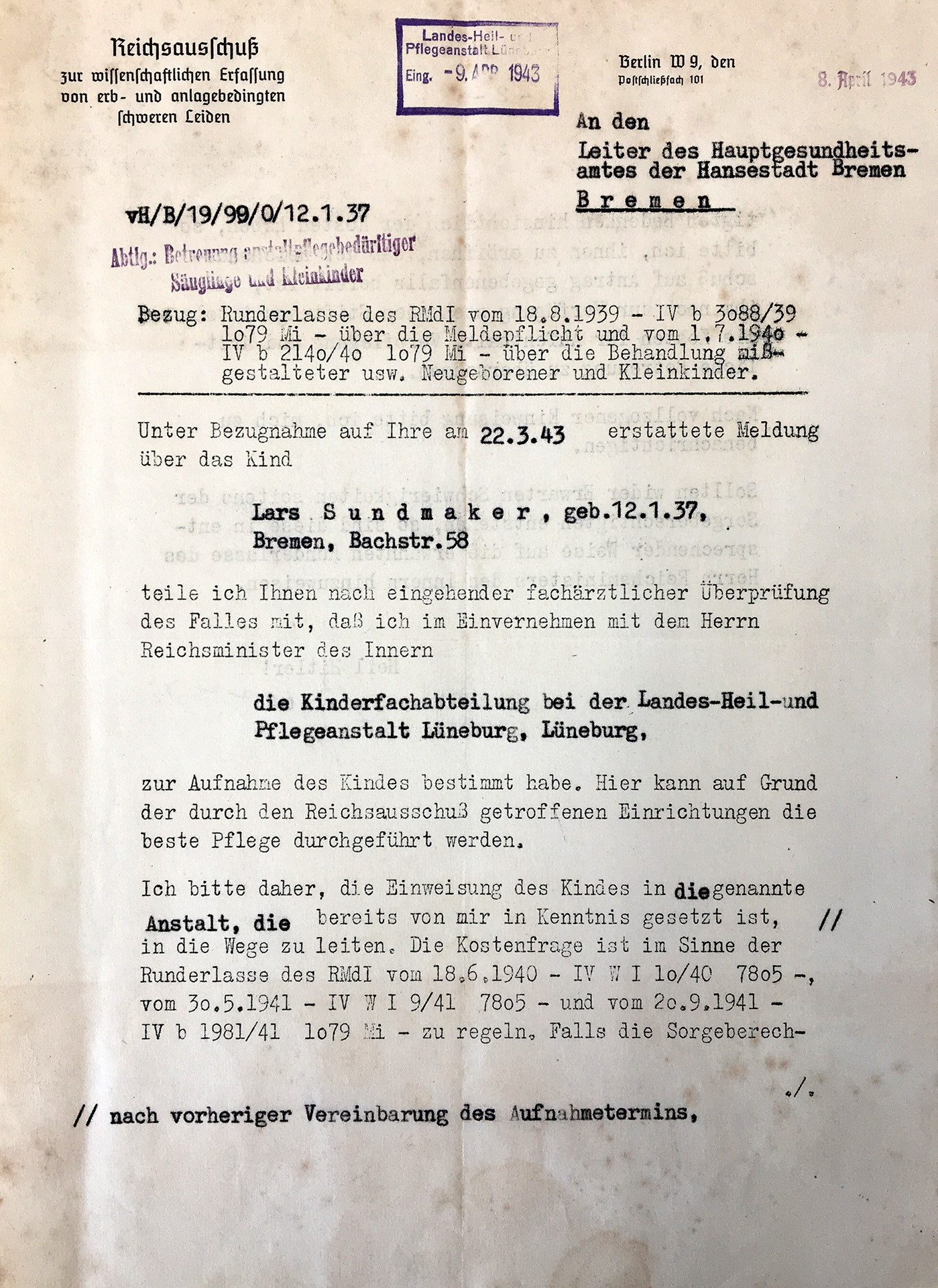

Einweisungsverfügung vom »Reichsausschuss« zur Aufnahme von Lars Sundmäker in die »Kinderfachabteilung« Lüneburg, 8.4.1943.

NLA Hannover Hann. 155 Lüneburg Acc. 56/83 Nr. 405.

Der »Reichsausschuss« bestimmte die Aufnahme in eine »Kinderfachabteilung«. Auch gab er eine »Behandlungsempfehlung« ab. Ohne die Kinder und Jugendlichen gesehen oder kennengelernt zu haben, vermerkten die Gutachter Catel, Wentzler und Heinze auf dem Bogen ein rotes Kreuz, ein blaues Minus oder ein »B«. Die Lüneburger »Kinderfachabteilung« erhielt eine entsprechende »Behandlungsempfehlung« zurück. Das Kreuz bedeutete Ermordung, das »B« stand für »Beobachtung« und bedeutete Rückstellung, das blaue Minus bedeutete keine Ermordung.

Die Ärzte in der Kinder-Fachabteilung beobachten die Kinder.

Sie schreiben alles über die Kinder

auf einen Untersuchungs-Bogen.

Dann schicken sie den Untersuchungs-Bogen

an den Reichsausschuss.

3 Ärzte sind im Reichsausschuss:

Werner Catel, Ernst Wentzler und Hans Heinze.

Die 3 Ärzte vom Reichsausschuss kennen

die Kinder nicht.

Sie wissen nur das,

was auf den Untersuchungs-Bögen steht.

Aber sie entscheiden,

was mit den Kindern passiert.

Sie schreiben auf den Untersuchungs-Bogen:

• ein rotes Kreuz

Das heißt:

Das Kind soll ermordet werden.

• ein blaues Minus

Das heißt:

Das Kind darf zu Hause weiterleben.

• ein B

Das heißt:

Die Ärzte sollen das Kind weiter beobachten.

Der Reichsausschuss schickt die Untersuchungs-Bögen dann zurück an die Kinder-Fachabteilung.

Die Kinder-Fachabteilung muss tun,

was auf den Untersuchungs-Bögen steht.

