NFC zu H9

FORSCHUNG UND LETZTE KRIEGSJAHRE

Willi Baumert gab 1948 zu, dass er nach Berlin in die »Kanzlei des Führers« gefahren sei, um Ziel und Zweck der »Kinderfachabteilung« zu erfahren. Hierbei habe Hans Hefelmann ihm mitgeteilt, dass an den Kindern und Jugendlichen Ursachen von Beeinträchtigungen erforscht werden. Die Ergebnisse sollten zur Vorbeugung von Erkrankungen und Behinderungen beitragen. Außerdem sollte das »Gesetz zur Verhütung erbkranken Nachwuchses« verbessert werden.

FORSCHUNG UND LETZTE KRIEGS-JAHRE

Willi Baumert ist Arzt in der Kinder-Fachabteilung.

Nach dem Krieg im Jahr 1948 sagt er:

Ich bin in der Nazi-Zeit nach Berlin gefahren.

Denn ich wollte wissen,

warum es Kinder-Fachabteilungen gibt.

Ich habe in Berlin mit Hans Hefelmann gesprochen.

Er war Leiter vom Büro von Adolf Hitler.

Hans Hefelmann erzählte mir:

Kinder mit Behinderungen und Krankheiten sollen erforscht werden.

Die Forschung will wissen,

• warum die Kinder krank sind.

• warum die Kinder eine Behinderung haben.

Darum muss man Versuche

mit den Kindern machen.

Die Versuche machen wir

in den Kinder-Fachabteilungen.

Es soll keine Behinderungen mehr geben.

Es soll keine Krankheiten mehr geben.

Die Versuche mit Kindern sollen dabei helfen.

