NFC zu H-P-02-1

»AKTION T4«

Im Rahmen der »Aktion T4« sollten Erkrankte ermordet werden, die länger als fünf Jahre in einer Anstalt waren, als nicht arbeitsfähig galten und wenig Kontakt zu Angehörigen hatten. Aus Lüneburg wurden 483 Erkrankte verlegt, auch ohne diese Anforderungen zu erfüllen. 479 von ihnen wurden ermordet. Alle wurden mit Kohlenmonoxid erstickt. Der Mord blieb nicht geheim und es gab Widerspruch vom Justizministerium, von Familien und der katholischen Kirche. Im August 1941 stoppten die Nationalsozialisten die »Aktion T4« offiziell.

AKTION T4

Die Nazis ermorden viele Kranke.

Sie haben dafür einen extra Namen.

Sie nennen das: Aktion T4.

T4 ist kurz für: Tiergartenstraße 4.

Das ist eine Adresse in Berlin.

Dort planen die Nazis den Kranken-Mord.

Der Kranken-Mord passiert

in besonderen Anstalten.

Das sind Tötungs-Anstalten.

Dort ermordet man die Kranken

in Gas-Kammern.

Die Kranken ersticken an Gas.

Die Nazis ermorden Kranke,

• die länger als 5 Jahre krank sind.

• die nicht arbeiten können.

• die keine Familie haben.

• um die sich keiner kümmert.

• die jüdisch sind.

• die kriminell sind.

Die katholische Kirche und die Familien sind gegen den Kranken-Mord.

Auch das Ministerium für Recht ist dagegen.

Sie sagen: Der Kranken-Mord ist falsch.

Im August 1941 sagen die Nazis sie beenden die Aktion T4.

Aber sie machen heimlich weiter

mit der Aktion T4.

Alle Erkrankten fuhren mit Zügen vom Lüneburger Bahnhof in die Anstalten der »Aktion T4« ab. Bahnhof Lüneburg, 1939.

StadtALg, BS, Pos-19249.

Abtransport von Patienten der Anstalt Liebenau, August 1940.

Stiftung Liebenau.

Die Verlegungen der 483 Lüneburger Erkrankten in die Tötungsanstalten Brandenburg und Pirna-Sonnenstein sowie in die Zwischenanstalt Herborn fanden mit Personenzügen statt. Nur bei der Verlegung von der Zwischenanstalt Herborn in die Tötungsanstalt Hadamar wurden Reichspostbusse eingesetzt.

483 Kranke aus Lüneburg kommen

in Tötungs-Anstalten

• nach Brandenburg in Brandenburg,

• nach Pirna-Sonnenstein in Sachsen und

• nach Hadamar in Hessen.

Die Tötungs-Anstalten sind weit weg.

Man bringt die Kranken mit dem Zug

dort hin.

Einige Kranke kommen in die Anstalt

nach Hadamar.

Vorher kommen sie in eine Zwischenanstalt in Herborn.

Dort sind sie ein paar Wochen.

Dann bringt man die Kranken

mit roten Bussen nach Hadamar.

Die roten Busse gehören der Post.

Die Post hilft den Nazis dabei,

die Kranken in die Tötungs-Anstalt zu bringen.

Auf dem ersten Foto sieht man den Bahnhof

in Lüneburg im Jahr 1941.

Auf dem zweiten Foto sieht man

einen roten Bus.

Mit diesen Bussen bringt man Kranke

in die Tötungs-Anstalt.

»Mit Bouhler Frage der stillschweigenden Liquidierung von Geisteskranken besprochen. 80000 sind weg, 60000 müssen noch weg. Das ist eine harte, aber auch eine notwendige Arbeit. Und sie muß jetzt getan werden. Bouhler ist der rechte Mann dazu.«

Tagebucheintrag von Joseph Goebbels vom 22. Februar 1941. Zitiert nach Ralf Georg Reuth (Hg.): Joseph Goebbels Tagebücher 1924 – 1945, hier Bd. 4 1940 – 1942, München 1992.

Joseph Goebbels

ist ein sehr wichtiger Nazi.

Er schreibt in sein Tagebuch:

80.000 Kranke haben wir schon ermordet.

60.000 Kranke müssen wir noch ermorden .

Das ist schwere Arbeit.

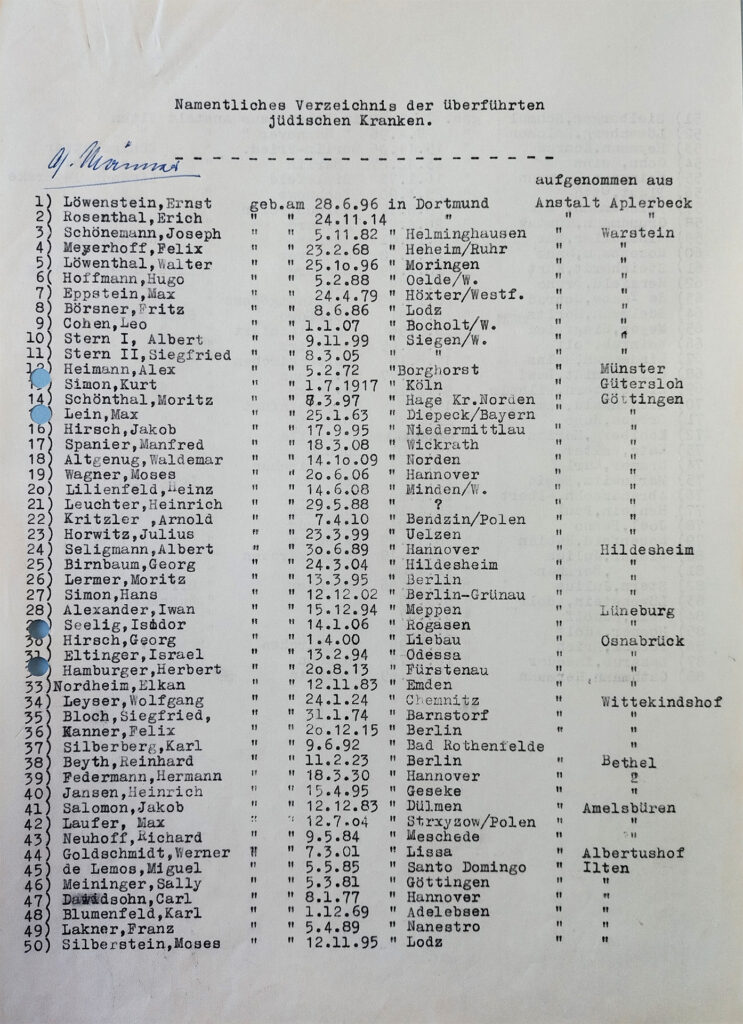

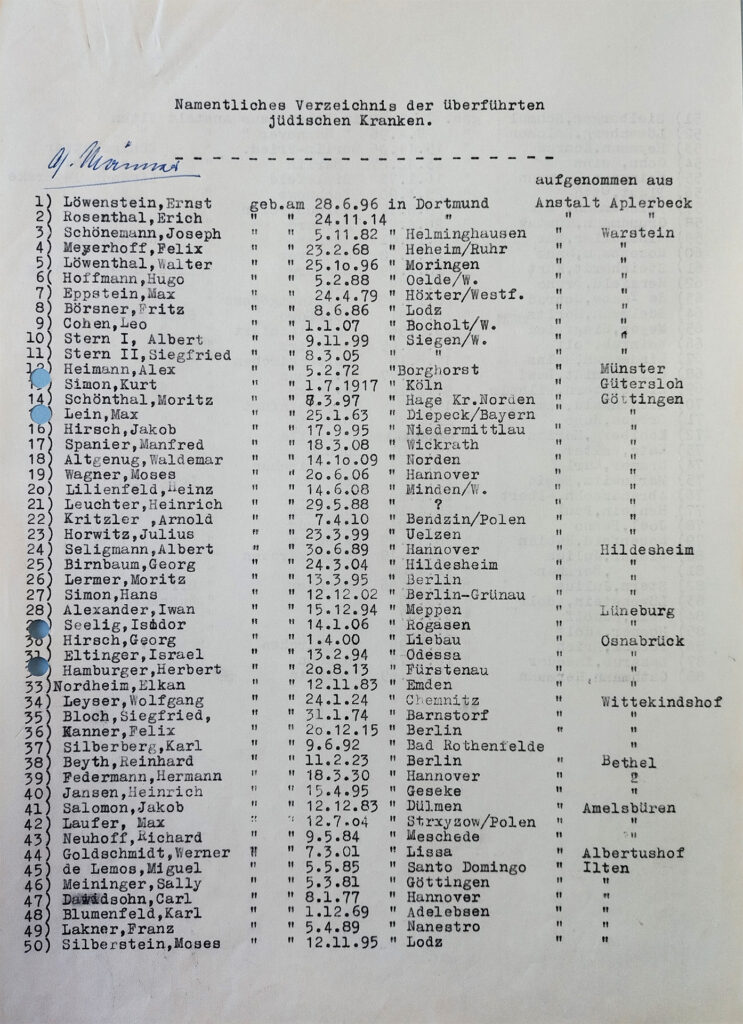

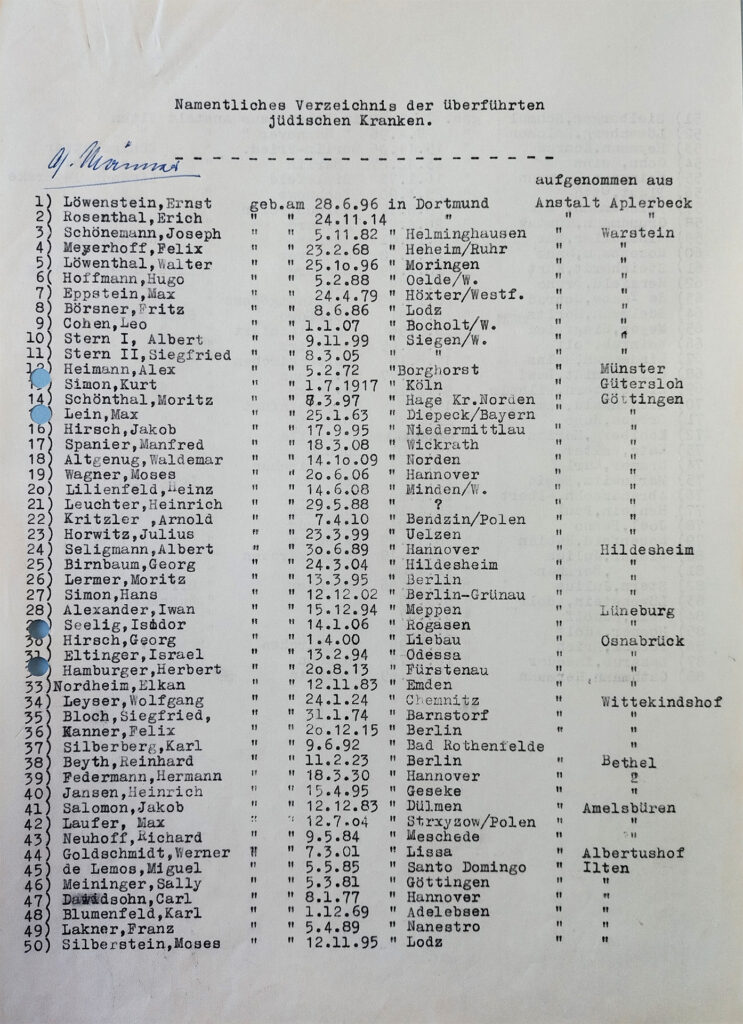

150 jüdische Erkrankte aus insgesamt 25 Einrichtungen, unter ihnen Isidor Seelig und Iwan Alexander, wurden im September 1940 aus den Provinzen Hannover und Westfalen in die Heil- und Pflegeanstalt Wunstorf überwiesen. Acht jüdische Erkrankte waren schon in Wunstorf untergebracht. Am 27. September 1940 wurden somit insgesamt 158 jüdische Erkrankte von Wunstorf in die Tötungsanstalt Brandenburg verlegt und dort mit Gas ermordet.

Im Jahr 1940 bringen die Nazis

150 jüdische Kranke in die Anstalt nach Wunstorf.

8 Juden sind schon vorher in Wunstorf.

Die 150 jüdischen Kranken kommen aus anderen Anstalten aus Deutschland nach Wunstorf.

Auch 2 jüdische Kranke aus Lüneburg kommen nach Wunstorf:

Isidor Seelig und Iwan Alexander.

Sie müssen nach Wunstorf, weil sie Juden sind.

Die jüdischen Kranken sind

nur ganz kurz in Wunstorf.

Nach wenigen Tagen bringt man alle Juden weg.

Sie kommen in die Tötungs-Anstalt

nach Brandenburg an der Havel.

Die Nazis ermorden die Juden dort mit Gas.

In Brandenburg ermorden die Nazis 158 jüdische Kranke aus der Anstalt Wunsdorf.

Auszug aus dem Namentlichen Verzeichnis der überführten jüdischen Kranken, September 1940.

NLA Hannover Hann. 155 Wunstorf Acc. 38/84 Nr. 10.

»Ich bemerke noch, dass die Unterbringung der Kranken in

Wunstorf in einfachster Form (Strohschütte ohne Strohsäcke) in dem kürzlich vom Militär geräumten, bisher als Reservelazarett benutzten Teil der Anstalt sichergestellt ist.«

Oberpräsident der Provinz Hannover an den Reichsminister des Innern. Zitiert nach: Asmus Finzen: Massenmord ohne Schuldgefühl, Bonn 1996.

Man behandelt die Kranken in Wunstorf schlecht.

Die Kranken haben keine Betten.

Sie schlafen auf dem Fußboden auf Stroh.

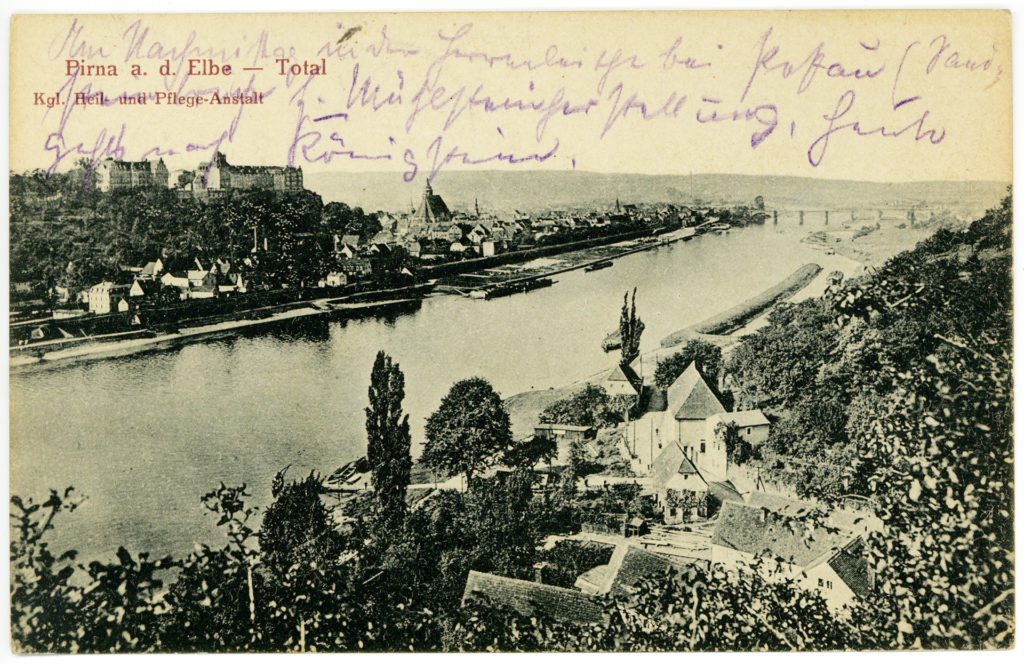

Am 7. März 1941 wurden 122 Erkrankte im Rahmen der »Aktion T4« aus Lüneburg in die Tötungsanstalt Pirna-Sonnenstein verlegt. Sie wurden von Personal der Berliner »T4-Zentrale« begleitet. Sie reisten mit dem Zug. Hierfür mussten sie zu Fuß zum Lüneburger Bahnhof laufen. Dort wurden zwei Waggons an einen Personenzug angehängt. Die Erkrankten wurden direkt nach Pirna (Sachsen) gebracht und mussten nach der Ankunft erneut zu Fuß vom Bahnhof zur Tötungsanstalt laufen.

Am 7. März 1941 bringen die Nazis

122 Kranke aus Lüneburg in eine Tötungs-Anstalt.

Die Tötungs-Anstalt ist in Pirna-Sonnenstein.

Die Kranken sollen dort

mit Gas ermordet werden.

Die Nazis nennen das: Aktion T4.

Die 122 Kranken laufen von der Anstalt

zum Bahnhof.

Dann fahren sie mit dem Zug von Lüneburg nach Pirna-Sonnenstein.

In Pirna-Sonnenstein laufen die Kranken

vom Bahnhof zur Tötungs-Anstalt.

Die ganze Zeit sind Pfleger bei den Kranken.