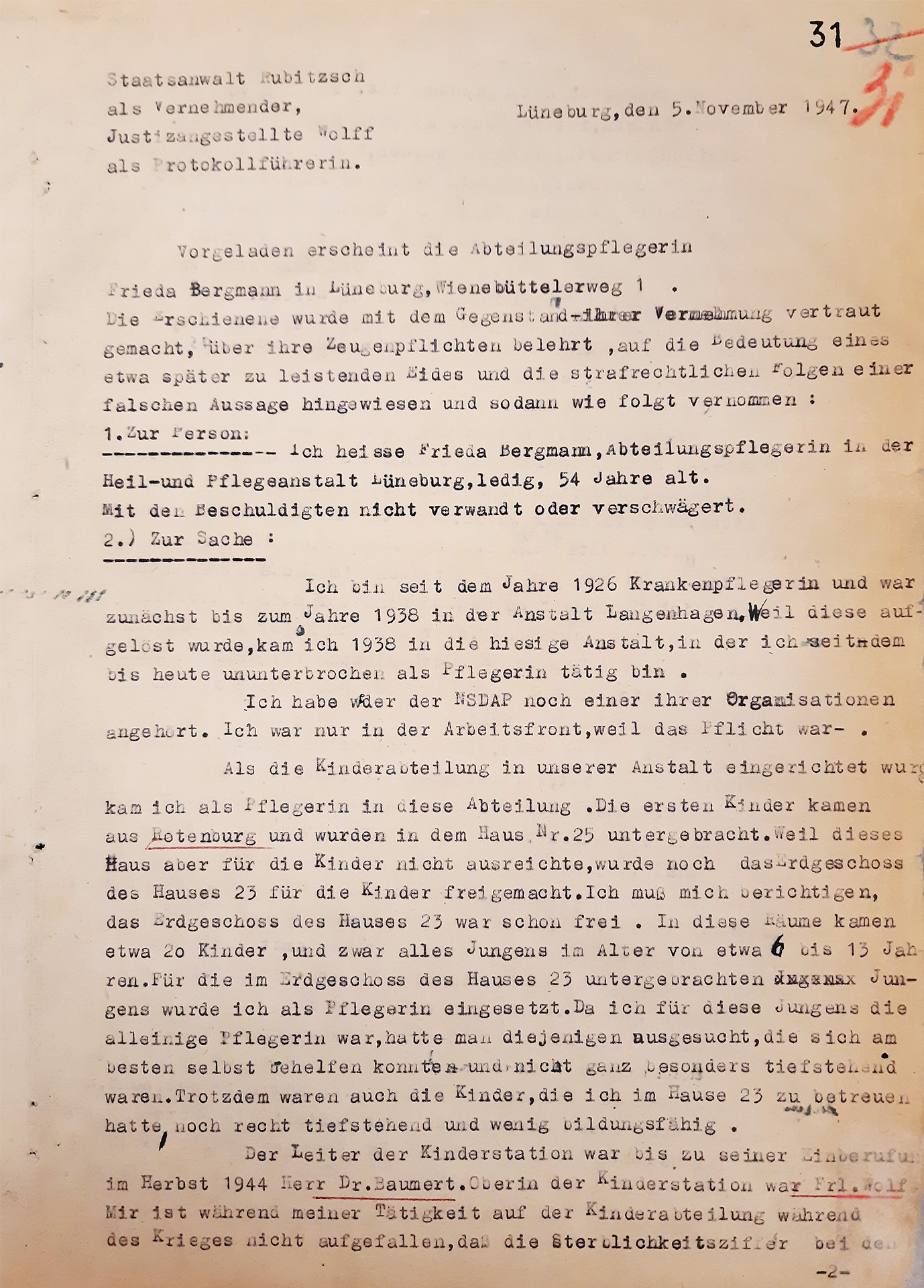

Es gibt keine klare Trennung zwischen den Verbrechen, die man erwachsenen Erkrankten angetan hat, und Jugendlichen bzw. nicht Volljährigen. In der »Kinderfachabteilung« untergebrachte Jugendliche wurden ab einem Alter von 14 Jahren für eine Unfruchtbarmachung angezeigt und zwangssterilisiert. Es kam auch zu Verlegungen in Tötungsanstalten und Jugendkonzentrationslager, in denen sie körperlicher Gewalt bis hin zur Tötung ausgesetzt waren. Die in Lüneburg untergebrachten Kinder und Jugendlichen blieben nur von Verlegungen in Jugendkonzentrationslager verschont.

In der Nazi-Zeit sind auch Jugendliche

in der Kinder-Fachabteilung.

Sie werden unfruchtbar gemacht,

wenn sie über 14 Jahre alt sind.

Man nennt das: Sterilisation.

Einige Jugendliche kommen

in eine Tötungs-Anstalt.

Einige Jugendliche kommen

in ein KZ für Jugendliche.

Das ist kurz für: Konzentrations-Lager.

Sie erleben körperliche Gewalt.

Einige werden ermordet.