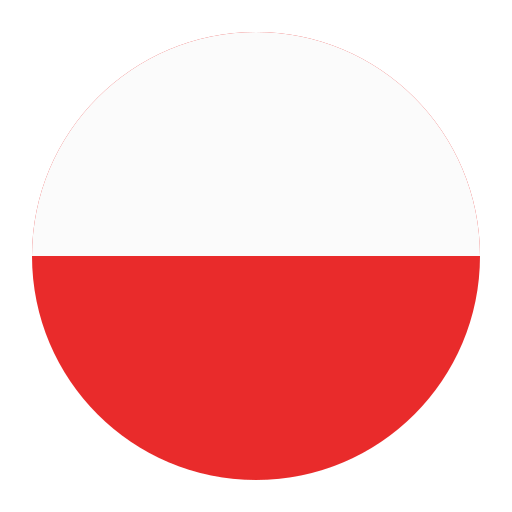

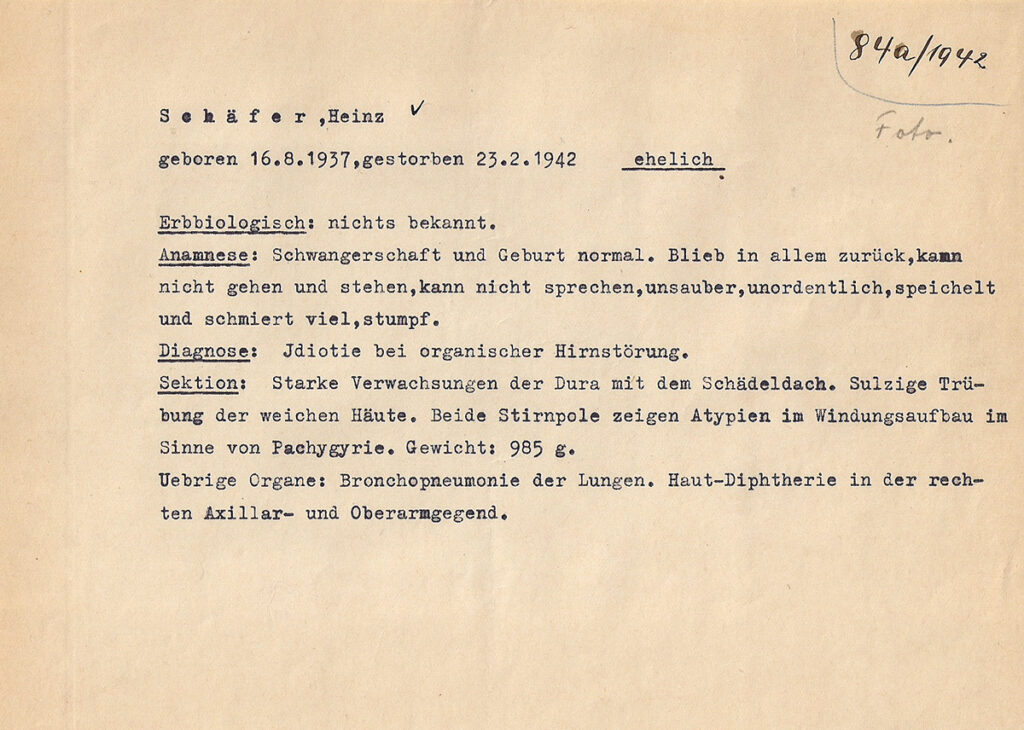

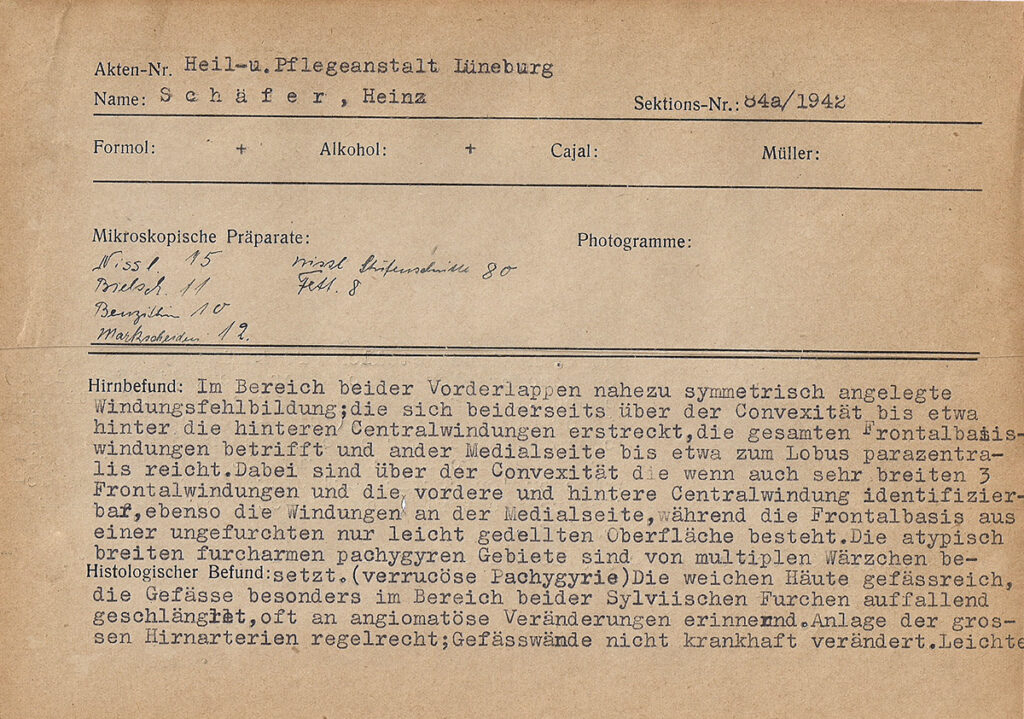

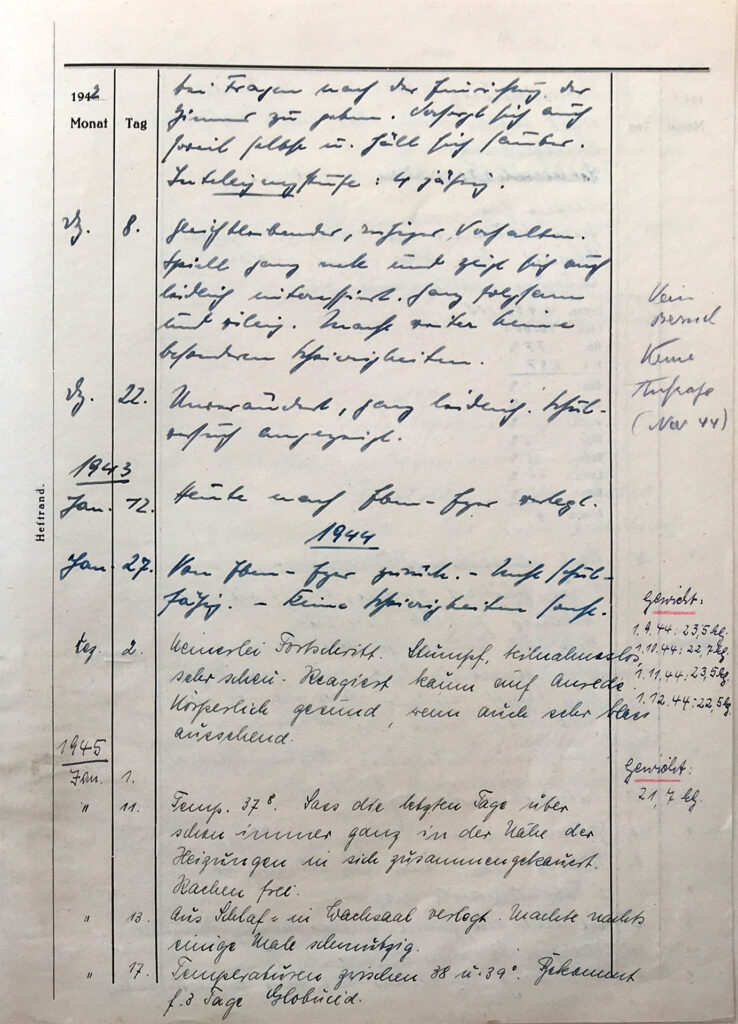

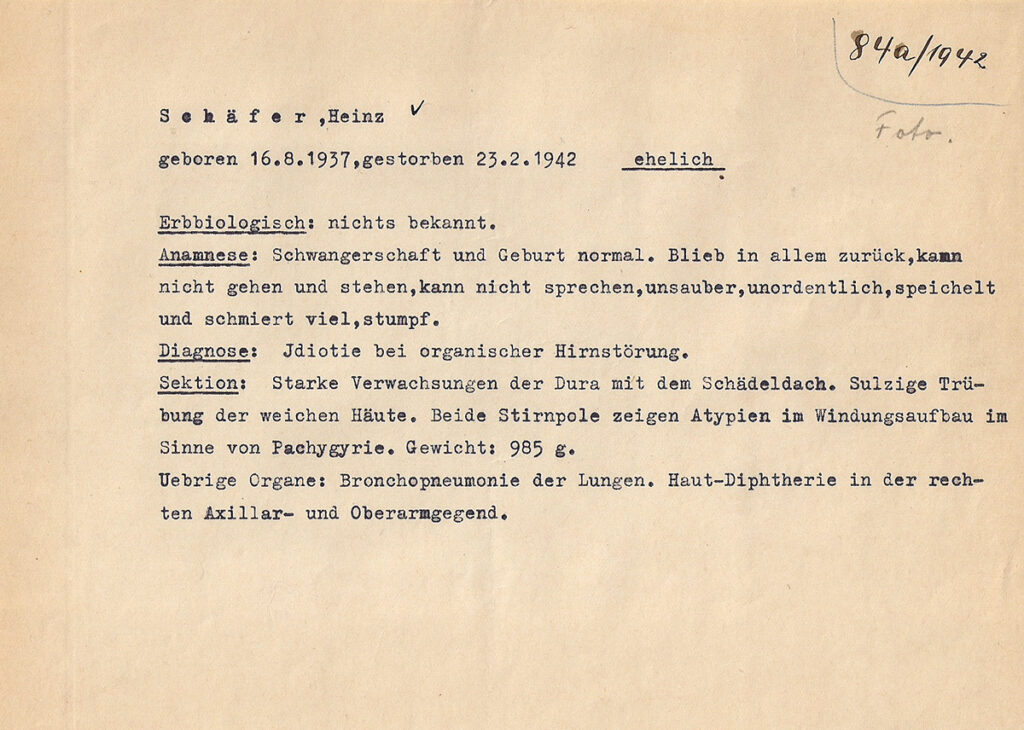

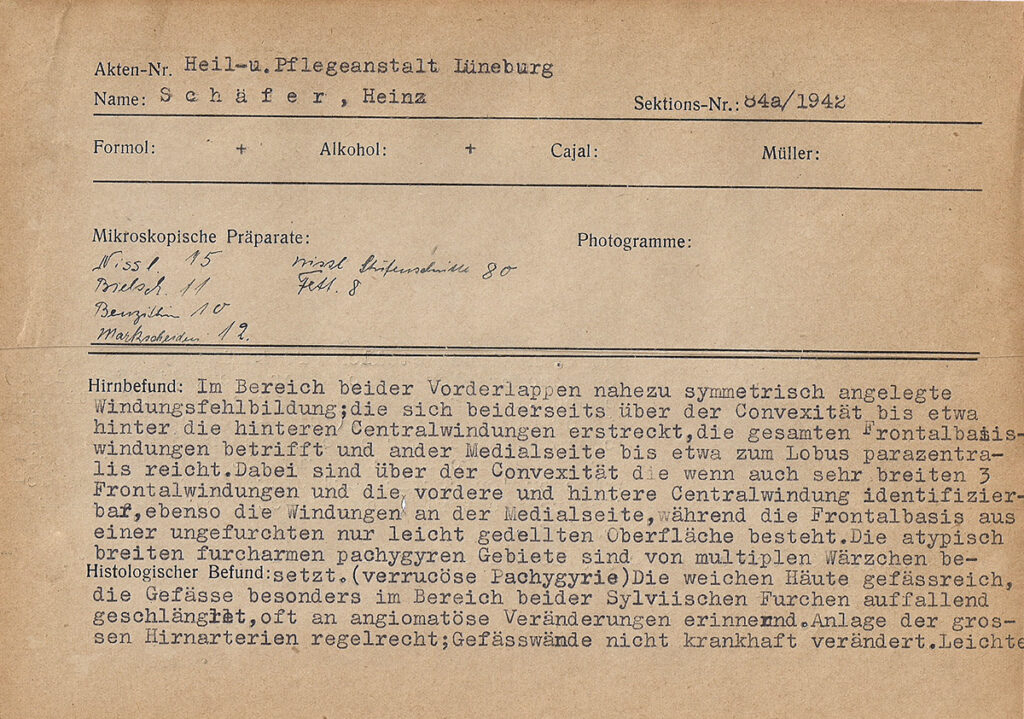

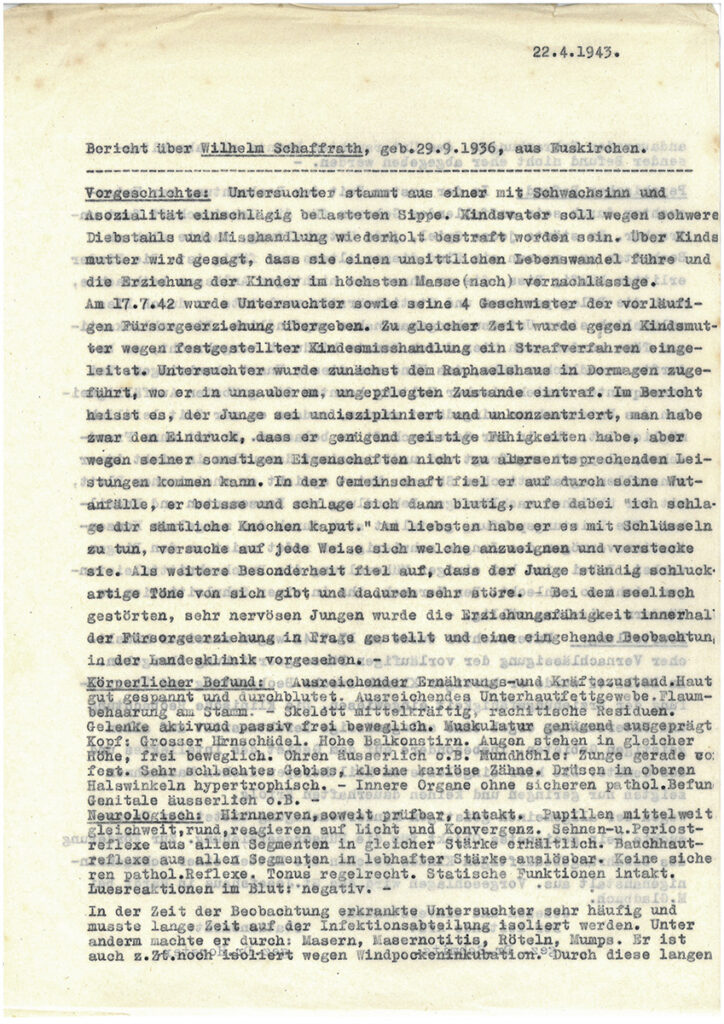

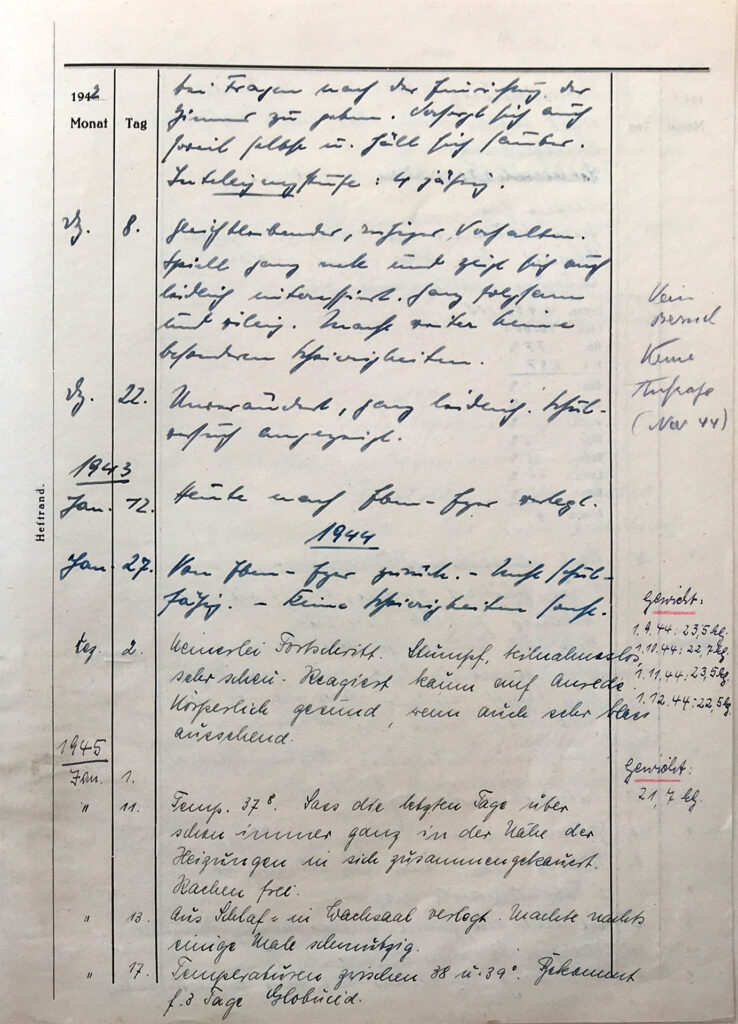

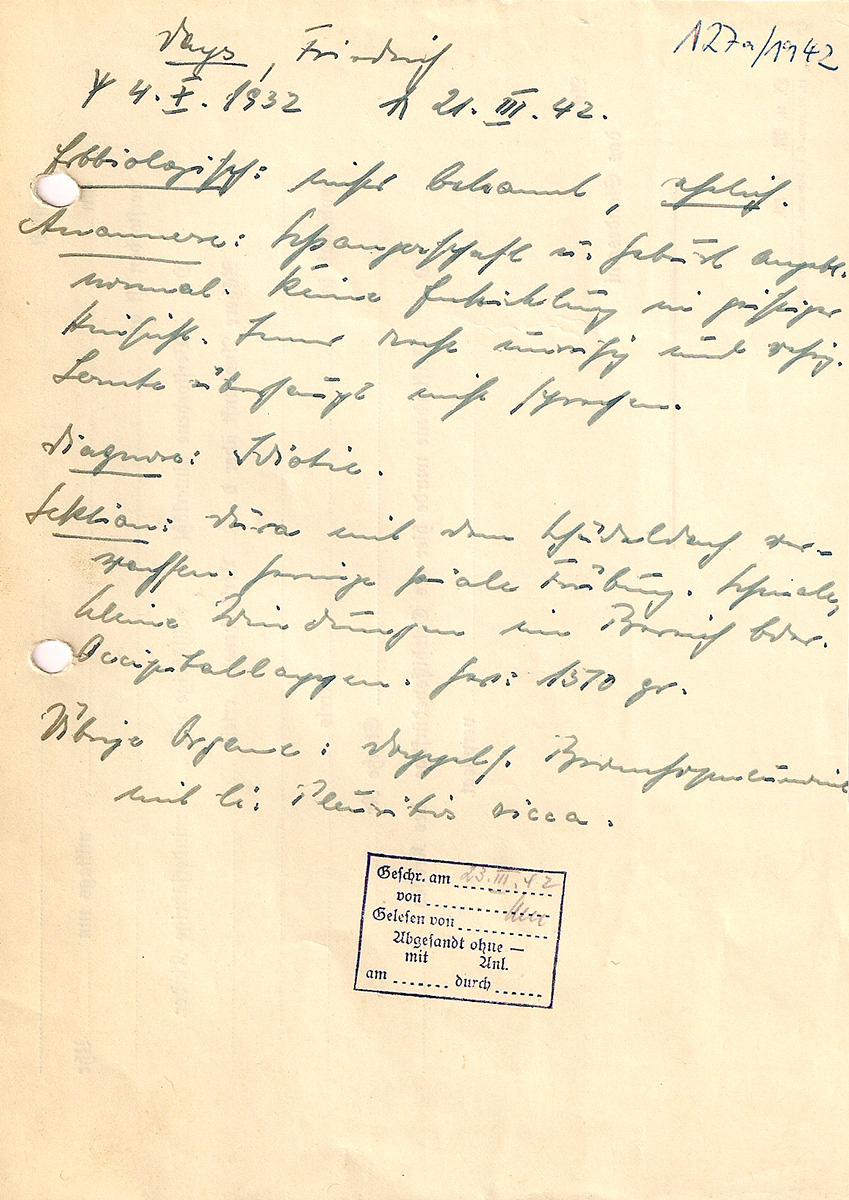

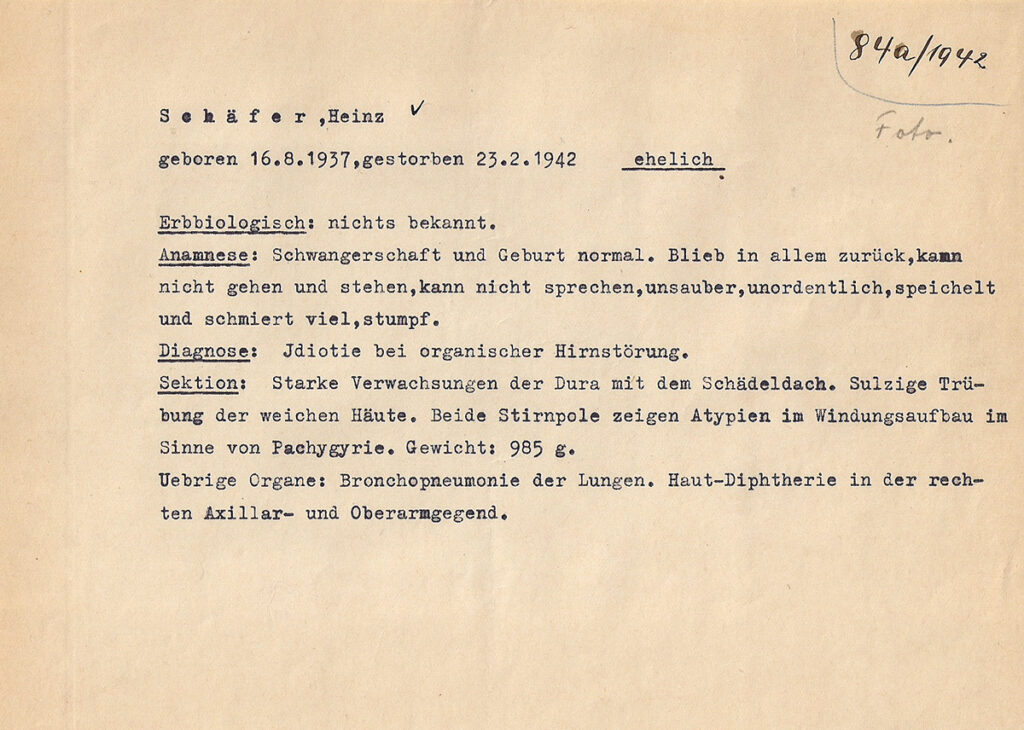

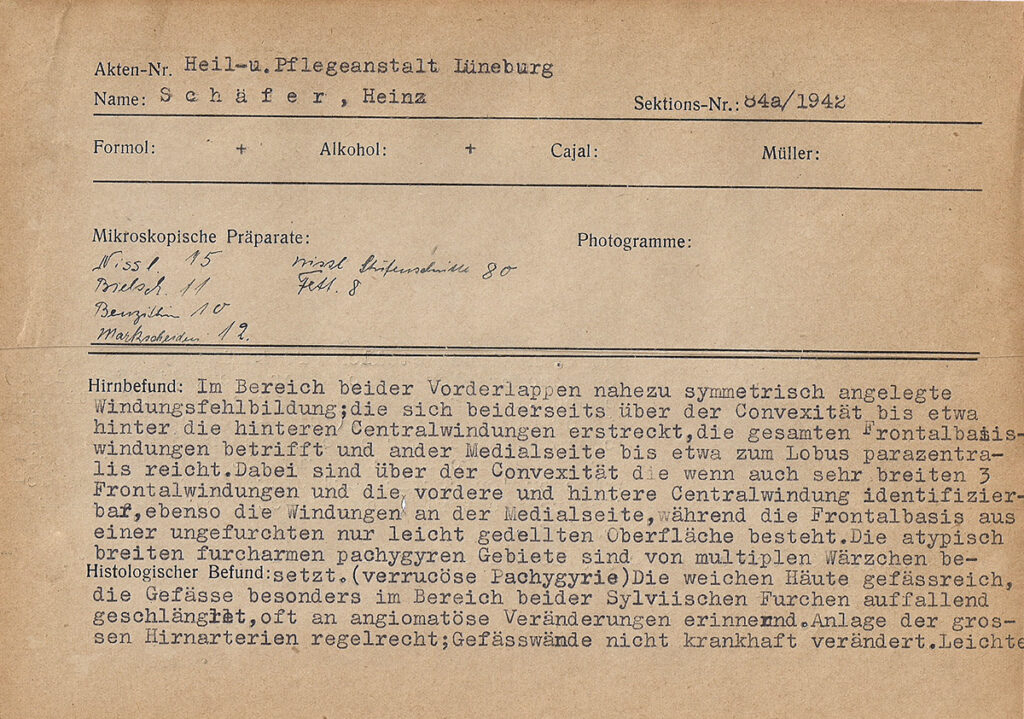

Auszug aus der Mitschrift der Leichenöffnung von 338 Kindern und Jugendlichen, in diesem Fall Friedrich Daps vom 23.3.1942.