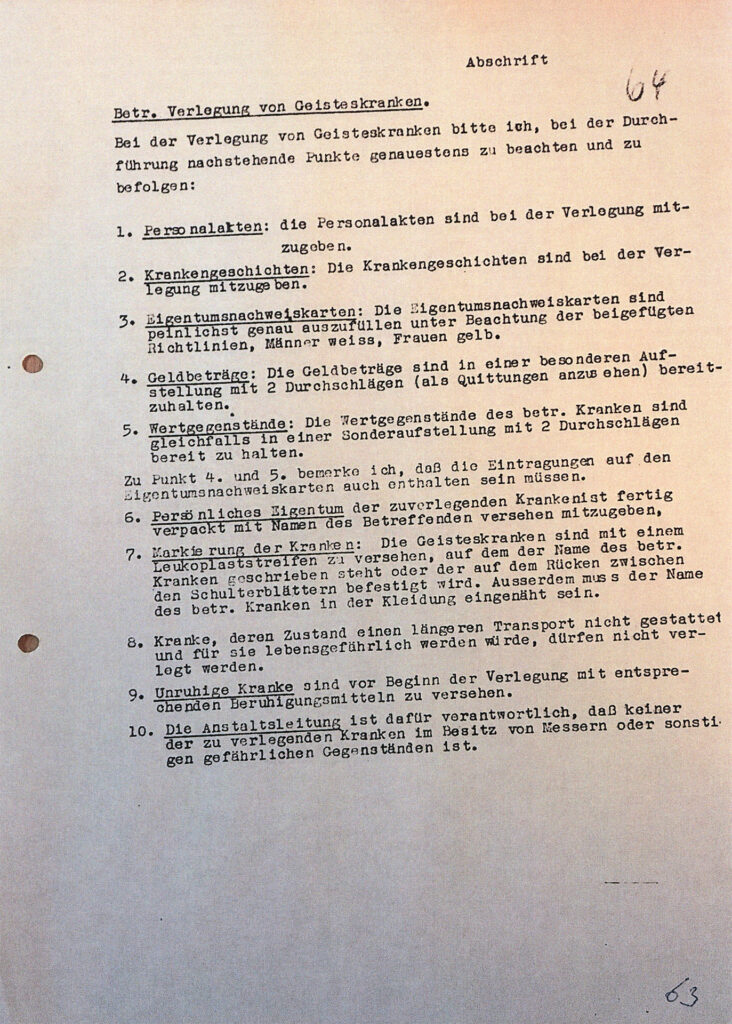

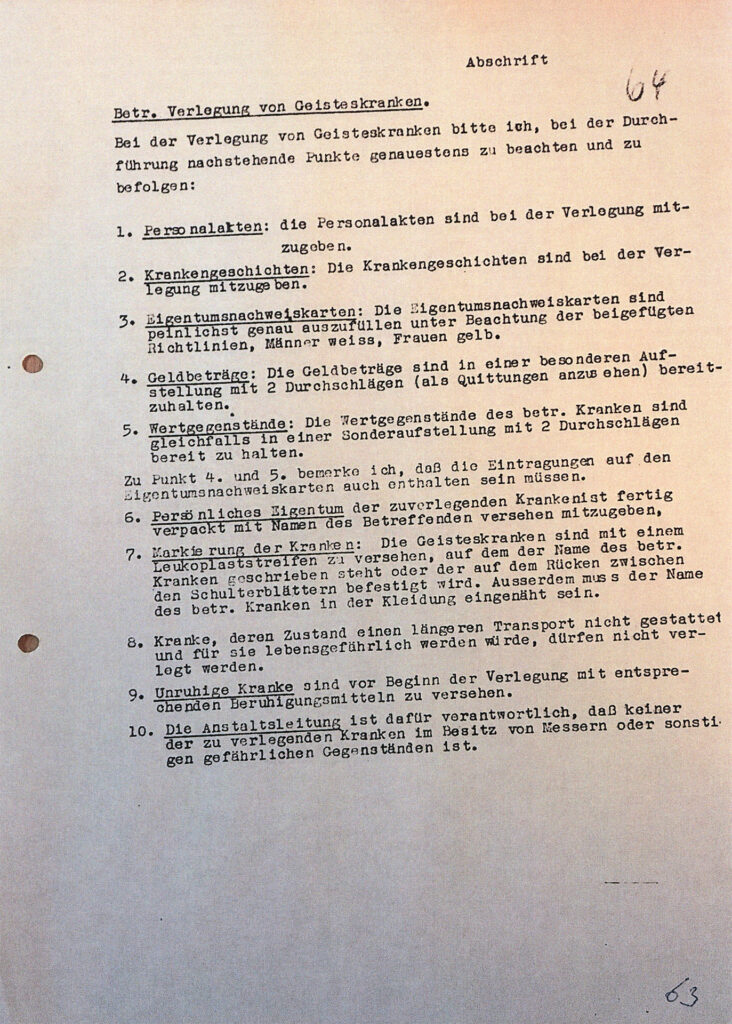

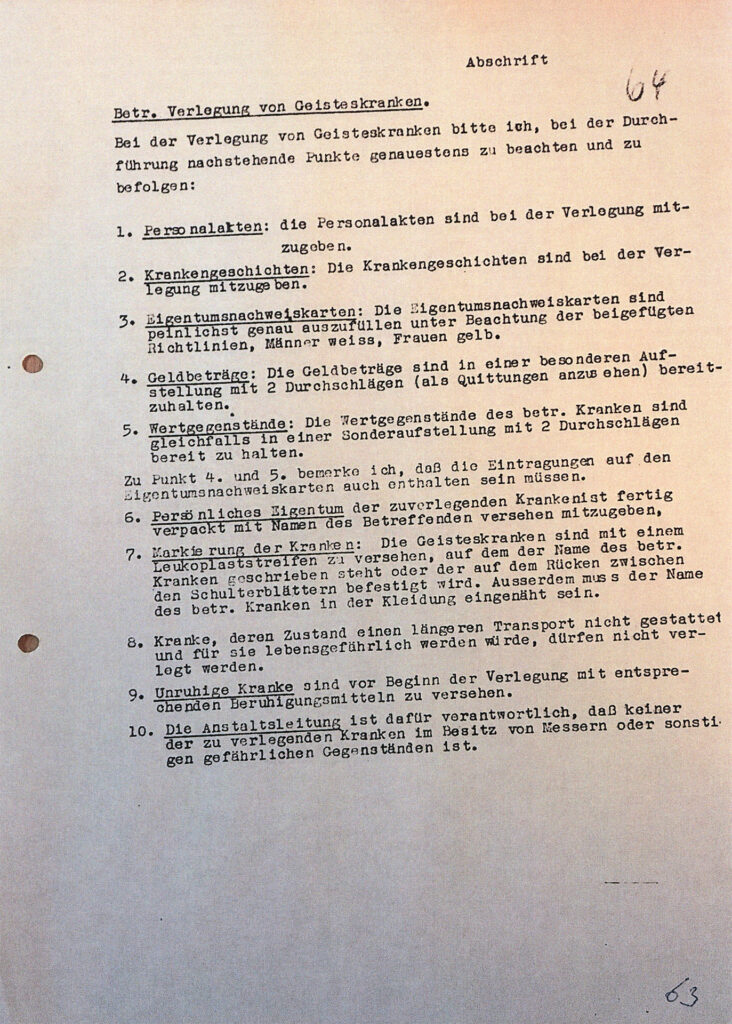

Vermerk: Betr. Verlegung von Geisteskranken, etwa 1940.

Kopie ArEGL.

Diese Vorgaben mussten bei der Verlegung erfüllt werden.

Die Nazis bringen Kranke aus Anstalten

in Tötungs-Anstalten.

Das heißt: Verlegung.

Die Nazis haben für eine Verlegung feste Regeln.

Zum Beispiel:

• Welche Unterlagen müssen

die Kranken mitbringen?

• Was passiert mit den Sachen

von den Kranken?

• Wie müssen die Kranken ihren Namen an der Kleidung tragen?

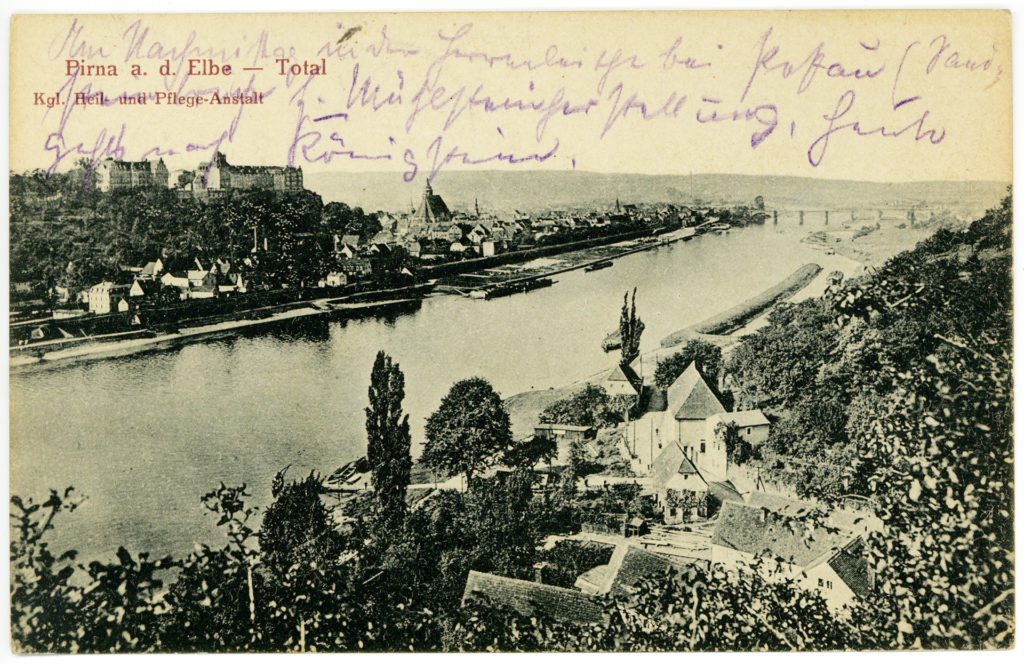

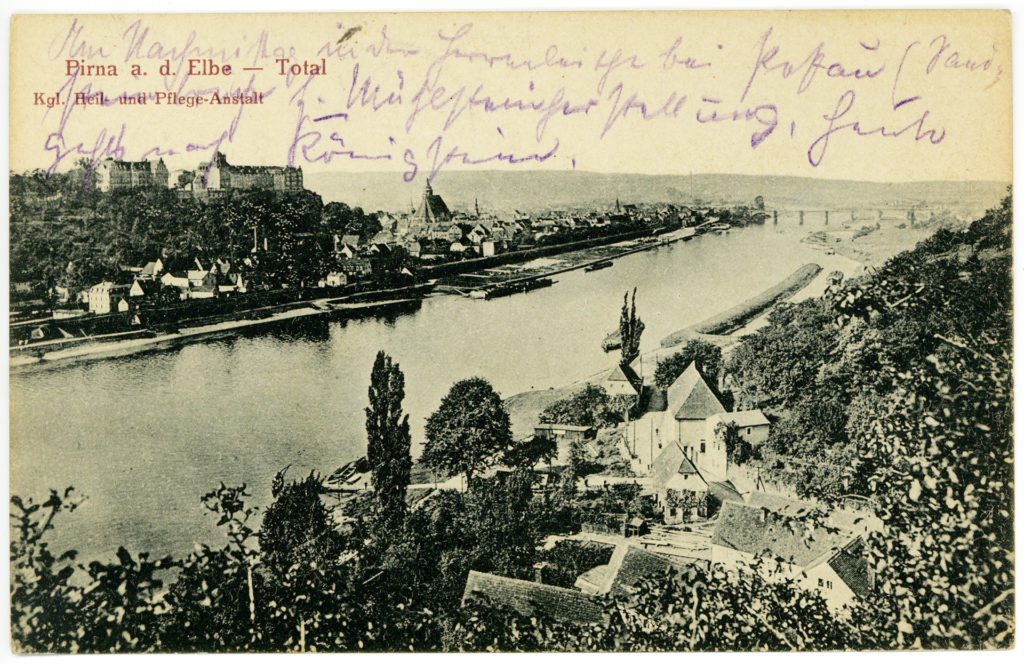

Nach Ankunft in der Anstalt Pirna-Sonnenstein wurden die Erkrankten untersucht und in einen Umkleideraum geführt. Sie mussten sich ausziehen. Von dort gelangten sie in die Gaskammer. Hinter der Gaskammer waren zwei Öfen, in denen die Ermordeten eingeäschert wurden. Leichenbrenner kippten die Asche einfach auf den Elbhang hinter der Anstalt.

Die Kranken kommen in der Tötungs-Anstalt Pirna-Sonnenstein an.

Dann sagt man den Kranken:

Zuerst gibt es eine Untersuchung.

Darum gehen die Kranken in eine Umkleide.

Dort ziehen sie sich aus.

Dann bringen die Nazis die Kranken

in eine Gas-Kammer.

In die Gas-Kammer fließt Gas.

Die Kranken atmen das Gas ein und ersticken.

Sie sterben in der Gas-Kammer.

Hinter der Gas-Kammer sind 2 Öfen.

Man verbrennt die toten Körper

von den Kranken in den Öfen.

Es bleibt nur Asche übrig von den Kranken.

Die Nazis kippen die Asche

auf einen Hang hinter der Anstalt.

Unter dem Hang fließt ein Fluss.

Man sieht den Fluss auf dieser Postkarte

aus dem Jahr 1923.

Postkarte, Pirna mit Schloss Sonnenstein (links oben), 1923.

ArEGL 99.

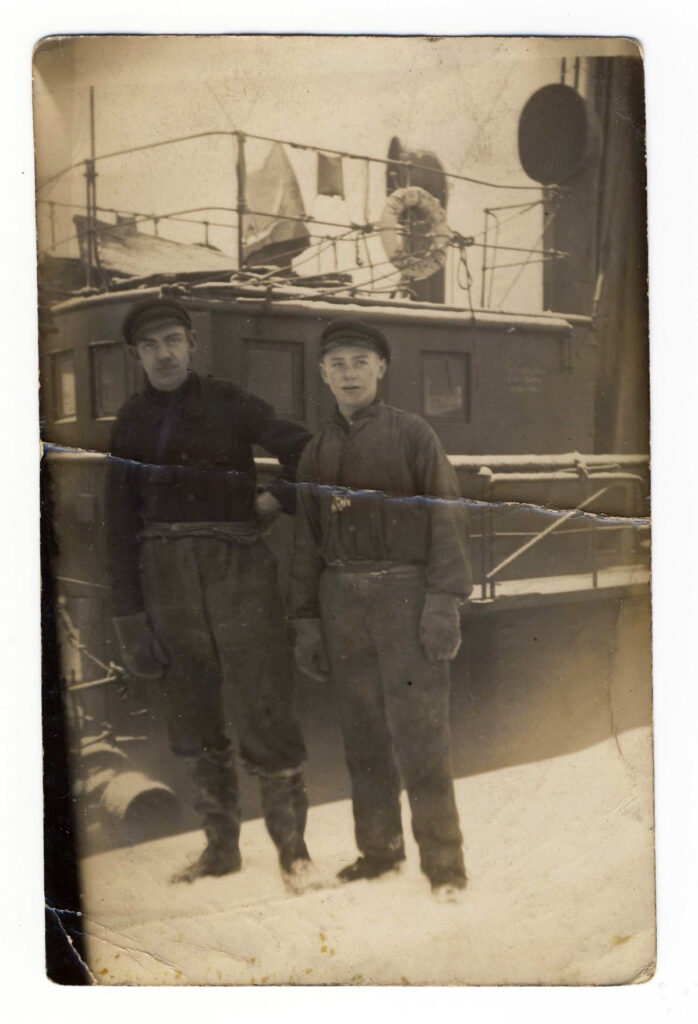

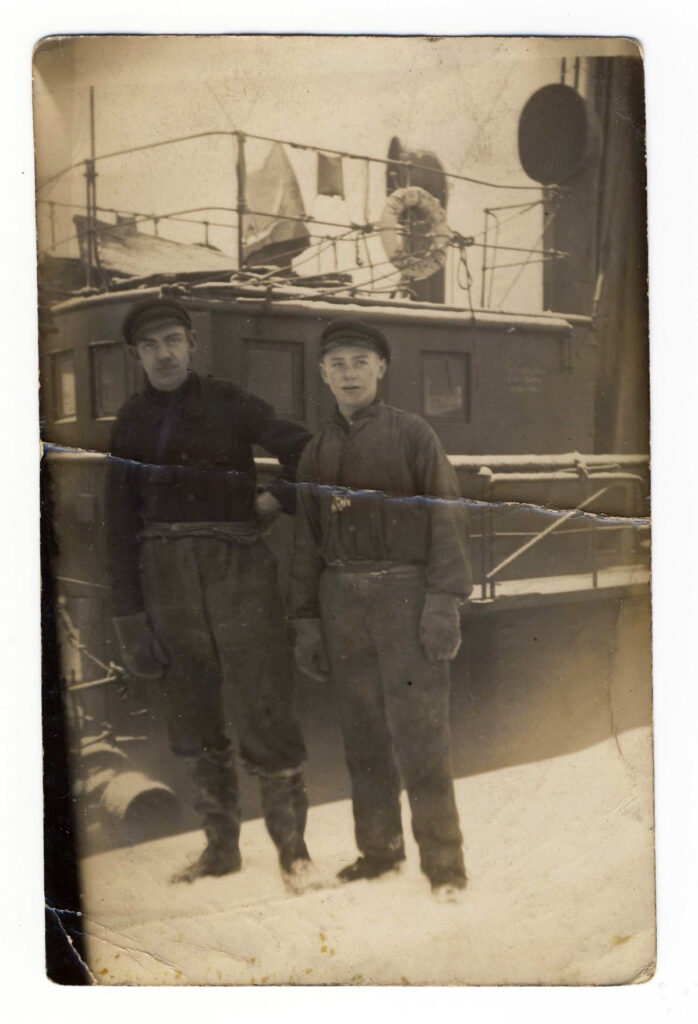

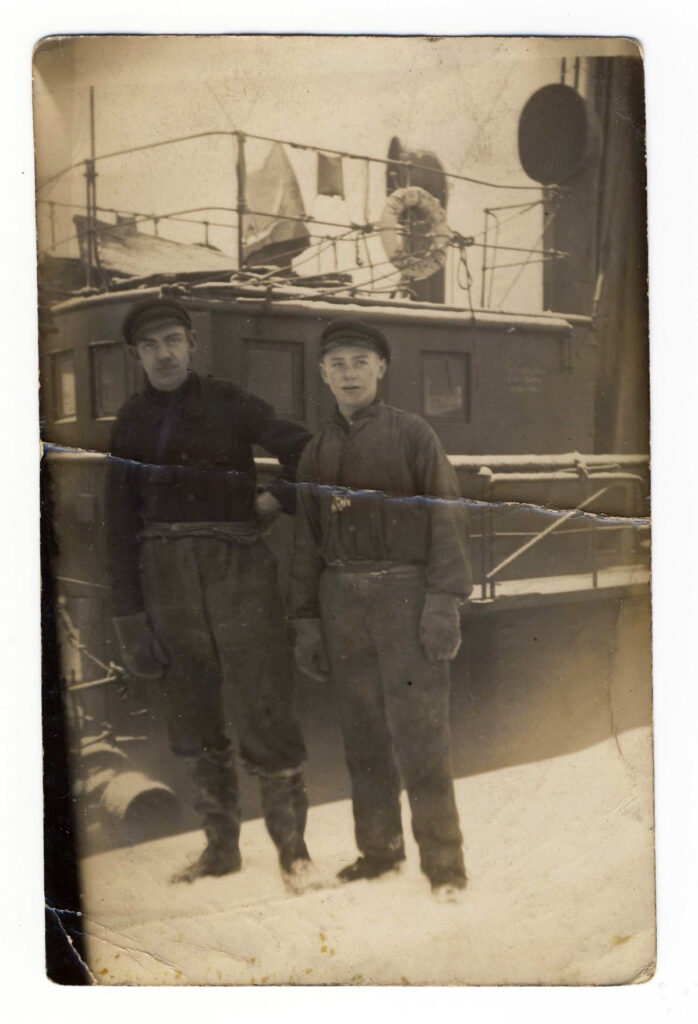

August Golla (rechts) im Hafen von Wesermünde (Bremerhaven), Postkarte vom 1.2.1928.