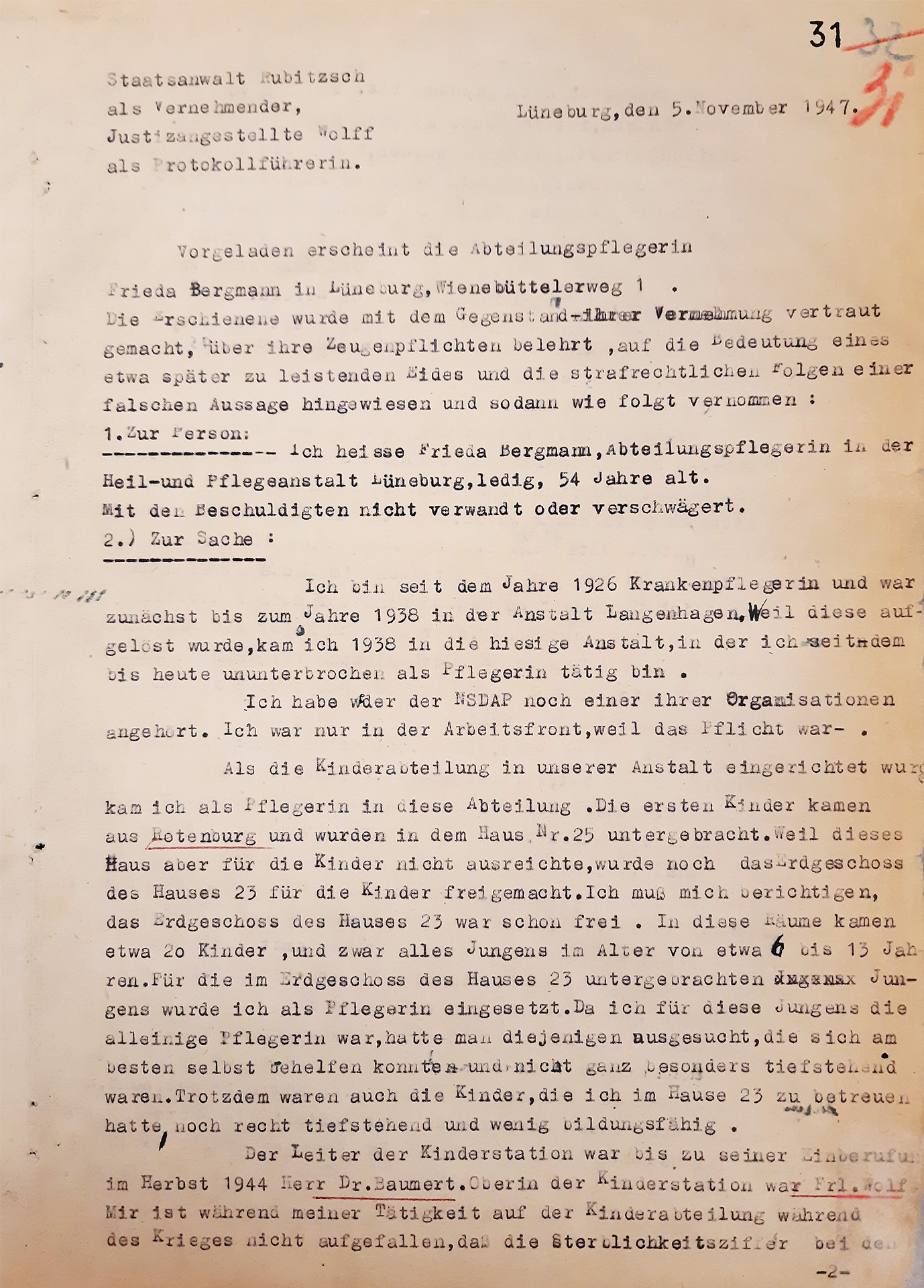

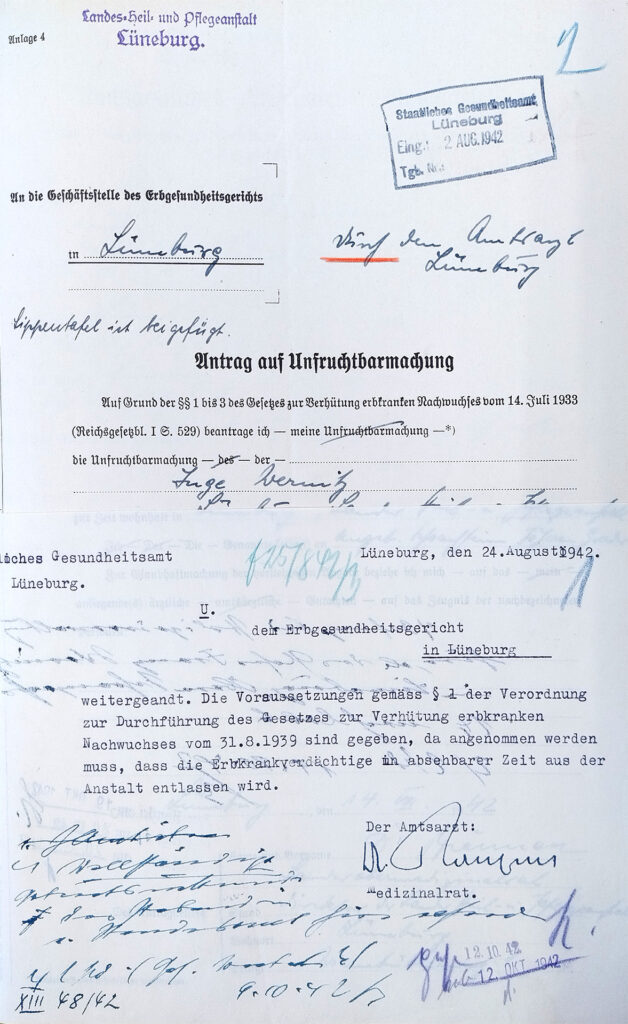

Anträge auf Unfruchtbarmachung von Max Bräuner und Hans Rohlfing vom August 1942.

NLA Hannover Hann. 138 Lüneburg Acc. 103/88 Nr. 609.

Die Unfruchtbarmachung war für Ingeborg Wernitz die zwingende Voraussetzung, um aus der »Kinderfachabteilung« entlassen werden zu können. Vier Monate vor ihrem 14. Geburtstag wurde der Antrag gestellt. Sie wurde am 21. Januar 1943 zwangssterilisiert und erst danach entlassen.

Ingeborg Wernitz ist Jugendliche.

Sie ist in der Kinder-Fachabteilung in Lüneburg.

Sie bekommt eine Zwangs-Sterilisation

als sie 14 Jahre alt ist.

Danach darf sie nach Hause.

Das ist im Jahr 1943.

Aus der Lüneburger Heil- und Pflegeanstalt wurden mindestens elf Jugendliche unter 18 Jahren am 8. September 1943 in die Tötungsanstalt Pfafferode verlegt. Acht von ihnen wurden dort ermordet, nur ein einziger wurde vor Kriegsende entlassen. Eine Jugendliche überlebte zwar, wurde jedoch 1947 zurück nach Lüneburg überstellt.

11 Jugendliche aus der Kinder-Fachabteilung

in Lüneburg kommen nach Pfafferode.

Pfafferode ist eine Tötungs-Anstalt.

8 von den Jugendlichen werden dort ermordet.

Die in Pfafferode ermordeten Jugendlichen sind:

Ilse Allrütz (1928 – 1944)

Richard Bergmann (1926 – 1943)

Rolf Erbguth (1928 – 1943)

Harald Frandsen (1926 – 1944)

Kurt Nolte (1925 – 1944)

Gerda Plenge (1927 – 1945)

Otto Schulz (1927 – 1944)

Ekatharina Taranowa (1926 – 1944)

Sie heißen:

• Ilse Allrütz (1928 – 1944)

• Richard Bergmann (1926 – 1943)

• Rolf Erbguth (1928 – 1943)

• Harald Frandsen (1926 – 1944)

• Kurt Nolte (1925 – 1944)

• Gerda Plenge (1927 – 1945)

• Otto Schulz (1927 – 1944)

• Ekatharina Taranowa (1926 – 1944)

Nur ein Jugendlicher wird

aus der Tötungs-Anstalt Pfafferode entlassen.