PrivatbesitInstitut für Geschichte und Ethik der Medizin Hamburg.

Die Forschung erfolgte zum einen durch Beobachtung und Intelligenzprüfung. Zum anderen wurden die Kinder und Jugendlichen körperlich untersucht. Hierfür wurden Blut und Gehirnflüssigkeit abgenommen, aus den Kinderleichen die Organe entnommen. Im Keller von Haus 25 wurde ein Raum eingerichtet, in dem die Leichen geöffnet werden konnten. Willi Baumert führte 338 solcher Eingriffe durch und entnahm die Gehirne. Er untersuchte sie und schrieb alles auf.

Die Ärzte in der Kinder-Fachabteilung erforschen die Kinder:

• Sie beobachten die Kinder.

• Sie messen die Intelligenz von den Kindern.

• Sie prüfen das Denken von den Kindern.

• Sie prüfen,

wie fit der Körper von den Kindern ist.

• Sie untersuchen das Blut von den Kindern.

• Sie untersuchen das Gehirn-Wasser

von den Kindern.

Die Ärzte untersuchen auch tote Kinder.

Sie schneiden die Leichen von den Kindern auf.

Sie nehmen die Organe aus den Leichen raus.

Sie schneiden den Kopf auf und

nehmen das Gehirn raus.

Das alles passiert in Lüneburg

in einem Keller-Raum in Haus 25.

Der Arzt Willi Baumert macht das alles

Er macht das bei 338 Kinder-Leichen.

Und er schreibt alles auf.

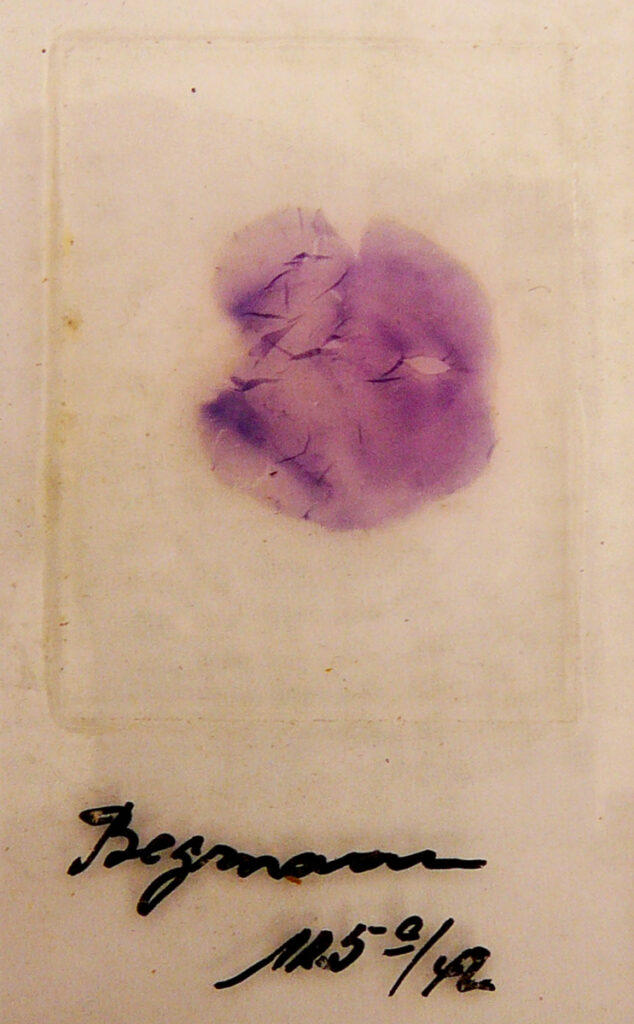

Viele Organe gab er an das Universitätsklinikum Hamburg-Eppendorf (etwa 37 Abgaben sind belegt). Dort wurden hauchdünne Schnitt-Präparate angefertigt. Als Willi Baumert im August 1944 wieder in den Kriegseinsatz musste, übernahm Max Bräuner die Entnahme und Untersuchung der Gehirne.

Willi Baumert gibt die Gehirne

von den toten Kindern weiter an andere Ärzte.

Er gibt die Gehirne von 37 toten Kindern

an das Krankenhaus in Hamburg-Eppendorf.

Die Ärzte im Krankenhaus in Hamburg untersuchen die Gehirne von den toten Kindern.

Sie schneiden die Gehirne in dünne Scheiben.

Dann können sie die Gehirne

unter einem Vergrößerungs-Glas untersuchen.

Willi Baumert ist ab dem Jahr 1944 nicht mehr

in Lüneburg.

Er muss als Arzt in den Krieg.

Max Bräuner übernimmt seine Aufgaben.

Jetzt untersucht er die Leichen von den Kindern.

Und er nimmt die Organe aus den Leichen heraus.Willi Baumert gibt die Gehirne

von den toten Kindern weiter an andere Ärzte.

Er gibt die Gehirne von 37 toten Kindern

an das Krankenhaus in Hamburg-Eppendorf.

Die Ärzte im Krankenhaus in Hamburg untersuchen die Gehirne von den toten Kindern.

Sie schneiden die Gehirne in dünne Scheiben.

Dann können sie die Gehirne

unter einem Vergrößerungs-Glas untersuchen.

Willi Baumert ist ab dem Jahr 1944 nicht mehr

in Lüneburg.

Er muss als Arzt in den Krieg.

Max Bräuner übernimmt seine Aufgaben.

Jetzt untersucht er die Leichen von den Kindern.

Und er nimmt die Organe aus den Leichen heraus.

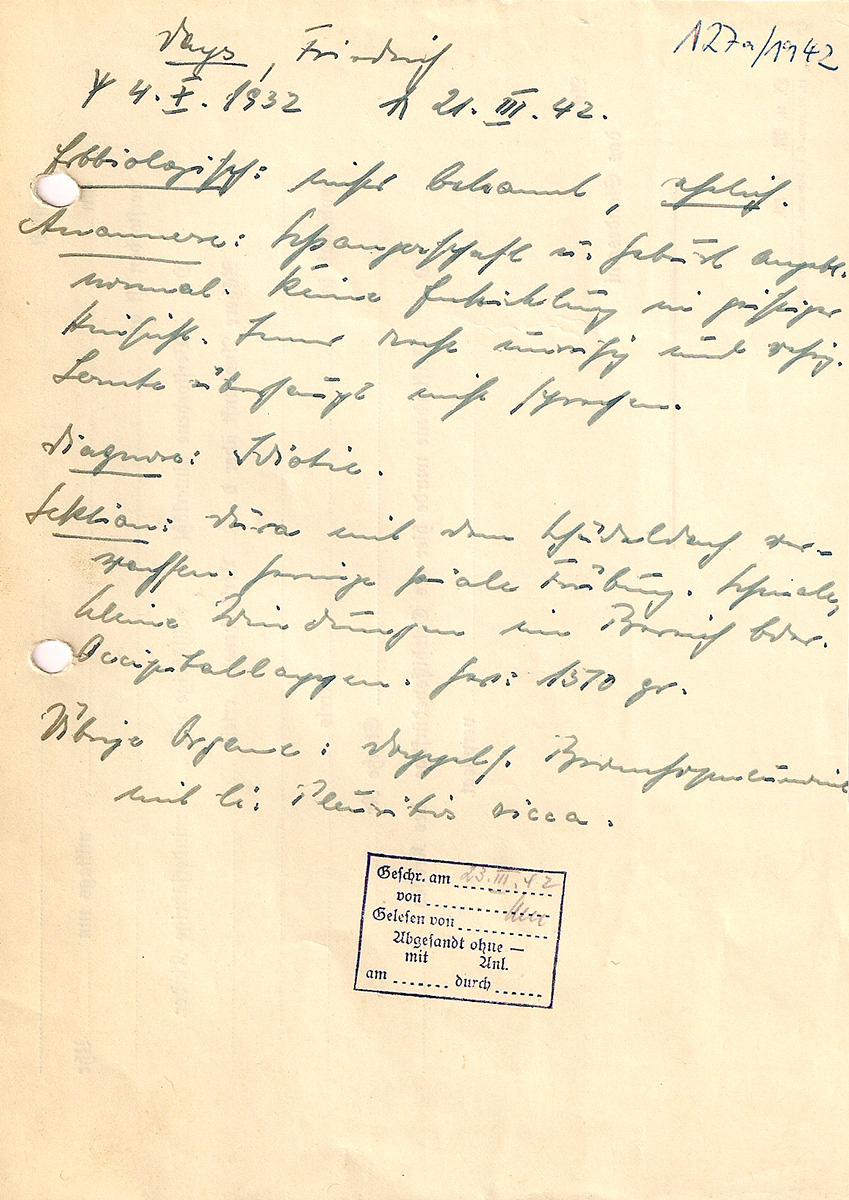

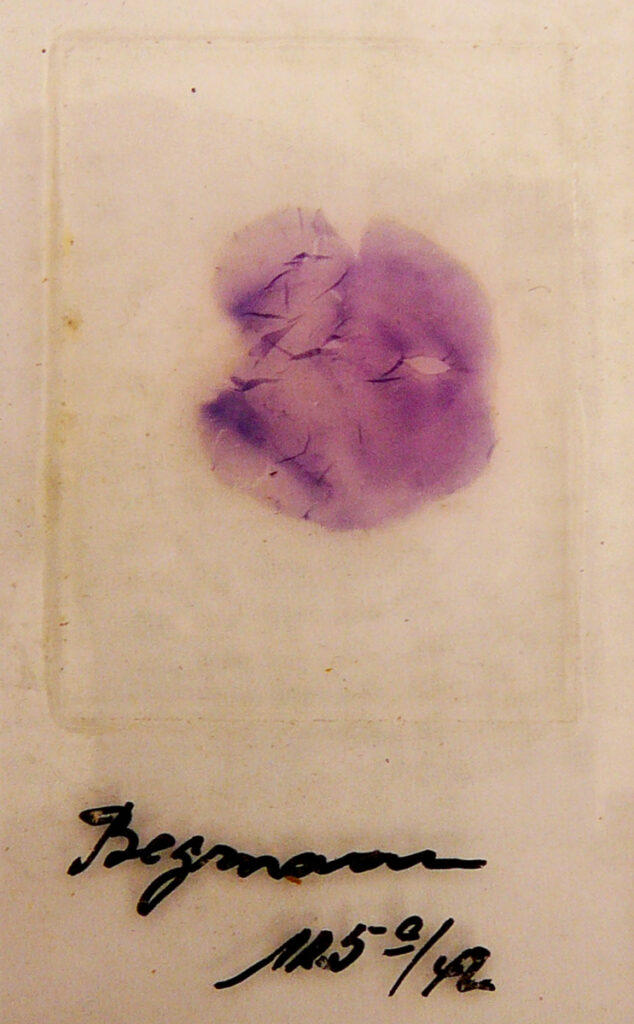

Objektträger mit Schnitt von Marianne Begemann, Universitätsklinikum Hamburg-Eppendorf (UKE), 1942.

Institut für Geschichte und Ethik der Medizin Hamburg.

Dies sind die Namen der Kinder und Jugendlichen, deren Gehirne und weitere Organe an die Universitätsklinik Hamburg-Eppendorf (UKE) abgegeben wurden:

Das sind die Namen von den Kindern,

die in Lüneburg ermordet werden.

Ihre Gehirne und Organe hat man

an das Krankenhaus in Hamburg gegeben.