Privatbesitz Angelika Beltz.

Die Verlegung nach Pirna-Sonnenstein betraf nur männliche Erkrankte. Einer von ihnen war August Golla. Er stammte aus Wesermünde (heute Bremerhaven). August Golla arbeitete als Netzmacher und stand der Kommunistischen Partei nahe. Dies führte immer wieder zu Konflikten mit seinem Vater. Im November 1936 verhielt sich August Golla sonderbar und kam ins Krankenhaus. Von dort wurde er in die Lüneburger Heil- und Pflegeanstalt überwiesen.

Man bringt nur Männer nach Pirna-Sonnenstein.

Auch August Golla ist dabei.

Er kommt aus der Stadt Wesermünde.

Heute heißt die Stadt Bremerhaven.

Auf diesem Foto steht August Golla rechts.

August Golla arbeitet in der Fischerei.

Er macht zum Beispiel Fischer-Netze.

August Golla mag die Kommunistische Partei.

Sein Vater mag die Partei nicht.

Darum gibt es oft Streit.

Im November 1936 geht es August Golla

schlecht.

Darum kommt er in ein Krankenhaus.

Das Krankenhaus schickt ihn

in die Anstalt nach Lüneburg.

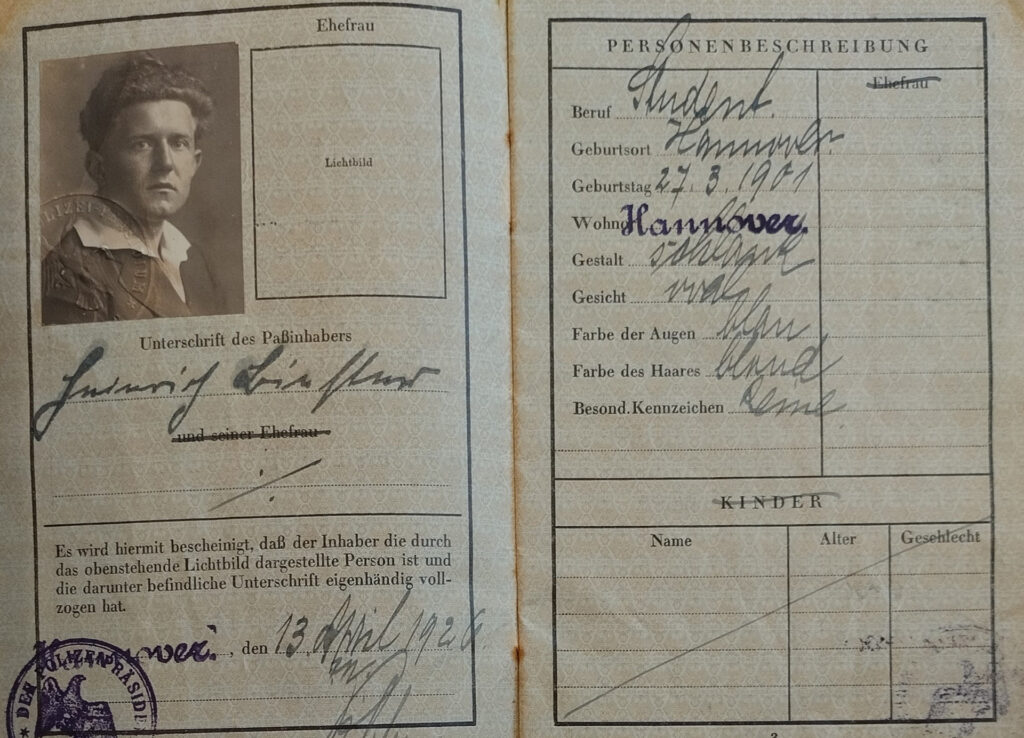

Carl Riemann war Polizeibeamter in Hamburg. Da er mit einer 15 Jahre jüngeren Jüdin verheiratet war, wurde er bei der Arbeit »gemobbt«. Das machte ihn krank. 1934 trennte sich das Paar. Er wurde in die Anstalt Friedrichsberg (Hamburg) aufgenommen, 1935 nach Hamburg-Langenhorn verlegt und 1936 von dort nach Lüneburg gebracht. Hier blieb er bis zu seiner Verlegung in die Tötungsanstalt Pirna-Sonnenstein. Als offizielles Todesdatum wurde der 24. März 1941 angegeben.

Das ist ein Führerschein

von Carl Riemann.

Carl Riemann lebt in Hamburg

und ist Polizist.

Er ist verheiratet.

Seine Frau ist 15 Jahre jünger als Carl und

sie ist Jüdin.

Darum mögen seine Kollegen Carl nicht.

Die Kollegen ärgern Carl.

Das macht ihn krank.

Carl und seine Frau trennen sich.

Carl kommt in eine Anstalt in Hamburg.

Von dort kommt er in die Anstalt

nach Lüneburg.

Im Jahr 1941 bringt man Carl Riemann

in die Tötungs-Anstalt Pirna-Sonnenstein.

Dort wird er ermordet.

In Carl Riemanns Kranken-Akte steht:

Carl stirbt am 24. März 1941.

Foto aus dem Führerschein von Carl Riemann, 1922.

Staatsarchiv Hamburg 352-8/7 Nr. 22076 | Kopie Martin Bähr.

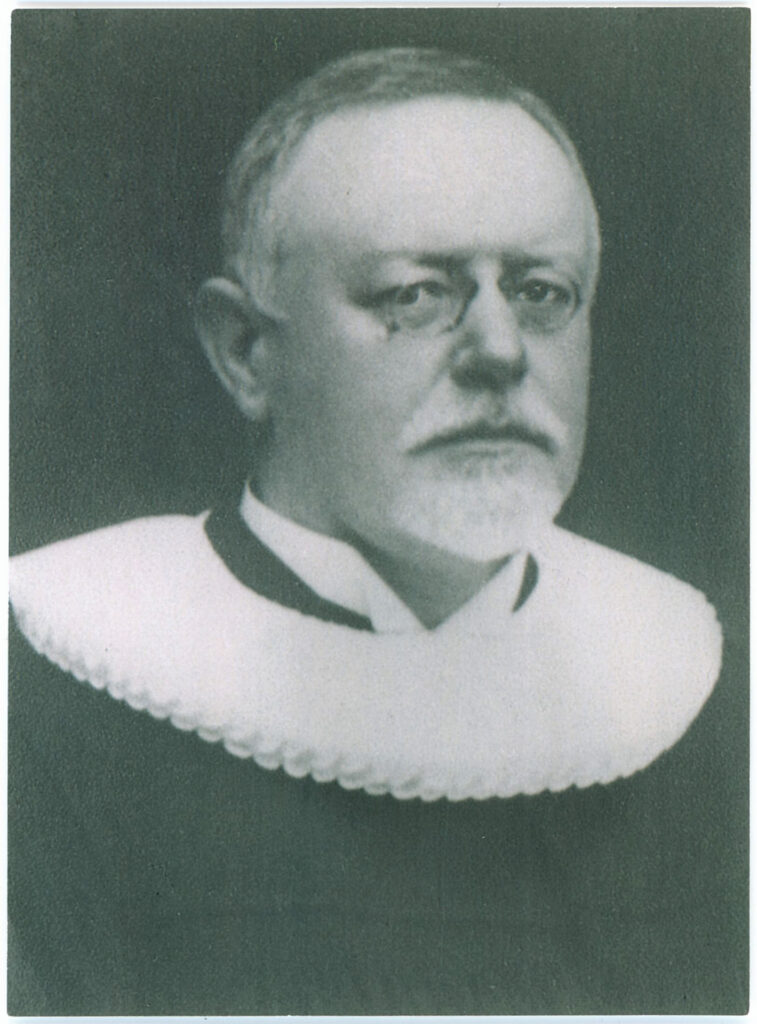

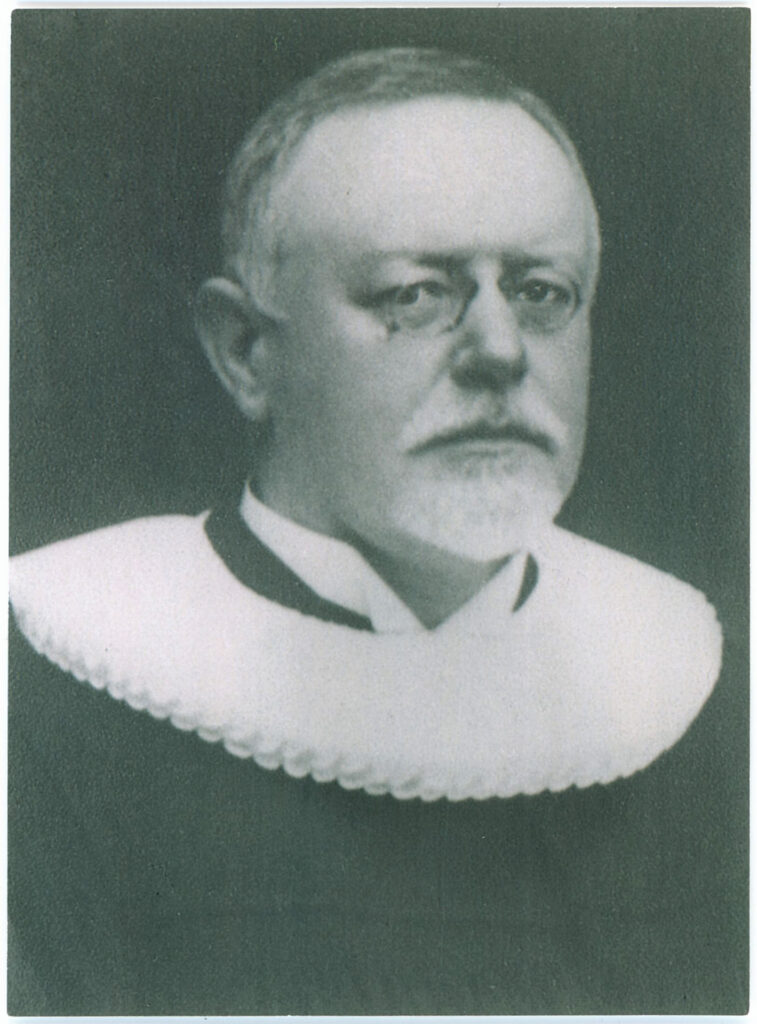

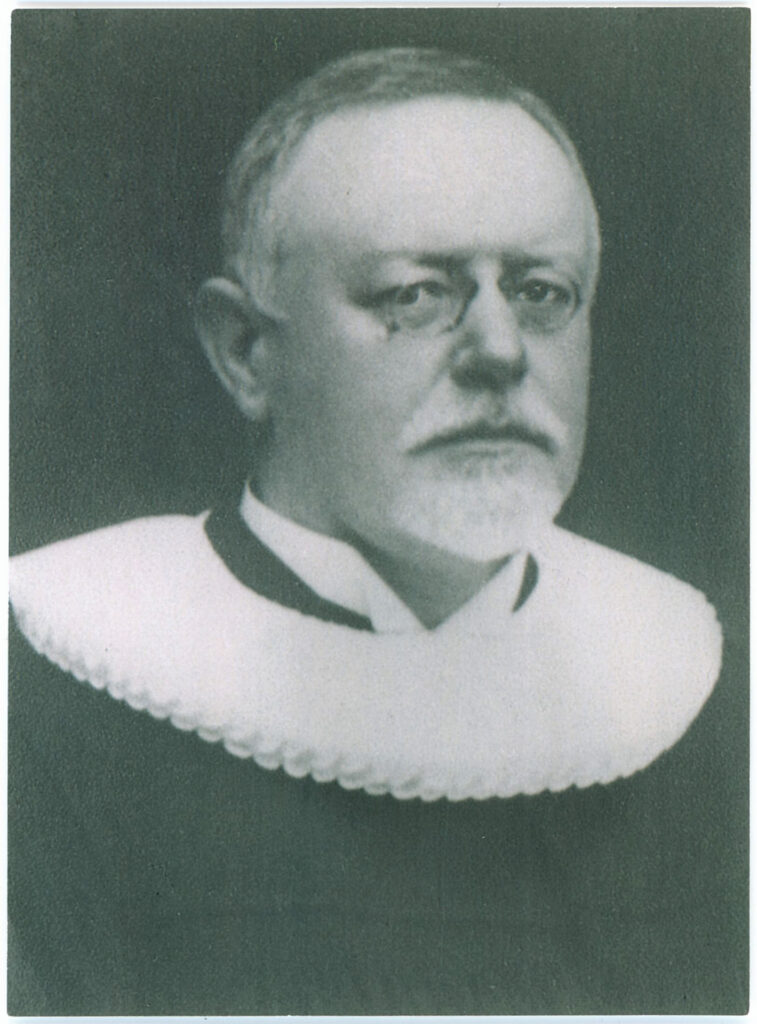

Johannes Müller, um 1916.

Privatbesitz Helga und Ludwig Müller.

Johannes Müller aus Geestemünde (Bremerhaven) war gelernter Kaufmann. Sein Vater war Sattler und stattete Luxusschiffe aus. Als junger Mann hatte Johannes Müller im Ersten Weltkrieg gedient und lebte danach ein unpolitisches, christlich geprägtes, bürgerliches Leben. Er erkrankte in den 1930er-Jahren. Nach seiner Ermordung in Pirna-Sonnenstein bestattete die Familie die Urne mit seiner Asche im Familiengrab, das noch heute existiert.

Das ist ein Foto von Johannes Müller

aus dem Jahr 1916.

Er lebt in Geestemünde.

Heute heißt die Stadt Bremerhaven.

Johannes Müller ist Kaufmann.

Er ist auch Soldat im Ersten Weltkrieg.

Nach dem Krieg lebt Johannes

ein normales Leben.

In der Nazi-Zeit wird Johannes krank.

Er kommt in die Anstalt in Lüneburg.

Von dort bringt man ihn

in die Tötungs-Anstalt Pirna-Sonnenstein.

Dort wird er ermordet.

Sein toter Körper wird verbrannt.

Dabei bleibt Asche übrig.

Die Asche kommt in eine Dose.

Die Dose nennt man: Urne.

Die Familie von Johannes bekommt

die Urne mit seiner Asche.

Die Familie legt die Urne in ein Grab.

Das Grab von Johannes gibt es heute noch.

Am 9., 23. und 30. April 1941 wurden insgesamt 357 Erkrankte der Heil- und Pflegeanstalt Lüneburg im Rahmen der »Aktion T4« in die Zwischenanstalt Herborn verlegt. Diese Verlegungen wurden von Beschäftigten der Heil- und Pflegeanstalt Lüneburg begleitet.

355 Erkrankte wurden am 12., 21. und 28. Mai sowie am 16. Juni 1941 von Herborn in die Tötungsanstalt Hadamar verlegt. Dort stiegen die Erkrankten in einer Garage aus den Bussen aus. Sie wurden noch einmal medizinisch untersucht, in die im Keller gelegene Gaskammer geführt und ermordet. Nur zwei Lüneburger Erkrankte überlebten, weil sie bei der Untersuchung in der Garage als ausreichend arbeitsfähig bewertet wurden.

3-mal bringt man Kranke aus Lüneburg

in die Zwischenanstalt Herborn:

• am 9. April 1941.

• am 23. April 1941.

• am 30. April 1941.

357 Kranke aus Lüneburg kommen nach Herborn.

Ihre Pfleger sind mit dabei.

In Herborn warten die Kranken mehrere Wochen.

Dann bringt man sie

in die Tötungs-Anstalt Hadamar:

• am 12. Mai 1941.

• am 21. Mai 1941.

• am 28. Mai 1941.

• am 16. Juni 1941.

Die Kranken fahren mit Bussen

in die Tötungs-Anstalt nach Hadamar.

Die Kranken steigen aus den Bussen aus.

Die Nazis untersuchen die Kranken.

Dann bringt man sie in einen Keller.

Dort ist die Gas-Kammer.

In die Gas-Kammer fließt Gas.

Die Kranken atmen das Gas ein und ersticken.

Sie sterben in der Gas-Kammer.

2 Kranke aus Lüneburg überleben in Hadamar.

Sie werden nicht ermordet.

Die Nazis bewertet sie beim Aussteigen

aus dem Bus.

Man glaubt, sie können gut arbeiten.

Darum ermordet man sie nicht.

Tötungsanstalt Hadamar mit rauchendem Schornstein, 1941.

Archiv des Landeswohlfahrtsverbandes Hessen, F 12/Nr. 192.

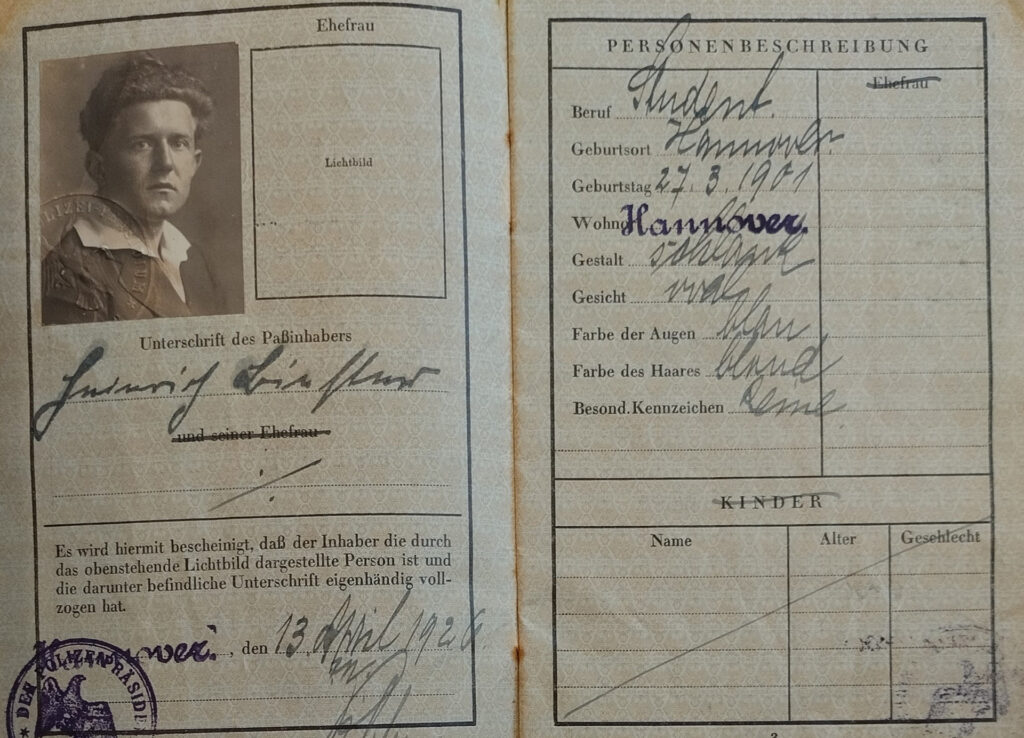

Reisepass von Heinrich Biester, ausgestellt am 13.4.1926.