»CHILDren’s EUTHANASIA«

From 1940 onwards, the first »children’s departments« began operating in Görden, Dösen, Marsberg and Vienna (»Spiegelgrund«). As the reporting requirement was hardly ever complied with and affected parents showed little willingness to participate, the Reich Ministry of the Interior issued a decree. Among other things, the age of children subject to reporting was raised to 16. As a result, further »special children’s departments« were set up and the number of child murders increased. The Lüneburg »special children’s department« began operating and developed into one of the main murder sites.

Excerpt from the decree of the Reich Ministry of the Interior dated 20 September 1941.

NLA Hanover Nds. 721 Lüneburg Acc. 8/98 No. 3/9.

The relevant authorities were emphatically instructed to fulfil their reporting obligations. They were to convince parents that the measure was good for the community and for families. Apparently, the results of a survey conducted by Ewald Meltzer in 1920 were not accurate. The study, which was not published until 1925, stated that 78 percent of parents wanted their children with disabilities to be »saved.« But that was not true.

Registered children and adolescents were examined by the »Reich Committee« and local doctors. The assessment of whether a child or adolescent was »capable of development and education« determined whether they lived or died. Those deemed »incapable« were murdered, and their brains were used for medical research.

More than 30 »children’s wards« were set up in homes, hospitals and institutions for the purpose of »children’s euthanasia«. Not all of them existed during the same period. Around 6,800 children and adolescents are known to have died in »children’s wards«, at least 6,500 of whom were murdered.

Even outside the »children’s wards«, »children’s euthanasia« occurred in many places on an unknown scale.

Certificate of death dated 13 September 1941.

Hamburg State Archives 352-8/7 Langenhorn State Hospital No. 86294.

Before the »children’s ward« in Lüneburg was established, at least ten children from the future catchment area were admitted to the two »children’s wards« in Hamburg, Rothenburgsort (1) and Langenhorn (9):

- Hermann Beekhuis (Leer)

- Helmuth Beneke (Bremervörde)

- Gerda Cordes (Uelzen)

- Marianne Harms (Bardowick)

- Hillene Hellmers (Leer)

- Irmgard Jagemann (Bremen)

- Rosemarie Kablitz (Wilstedt)

- Edda Purwin (Lüneburg)

- Günther Schindler (Wilhelmshaven)

- Hans-Ludwig Würflinger (Bremen)

Five returned home between 1942 and 1943, while the others were murdered. The youngest victim was Hermann Beekhuis. He was murdered at the age of three and a half months in the Rothenburgsort Children’s Hospital. The official date of death is falsified.

Excerpt from the interrogation of Frieda Bergmann on 5 November 1947.

NLA Hanover Lower Saxony 721 Lüneburg Acc. 8/98 No. 3.

On 9 and 10 October 1941, 138 children and adolescents were admitted to the »children’s ward« in buildings 25 and 23 of the Lüneburg mental hospital. They came from the Rotenburg institutions of the Inner Mission. Only nine boys and seven girls from this first group survived. Frieda Bergmann, a nurse in the Lüneburg »children’s ward,« was interviewed in Lüneburg shortly after the war.

Aerial view of the Rotenburg institutions of the Inner Mission, postcard, before 1945.

ArEGL 99.

The Rotenburg institutions of the Inner Mission were to be used as an auxiliary hospital for Bremen victims of the air war. To this end, the children’s ward was closed and the children being treated there were divided up. Ninety-nine children were sent to the von Bodelschwingh institutions in Bethel, Bielefeld, and 24 children were sent to the Eben-Ezer Foundation in Lemgo. The children who were unable to attend school were transferred to the »children’s ward« in Lüneburg.

For many children and young people with disabilities from the province of Hanover, the Rotenburg institutions of the Inner Mission were a large home. The photos shown here certainly include children and young people who were later murdered in Lüneburg. In the picture of the boys in front of the Wichernhaus, for example, Eckart Willumeit from Celle can be seen on the left.

Young people with Brother Karl Stallbaum in front of the Wichernhaus of the Rotenburg Works of the Inner Mission, around 1938. Photographer Kurt Stallbaum.

Archive of the Rotenburg Works of the Inner Mission.

Group photo of the children’s transport from Hanover-Langenhagen. On the left is the director from Rotenburg, Pastor Johannes Buhrfeind. Behind him on the right is the ward nurse or »house father« Grützmacher.

Archive of the Rotenburg Works of the Inner Mission.

Among the children who were transferred to Lüneburg were 25 who had been moved from the Hanover-Langenhagen mental hospital to Rotenburg on 18 March 1938 after the children’s clinic in Langenhagen had been closed. In addition to Eckart Willumeit, these included Friedrich Daps, Waldemar Borcholte and Hans-Herbert Niehoff. They must be four of the children in the photo.

Between 1941 and 24 August 1945, a total of at least 762 children and adolescents aged between one day and 16 years were admitted to the »children’s ward« in Lüneburg. Over 440 of them did not survive their stay. It is unclear whether a further 61 children and adolescents survived.

The mortality rate in the »children’s ward« in Lüneburg was over 60 percent. Since not all fates are known, it may be even higher.

Most of the children and adolescents were murdered in 1943 (132) and 1944 (120). Even after the end of the war, the deaths continued. The last admission to the »children’s ward« in Lüneburg took place on 23 August 1945. The patient was one-and-a-half-year-old Heiko Bromm from Hannoversch-Münden. He died two months later.

Whether and how many children and adolescents were referred to a »children’s ward« depended on the actions of parents, midwives, teachers and health authorities. These varied greatly from region to region. There were regions from which no children or only one child was reported and admitted (e.g. Cloppenburg and Vechta). A striking number of children were admitted to the »children’s ward« from Hanover (135), Bremen (39), Celle (33), Lüneburg (33), Bremerhaven (31) and Hildesheim (31).

The children and adolescents in the Lüneburg »children’s ward« came from what are now the federal states of Lower Saxony, Bremen, Hamburg and North Rhine-Westphalia. This map of the catchment area at that time shows the cities and districts from which they were admitted to the Lüneburg »children’s ward« and how many of them there were.

Herta Ley, around spring 1932.

ArEGL.

The Leer health authority had some very dedicated employees. Eight of the 13 children from Leer were murdered. Among them was Herta Ley from Westrhauderfehn. She arrived in Lüneburg on 9 October 1941 and was one of the first children to be murdered.