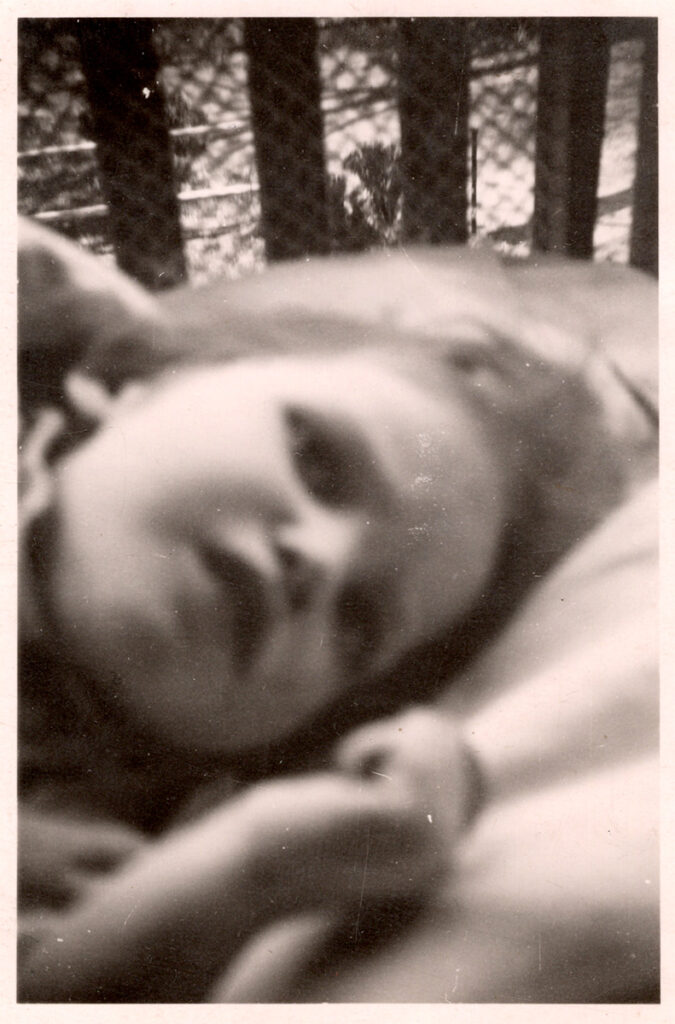

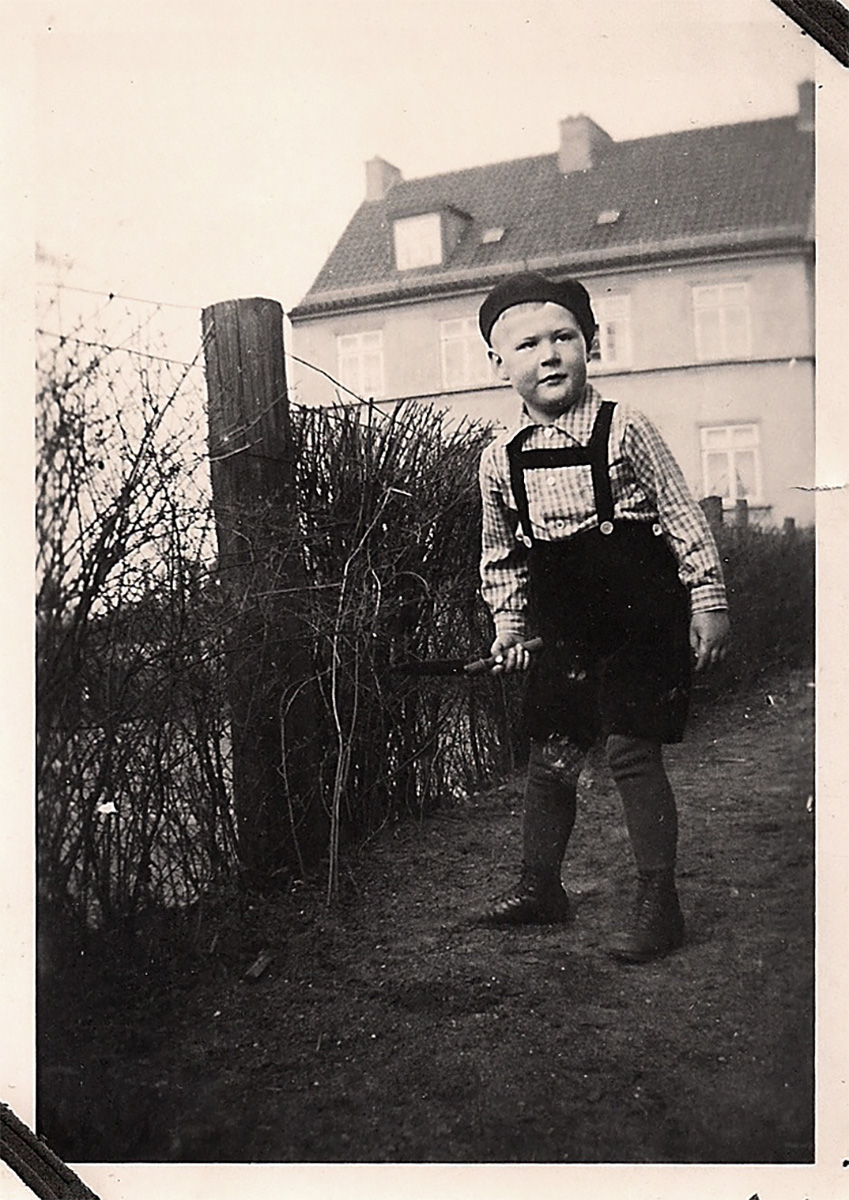

Anita, Helga und Helmut Volkmer, etwa 1937.

Privatbesitz Marlene Volkmer.

Das erste Gehirn, das für die Forschung nach Hamburg gegeben wurde, war das von Helga Volkmer. Sie wurde am 30. November 1941 ermordet und gehörte zu den ersten Opfern der Lüneburger »Kinder-Euthanasie«. Sie ist der Beleg, dass die Lüneburger »Kinderfachabteilung« ihre Arbeit nicht erst 1942 mit den ersten »Reichsausschuss«-Kindern begann, sondern mit Ankunft der Kinder aus den Rotenburger Anstalten der Inneren Mission.

Helga Volkmer ist in der Nazi-Zeit

in der Kinder-Fachabteilung in Lüneburg.

Sie wird am 30. November 1941 ermordet.

Willi Baumert nimmt das Gehirn aus Helgas

totem Körper.

Er untersucht das Gehirn.

Die Ärzte in der Kinder-Fachabteilung Lüneburg machen das bei Helga zum ersten Mal.

Helga Volkmer ist das erste bekannte Opfer

von Hirn-Forschung.

Das ist ein Foto von Helga Volkmer und

ihren Eltern aus dem Jahr 1937.

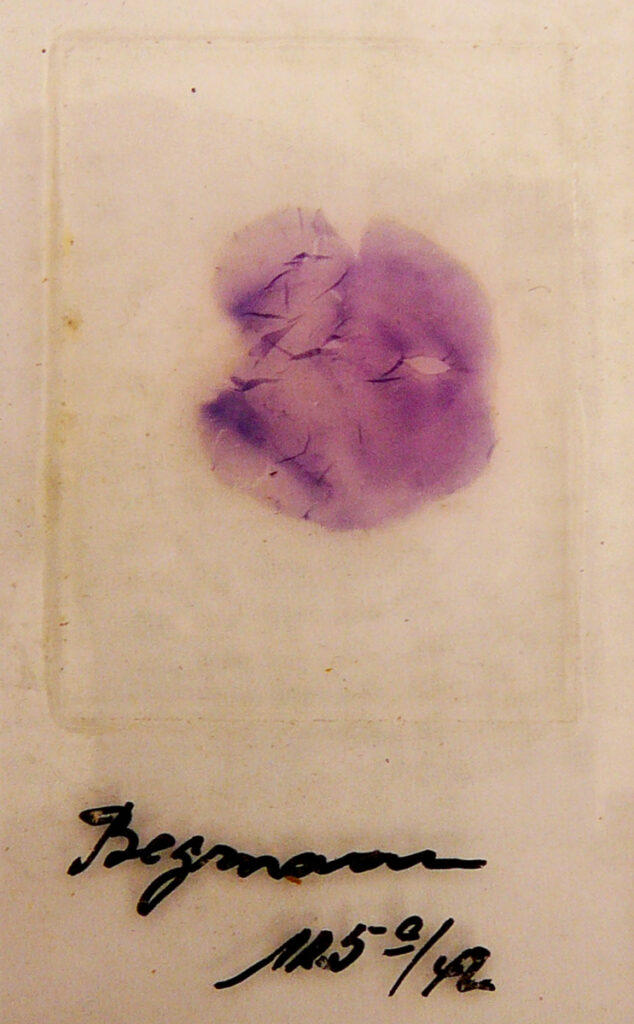

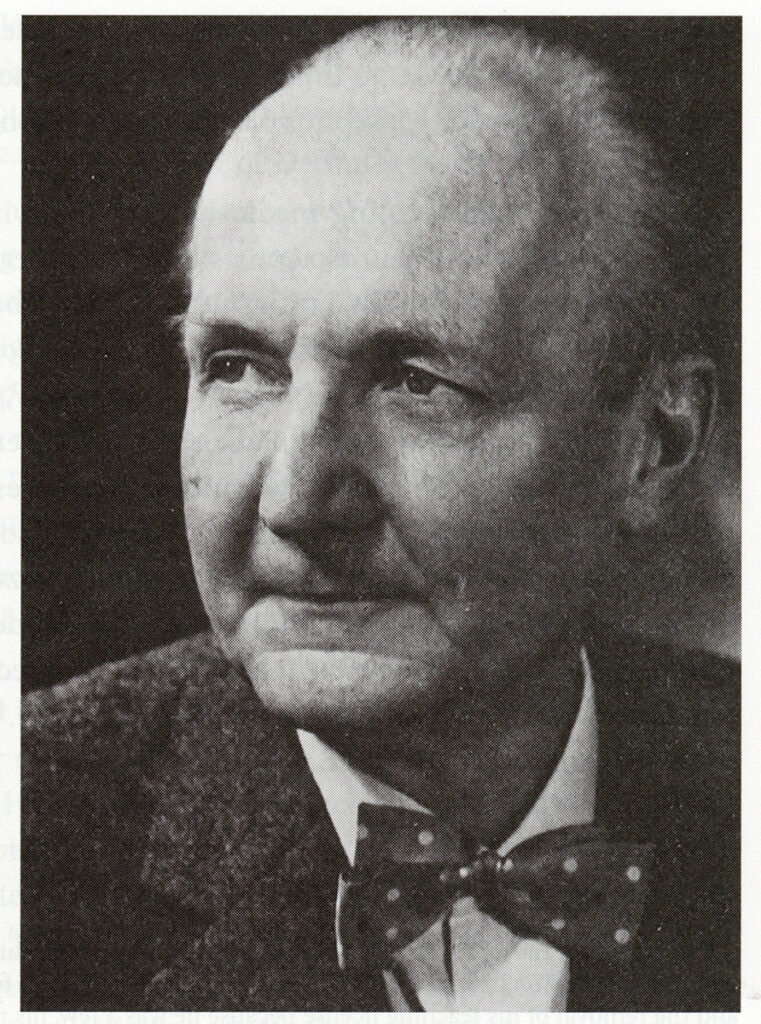

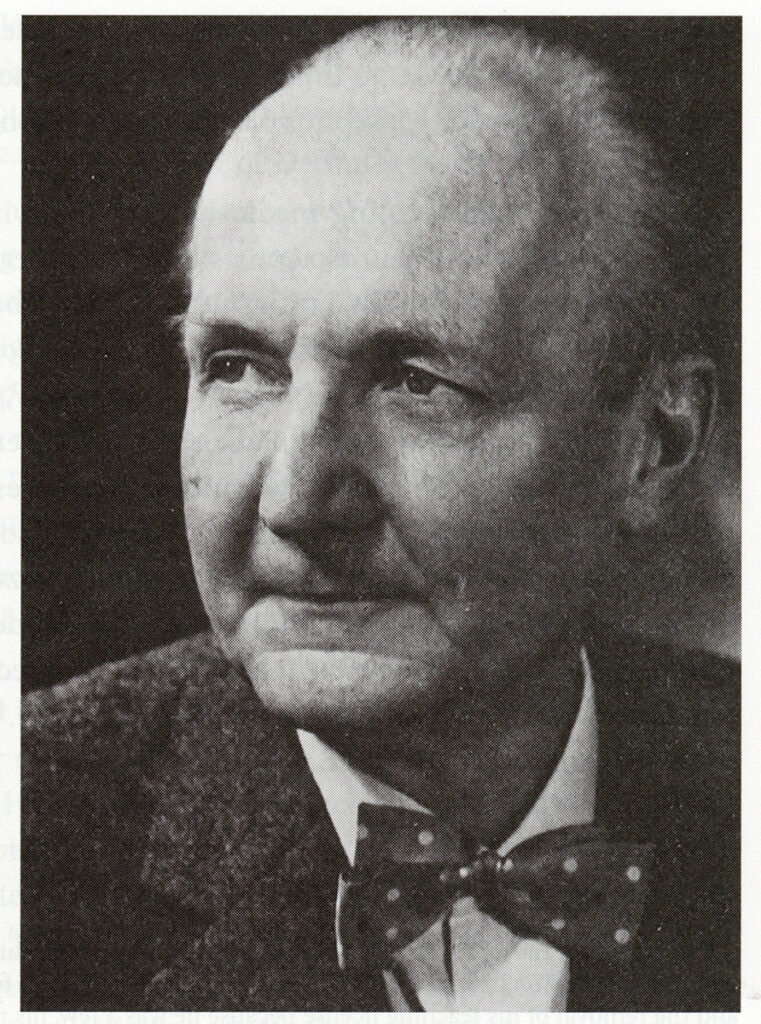

Hans Jacob, nach 1945.

Lawrence Zeidman: Brain Science under the Swastika. Ethical Violations, Resistance, and Victimization of Neuroscientists in Nazi Europe, Oxford 2020.

Am UKE nutzte der Gehirnforscher Hans Jacob die aus Lüneburg kommenden Organe für seine Forschungen. Er arbeitete dem »Reichsausschuss« zu. Eine Zusammenarbeit zwischen »Tötungs-« und Forschungseinrichtungen gab es mit vielen Gehirnforschern. Hans Heinze (Görden) und Julius Hallervorden (Berlin) waren sogar bei Krankenmorden dabei, um gleich nach Todeseintritt mit den Untersuchungen zu beginnen und Sammlungen anzulegen.

Das Krankenhaus in Hamburg gehört

zur Universität.

Die Ärzte im Krankenhaus machen

Hirn-Forschung.

Der Arzt Hans Jacob arbeitet dort und

forscht an Gehirnen.

Die Gehirne kommen aus Lüneburg.

Hans Jacob arbeitet für den Reichsausschuss

von den Nazis.

Darum bekommt er viele Gehirne

und andere Teile von Leichen.

Kinder-Fachabteilungen und Tötungs-Anstalten arbeiten mit den Forschern zusammen.

Die Mörder beliefern die Forscher.

Hans Heinze ist Forscher in Görden.

Julius Hallervorden ist Forscher in Berlin.

Sie sind sogar bei den Kranken-Morden dabei.

Sie untersuchen die Gehirne kurz nach dem Tod.

Die Forscher sammeln die Gehirne.

Das ist ein Foto von Hans Jacob.

Das Foto ist nach dem Jahr 1945 gemacht.

Von hohem wissenschaftlichem Interesse für Willi Baumert waren Kinder, bei denen er das »Hurler-Syndrom« vermutete. Das ist auch der Grund dafür, dass es zu Heinrich Herold aus Duingen besonders viele Gehirnschnitte gab.

Das Hurler-Syndrom ist eine Krankheit.

Der Arzt Willi Baumert forscht

zum Hurler-Syndrom

Er will wissen,

woher die Krankheit kommt.

Er will viel über die Krankheit wissen.

Heinrich Herold kommt aus Duingen.

Er hat die Krankheit Hurler-Syndrom.