ArEGL 127.

Ein Studium in den USA war geplant, dafür brauchte Heinrich Biester einen Reisepass. Doch dann erkrankte er und kehrte 1926 nach Hause zurück. Sein Zustand besserte sich nicht, und so kam er 1927 in die Heil- und Pflegeanstalt Lüneburg.

Das ist ein Reisepass von Heinrich Biester

aus dem Jahr 1926.

Heinrich Biester will Musiker werden.

Er studiert in Hannover und Wien.

Und er plant ein Studium in den USA.

Aber dann wird Heinrich Biester krank.

Im Jahr 1926 kommt er aus den USA

zurück nach Hause.

Es geht ihm schlecht.

Darum kommt er im Jahr 1927 in die Anstalt nach Lüneburg.

In der Anstalt arbeitet Heinrichs Onkel.

Der Onkel heißt: Heinrich Mund.

Heinrich Mund ist Pastor in der Anstalt.

Heinrich Mund soll auf seinen Neffen

Heinrich Biester aufpassen.

Heinrich Biester macht bei Gottesdiensten mit.

Er spielt Geige in den Gottesdiensten.

Das soll eine Art Therapie für ihn sein,

weil er ja Musiker werden will.

Aber davon wird er auch nicht wieder gesund.

Er bleibt krank.

Die Nazis bringen Heinrich Biester

in die Tötungs-Anstalt Hadamar.

Dort ermorden sie ihn am 21. Mai 1941.

Der Onkel Heinrich Mund schreibt Tagebuch.

Im Tagebuch stehen viele Infos

über die Anstalt in Lüneburg.

Zum Beispiel:

Wie war das Leben in der Anstalt?

Es gibt auch Infos über den Kranken-Mord.

Aber die Infos sind sehr versteckt.

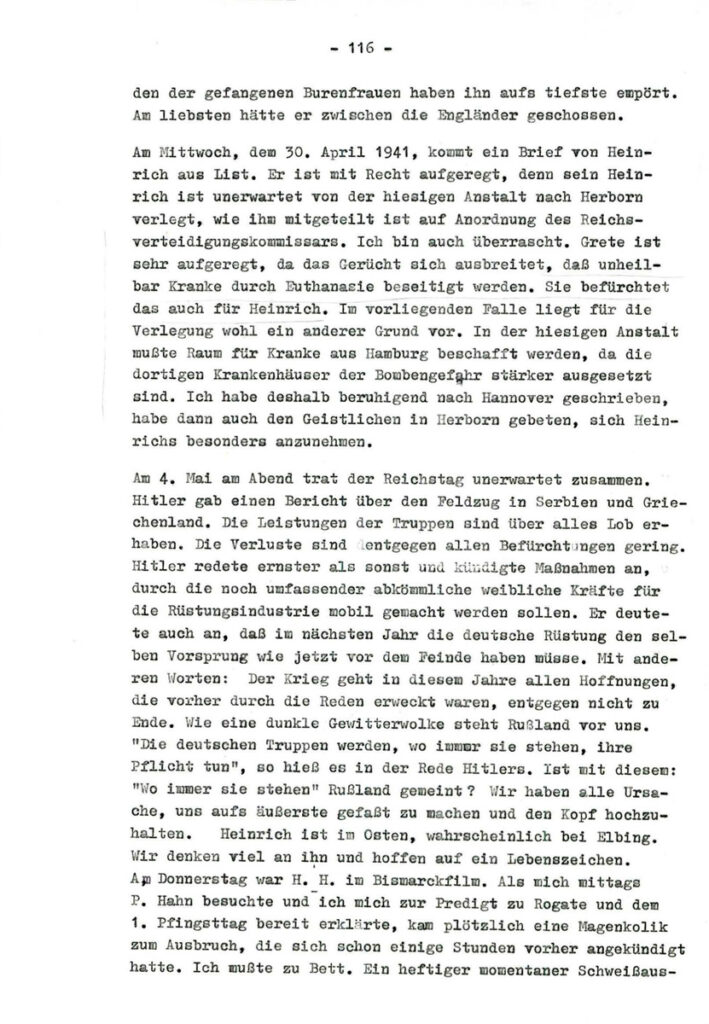

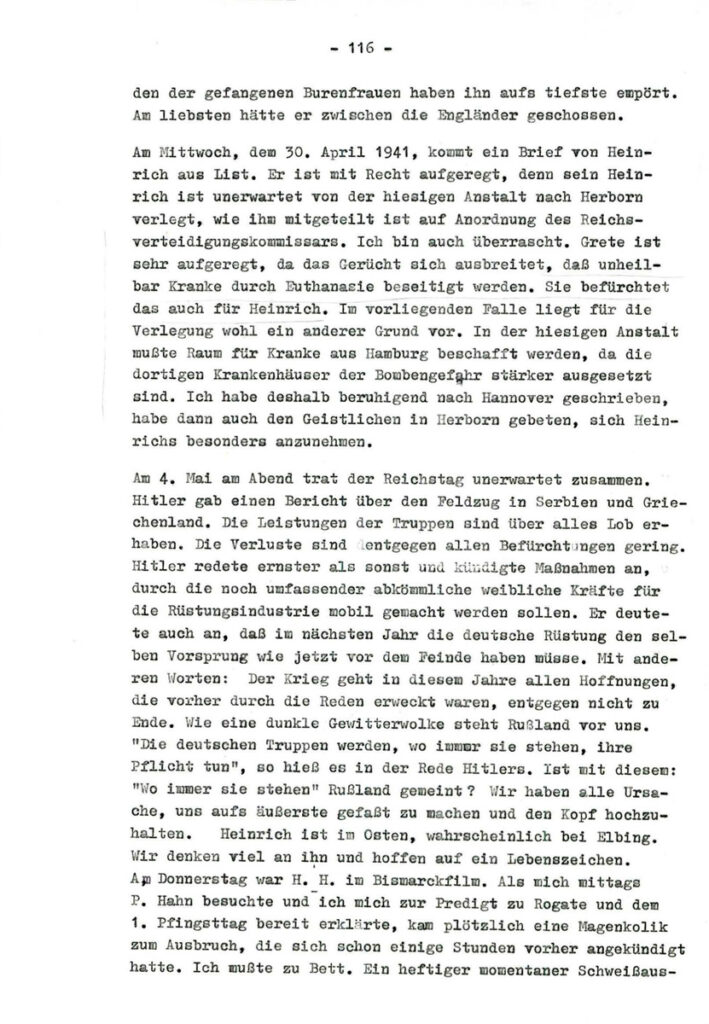

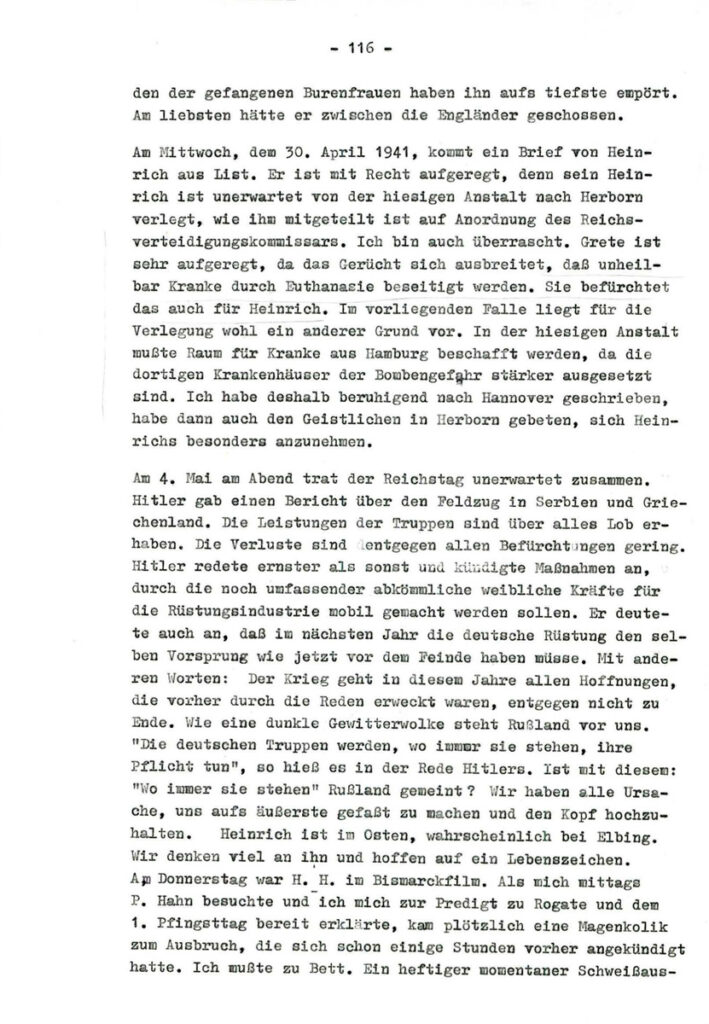

Das Tagebuch von Heinrich Mund beginnt am 1. Januar 1926 und endet am 1. September 1944. Er beschreibt die Situation in der Heil- und Pflegeanstalt Lüneburg zur damaligen Zeit. Versteckt kommen Hinweise auf den Krankenmord vor. Er deutet an, dass zu viele Kinder in der Heil- und Pflegeanstalt sterben, die er als Seelsorger bestatten muss. Auch die Sorge über die Verlegung seines Neffen Heinrich Biester und die Empörung über dessen plötzlichen Tod finden sich im Tagebuch wieder.

Das ist ein Teil aus dem Tagebuch

von Heinrich Mund.

Heinrich Mund schreibt:

Er macht sich Sorgen um Heinrich Biester.

Er denkt:

Die Nazis wollen Heinrich Biester ermorden.

Es sterben auch sehr viele Kinder

in der Anstalt in Lüneburg.

Das merkt Heinrich Mund.

Er zählt die Kinder.

Aber er traut sich nicht die Wahrheit

zu schreiben:

Die Kinder werden ermordet.

Heinrich Mund 1871 – 1945. Tagebuchnotizen aus den Jahren 1926, 1935 und 1937 – 1945, Abschrift und Auszug, S. 116.

ArEGL 161.

Heinrich Mund, vor 1945.

Privatsammlung Familie Mund.

HEINRICH BIESTER (1901 – 1941)

Gruppenfoto der Familie Biester. Heinrich Biester steht in der letzten Reihe, Zweiter von rechts. Links neben ihm steht sein Vater, Hannover, 1925.

Privatbesitz Familie Biester.

Heinrich Biester wuchs in Hannover-List auf. Er wollte Musiker werden und studierte ab 1924 Musik und Gesang in Hannover und Wien. Ein Studium in den USA war geplant. Doch dann erkrankte er und kehrte 1926 nach Hause zurück. Sein Zustand besserte sich nicht, und so kam er 1927 in die Heil- und Pflegeanstalt Lüneburg. Dort war sein Onkel Heinrich Mund seit 1907 Anstaltspfarrer. Er sollte auf seinen Neffen aufpassen. Heinrich Biester nahm an den Gottesdiensten in der Anstalt teil und spielte dort Geige. Doch dies schützte ihn nicht. Er wurde am 21. Mai 1941 in der Tötungsanstalt Hadamar ermordet. Seine Angehörigen hatten sofort den Verdacht, dass ein Verbrechen geschehen war. Die christlich geprägte Familie verzichtete darauf, die Urne mit seiner vermeintlichen Asche überführen und zu Hause bestatten zu lassen.

HEINRICH BIESTER

Heinrich Biester kommt aus Hannover.

Er macht Musik:

Er spielt Geige und er singt.

Er will Musiker werden.

Aber dann wird er krank.

Sein Onkel ist Pastor

in der Anstalt in Lüneburg.

Darum kommt Heinrich in die Anstalt

nach Lüneburg.

Heinrich Biester spielt auch

in der Anstalt Geige.

Zum Beispiel: beim Gottesdienst.

Sein Onkel soll auf ihn aufpassen.

Aber Heinrich Biester kommt trotzdem

in die Tötungs-Anstalt Hadamar.

Dort wird er am 21. Mai 1941 ermordet.

Sein Onkel und die Familie vermuten:

Die Nazis haben Heinrich ermordet.

Die Familie holt die Asche von Heinrich Biester nicht nach Hause.

Das ist ein Foto von Heinrich Biester

aus dem Jahr 1925.

Er steht in der hinteren Reihe.

Er ist der zweite von rechs.

Links neben Heinrich steht sein Vater.