Young people who did not behave in an appropriate manner and were considered »uneducable« were reported by the youth welfare service for admission to a »special children’s ward«. As a doctor at the Wunstorf youth welfare institution, Willi Baumert personally admitted his charges to the »special children’s ward« in Lüneburg. Siegfried Eilers, who came to Lüneburg with his three siblings, also had to go through this experience. His younger brother Ernst did not survive his stay there.

Ernst Eilers in the arms of his father Wilhelm Eilers, with his sister Hannelore standing to his left, Brünninghausen, around 1941.

Private property of Susanne Grünert.

Postcard of the Lüneburg Institution and Nursing Home, 1915.

ArEGL 99.

The postcard shows the Lüneburg Institution and Nursing Home, with the clubhouse (House 36) in the foreground. In the background, you can see houses 24, 23 and 25 (from left to right), which housed the Lüneburg »children’s ward«. There are at least 13 different postcards with different motifs and views of the grounds and individual buildings. Only this card shows all the buildings of the »children’s ward«.

The girls were housed on the upper floor of House 25, while the boys were housed on the ground floor. Another 20 boys were housed on the ground floor of House 23. In autumn 1944, the »children’s ward« moved out of House 23. The boys were transferred to House 25. From the beginning of 1945, House 25 was used as a military hospital. The »children’s ward« moved to House 24 and remained there until 1946.

House 25, 24 and House 23, after 1950.

ArEGL 109.

Excerpt from the transcript of the interrogation of nurse Marie-Luise Heusmann on 3 November 1947, p. 6.

NLA Hanover Lower Saxony 721 Lüneburg Acc. 8/98 No. 3.

Photo taken in a dormitory at the Lüneburg mental hospital after 1945. The furnishings were basic. Only the bare essentials were provided.

ArEGL 122.

There were large bedrooms with too few beds. Children had to share beds or lie on mattresses on the floor. There was not enough laundry and toiletries. Children who could not use the toilet were not washed adequately. They often did not receive clean clothes. Beds were rarely changed, and children lay in their own excrement. Due to poor hygiene and inadequate nutrition, skin and intestinal diseases spread.

When Elly Endewardt wanted to visit her son Jürgen three days after he was admitted, she was not allowed to see him. The mother entered the room anyway and saw a nurse hiding dirty bed linen under the bed. Apart from a duvet that was much too thin, she saw that Jürgen was completely naked despite the winter temperatures. Two weeks later, she visited twice more to speak to the medical director. The next day, Jürgen was dead.

Elly Endewardt with her three children Dieter, Jürgen and Ute (from left to right), summer 1942.

Private collection Barbara Burmester | Helga Endewardt.

Visitor index card for Jürgen Endewardt.

NLA Hanover Hann. 155 Lüneburg Acc. 56/83 No. 234.

Many parents complained that toys they had given their children disappeared. There was no school and no therapy. Nothing was done for the children and young people. Those young people who were »fit for work« had to help with gardening or field work. No one took care of the younger children until they were murdered.

List of medication consumption 1941–1948.

NLA Hanover Lower Saxony 721 Lüneburg Acc. 8/98 No. 3.

Paul Nitsche invented the »Luminal scheme« for the murder of children and adolescents. Excessive doses of the anti-epileptic drug Luminal, which was often prescribed as a sedative, were administered. When given over a longer period of time, this led to shallow breathing and caused respiratory diseases, circulatory and kidney failure. This allowed the murder of »lives unworthy of life« to be carried out in a seemingly natural and inconspicuous manner. In Lüneburg, Veronal and morphine were also used in addition to Luminal.

The consumption of drugs used for murder increased a hundredfold. The amount consumed remained high until 1947. This allows conclusions to be drawn.

The lives of children and young people depended on whether doctors assessed them as »capable of development« and »capable of education.« Poor development or low abilities were deemed »unworthy of life.« Even if extensive care was required, »treatment,« i.e., euthanasia, was considered. Doctors received so-called »authorisations« from the »Reich Committee.« Often, several were issued in a single day, as this list from Eglfing-Haar shows.

Excerpt from a list of authorisation cases from Major Leo Alexander’s report for the Nuremberg Doctors‘ Trial, in: Lutz Kälber: Kindermord in Nazi-Deutschland (Infanticide in Nazi Germany), in Gesellschaften 2, 2012.

Letter from the Reich Committee to Otto Wiepel dated 29 September 1942.

NLA Hanover Hann. 155 Lüneburg Acc. 56/83 No. 428

Otto Wiepel was assured by the »Reich Committee« that it would cover the costs of Herbert’s care for five months. That was the calculated life expectancy, because that was all the time the doctors and authorities had to carry out and administer Herbert’s murder.

Admission order from the »Reich Committee« for the admission of Lars Sundmäker to the »Children’s Ward« in Lüneburg, 8 April 1943.

NLA Hanover Hann. 155 Lüneburg Acc. 56/83 No. 405.

The »Reich Committee« determined admission to a »specialised children’s ward.« It also issued a »treatment recommendation.« Without having seen or met the children and adolescents, the experts Catel, Wentzler and Heinze marked the form with a red cross, a blue minus sign or a »B.« The Lüneburg »children’s ward« received a corresponding »treatment recommendation« in return. The cross meant murder, the »B« stood for »observation« and meant deferral, and the blue minus meant no murder.

There is no clear distinction between the crimes committed against adult patients and those committed against adolescents or minors. Adolescents aged 14 and above who were housed in the »children’s ward« were reported for sterilisation and forcibly sterilised. They were also transferred to killing centres and youth concentration camps, where they were subjected to physical violence and even murder. The children and adolescents housed in Lüneburg were only spared from being transferred to youth concentration camps.

Applications for sterilisation by Max Bräuner and Hans Rohlfing from August 1942.

NLA Hanover Hann. 138 Lüneburg Acc. 103/88 No. 609.

For Ingeborg Wernitz, sterilisation was a mandatory requirement for her to be discharged from the »children’s ward«. The application was submitted four months before her 14th birthday. She was forcibly sterilised on 21 January 1943 and only discharged afterwards.

On 8 September 1943, at least eleven young people under the age of 18 were transferred from the Lüneburg institution and nursing home to the Pfafferode killing centre. Eight of them were murdered there; only one was released before the end of the war. One young woman survived, but was transferred back to Lüneburg in 1947.