Willi Baumert ermordet Heinrich Herold.

Dann nimmt Willi Baumert das Gehirn

aus dem Kopf von Heinrich Herold.

Er schneidet das Gehirn in dünne Scheiben.

So kann er es genau untersuchen.

Das ist ein Foto von Helmut Herold.

Er ist links vor dem Auto.

Neben ihm sind sein Cousin Helmut

und seine Schwester Irmgard.

Das Foto ist aus dem Jahr 1938.

Da ist Heinrich noch zu Hause.

Heinrich Herold, Helmut Sievers und Irmgard Herold (von links nach rechts), vor dem Elternhaus in Duingen, 1938.

Privatbesitz Holger Sievers.

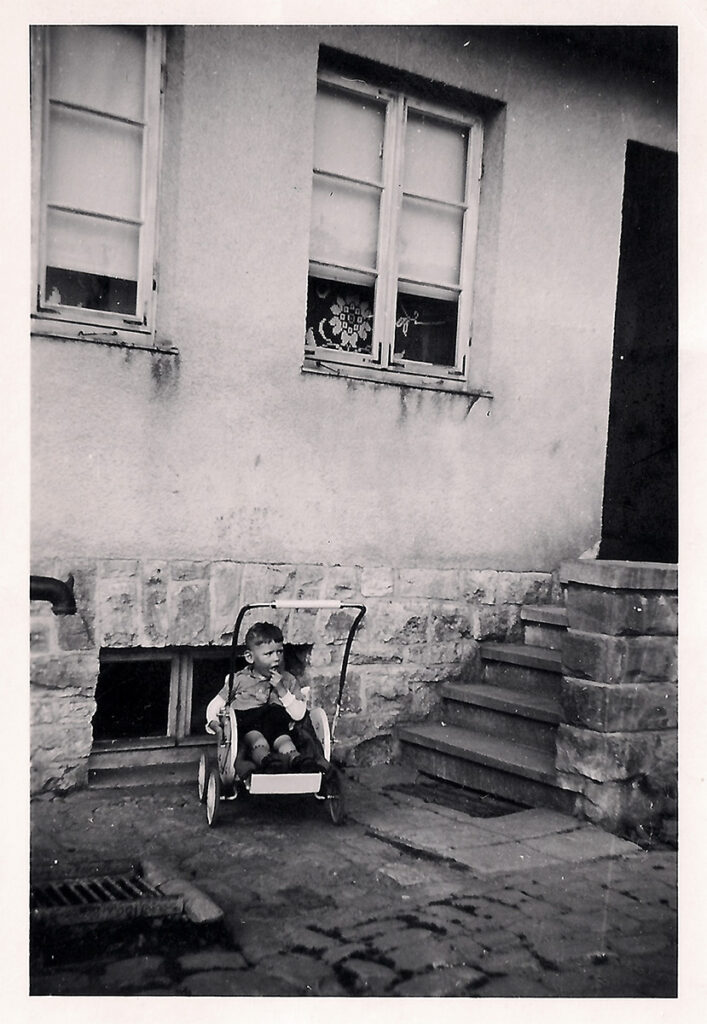

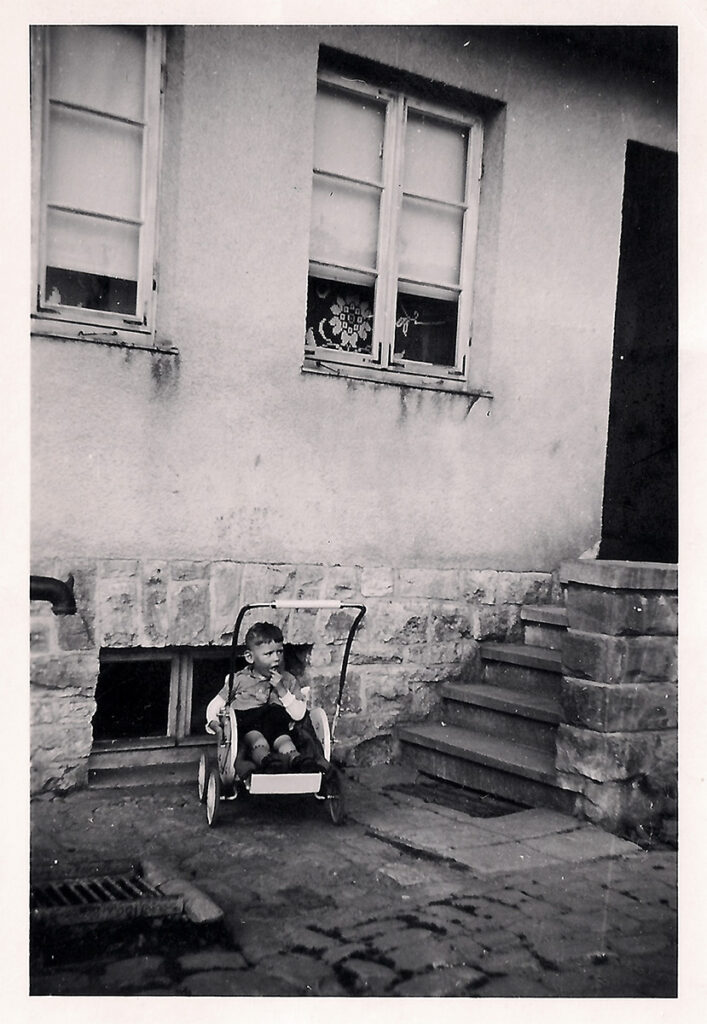

Privatbesitz Familie Schäfer.

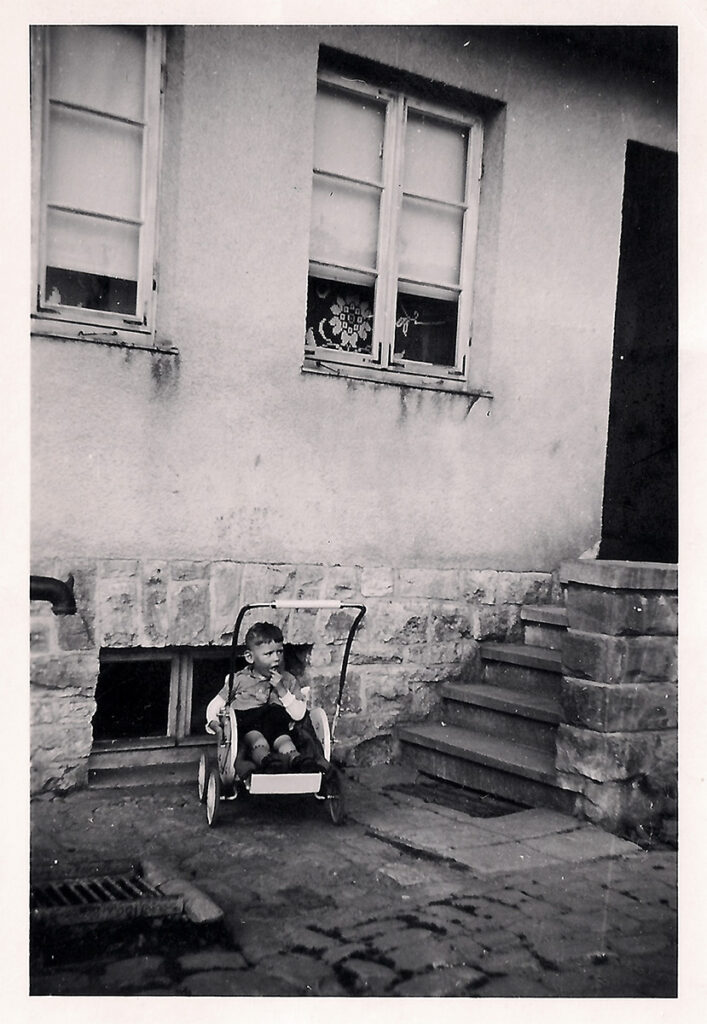

Das ist das letzte Foto von Heinz Schäfer, aufgenommen im Herbst 1941. Wenige Wochen später wurde er in die Lüneburger »Kinderfachabteilung« eingewiesen und war kurz danach bereits tot. Die Eltern konnten es nicht glauben. Der Vater reiste nach Lüneburg und ließ den Sarg öffnen, um sich zu vergewissern. Der Kopf von Heinz‘ Leiche war verbunden. Die Familie konnte sich das nicht erklären, da Heinz offiziell an »Diphtherie u. katarrh. Lungenentzündung« gestorben war.

Das ist ein Foto von Heinz Schäfer

aus dem Jahr 1941.

Es ist das letzte Foto von Heinz.

Kurz danach kommt Heinz

in die Kinder-Fachabteilung nach Lüneburg.

Heinz wird dort ermordet.

Die Eltern können es nicht glauben.

Die Eltern wollen wissen:

Ist Heinz wirklich tot.

Darum reist der Vater nach Lüneburg.

Der Vater will in den Sarg von Heinz gucken.

Man öffnet den Sarg.

Heinz liegt im Sarg.

Er hat einen Verband um den Kopf.

Der Vater fragt:

Warum hat Heinz einen Verband?

Warum hat Heinz eine Verletzung am Kopf?

Die Familie versteht nicht,

warum Heinz einen Verband am Kopf hat

Denn die Familie denkt:

Heinz stirbt an einer Haut-Entzündung.

Da braucht er keinen Verband am Kopf.

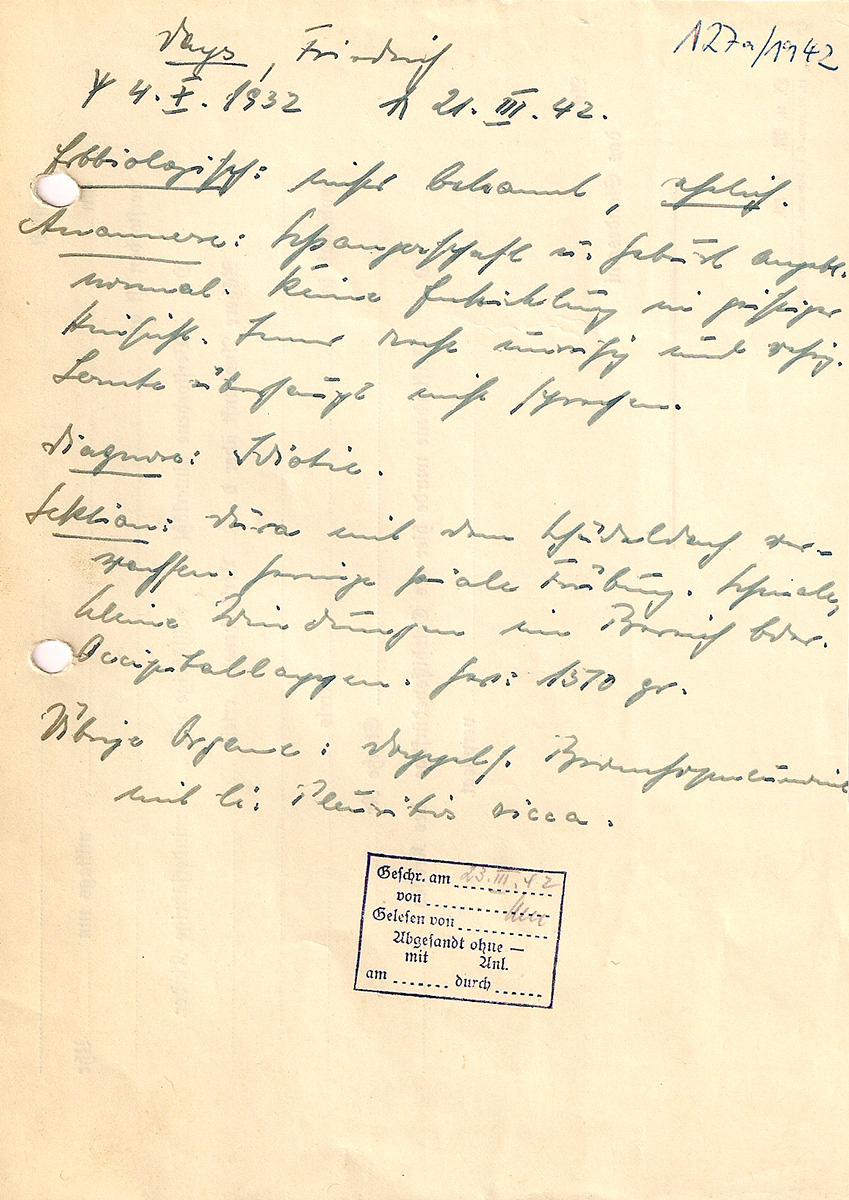

Man verschwieg den Familien, dass die Gehirne entnommen worden waren. Über Heinz Schäfers Tod wurde in der Familie immer wieder gerätselt. 2012 konnten ihm im UKE eingelagerte Gehirn-Präparate zugeordnet werden. Die Familie wurde erstmals über sein wahres Schicksal aufgeklärt. Nach vielen Jahrzehnten erhielt sie Antwort auf die Frage, warum Heinz‘ Kopf verbunden gewesen war. Willi Baumert und Hans Jacob hatten sein Gehirn für ihre Forschungen benutzt.

Die Ärzte sagen der Familie nicht,

dass sie Heinz das Gehirn rausgeschnitten haben.

Die Familie weiß lange nicht Bescheid.

Erst im Jahr 2012 findet man Teile von Gehirnen

im Krankenhaus in Hamburg

Einige von den Teilen gehören zu Heinz.

Die Familie weiß jetzt die Wahrheit.

Die Familie weiß:

Heinz wird in der Nazi-Zeit ermordet.

Die Ärzte schneiden ihm das Gehirn raus.

Darum hat Heinz den Verband am Kopf.

Die Ärzte Hans Jacob und Willi Baumert haben alles aufgeschrieben über das Gehirn von Heinz.

Das sind die Mitschriften aus dem Jahr 1942.