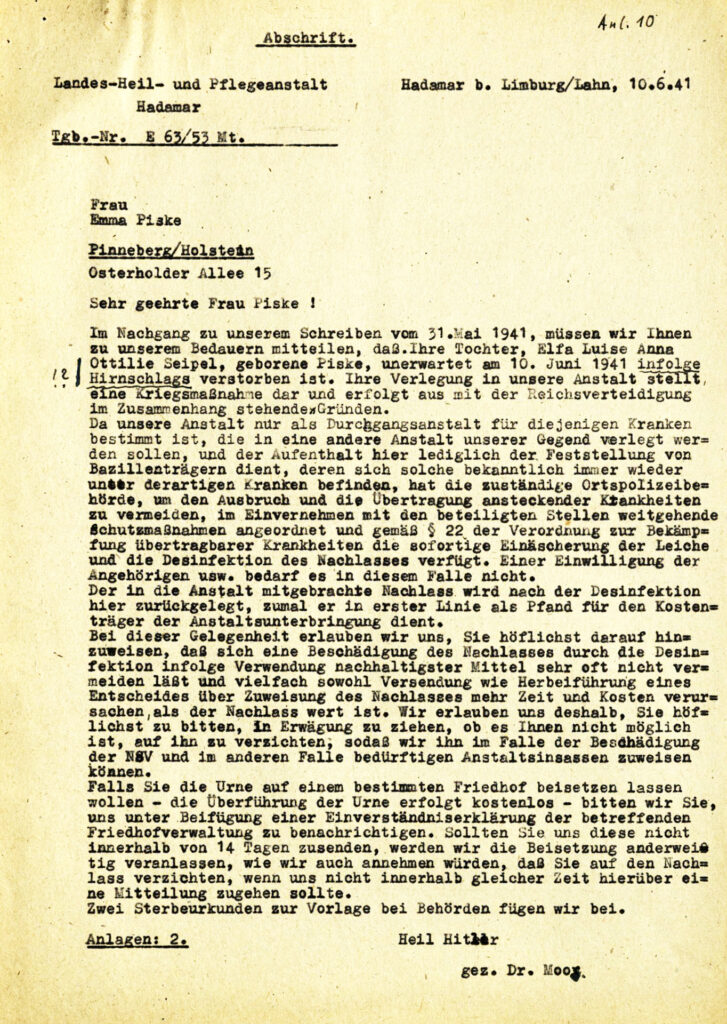

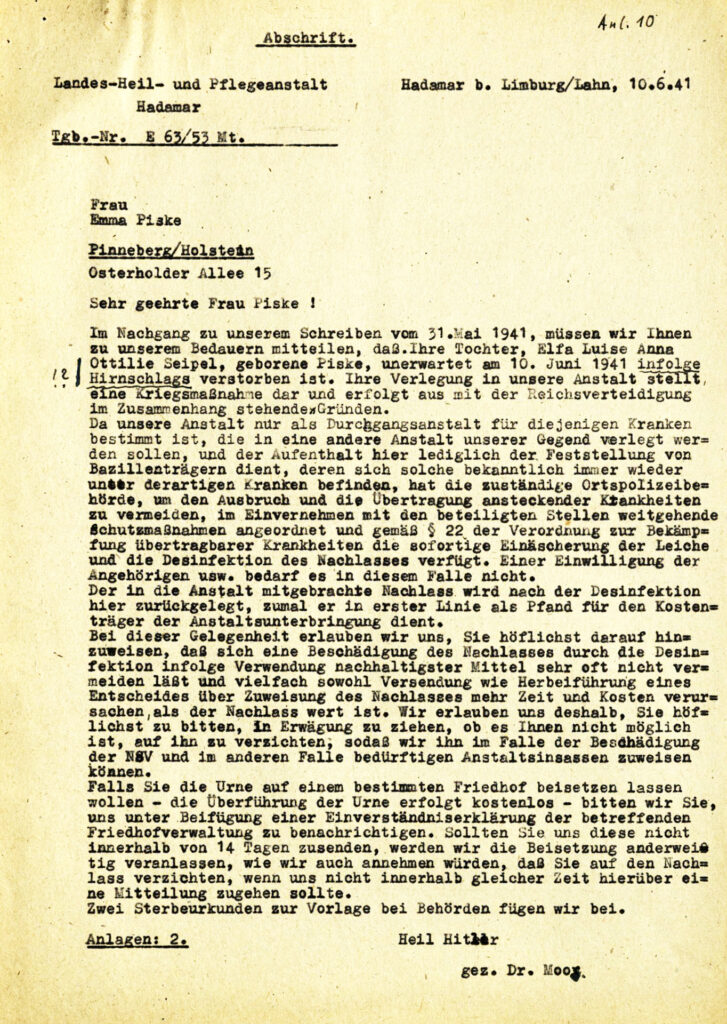

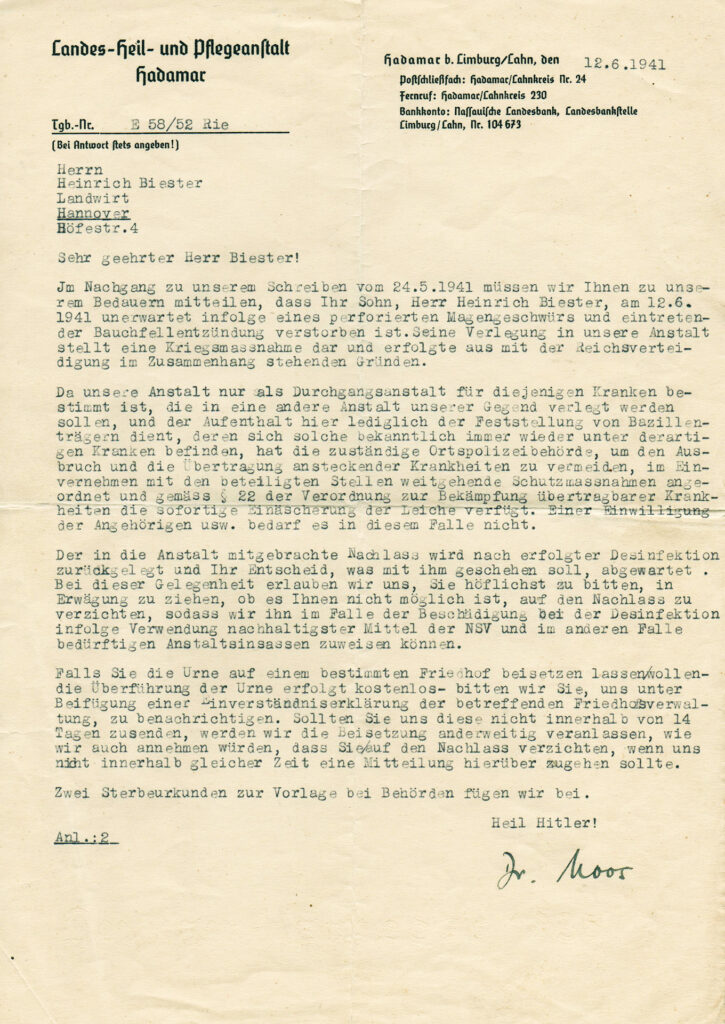

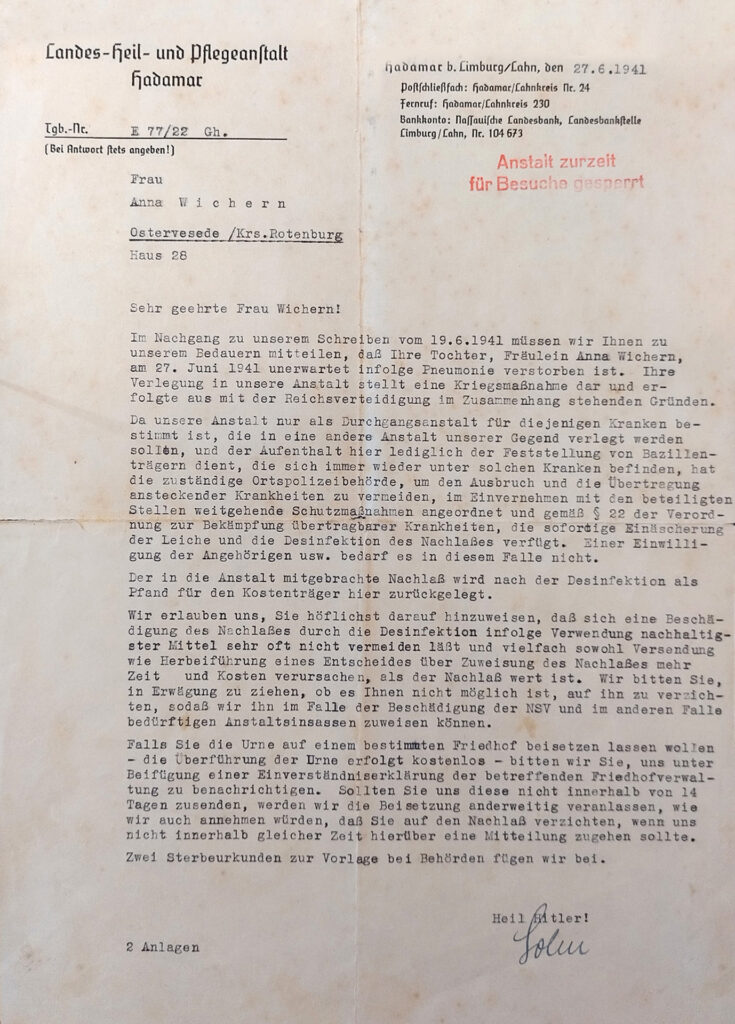

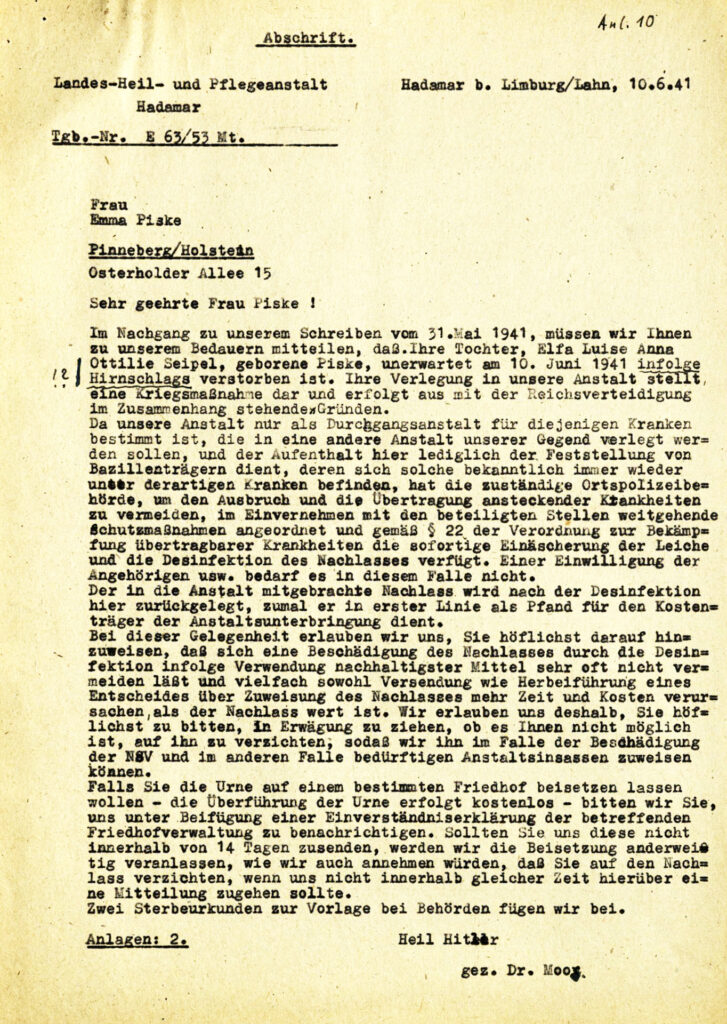

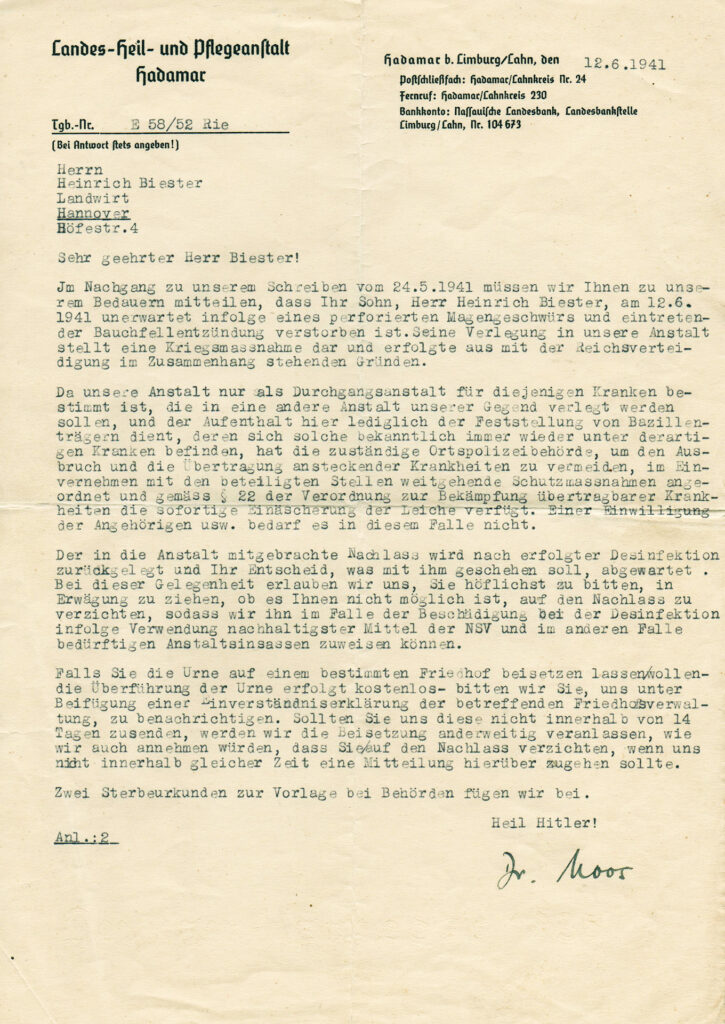

»Trostbrief« der Heil- und Pflegeanstalt Hadamar über den Tod von Elfa Seipel an Emma Piske vom 10.6.1941.

Privatbesitz Ulla Bucarey.

Die Angehörigen wurden 10 bis 20 Tage nach dem Mord mit einem immer gleich lautenden »Trostbrief« über den »unerwarteten« Tod informiert. Die Ursache war dabei genauso frei erfunden wie der Todestag. Durch das Verschieben des Todes auf ein späteres Datum konnten noch Pflegegelder für die Getöteten abgerechnet werden. Davon wurden die Morde bezahlt.

Die Nazis ermorden viele Kranke bei der Aktion T4.

Danach bekommen die Familien

von den Toten einen Brief.

Der Brief heißt: Trost-Brief.

In den Trost-Briefen steht immer das Gleiche:

Das Familien-Mitglied ist tot.

Der Kranke ist gestorben, weil er krank war.

Aber das ist eine Lüge.

Denn die Nazis haben die Kranken ermordet.

Auch das Todes-Datum stimmt nicht.

Die Kranken sind früher gestorben,

als in dem Brief steht.

Das ist der Grund dafür:

Die Anstalt bekommt Geld für die Kranken.

Ist ein Kranker lange in der Anstalt,

bekommt die Anstalt mehr Geld.

Darum lügt man beim Todes-Datum.

Man tut so, als ob der Kranke später gestorben ist.

So bekommt die Anstalt mehr Geld.

Die Nazis bezahlen mit dem Geld

den Kranken-Mord.

Zum Beispiel: die Fahr-Karten, das Gas.

Heute gibt es noch 3 Trost-Briefe

von Kranken aus der Anstalt in Lüneburg

Die Trost-Briefe sind für die Familien von:

• Elfa Seipel.

• Heinrich Biester.

• Anna Wichern.

Sie sind alle in der Tötungs-Anstalt

in Hadamar ermordet worden.

Elfa (links) Seipel (geb. Piske) mit ihrer Schwester Paula, vor 1914.

Privatbesitz Ulla Bucarey.

Das ist ein Foto von Elfa Seipel

und ihrer Schwester Paula.

Es ist aus dem Jahr 1914.

Das ist ein Foto von Heinrich Biester.

Es ist aus dem Jahr 1927.

Heinrich Biester, um 1927.

NLA Hannover Hann. 155 Lüneburg Acc. 2004/066 Nr. 07588.

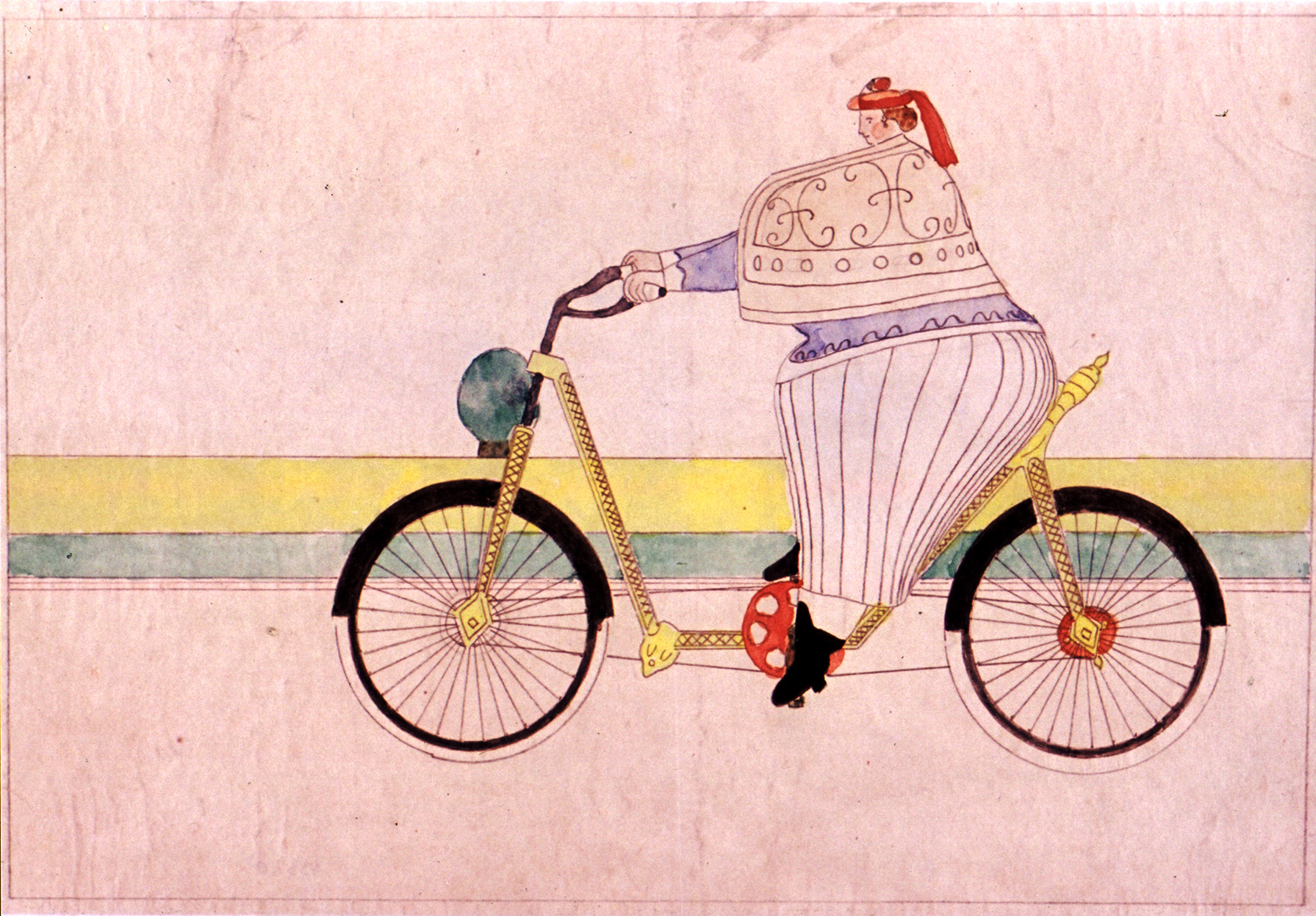

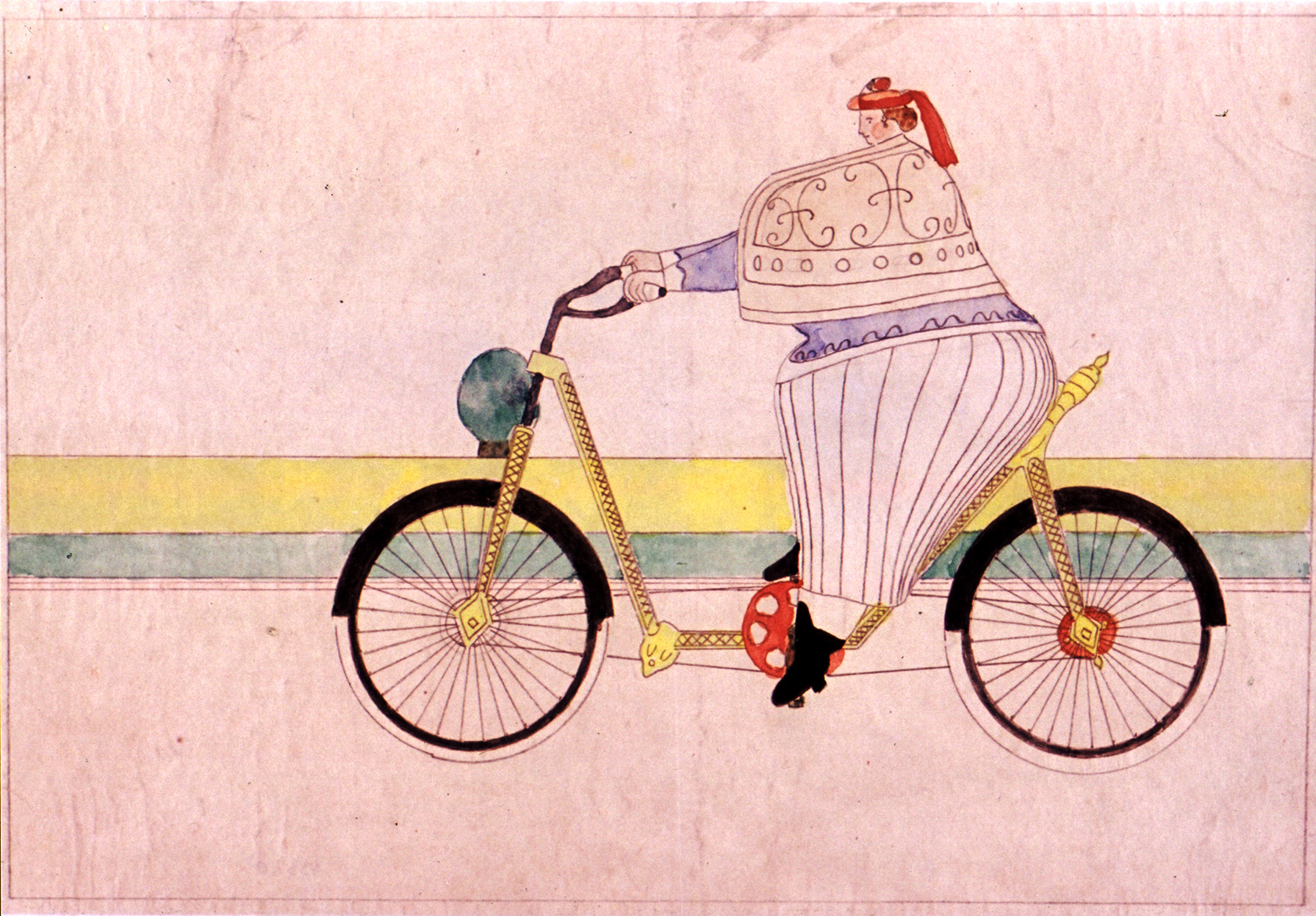

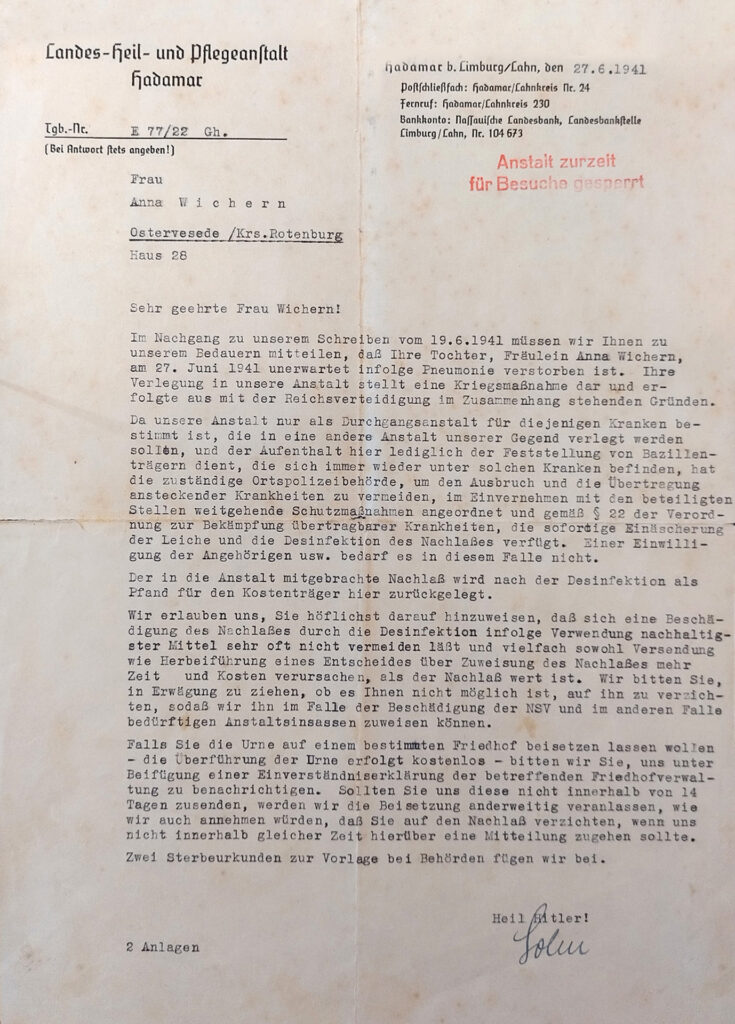

Werk von Gustav Sievers. Ohne Titel, undatiert, Bleistift, Wasserfarben auf Durchschlagpapier.