The young people murdered in Pfafferode are:

Ilse Allrütz (1928 – 1944)

Richard Bergmann (1926 – 1943)

Rolf Erbguth (1928 – 1943)

Harald Frandsen (1926 – 1944)

Kurt Nolte (1925 – 1944)

Gerda Plenge (1927 – 1945)

Otto Schulz (1927 – 1944)

Ekatharina Taranowa (1926 – 1944)

»EUTANAZJA DZIECI«

Od 1940 r. pierwsze »oddziały dziecięce« zaczęły działać w Görden, Dösen, Marsbergu i Wiedniu (»Spiegelgrund«). Ponieważ wymóg zgłaszania dzieci rzadko był przestrzegany, a rodzice wykazywali niewielką chęć do współpracy, Ministerstwo Spraw Wewnętrznych Rzeszy wydało dekret. Między innymi podwyższono wiek dzieci podlegających zgłoszeniu do 16 lat. W rezultacie utworzono kolejne »specjalne oddziały dziecięce«, a liczba morderstw dzieci wzrosła. »Specjalny oddział dziecięcy« w Lüneburgu rozpoczął działalność i stał się jednym z głównych miejsc zbrodni.

Fragment dekretu Ministerstwa Spraw Wewnętrznych Rzeszy z dnia 20 września 1941 r.

NLA Hanower Nds. 721 Lüneburg Acc. 8/98 n. 3/9.

Właściwe władze otrzymały wyraźne polecenie wypełnienia swoich obowiązków sprawozdawczych. Miały one przekonać rodziców, że środek ten jest korzystny dla społeczności i rodzin. Najwyraźniej wyniki ankiety przeprowadzonej przez Ewalda Meltzera w 1920 r. nie były dokładne. Badanie, które zostało opublikowane dopiero w 1925 r., wykazało, że 78 procent rodziców chciało, aby ich niepełnosprawne dzieci zostały »uratowane«. Jednak nie była to prawda.

Zarejestrowane dzieci i młodzież były badane przez »Komisję Rzeszy« i lokalnych lekarzy. Ocena, czy dziecko lub nastolatek był »zdolny do rozwoju i edukacji«, decydowała o tym, czy przeżyje, czy umrze. Osoby uznane za »niezdolne« były mordowane, a ich mózgi wykorzystywano do badań medycznych.

W domach, szpitalach i instytucjach utworzono ponad 30 »oddziałów dziecięcych« w celu przeprowadzania »eutanazji dzieci«. Nie wszystkie z nich funkcjonowały w tym samym okresie. Wiadomo, że na »oddziałach dziecięcych« zmarło około 6800 dzieci i nastolatków, z czego co najmniej 6500 zostało zamordowanych.

Nawet poza »oddziałami dziecięcymi« w wielu miejscach dochodziło do »eutanazji dzieci« na nieznaną skalę.

Akt zgonu z dnia 13 września 1941 r.

Archiwum Państwowe w Hamburgu 352-8/7 Szpital Państwowy Langenhorn n. 86294.

Przed utworzeniem »oddziału dziecięcego« w Lüneburgu co najmniej dziesięcioro dzieci z przyszłego obszaru działania zostało przyjętych do dwóch »oddziałów dziecięcych« w Hamburgu, Rothenburgsort (1) i Langenhorn (9):

- Hermann Beekhuis (Leer)

- Helmuth Beneke (Bremervörde)

- Gerda Cordes (Uelzen)

- Marianne Harms (Bardowick)

- Hillene Hellmers (Leer)

- Irmgard Jagemann (Bremen)

- Rosemarie Kablitz (Wilstedt)

- Edda Purwin (Lüneburg)

- Günther Schindler (Wilhelmshaven)

- Hans-Ludwig Würflinger (Bremen)

Pięciu z nich powróciło do domu w latach 1942–1943, pozostali zostali zamordowani. Najmłodszą ofiarą był Hermann Beekhuis. Został zamordowany w wieku trzech i pół miesiąca w szpitalu dziecięcym w Rothenburgsort. Oficjalna data śmierci została sfałszowana.

Fragment przesłuchania Friedy Bergmann z dnia 5 listopada 1947 r.

NLA Hanower Dolna Saksonia 721 Lüneburg Acc. 8/98 n. 3.

W dniach 9 i 10 października 1941 r. do »oddziału dziecięcego« w budynkach 25 i 23 szpitala psychiatrycznego w Lüneburgu przyjęto 138 dzieci i młodzieży. Pochodziły one z instytucji Rotenburga należących do Inner Mission. Z tej pierwszej grupy przeżyło tylko dziewięciu chłopców i siedem dziewcząt. Frieda Bergmann, pielęgniarka z »oddziału dziecięcego« w Lüneburgu, została przesłuchana w Lüneburgu wkrótce po wojnie.

Widok z lotu ptaka na instytucje Misji Wewnętrznej w Rotenburgu, pocztówka, przed 1945 r.

ArEGL 99.

Instytucje Inner Mission w Rotenburgu miały służyć jako szpital pomocniczy dla ofiar wojny powietrznej w Bremie. W tym celu zamknięto oddział dziecięcy, a dzieci tam leczone zostały rozdzielone. Dziewięćdziesiąt dziewięć dzieci wysłano do instytucji von Bodelschwingh w Bethel w Bielefeldzie, a 24 dzieci wysłano do Fundacji Eben-Ezer w Lemgo. Dzieci, które nie mogły uczęszczać do szkoły, przeniesiono do »oddziału dziecięcego« w Lüneburgu.

Dla wielu dzieci i młodzieży niepełnosprawnej z prowincji Hanower instytucje Inner Mission w Rotenburgu były wielkim domem. Na przedstawionych tutaj zdjęciach z pewnością znajdują się dzieci i młodzież, które później zamordowano w Lüneburgu. Na zdjęciu chłopców przed Wichernhausem po lewej stronie widać na przykład Eckarta Willumeita z Celle.

Młodzi ludzie z bratem Karlem Stallbaumem przed budynkiem Wichernhaus należącym do organizacji Rotenburg Works of the Inner Mission, około 1938 roku. Autor zdjęcia: Kurt Stallbaum.

Archiwum dzieł wewnętrznej misji w Rotenburgu.

Zdjęcie grupowe dzieci przewożonych z Hanoweru-Langenhagen. Po lewej stronie stoi dyrektor z Rotenburga, pastor Johannes Buhrfeind. Za nim po prawej stronie stoi pielęgniarz oddziałowy lub »ojciec domu« Grützmacher.