Mitschrift von Willi Baumert über die Untersuchung des Gehirns von Heinz Schäfer, 1942.

Erste Seite der Mitschrift von Hans Jacob über die Untersuchung des Gehirns von Heinz Schäfer, Universitätsklinikum Hamburg-Eppendorf, 1942.

Institut für Geschichte und Ethik der Medizin Hamburg.

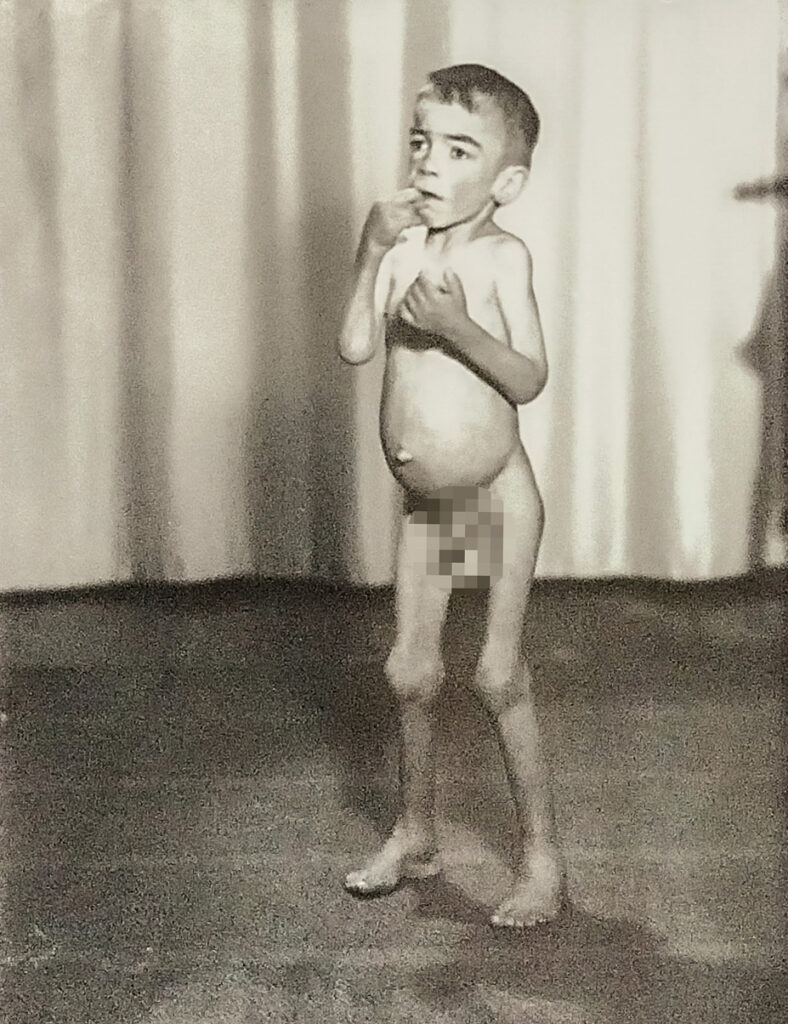

In diesen Auszügen befinden sich schockierende Bilder. Sie zu zeigen, ist umstrittenIn diesen Auszügen befinden sich schockierende Bilder. Sie zu zeigen, ist umstritten.

Entscheiden Sie für sich, ob Sie den Auszug öffnen.

In dieser Schublade sind schlimme Fotos.

Die Fotos sind sehr grausam.

Einige Leute sagen: Es ist gut, die Bilder zu zeigen.

Einige Leute sagen:

Es ist schlecht, die Bilder zu zeigen.

Sie müssen selbst entscheiden,

ob Sie die Fotos ansehen oder nicht.

Wanne zur Leichenöffnung, etwa 1941.

ArEGL.

Im Oktober 2023 wurde im Keller von Haus 25, dem Standort der ehemaligen »Kinderfachabteilung«, diese Wanne gefunden. Mit hoher Wahrscheinlichkeit handelt es sich um eine Sektionswanne. Spuren in den Kellerräumen von Haus 25 deuten darauf hin, dass die Leichen der Kinder und Jugendlichen nicht über das Anstaltsgelände in den damaligen offiziellen Raum für Leichenöffnungen gebracht, sondern vor Ort in Haus 25 geöffnet wurden.

Das ist ein Foto von einer Wanne.

Man findet diese Wanne im Oktober 2023

in der Anstalt in Lüneburg.

Die Wanne war im Keller von Haus 25.

Hier war in der Nazi-Zeit

die Kinder-Fachabteilung.

Darum glauben wir:

Diese Wanne war für Leichen.

In dieser Wanne hat man die Leichen aufgeschnitten.

Wir vermuten:

Im Keller von Haus 25 hat man Leichen aufgeschnitten.

Man hat hier die Leichen von den Kindern

aus Haus 25 aufgeschnitten.