Sammlung Prinzhorn Inv. Nr. 4332d.

Carl Langhein, vor 1905.

Aus: Adolf von Oechelhäuser: Geschichte der Grossh. Badischen Akademie der bildenden Künste, Karlsruhe 1904.

Werbe-Postkarte von Carl Langhein, Wertvolles Strandgut Kupferberg Gold, Lithografie, vor 1927.

ArEGL 187.

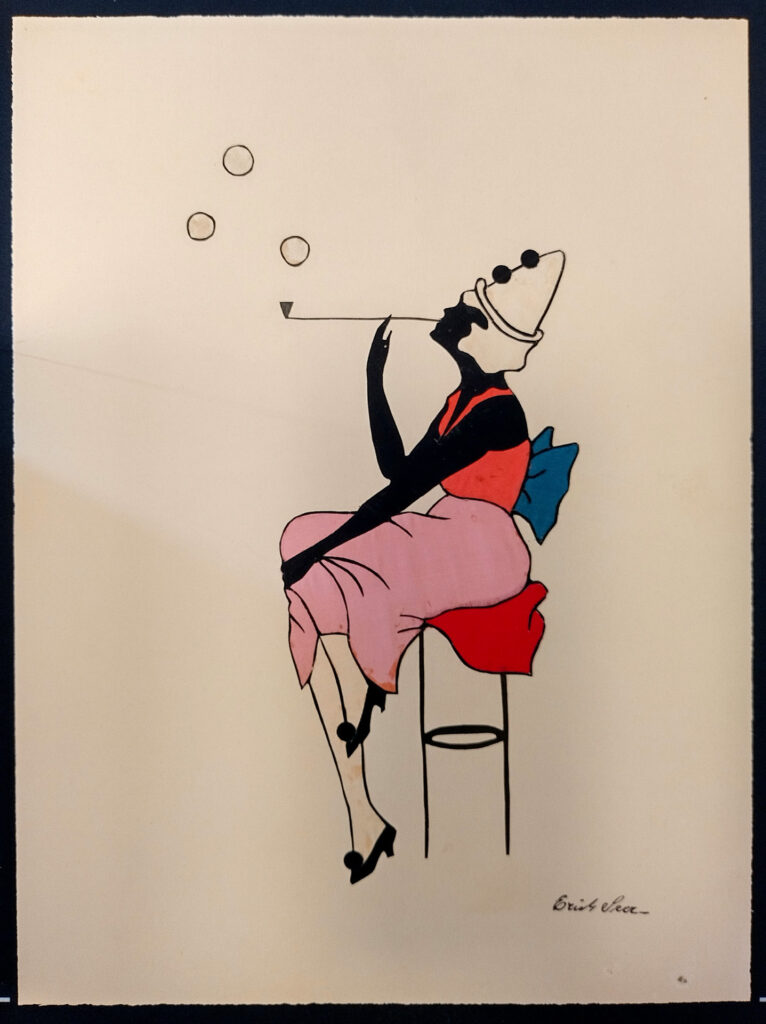

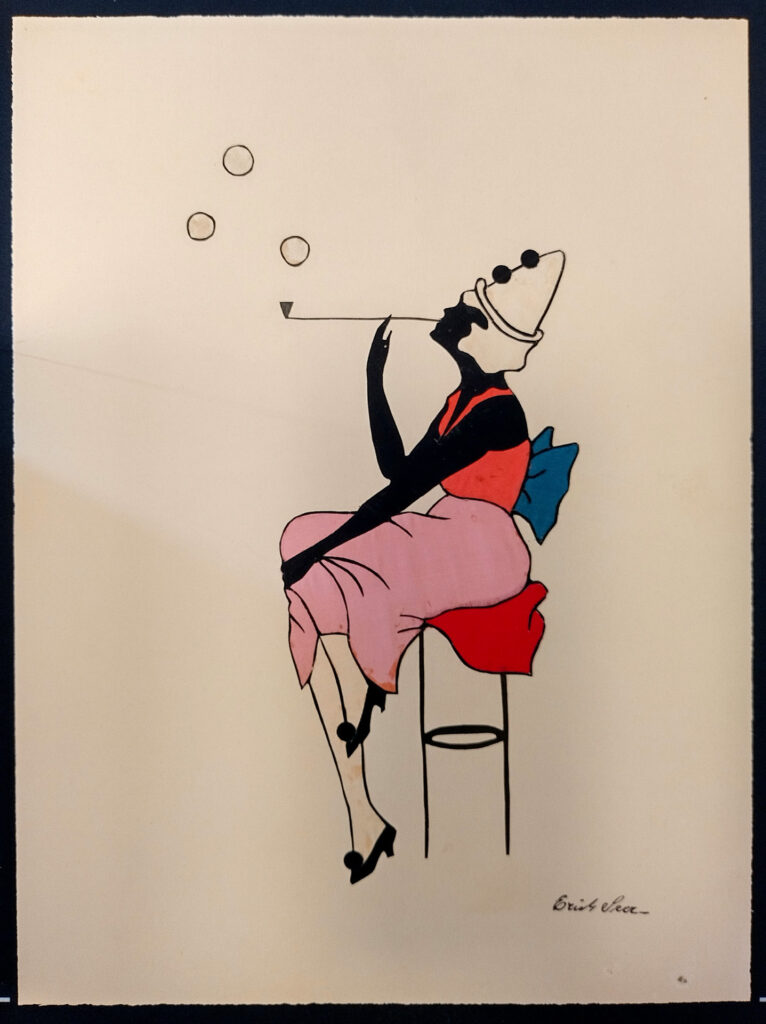

Unter den Opfern der »Aktion T4« befanden sich viele Kunstschaffende und Kreative, deren Werke entwertet wurden. Einer von ihnen war Gustav Sievers, dessen Werke heute in der Sammlung Prinzhorn bewahrt werden. Erich Seer war erfolgreicher Grafiker, bevor er erkrankte. Zu Lebzeiten als Künstler und Lithograph geehrt wurde auch Carl Langhein. 1906 wurde ihm der Professorentitel verliehen, 1918 gründete er den Hanseatischen Kunstverlag.

Die Nazis ermorden bei der Aktion T4

viele Künstler.

Diese Künstler haben eine seelische Krankheit.

Die Nazis sagen:

Darum sind die Kunstwerke

von den Künstlern nichts wert.

Einer dieser Künstler ist Gustav Sievers.

Seine Kunstwerke sind heute

in der Sammlung Prinzhorn.

Erich Seer war auch Künstler.

Seine Kunst ist aus Schrift und Malerei.

Er ist sehr erfolgreich.

Aber dann wird er krank.

Er kann nicht mehr arbeiten.

Carl Langhein ist auch Künstler.

Er macht Kunst aus Schrift.

Er ist auch Lehrer für Kunst.

Er bildet andere Künstler aus.

Im Jahr 1906 ist er Professor.

Carl Langhein gründet einen Verlag

für Kunst-Bücher.

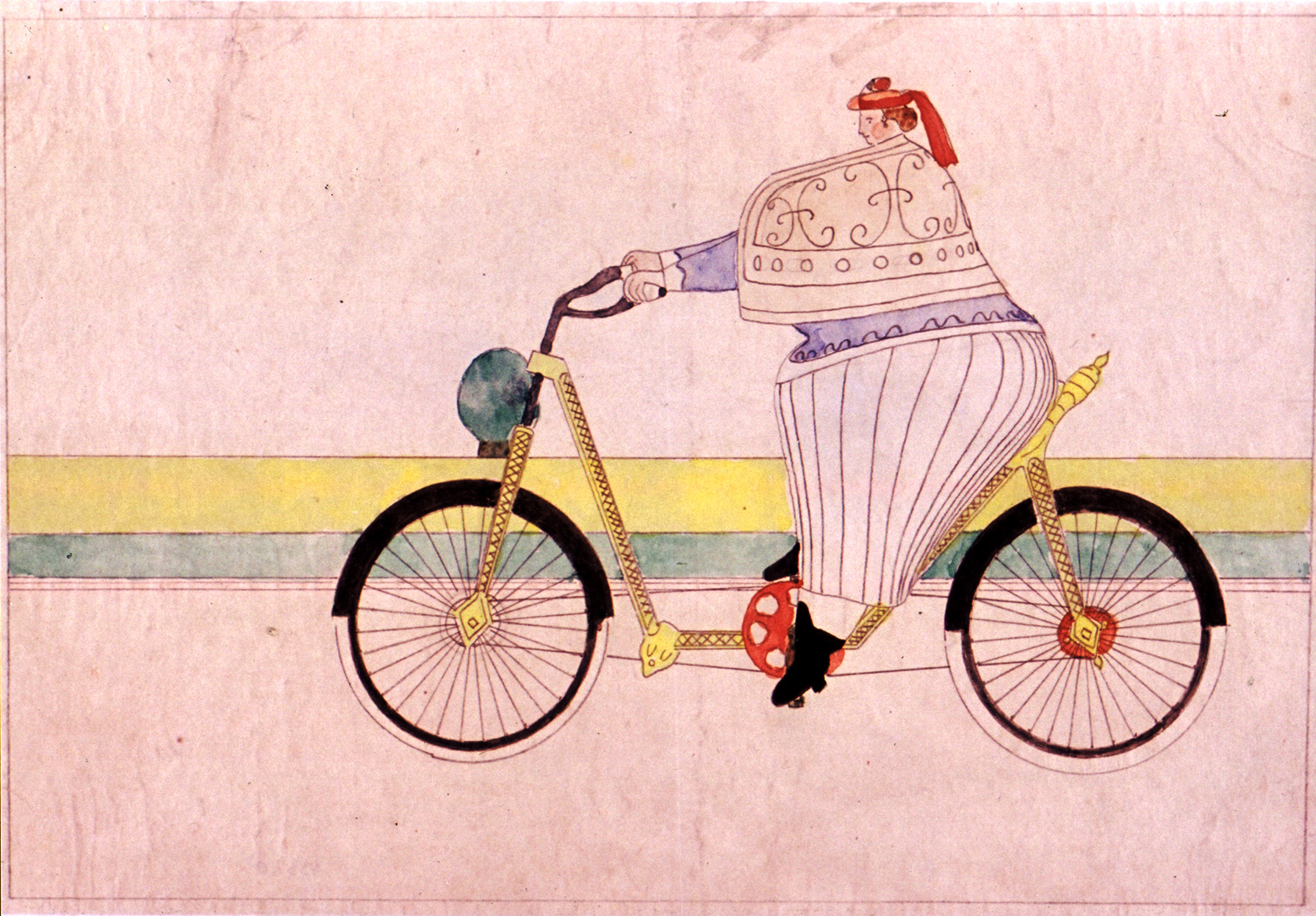

Die Collage zeigt eine Frau, die als Harlekin verkleidet auf einem Barhocker sitzt und mithilfe einer Pfeife Seifenblasen pustet. Es gibt drei weitere Bilder gleicher Machart. Der Grafiker und Künstler Erich Seer (1894 – 1941) hat sie aus verschiedenfarbiger Seide und schwarzem Karton geklebt. Ab 1938 war er Patient in Lüneburg und wurde am 7. März 1941 in der Tötungsanstalt Pirna-Sonnenstein ermordet.

Das ist ein Kunstwerk von Erich Seer.

Es ist ein Scheren-Schnitt aus Papier und Stoff.

Erich Seer kommt im Jahr 1938

in die Anstalt nach Lüneburg.

Am 7. März 1941 bringt man ihn

in die Tötungs-Anstalt Pirna-Sonnenstein.

Dort ermordet man ihn.

Collage von Erich Seer, vor 1941.

ArEGL 184.

Im Vergleich zu Männern wurden Frauen häufiger Opfer der Krankenmorde. Ihre Erkrankungen wurden oft durch Schwangerschaft oder Geburt ausgelöst, manchmal waren sie Opfer ehelicher Gewalt. Da sie meist keinen Beruf erlernt hatten, galten sie als »unnütz« und »lebensunwert«.

Die Nazis ermorden viele Menschen

bei der Aktion T4 und beim Kranken-Mord.

Es werden mehr Frauen als Männer ermordet.

Denn viele Frauen haben keinen Beruf.

Sie sind Hausfrauen.

Die Nazis denken:

Kranke Hausfrauen sind zu nichts

zu gebrauchen.

Sie haben kein Recht zu leben.

Darum werden sie oft ausgewählt

für den Kranken-Mord.

Elsa und Heinrich Spartz (mittig), um 1911.

Privatbesitz Maria Kiemen/Matthias Spartz.

Christine Sauerbrey, vor 1914.

Privatbesitz Traute Konietzko.

Agnes Fiebig (spätere Timme), 1929.

Privatbesitz Sabine Röhrs.

Die Hälfte der weiblichen Opfer der »Aktion T4« war verheiratet. Der Ehemann von Elsa Spartz war Chefarzt des Hamburger St. Marien-Krankenhauses. Obwohl er vom Krankenmord wusste, rettete er seine Frau nicht. Christine Sauerbrey blieb ihrem Ehemann treu, als er politisch verfolgt wurde. Als sie erkrankte, ließ er sich von ihr scheiden. Als Agnes Timme nach der Geburt ihres vierten Kindes erkrankte, kümmerte sich ihr Ehemann nicht mehr um die gemeinsamen Kinder. Sie kamen in ein Heim.

Viele Frauen sind verheiratet,

wenn sie bei der Aktion T4 ermordet werden.

Auch Elsa Spartz wird ermordet.

Ihr Mann ist Arzt.

Er weiß von den Morden.

Aber er rettet seine Frau nicht.

Sie wird ermordet.

Christine Sauerbrey ist verheiratet.

Ihr Mann ist Kommunist.

Das sind Gegner von den Nazis.

Er kommt ins Gefängnis und er flüchtet.

Christine bleibt ihrem Mann treu.

Dann wird sie krank.

Ihr Mann verlässt sie und lässt sich scheiden.

Sie wird ermordet.

Agnes Timme bekommt 4 Kinder.

Dann wird sie krank.

Ihr Mann kümmert sich nicht um sie

und die Kinder.

Die Kinder von Agnes Timme kommen in ein Heim.

Sie wird ermordet.

Auch ein wohlständiger, bürgerlicher Hintergrund und eine private Kostenübernahme des Anstaltsaufenthaltes schützten nicht vor der Verlegung in eine Tötungsanstalt. Erkrankte mit bürgerlicher Herkunft waren hin und wieder unwillig, in der Heil- und Pflegeanstalt stundenlang körperlich harte Arbeit auf dem Feld, in der Schäl- oder Waschküche zu leisten. Erkrankte, die sich verweigerten, kamen daher eher für die Verlegung in eine Tötungsanstalt infrage.

Es gibt auch Kranke mit viel Geld.

Und es gibt Kranke, die wichtige Personen kennen.

Zum Beispiel: Politiker.

Aber das hilft ihnen nicht.

Sie kommen auch in Tötungs-Anstalten.

Die Kranken müssen in der Anstalt

in Lüneburg hart arbeiten.

Einige Kranke wollen nicht arbeiten.

Vor allem Kranke mit viel Geld wollen

nicht arbeiten.

Sie wollen auch nicht helfen.

Zum Beispiel:

• in der Küche.

• in der Wäscherei.

• bei der Garten-Arbeit.

Die Ärzte bewerten sie dann als faul.

Die Nazis wollen keine faulen Kranken.

Wer nicht hart arbeitet,

kommt in eine Tötungs-Anstalt.

Irmgard Ruschenbusch, um 1917.

Privatbesitz Michael Schade.

Irmgard Ruschenbusch war Arzttochter und kam aus einer freichristlichen Familie, aus der viele Pastoren und Missionare hervorgegangen waren. Ihre Herkunft bewahrte sie nicht vor der Ermordung.

Das ist ein Foto von Irmgard Ruschenbusch.

Ihre Familie hat viel Geld.

Ihr Vater ist Arzt.

Ihre Familie ist sehr christlich.

Sie glauben an Gott und gehen in die Kirche.

Irmgard Ruschenbusch wird trotzdem ermordet.