Archiwum dzieł wewnętrznej misji w Rotenburgu.

Wśród dzieci przeniesionych do Lüneburga było 25, które 18 marca 1938 r. przeniesiono ze szpitala psychiatrycznego w Hanowerze-Langenhagen do Rotenburga po zamknięciu kliniki dziecięcej w Langenhagen. Oprócz Eckarta Willumeita byli to Friedrich Daps, Waldemar Borcholte i Hans-Herbert Niehoff. Muszą to być cztery dzieci widoczne na zdjęciu.

W okresie od 1941 r. do 24 sierpnia 1945 r. do »oddziału dziecięcego« w Lüneburgu przyjęto łącznie co najmniej 762 dzieci i młodzież w wieku od jednego dnia do 16 lat. Ponad 440 z nich nie przeżyło pobytu w szpitalu. Nie jest jasne, czy kolejne 61 dzieci i młodzieży przeżyło.

Śmiertelność na »oddziale dziecięcym« w Lüneburgu wyniosła ponad 60 procent. Ponieważ nie wszystkie losy są znane, może być ona nawet wyższa.

Większość dzieci i młodzieży zamordowano w 1943 r. (132) i 1944 r. (120). Nawet po zakończeniu wojny nadal dochodziło do zgonów. Ostatnia hospitalizacja na »oddziale dziecięcym« w Lüneburgu miała miejsce 23 sierpnia 1945 roku. Pacjentem był półtoraroczny Heiko Bromm z Hannoversch-Münden. Zmarł dwa miesiące później.

To, czy i ile dzieci i młodzieży zostało skierowanych na »oddział dziecięcy«, zależało od działań rodziców, położnych, nauczycieli i władz zdrowotnych. Działania te różniły się znacznie w zależności od regionu. Były regiony, z których nie zgłoszono żadnego dziecka lub zgłoszono tylko jedno dziecko (np. Cloppenburg i Vechta). Znaczna liczba dzieci została przyjęta na »oddział dziecięcy« z Hanoweru (135), Bremy (39), Celle (33), Lüneburga (33), Bremerhaven (31) i Hildesheim (31).

Dzieci i młodzież przebywające na »oddziale dziecięcym« w Lüneburgu pochodziły z terenów dzisiejszych krajów związkowych Dolna Saksonia, Brema, Hamburg i Nadrenia Północna-Westfalia. Ta mapa obszaru, z którego pochodzili pacjenci, pokazuje miasta i powiaty, z których zostali przyjęci na »oddział dziecięcy« w Lüneburgu, oraz liczbę tych osób.

Herta Ley, około wiosny 1932 roku.

ArEGL.

Władze sanitarne w Leer miały kilku bardzo oddanych pracowników. Osiem z trzynastu dzieci z Leer zostało zamordowanych. Wśród nich była Herta Ley z Westrhauderfehn. Przybyła do Lüneburga 9 października 1941 roku i była jedną z pierwszych zamordowanych dzieci.

Młodzi ludzie, którzy nie zachowywali się w odpowiedni sposób i byli uznawani za »niezdolnych do wychowania«, byli zgłaszani przez służbę pomocy społecznej dla młodzieży do przyjęcia na »specjalny oddział dziecięcy«. Jako lekarz w instytucji pomocy społecznej dla młodzieży w Wunstorfie, Willi Baumert osobiście przyjmował swoich podopiecznych na »specjalny oddział dziecięcy« w Lüneburgu. Siegfried Eilers, który przybył do Lüneburga wraz z trójką rodzeństwa, również musiał przejść przez to doświadczenie. Jego młodszy brat Ernst nie przeżył pobytu w tym miejscu.

Ernst Eilers w ramionach swojego ojca Wilhelma Eilersa, z siostrą Hannelore stojącą po jego lewej stronie, Brünninghausen, około 1941 roku.

Własność prywatna Susanne Grünert.

Pocztówka przedstawiająca zakład opiekuńczy i dom spokojnej starości w Lüneburgu, 1915 r.

ArEGL 99.

Pocztówka przedstawia zakład opiekuńczy i dom spokojnej starości w Lüneburgu, z klubem (dom nr 36) na pierwszym planie. W tle widać domy 24, 23 i 25 (od lewej do prawej), w których mieścił się »oddział dziecięcy« w Lüneburgu. Istnieje co najmniej 13 różnych pocztówek z różnymi motywami i widokami terenu oraz poszczególnych budynków. Tylko ta pocztówka przedstawia wszystkie budynki »oddziału dziecięcego«.

Dziewczęta były zakwaterowane na piętrze budynku nr 25, natomiast chłopcy na parterze. Kolejnych 20 chłopców zakwaterowano na parterze budynku nr 23. Jesienią 1944 r. »oddział dziecięcy« wyprowadził się z budynku nr 23. Chłopcy zostali przeniesieni do budynku nr 25. Od początku 1945 r. budynek nr 25 służył jako szpital wojskowy. »Oddział dziecięcy« przeniósł się do budynku nr 24 i pozostał tam do 1946 r.

Dom 25, 24 i dom 23, po 1950 roku.

ArEGL 109.

Fragment protokołu przesłuchania pielęgniarki Marie-Luise Heusmann z dnia 3 listopada 1947 r., str. 6.

NLA Hanower Dolna Saksonia 721 Lüneburg Acc. 8/98 n. 3.

Zdjęcie wykonane w dormitorium szpitala psychiatrycznego w Lüneburgu po 1945 roku. Wyposażenie było bardzo skromne. Zapewniono jedynie najpotrzebniejsze rzeczy.

ArEGL 122.

Były tam duże sypialnie z zbyt małą liczbą łóżek. Dzieci musiały dzielić łóżka lub spać na materacach rozłożonych na podłodze. Brakowało środków do prania i artykułów toaletowych. Dzieci, które nie potrafiły korzystać z toalety, nie były odpowiednio myte. Często nie otrzymywały czystej odzieży. Łóżka rzadko były zmieniane, a dzieci leżały we własnych odchodach. Z powodu złych warunków higienicznych i nieodpowiedniego odżywiania rozprzestrzeniały się choroby skóry i jelit.

Kiedy Elly Endewardt chciała odwiedzić swojego syna Jürgena trzy dni po jego przyjęciu do szpitala, nie pozwolono jej się z nim zobaczyć. Matka mimo to weszła do pokoju i zobaczyła pielęgniarkę chowającą brudną pościel pod łóżkiem. Oprócz zbyt cienkiej kołdry zauważyła, że Jürgen był całkowicie nagi, mimo zimowych temperatur. Dwa tygodnie później odwiedziła szpital jeszcze dwa razy, aby porozmawiać z dyrektorem medycznym. Następnego dnia Jürgen nie żył.