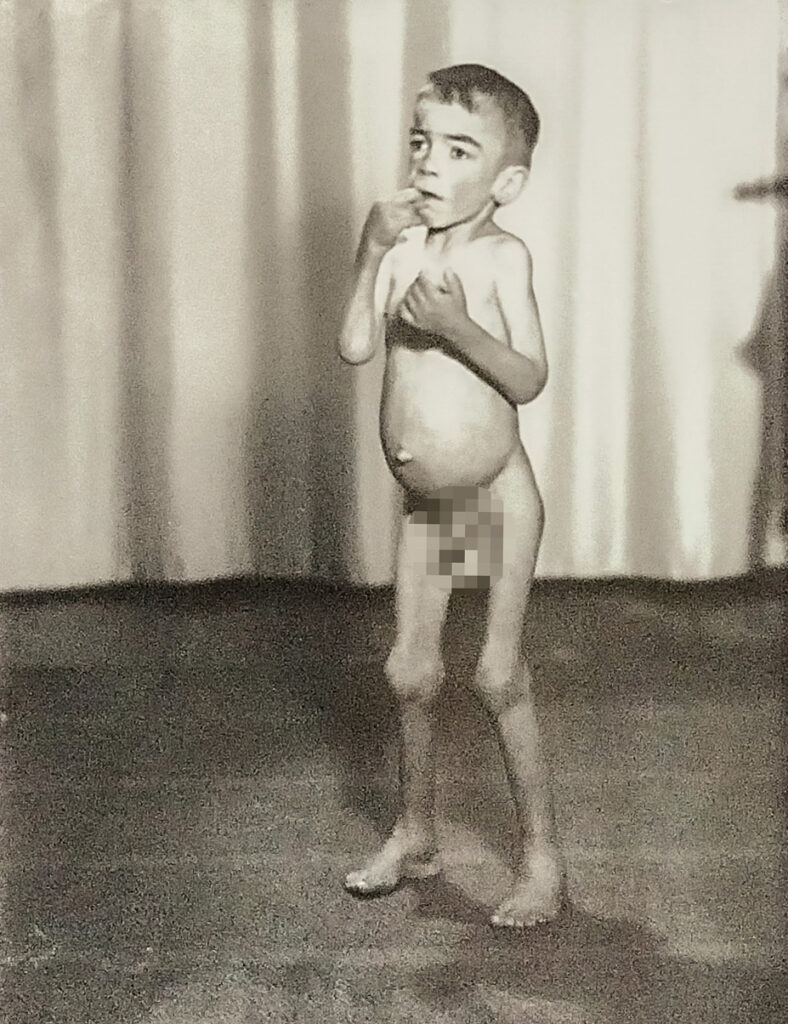

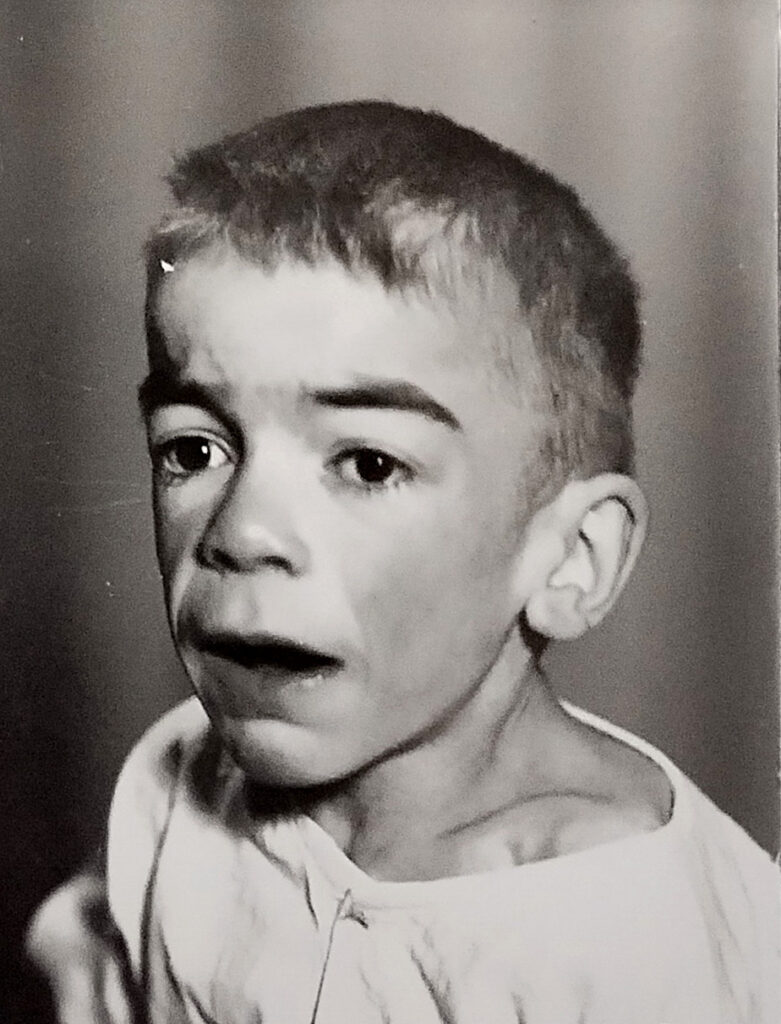

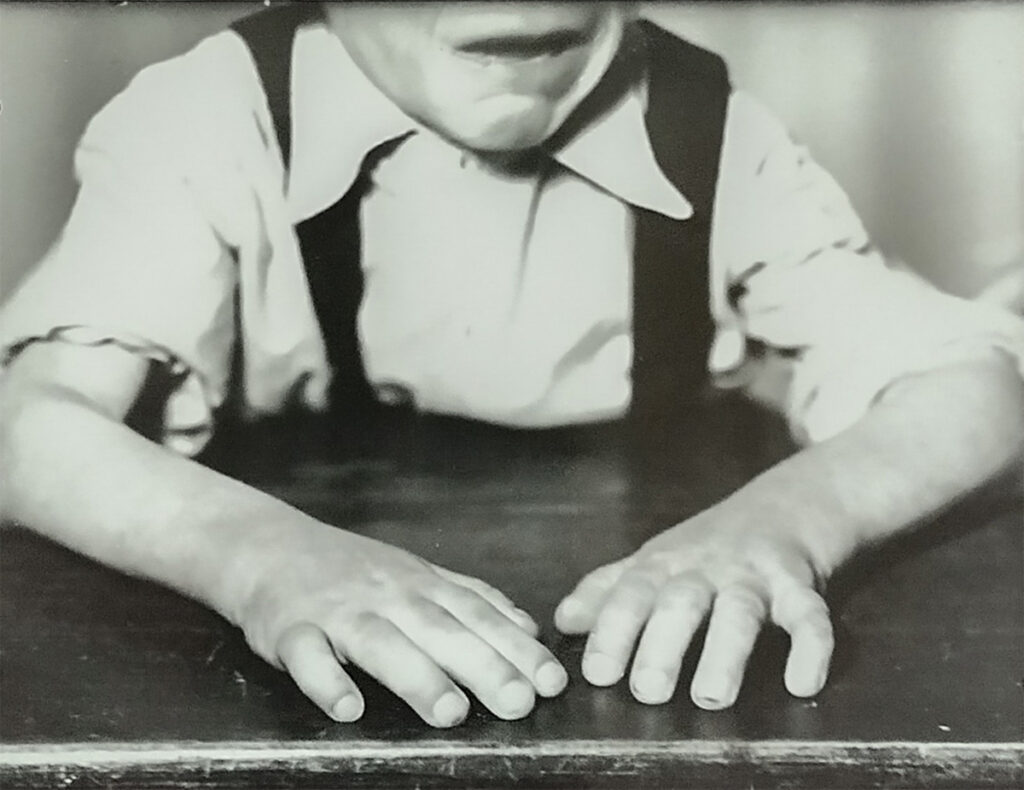

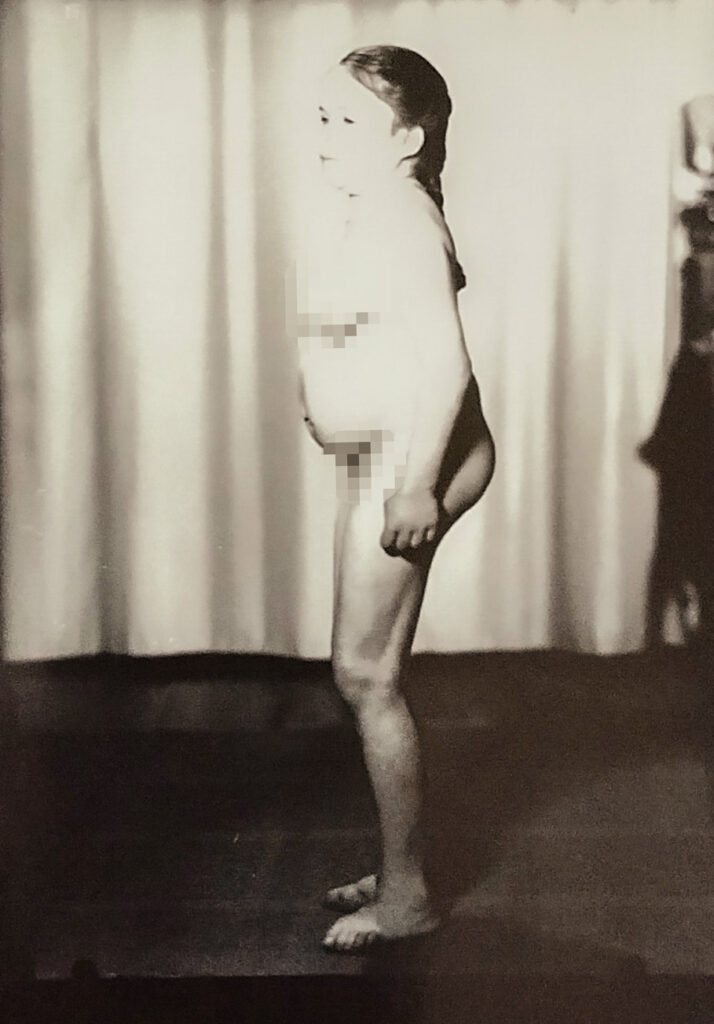

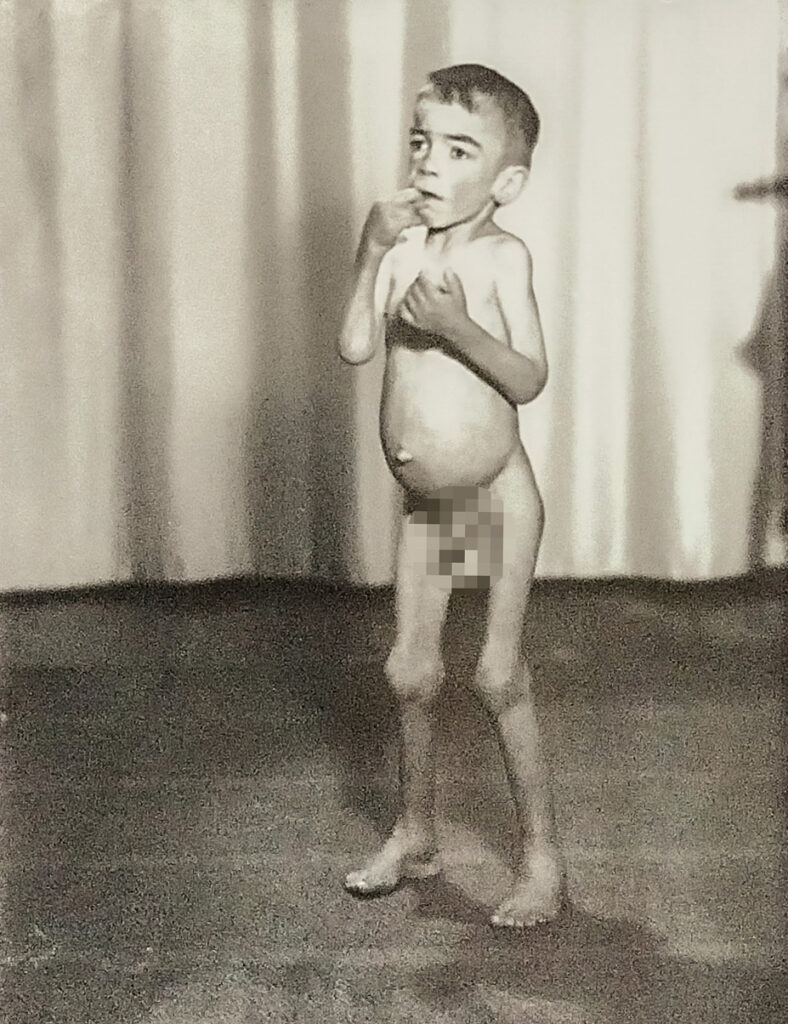

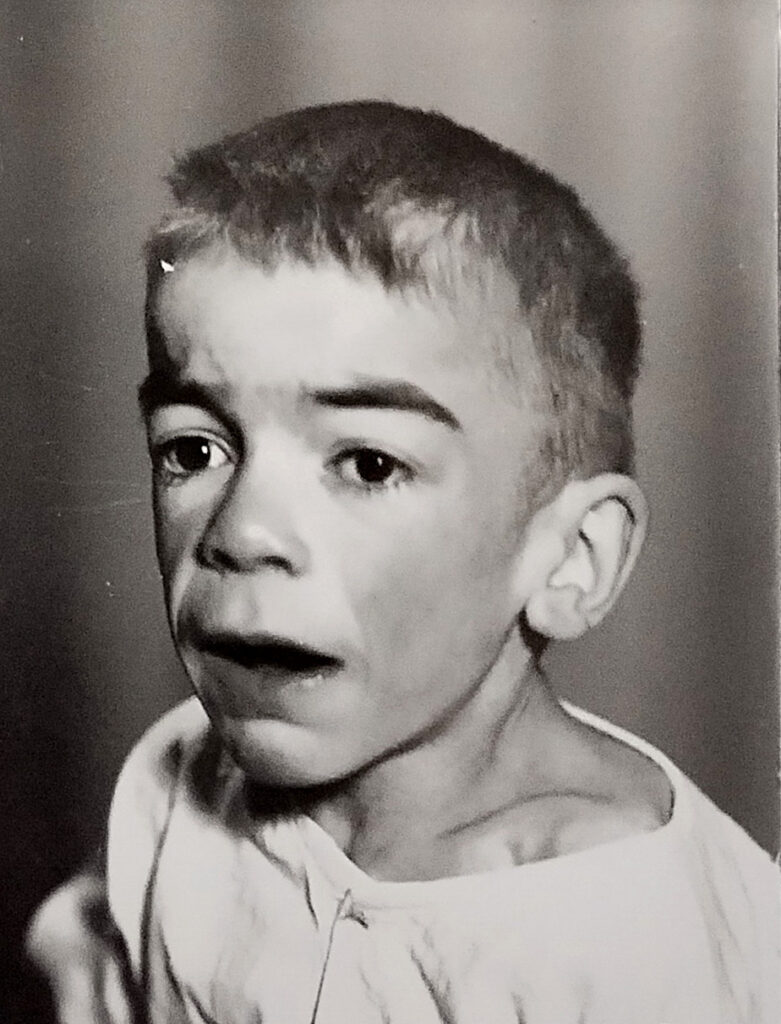

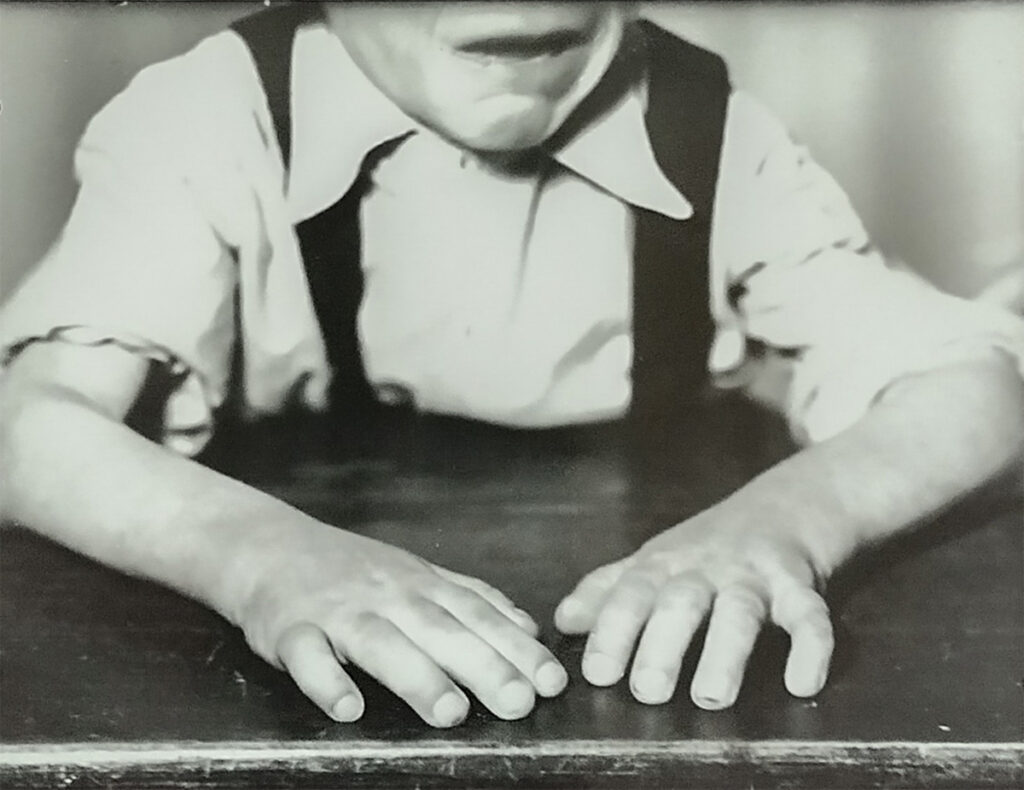

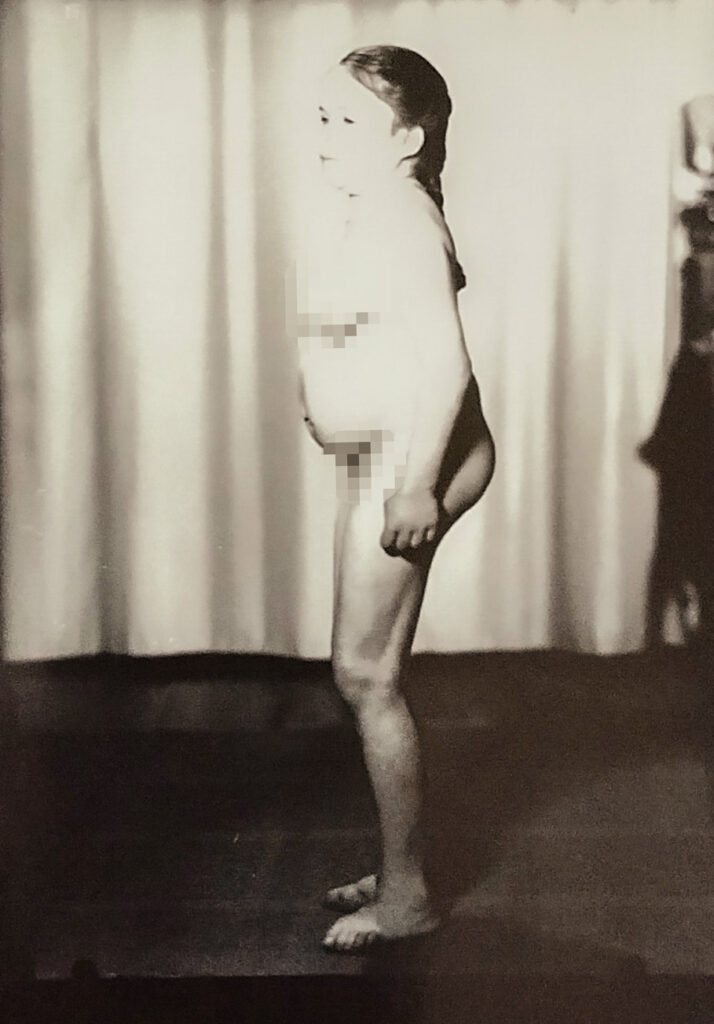

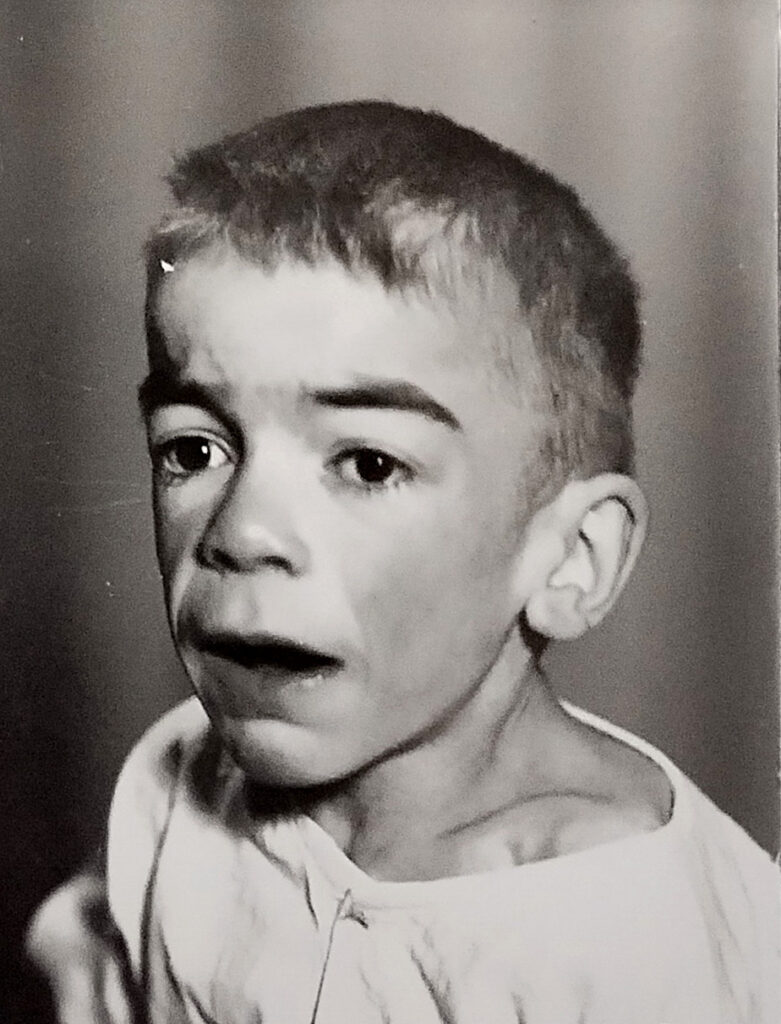

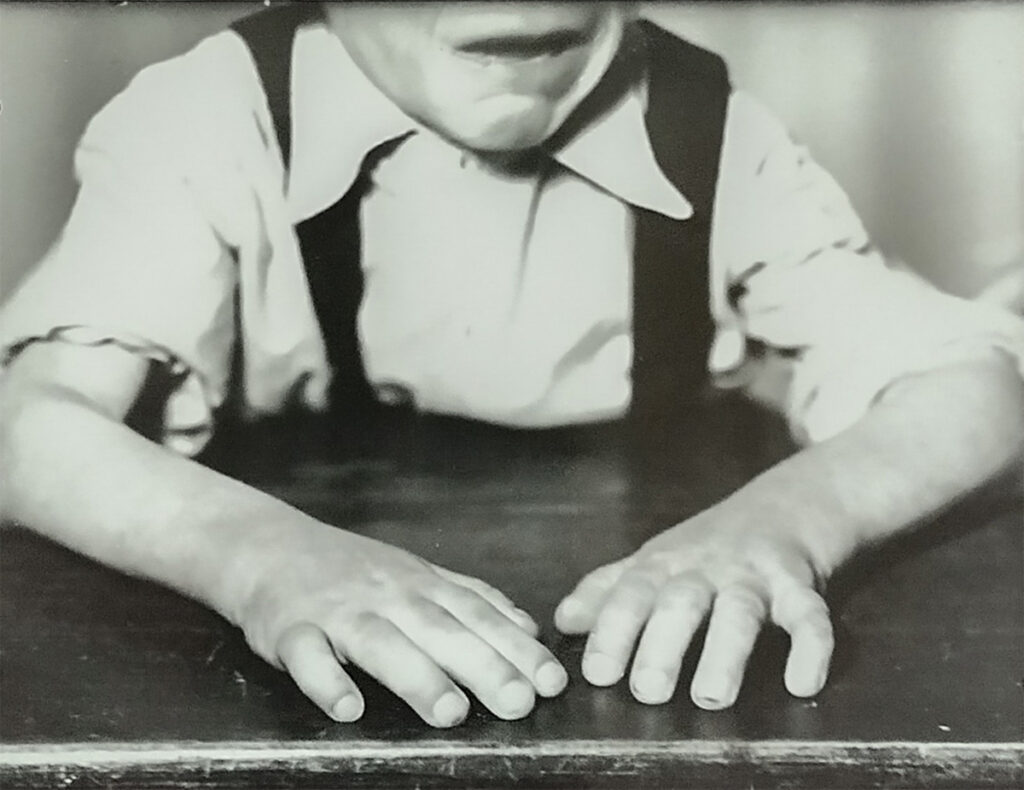

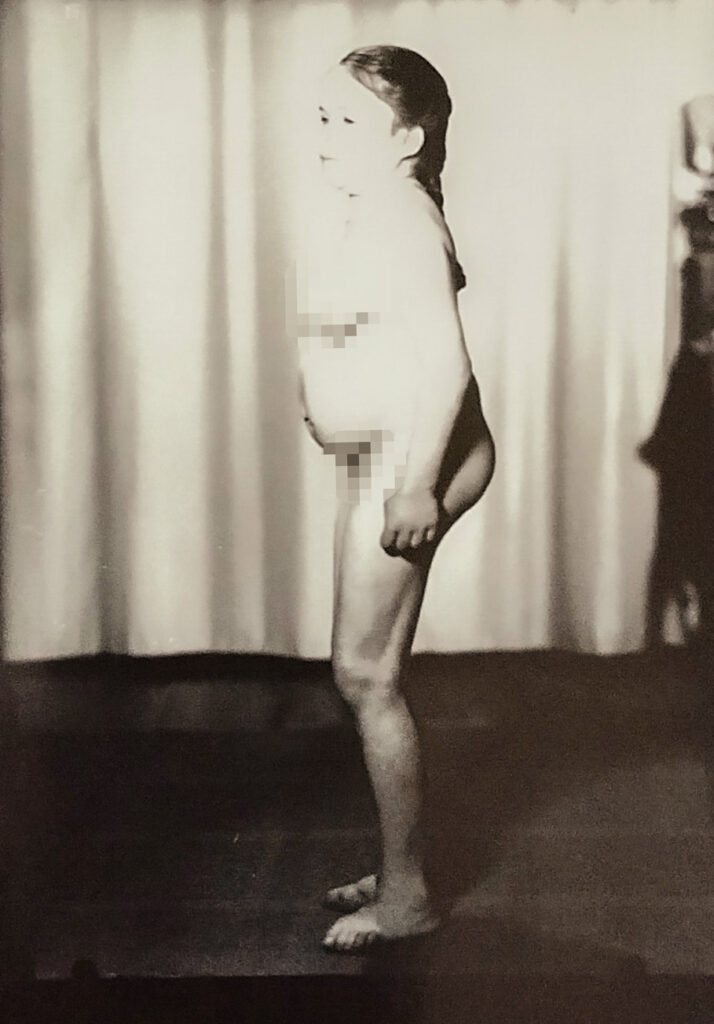

Das sind problematische Bilder. Sie zeigen einen Jungen und ein Mädchen in großer Not und elendem Zustand. Es ist nicht bekannt, wer die beiden Kinder sind. Die Fotos nutzte Willi Baumert für seine »Forschung«. Es sind entwürdigende, grauenhafte Aufnahmen. Sie zeigen schonungslos die Brutalität und Unmenschlichkeit, die die Kinder in der Lüneburger »Kinderfachabteilung« erleben mussten. Nur deshalb zeigen wir sie.

Das sind Fotos von Kindern

in der Kinder-Fachabteilung in Lüneburg.

Die Fotos sind aus den Jahr 1942 und 1943.

Die Fotos sind sehr grausam.

Die Fotos zeigen:

• Die Kinder werden schlecht behandelt.

• Die Kinder haben keine Rechte.

• Die Kinder sind in großer Not.

• Die Kinder müssen leiden.

Die Menschen sollen wissen,

wie es in der Nazi-Zeit war.

Darum zeigen wir diese Fotos.

Wir wissen heute nicht:

Wer sind die Kinder.

Wir wissen nur:

Der Arzt Willi Baumert hat mit den Fotos geforscht.

Die Fotografin Ruth Supper hat die Fotos gemacht.

Fünf Aufnahmen von Kindern, aufgenommen in der »Kinderfachabteilung« Lüneburg, 1942/1943. Fotografin Ruth Supper.

ArEGL FB 2/34.

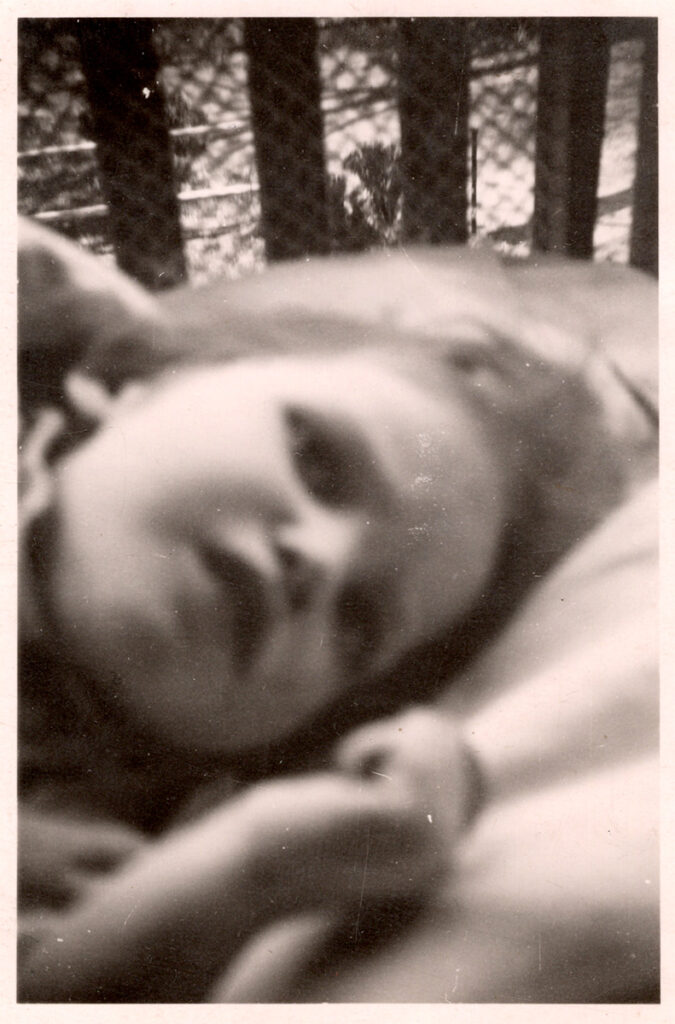

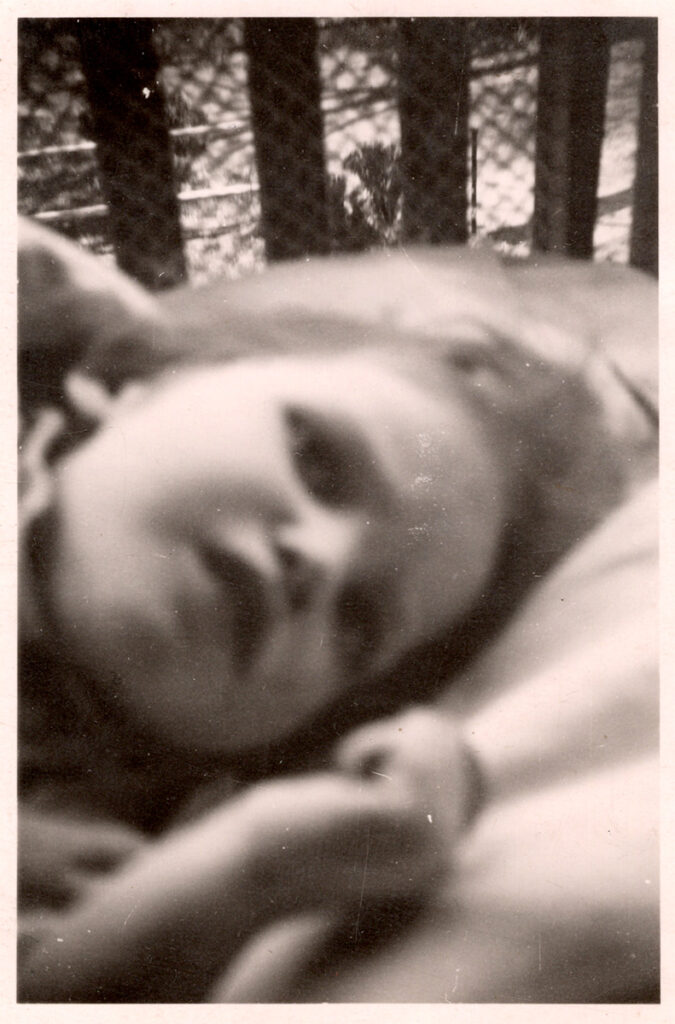

Inge Roxin, »Kinderfachabteilung« Lüneburg 1943.

Privatbesitz Sigrid Roxin.

Die Kinder wurden mit Krankheitserregern krank gemacht, um die Wirksamkeit des nicht zugelassenen Medikamentes »Eubasin« zu erforschen. Mariechen Petersen war nur während der Zeit, in der ihre Mutter sie besuchen konnte, nicht krank. Bei ihrer Nachbarin Inge Roxin wirkte »Eubasin«. Sie wurde gesund, bevor Willi Baumert sie ermordete.