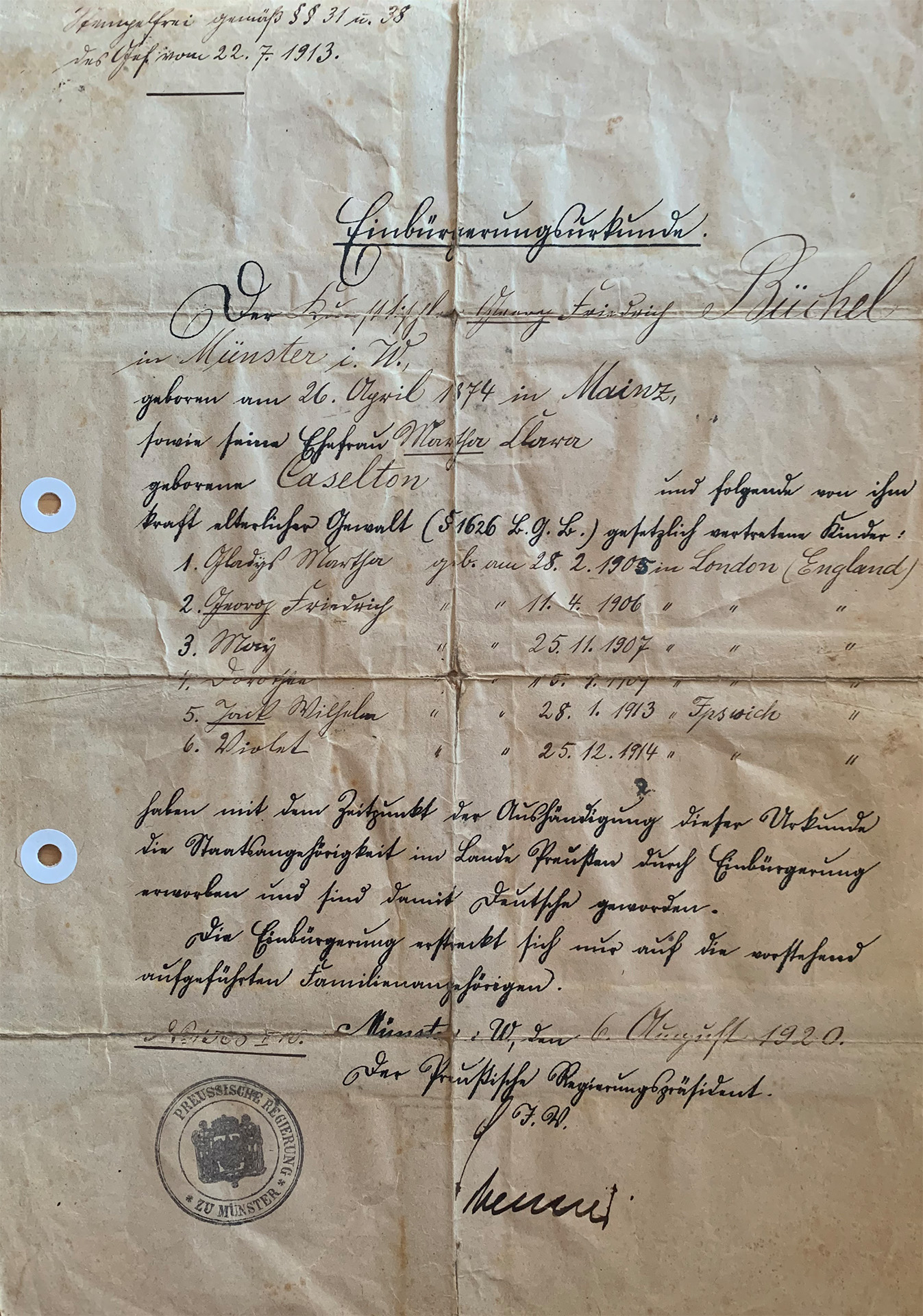

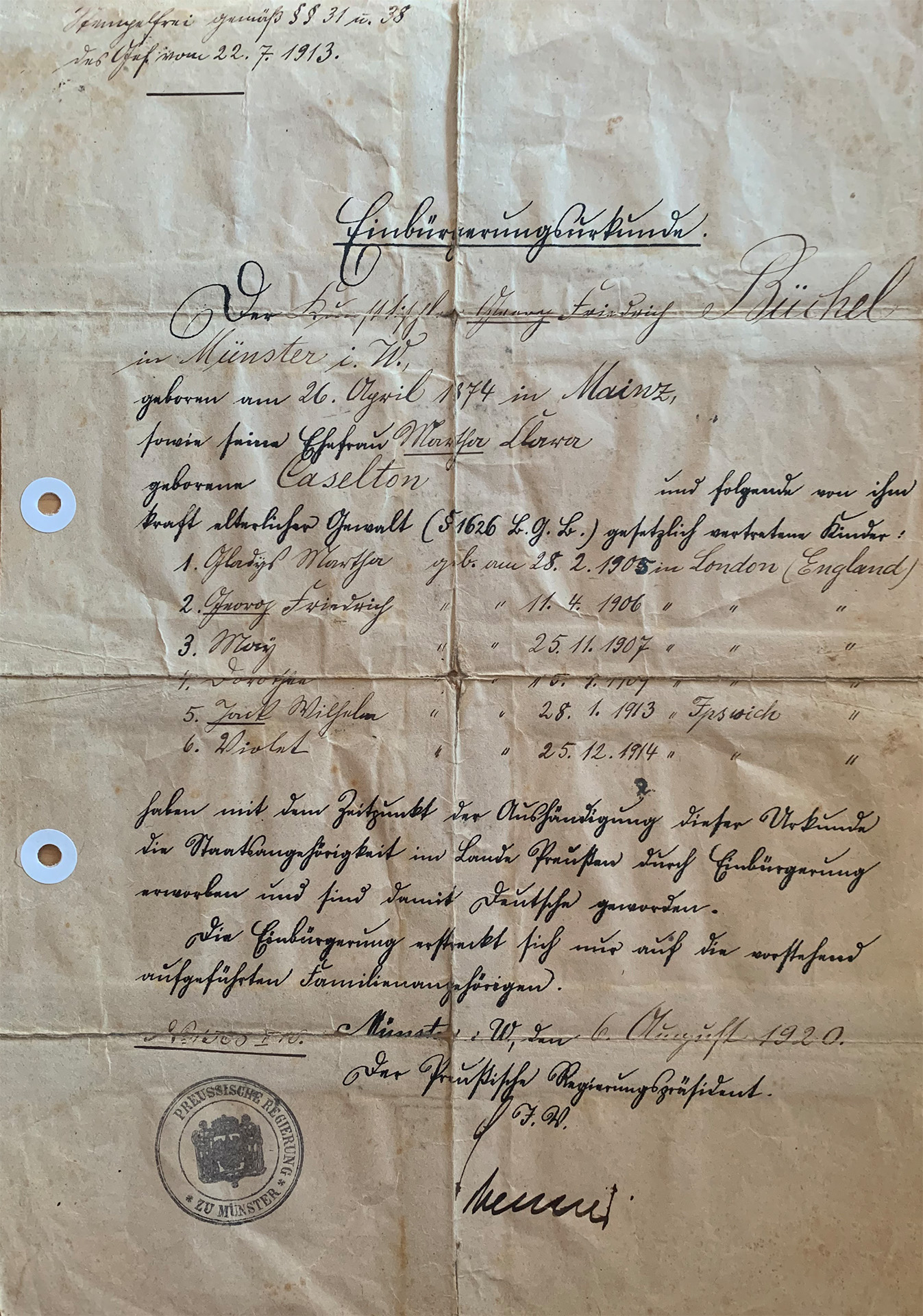

Viele der über 70.000 Opfer der »Aktion T4« hatten keine deutsche Staatsbürgerschaft oder waren im Ausland geboren und mit einer/einem Deutschen verheiratet, beispielsweise die Britin Martha Büchel (geb. Caselton).

Viele Opfer der Aktion T4 sind Ausländer.

Sie kommen nicht aus Deutschland.

Sie sind in einem anderen Land geboren.

Oder sie haben

keine deutsche Staats-Bürgerschaft.

Oder sie haben einen Deutschen geheiratet.

So ist es auch bei Martha Büchel.

Sie kommt aus England.

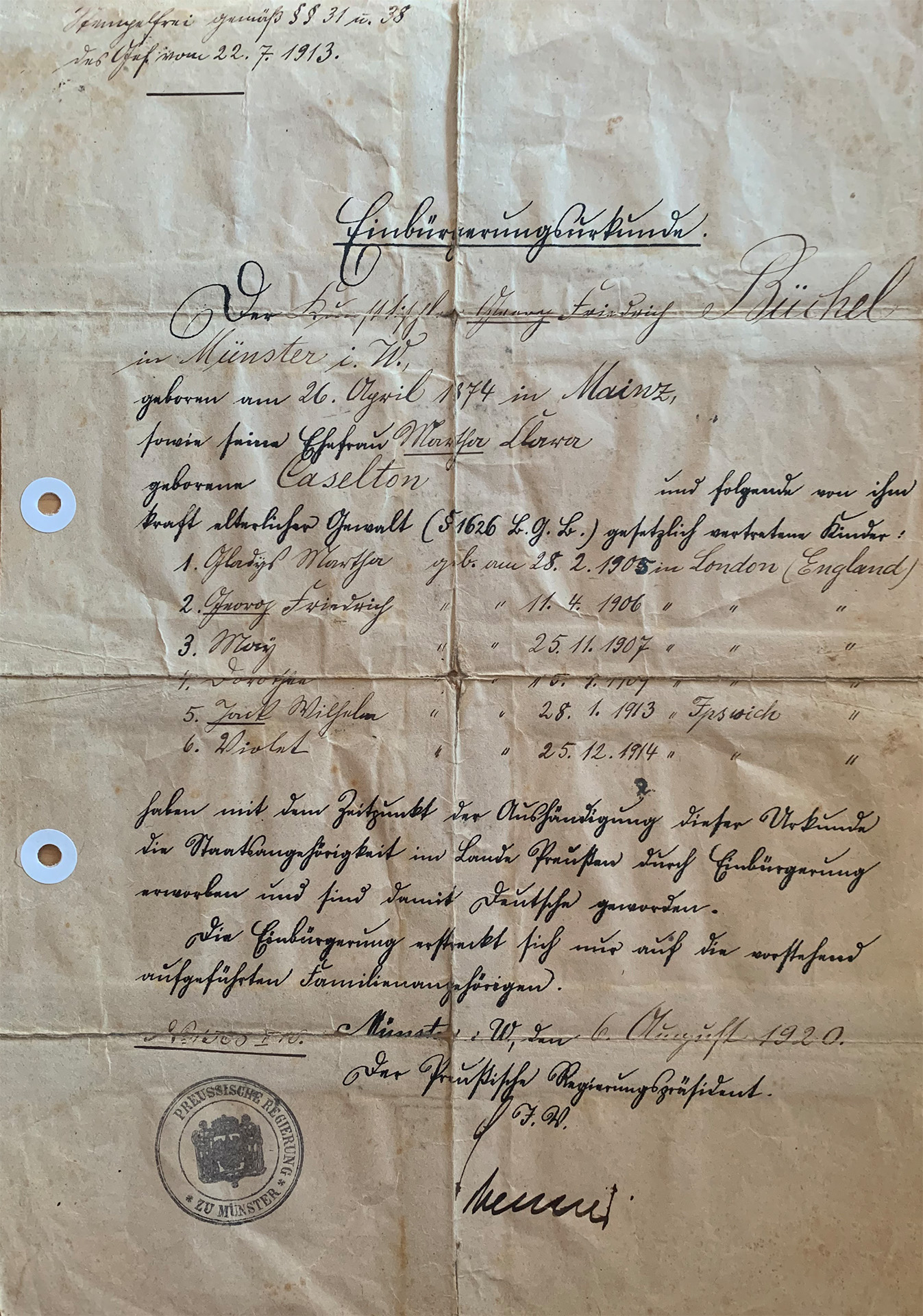

Einbürgerungsurkunde Familie Büchel, 6.8.1920.

Privatsammlung Günter Ahlers.

Martha Büchel war in London (Großbritannien) geboren und aufgewachsen. Sie gehörte zu mindestens 13 Frauen und Männern mit britischer Herkunft, die Opfer der »Aktion T4« wurden. Sie war mit dem berühmten deutschen Kunsttischler Georg Büchel verheiratet, der nach der Internierungszeit und dem verlorenen Ersten Weltkrieg in Großbritannien keine Zukunft mehr hatte. Sie wurde am 12. Mai 1941 in der Tötungsanstalt Hadamar ermordet.

Martha Büchel ist in London geboren.

Sie ist Engländerin.

Sie wird bei der Aktion T4 ermordet.

Es gibt mehr als 13 englische Opfer

bei der Aktion T4.

Martha Büchel hat einen deutschen Ehe-Mann.

Es ist der Tischler Georg Büchel.

Die beiden leben in England.

Dann ist der Erste Weltkrieg.

Georg Büchel kommt in England

in ein Gefangenen-Lager für Deutsche.

Dann ist der Erste Weltkrieg vorbei.

Georg Büchel bekommt keine Arbeit mehr

in England.

Darum gehen Georg und Martha

nach Deutschland.

Martha Büchel wird Deutsche.

Sie stirbt am 12. Mai 1941.

»AKTION T4«

As part of »Aktion T4«, sick people who had been in an institution for more than five years, were considered unfit for work and had little contact with relatives were to be murdered. 483 patients were transferred from Lüneburg, even though they did not fulfil these requirements. 479 of them were murdered. All were asphyxiated with carbon monoxide. The murder was not kept secret and there was opposition from the Ministry of Justice, families and the Catholic Church. In August 1941, the National Socialists officially stopped »Aktion T4«.

All the patients travelled on trains from Lüneburg station to the »Aktion T4« institutions. Lüneburg railway station, 1939.

StadtALg, BS, Pos-19249.

Transport of patients from the Liebenau asylum, August 1940.

Liebenau Foundation.

The 483 patients from Lüneburg were transferred to the Brandenburg and Pirna-Sonnenstein killing centres and the Herborn intermediate hospital by passenger train. Reichspostbuses were only used for the transfer from the Herborn intermediate hospital to the Hadamar killing centre.

»Discussed the issue of the tacit liquidation of the mentally ill with Bouhler. 80,000 are gone, 60,000 still have to go. That’s hard work, but it’s also necessary. And it has to be done now. Bouhler is the right man for the job.«

Diary entry by Joseph Goebbels dated 22 February 1941, quoted from Ralf Georg Reuth (ed.): Joseph Goebbels Tagebücher 1924 – 1945, here vol. 4 1940 – 1942, Munich 1992.

150 Jewish patients from a total of 25 institutions, including Isidor Seelig and Iwan Alexander, were transferred from the provinces of Hanover and Westphalia to the Wunstorf institution and nursing home in September 1940. Eight Jewish patients had already been accommodated in Wunstorf. On 27 September 1940, a total of 158 Jewish patients were transferred from Wunstorf to the Brandenburg killing centre, where they were murdered with gas.

Extract from the list of Jewish patients transferred, September 1940.

NLA Hannover Hann. 155 Wunstorf Acc. 38/84 No. 10.

»I would also like to point out that the accommodation of the patients in

Wunstorf is provided in the simplest form (straw hut without straw sacks) in the part of the institution recently vacated by the military and previously used as a reserve hospital.«

Chief President of the Province of Hanover to the Reich Minister of the Interior. Quoted from: Asmus Finzen: Mass murder without guilt, Bonn 1996.

On 7 March 1941, 122 patients were transferred from Lüneburg to the Pirna-Sonnenstein killing centre as part of »Aktion T4«. They were accompanied by personnel from the Berlin »T4-Zentrale«. They travelled by train. To do this, they had to walk to Lüneburg railway station. There, two carriages were attached to a passenger train. The patients were taken directly to Pirna (Saxony) and had to walk from the station to the killing centre again after their arrival.

Note: Concerning the transfer of mentally ill patients, ca. 1940.

Copy ArEGL.

These requirements had to be met during installation.

After arriving at the Pirna-Sonnenstein institution, the patients were examined and taken to a changing room. They had to undress. From there they were taken to the gas chamber. Behind the gas chamber were two ovens in which the victims were cremated. Corpse burners simply tipped the ashes onto the slope of the Elbe behind the institution.

Postcard, Pirna with Sonnenstein Castle (top left), 1923.

ArEGL 99.

August Golla (right) in the port of Wesermünde (Bremerhaven), postcard dated 1 February 1928.

Privately owned by Angelika Beltz.

The transfer to Pirna-Sonnenstein only affected male patients. One of them was August Golla. He came from Wesermünde (now Bremerhaven). August Golla worked as a net maker and was close to the Communist Party. This repeatedly led to conflicts with his father. In November 1936, August Golla behaved strangely and was hospitalised. From there he was transferred to the Lüneburg institution and nursing home.

Carl Riemann was a police officer in Hamburg. As he was married to a Jewish woman 15 years his junior, he was »mobbed« at work. This made him ill. The couple separated in 1934. He was admitted to the Friedrichsberg asylum (Hamburg), transferred to Hamburg-Langenhorn in 1935 and from there to Lüneburg in 1936. He remained here until his transfer to the Pirna-Sonnenstein killing centre. The official date of death was given as 24 March 1941.

Photo from Carl Riemann’s driving licence, 1922.

Hamburg State Archives 352-8/7 No. 22076 | Copy Martin Bähr.

Johannes Müller, around 1916.

Privately owned by Helga and Ludwig Müller.

Johannes Müller from Geestemünde (Bremerhaven) was a trained merchant. His father was a saddler and fitted out luxury ships. As a young man, Johannes Müller served in the First World War and then lived an apolitical, Christian, middle-class life. He fell ill in the 1930s. After his murder in Pirna-Sonnenstein, the family buried the urn with his ashes in the family grave, which still exists today.

On 9, 23 and 30 April 1941, a total of 357 patients from the Lüneburg institution and nursing home were transferred to the Herborn intermediate care facility as part of »Aktion T4«. These transfers were accompanied by employees of the Lüneburg institution and nursing home.

355 patients were transferred from Herborn to the Hadamar killing centre on 12, 21 and 28 May and 16 June 1941. There, the patients got off the buses in a garage. They were medically examined once again, taken to the gas chamber in the basement and murdered. Only two patients from Lüneburg survived because they were deemed sufficiently fit for work during the examination in the garage.

Hadamar killing centre with smoking chimney, 1941.

Archive of the State Welfare Association of Hesse, F 12/No. 192.

Passport of Heinrich Biester, issued on 13 April 1926.

ArEGL 127.

Heinrich Mund’s diary begins on 1 January 1926 and ends on 1 September 1944, describing the situation in the Lüneburg institution and nursing home at the time. There are hidden references to the murder of patients. He hints that too many children were dying in the institution and nursing home, which he had to bury as a chaplain. His concern about the transfer of his nephew Heinrich Biester and his indignation at his sudden death are also reflected in the diary.

Heinrich Mund 1871 – 1945. Diary notes from the years 1926, 1935 and 1937 – 1945, transcript and extract, p. 116.

ArEGL 161.

Heinrich Mund, before 1945.

Private collection, Mund family.

HEINRICH BIESTER (1901 – 1941)

Group photo of the Biester family. Heinrich Biester is standing in the back row, second from the right. To his left is his father, Hanover, 1925.

Privately owned by the Biester family.

Heinrich Biester grew up in Hanover-List. He wanted to become a musician and studied music and singing in Hanover and Vienna from 1924. He planned to study in the USA. But then he fell ill and returned home in 1926. His condition did not improve and he was admitted to the Lüneburg institution and nursing home in 1927. His uncle, Heinrich Mund, had been the chaplain there since 1907. He was supposed to look after his nephew. Heinrich Biester took part in the church services at the institution and played the violin there. But this did not protect him. He was murdered in the Hadamar killing centre on 21 May 1941. His relatives immediately suspected that a crime had been committed. The Christian family decided not to have the urn with his supposed ashes transferred and buried at home.