Elly Endewardt z trójką dzieci: Dieterem, Jürgenem i Ute (od lewej do prawej), lato 1942 roku.

Prywatna kolekcja Barbary Burmester | Helga Endewardt.

Karta odwiedzającego dla Jürgena Endewardta.

NLA Hanower Hann. 155 Lüneburg Acc. 56/83 n. 234.

Wielu rodziców skarżyło się, że zabawki, które dali swoim dzieciom, zniknęły. Nie było szkoły ani terapii. Nie zrobiono nic dla dzieci i młodzieży. Młodzi ludzie, którzy byli »zdolni do pracy«, musieli pomagać w pracach ogrodniczych lub polowych. Nikt nie opiekował się młodszymi dziećmi, dopóki nie zostały zamordowane.

Wykaz zużycia leków w latach 1941–1948.

NLA Hanower Dolna Saksonia 721 Lüneburg Acc. 8/98 n. 3.

Paul Nitsche opracował »schemat Luminal« służący do zabijania dzieci i młodzieży. Podawano nadmierne dawki leku przeciwpadaczkowego Luminal, który często był przepisywany jako środek uspokajający. Podawanie tego leku przez dłuższy czas prowadziło do płytkiego oddychania i powodowało choroby układu oddechowego, niewydolność krążenia i niewydolność nerek. Pozwalało to na zabijanie »niegodnych życia« w sposób pozornie naturalny i nie rzucający się w oczy. W Lüneburgu oprócz Luminalu stosowano również Veronal i morfinę.

Zużycie leków wykorzystywanych do popełniania morderstw wzrosło stukrotnie. Ilość zużytych leków pozostawała wysoka aż do 1947 roku. Pozwala to wyciągnąć pewne wnioski.

Losy dzieci i młodzieży zależały od tego, czy lekarze ocenili je jako »zdolne do rozwoju« i »zdolne do nauki«. Słaby rozwój lub niskie zdolności uznawano za »niegodne życia«. Nawet jeśli wymagana była intensywna opieka, rozważano »leczenie«, czyli eutanazję. Lekarze otrzymywali tak zwane »zezwolenia« od »Komisji Rzeszy«. Często wydawano kilka takich zezwoleń w ciągu jednego dnia, jak pokazuje ta lista z Eglfing-Haar.

Fragment wykazu przypadków udzielenia zezwolenia z raportu majora Leo Alexandra dla procesu lekarzy w Norymberdze, w: Lutz Kälber: Kindermord in Nazi-Deutschland (Dzieciobójstwo w nazistowskich Niemczech), w Gesellschaften 2, 2012.

List Komitetu Rzeszy do Otto Wiepela z dnia 29 września 1942 r.

NLA Hanower Hann. 155 Lüneburg Acc. 56/83 n. 428

Otto Wiepel otrzymał od »Komisji Rzeszy« zapewnienie, że pokryje ona koszty opieki nad Herbertem przez pięć miesięcy. Była to obliczona długość życia, ponieważ tyle czasu mieli lekarze i władze na przeprowadzenie i zorganizowanie morderstwa Herberta.

Postanowienie »Komisji Rzeszy« o przyjęciu Larsa Sundmäkera do »oddziału dziecięcego« w Lüneburgu, 8 kwietnia 1943 r.

NLA Hanower Hann. 155 Lüneburg Acc. 56/83 n. 405.

»Komisja Rzeszy« podjęła decyzję o przyjęciu dzieci do »specjalistycznego oddziału dziecięcego«. Wydała również »zalecenie dotyczące leczenia«. Nie widząc ani nie spotykając się z dziećmi i młodzieżą, eksperci Catel, Wentzler i Heinze zaznaczyli na formularzu czerwony krzyżyk, niebieski znak minus lub literę »B«. Oddział dziecięcy w Lüneburgu otrzymał w zamian odpowiednie »zalecenie dotyczące leczenia«. Krzyżyk oznaczał zabójstwo, litera »B« oznaczała »obserwację« i oznaczała odroczenie, a niebieski znak minus oznaczał brak zabójstwa.

Nie ma wyraźnego rozróżnienia między przestępstwami popełnionymi wobec dorosłych pacjentów a przestępstwami popełnionymi wobec nastolatków lub nieletnich. Nastolatki w wieku 14 lat i starsze, które były umieszczone na »oddziale dziecięcym«, były zgłaszane do sterylizacji i poddawane przymusowej sterylizacji. Były one również przenoszone do ośrodków zagłady i obozów koncentracyjnych dla młodzieży, gdzie poddawano je przemocy fizycznej, a nawet mordowano. Dzieci i nastolatki umieszczone w Lüneburgu uniknęły jedynie przeniesienia do obozów koncentracyjnych dla młodzieży.

Wnioski o sterylizację złożone przez Maxa Bräunera i Hansa Rohlfinga w sierpniu 1942 r.

NLA Hanower Hann. 138 Lüneburg Acc. 103/88 n. 609.

Dla Ingeborg Wernitz sterylizacja była warunkiem koniecznym do wypisania jej z »oddziału dziecięcego«. Wniosek złożono cztery miesiące przed jej 14. urodzinami. Została poddana przymusowej sterylizacji 21 stycznia 1943 r. i dopiero potem została wypisana ze szpitala.

8 września 1943 r. co najmniej jedenaście młodych osób poniżej 18 roku życia zostało przeniesionych z zakładu opiekuńczego i domu spokojnej starości w Lüneburgu do ośrodka zagłady w Pfafferode. Osiem z nich zostało tam zamordowanych; tylko jedna osoba została zwolniona przed końcem wojny. Jedna młoda kobieta przeżyła, ale w 1947 r. została przeniesiona z powrotem do Lüneburga.

Młodzi ludzie zamordowani w Pfafferode to:

Ilse Allrütz (1928 – 1944)

Richard Bergmann (1926 – 1943)

Rolf Erbguth (1928 – 1943)

Harald Frandsen (1926 – 1944)

Kurt Nolte (1925 – 1944)

Gerda Plenge (1927 – 1945)

Otto Schulz (1927 – 1944)

Ekatharina Taranowa (1926 – 1944)