»Letter of consolation« from the Hadamar institution and nursing home to Emma Piske about the death of Elfa Seipel, dated 10 June 1941.

Privately owned by Ulla Bucarey.

»Letter of consolation« from the Hadamar institution and nursing home about the death of Heinrich Biester to his father Heinrich Biester dated 12 June 1941.

ArEGL 127.

»Letter of consolation« from the Hadamar institution and nursing home about the death of Anna Wichern to her mother Anna Wichern dated 27 June 1941.

ArEGL 127.

The relatives were informed of the »unexpected« death 10 to 20 days after the murder with a »consolation letter« that always had the same wording. The cause was just as fictitious as the date of death. By postponing the death to a later date, care allowances could still be paid for the deceased. This was used to pay for the murders.

Work by Gustav Sievers. Untitled, undated, pencil, watercolours on carbon paper.

Prinzhorn Collection Inv. no. 4332d.

Carl Langhein, before 1905.

From: Adolf von Oechelhäuser: Geschichte der Grossh. Badische Akademie der bildenden Künste, Karlsruhe 1904.

Advertising postcard by Carl Langhein, Valuable flotsam and jetsam Kupferberg Gold, lithograph, before 1927.

ArEGL 187.

Among the victims of »Aktion T4« were many artists and creative people whose works were devalued. One of them was Gustav Sievers, whose works are now preserved in the Prinzhorn Collection. Erich Seer was a successful graphic artist before he fell ill. Carl Langhein was also honoured as an artist and lithographer during his lifetime. He was awarded the title of professor in 1906 and founded the Hanseatic Art Publishers in 1918.

The collage shows a woman dressed as a harlequin sitting on a bar stool and blowing soap bubbles with the help of a pipe. There are three other pictures in the same style. The graphic designer and artist Erich Seer (1894 – 1941) glued them together using different coloured silk and black cardboard. He was a patient in Lüneburg from 1938 and was murdered in the Pirna-Sonnenstein killing centre on 7 March 1941.

Collage by Erich Seer, before 1941.

ArEGL 184.

Compared to men, women were more often the victims of murder of the sick. Their illnesses were often caused by pregnancy or childbirth, and sometimes they were victims of marital violence. As they usually had not learnt a profession, they were considered »useless« and »unworthy of life«.

Elsa and Heinrich Spartz (centre), around 1911.

Private property Maria Kiemen/Matthias Spartz.

Christine Sauerbrey, before 1914.

Privately owned by Traute Konietzko.

Agnes Fiebig (later Timme), 1929.

Privately owned by Sabine Röhrs.

Half of the female victims of »Aktion T4« were married. Elsa Spartz’s husband was the head doctor at St Mary’s Hospital in Hamburg. Although he knew about the murder of the sick, he did not save his wife. Christine Sauerbrey remained faithful to her husband when he was politically persecuted. When she fell ill, he divorced her. When Agnes Timme fell ill after the birth of her fourth child, her husband no longer looked after their children. They were placed in a care home.

Even a well-to-do, middle-class background and the private assumption of costs for a stay in an institution did not protect against transfer to a killing centre. Sick people from middle-class backgrounds were sometimes unwilling to do hours of hard physical labour in the fields, in the peeling shed or in the laundry. Sick people who refused were therefore more likely to be transferred to a killing centre.

Irmgard Ruschenbusch, around 1917.

Privately owned by Michael Schade.

Irmgard Ruschenbusch was the daughter of a doctor and came from a free Christian family that had produced many pastors and missionaries. Her background did not save her from being murdered.

Many of the more than 70,000 victims of »Aktion T4« did not have German citizenship or were born abroad and married to a German, for example the British woman Martha Büchel (née Caselton).

Naturalisation certificate of the Büchel family, 6.8.1920.

Private collection Günter Ahlers.

Martha Büchel was born and grew up in London (Great Britain). She was one of at least 13 women and men of British origin who were victims of »Aktion T4«. She was married to the famous German cabinetmaker Georg Büchel, who had no future in Great Britain after being interned and losing the First World War. She was murdered in the Hadamar killing centre on 12 May 1941.

»AKTION T4«

W ramach »Aktion T4« zamordowani mieli zostać chorzy, którzy przebywali w placówce dłużej niż pięć lat, zostali uznani za niezdolnych do pracy i mieli niewielki kontakt z krewnymi. 483 pacjentów zostało przeniesionych z Lüneburga, mimo że nie spełniali tych wymagań. 479 z nich zostało zamordowanych. Wszyscy zostali uduszeni tlenkiem węgla. Morderstwo nie było utrzymywane w tajemnicy i spotkało się ze sprzeciwem Ministerstwa Sprawiedliwości, rodzin i Kościoła katolickiego. W sierpniu 1941 r. narodowi socjaliści oficjalnie przerwali »Aktion T4«.

Wszyscy pacjenci podróżowali pociągami z dworca w Lüneburgu do instytucji »Aktion T4«. Dworzec kolejowy w Lüneburgu, 1939 r.

StadtALg, BS, Pos-19249.

Transport pacjentów z przytułku Liebenau, sierpień 1940 r.

Fundacja Liebenau.

483 pacjentów z Lüneburga zostało przetransportowanych do ośrodków zagłady w Brandenburgu i Pirna-Sonnenstein oraz do szpitala pośredniego w Herborn pociągiem osobowym. Reichspostbusy były używane tylko do transportu ze szpitala pośredniego Herborn do ośrodka zagłady Hadamar.

»Omówiłem z Bouhlerem kwestię cichej likwidacji chorych psychicznie. 80 000 odeszło, 60 000 wciąż musi odejść. To ciężka praca, ale konieczna. I trzeba to zrobić teraz. Bouhler jest właściwym człowiekiem do tego zadania.«

Wpis w dzienniku Josepha Goebbelsa z 22 lutego 1941 r., cytowany za Ralf Georg Reuth (red.): Joseph Goebbels Tagebücher 1924 – 1945, tu t. 4 1940 – 1942, Monachium 1992.

150 żydowskich pacjentów z łącznie 25 instytucji, w tym Isidor Seelig i Iwan Alexander, zostało przeniesionych z prowincji Hanower i Westfalia do instytucji i domu opieki w Wunstorf we wrześniu 1940 roku. Ośmiu żydowskich pacjentów było już wcześniej zakwaterowanych w Wunstorf. W dniu 27 września 1940 r. 158 żydowskich pacjentów zostało przeniesionych z Wunstorf do ośrodka zagłady w Brandenburgu, gdzie zostali zamordowani przy użyciu gazu.

Fragment listy przeniesionych pacjentów żydowskich, wrzesień 1940 r.

NLA Hannover Hann. 155 Wunstorf Acc. 38/84 n. 10.

»Chciałbym również zauważyć, że zakwaterowanie pacjentów w

Wunstorf jest zapewnione w najprostszej formie (słomiana chata bez worków na słomę) w części instytucji niedawno zwolnionej przez wojsko i wcześniej używanej jako szpital rezerwowy.«

Nadprezydent prowincji Hanower do ministra spraw wewnętrznych Rzeszy. Cyt. za: Asmus Finzen: Masowe morderstwa bez winy, Bonn 1996.

7 marca 1941 r. 122 pacjentów zostało przetransportowanych z Lüneburga do ośrodka zagłady Pirna-Sonnenstein w ramach „Akcji T4”. Towarzyszył im personel berlińskiego „T4-Zentrale”. Podróżowali pociągiem. Aby to zrobić, musieli przejść pieszo do stacji kolejowej Lüneburg. Tam dwa wagony zostały doczepione do pociągu osobowego. Pacjenci zostali przewiezieni bezpośrednio do Pirny (Saksonia), a po przybyciu musieli ponownie przejść pieszo ze stacji do ośrodka zagłady.

Uwaga: Dotyczy przenoszenia pacjentów chorych psychicznie, ok. 1940 r.

Kopia ArEGL.

Wymagania te musiały zostać spełnione podczas instalacji.

Po przybyciu do placówki Pirna-Sonnenstein pacjenci byli badani i zabierani do szatni. Musieli się rozebrać. Stamtąd zabierano ich do komory gazowej. Za komorą gazową znajdowały się dwa piece, w których ofiary były kremowane. Palarnie zwłok po prostu wysypywały popiół na zbocze Łaby za zakładem.

Pocztówka, Pirna z zamkiem Sonnenstein (u góry po lewej), 1923 r.

ArEGL 99.

August Golla (po prawej) w porcie Wesermünde (Bremerhaven), pocztówka z 1 lutego 1928 r.

Prywatna własność Angeliki Beltz.

Przeniesienie do Pirna-Sonnenstein dotyczyło tylko pacjentów płci męskiej. Jednym z nich był August Golla. Pochodził z Wesermünde (obecnie Bremerhaven). August Golla pracował jako producent sieci i był blisko partii komunistycznej. Wielokrotnie prowadziło to do konfliktów z ojcem. W listopadzie 1936 r. August Golla zachowywał się dziwnie i trafił do szpitala. Stamtąd został przeniesiony do zakładu i domu opieki w Lüneburgu.

Carl Riemann był policjantem w Hamburgu. Ponieważ był żonaty z młodszą o 15 lat Żydówką, w pracy był „prześladowany”. Doprowadziło go to do choroby. Para rozstała się w 1934 roku. Został przyjęty do azylu Friedrichsberg (Hamburg), przeniesiony do Hamburg-Langenhorn w 1935 roku, a stamtąd do Lüneburga w 1936 roku. Pozostał tu do czasu przeniesienia do ośrodka zagłady Pirna-Sonnenstein. Jako oficjalną datę śmierci podano 24 marca 1941 roku.

Zdjęcie z prawa jazdy Carla Riemanna, 1922 r.

Archiwum Państwowe w Hamburgu 352-8/7 n. 22076 | Kopia Martin Bähr.

Johannes Müller, około 1916 r.

Prywatna własność Helgi i Ludwiga Müllerów.

Johannes Müller z Geestemünde (Bremerhaven) był wykształconym kupcem. Jego ojciec był rymarzem i wyposażał luksusowe statki. Jako młody człowiek Johannes Müller służył w I wojnie światowej, a następnie prowadził apolityczne, chrześcijańskie życie klasy średniej. Zachorował w latach trzydziestych XX wieku. Po jego zabójstwie w Pirna-Sonnenstein rodzina pochowała urnę z jego prochami w rodzinnym grobie, który istnieje do dziś.

W dniach 9, 23 i 30 kwietnia 1941 r. łącznie 357 pacjentów z zakładu i domu opieki w Lüneburgu zostało przeniesionych do zakładu opieki pośredniej w Herborn w ramach »Aktion T4«. Przeniesieniom towarzyszyli pracownicy zakładu i domu opieki w Lüneburgu.

355 pacjentów zostało przetransportowanych z Herborn do ośrodka zagłady Hadamar w dniach 12, 21 i 28 maja oraz 16 czerwca 1941 roku. Tam pacjenci wysiadali z autobusów w garażu. Zostali ponownie przebadani medycznie, zabrani do komory gazowej w piwnicy i zamordowani. Tylko dwóch pacjentów z Lüneburga przeżyło, ponieważ podczas badania w garażu uznano ich za wystarczająco zdolnych do pracy.

Centrum zabójstw Hadamar z dymiącym kominem, 1941 r.

Archiwum Państwowego Związku Opieki Społecznej Hesji, F 12/n. 192.

Dziennik Heinricha Munda rozpoczyna się 1 stycznia 1926 r. i kończy 1 września 1944 r., opisując sytuację w zakładzie i domu opieki w Lüneburgu w tym czasie. Znajdują się w nim ukryte odniesienia do zabójstw pacjentów. Sugeruje, że w zakładzie i domu opieki umierało zbyt wiele dzieci, które musiał pochować jako kapelan. Jego zaniepokojenie przeniesieniem siostrzeńca Heinricha Biestera i oburzenie z powodu jego nagłej śmierci są również odzwierciedlone w dzienniku.

Heinrich Mund 1871 – 1945. Notatki z pamiętnika z lat 1926, 1935 i 1937-1945, transkrypcja i wyciąg, s. 116.

ArEGL 161.

Heinrich Mund, przed 1945 r.

Kolekcja prywatna, rodzina Mund.

HEINRICH BIESTER (1901 – 1941)

Zdjęcie grupowe rodziny Biesterów. Heinrich Biester stoi w tylnym rzędzie, drugi od prawej. Po jego lewej stronie stoi jego ojciec, Hanower, 1925 r.

Prywatna własność rodziny Biester.

Heinrich Biester dorastał w Hanowerze-Liście. Chciał zostać muzykiem i od 1924 r. studiował muzykę i śpiew w Hanowerze i Wiedniu. Planował studiować w USA. Jednak zachorował i wrócił do domu w 1926 roku. Jego stan nie poprawił się i w 1927 r. został przyjęty do zakładu i domu opieki w Lüneburgu. Jego wuj, Heinrich Mund, był tam kapelanem od 1907 roku. Miał on opiekować się swoim bratankiem. Heinrich Biester brał udział w nabożeństwach w zakładzie i grał tam na skrzypcach. Ale to go nie ochroniło. Został zamordowany w ośrodku zagłady Hadamar 21 maja 1941 roku. Jego krewni od razu podejrzewali, że popełniono zbrodnię. Chrześcijańska rodzina postanowiła nie przenosić urny z jego domniemanymi prochami i pochować ją w domu.

»List pocieszenia« z zakładu i domu opieki Hadamar do Emmy Piske w związku ze śmiercią Elfy Seipel, datowany na 10 czerwca 1941 r.

Prywatna własność Ulli Bucarey.

»List pocieszenia« z zakładu i domu opieki Hadamar o śmierci Heinricha Biestera do jego ojca Heinricha Biestera z 12 czerwca 1941 r.

ArEGL 127.

»List pocieszenia« z zakładu i domu opieki Hadamar o śmierci Anny Wichern do jej matki Anny Wichern z 27 czerwca 1941 r.

ArEGL 127.

Krewni byli informowani o »nieoczekiwanej« śmierci od 10 do 20 dni po morderstwie za pomocą »listu pocieszenia«, który zawsze miał takie samo brzmienie. Przyczyna była tak samo fikcyjna jak data śmierci. Odkładając śmierć na później, można było nadal wypłacać zasiłki opiekuńcze dla zmarłego. W ten sposób płacono za morderstwa.

Praca Gustava Sieversa. Bez tytułu, bez daty, ołówek, akwarele na kalce.

Prinzhorn Collection n. inw. 4332d.

Carl Langhein, przed 1905 r.

Z: Adolf von Oechelhäuser: Geschichte der Grossh. Badische Akademie der bildenden Künste, Karlsruhe 1904.

Pocztówka reklamowa autorstwa Carla Langheina, Valuable flotsam and jetsam Kupferberg Gold, litografia, przed 1927.

ArEGL 187.

Wśród ofiar »Aktion T4« znalazło się wielu artystów i twórców, których dzieła zostały zdewaluowane. Jednym z nich był Gustav Sievers, którego prace znajdują się obecnie w Prinzhorn Collection. Erich Seer był odnoszącym sukcesy grafikiem, zanim zachorował. Carl Langhein również został uhonorowany jako artysta i litograf za życia. W 1906 roku otrzymał tytuł profesora, a w 1918 roku założył Hanzeatyckie Wydawnictwo Artystyczne.

Kolaż przedstawia kobietę przebraną za arlekina siedzącą na stołku barowym i dmuchającą bańki mydlane za pomocą fajki. W tym samym stylu utrzymane są trzy inne obrazy. Grafik i artysta Erich Seer (1894 – 1941) skleił je ze sobą przy użyciu różnokolorowego jedwabiu i czarnego kartonu. Od 1938 r. był pacjentem w Lüneburgu, a 7 marca 1941 r. został zamordowany w ośrodku zagłady Pirna-Sonnenstein.

Kolaż autorstwa Ericha Seera, przed 1941 r.

ArEGL 184.

W porównaniu z mężczyznami, kobiety częściej padały ofiarą zabójstw chorych. Ich choroby były często spowodowane ciążą lub porodem, a czasami były ofiarami przemocy małżeńskiej. Ponieważ zwykle nie uczyły się zawodu, uważano je za »bezużyteczne« i »niegodne życia«.

Elsa i Heinrich Spartz (w środku), około 1911 r.

Własność prywatna Maria Kiemen/Matthias Spartz.

Christine Sauerbrey, przed 1914 r.

Prywatna własność Traute Konietzko.

Agnes Fiebig (później Timme), 1929 r.

Prywatna własność Sabine Röhrs.

Połowa ofiar »Aktion T4« była zamężna. Mąż Elsy Spartz był głównym lekarzem w Szpitalu Mariackim w Hamburgu. Choć wiedział o mordowaniu chorych, nie uratował żony. Christine Sauerbrey pozostała wierna mężowi, gdy ten był prześladowany politycznie. Kiedy zachorowała, rozwiódł się z nią. Kiedy Agnes Timme zachorowała po urodzeniu czwartego dziecka, jej mąż nie zajmował się już ich dziećmi. Zostały one umieszczone w domu opieki.

Nawet zamożne pochodzenie z klasy średniej i prywatne pokrycie kosztów pobytu w placówce nie chroniło przed przeniesieniem do ośrodka zagłady. Chorzy wywodzący się z klasy średniej niekiedy nie byli skłonni do wielogodzinnej ciężkiej pracy fizycznej na polu, w obieralni czy pralni. Chorzy, którzy odmówili, byli zatem bardziej narażeni na przeniesienie do ośrodka zagłady.

Irmgard Ruschenbusch, około 1917 r.

Prywatna własność Michaela Schade.

Irmgard Ruschenbusch była córką lekarza i pochodziła z wolnej chrześcijańskiej rodziny, która wydała na świat wielu pastorów i misjonarzy. Jej pochodzenie nie uchroniło jej przed morderstwem.

Wiele z ponad 70 000 ofiar »Aktion T4« nie posiadało niemieckiego obywatelstwa lub urodziło się za granicą i poślubiło Niemca, na przykład Brytyjka Martha Büchel (z domu Caselton).

Świadectwo naturalizacji rodziny Büchel, 6.8.1920 r.

Kolekcja prywatna Günter Ahlers.

Martha Büchel urodziła się i dorastała w Londynie (Wielka Brytania). Była jedną z co najmniej 13 kobiet i mężczyzn brytyjskiego pochodzenia, którzy padli ofiarą »Aktion T4«. Była żoną słynnego niemieckiego stolarza Georga Büchela, który nie miał przyszłości w Wielkiej Brytanii po internowaniu i przegranej I wojnie światowej. Została zamordowana w ośrodku zagłady Hadamar 12 maja 1941 roku.