Dieses Foto wurde in der »Kinderfachabteilung« aufgenommen. Das Bild zeigt, dass es Inge Roxin schlecht ging. An ihr wurden Menschenversuche durchgeführt. Das Bild ist problematisch. Aber es nicht zu zeigen, verharmlost das tatsächliche Elend. Von Mariechen Petersen gibt es kein Foto.

Es geht den Kindern in der Kinder-Fachabteilung

sehr schlecht.

Die Kinder werden schwer krank.

Die Ärzte machen die Kinder mit Absicht krank.

Dann probieren die Ärzte neue Medikamente

an den Kindern aus.

Diese Medikamente sind noch nicht erlaubt.

Die Ärzte machen Menschen-Versuche.

Sie machen auch Versuche

mit Mariechen Petersen und Inge Roxin.

Das ist ein Foto von Inge Roxin aus dem Jahr 1943.

Sie ist in der Kinder-Fachabteilung in Lüneburg.

Die Ärzte machen Versuche mit ihr:

Sie bekommt ein verbotenes Medikament.

Das Foto zeigt:

Inge Roxin geht es sehr schlecht.

Dann bekommt sie das Medikament.

Sie überlebt und es geht ihr besser.

Aber dann wird sie von Willi Baumert ermordet.

Das Foto von Inge Roxin ist nicht schön.

Aber wir zeigen es trotzdem.

Jeder soll sehen, wie schlimm es damals war.

Es ist ungewiss, ob es in der Lüneburger »Kinderfachabteilung« auch Versuche mit Impfstoffen gegen Tuberkulose, Scharlach oder andere Erkrankungen gegeben hat. Im Gegensatz zur Behandlung erwachsener Erkrankter, insbesondere in der sogenannten »Ausländersammelstelle«, gibt es für Kinder und Jugendliche bisher keinen Beleg dafür.

Es gibt viele Menschen-Versuche in der Anstalt

in Lüneburg in der Nazi-Zeit.

Vielleicht testet man Impfstoffe gegen Scharlach

oder Tuberkulose in der Kinder-Fach-Abteilung.

Das ist aber nicht sicher.

Es gibt keine Beweise dafür.

An der Forschung in der »Kinderfachabteilung« waren viele Beschäftigte aus der Pflege, aber auch aus der Verwaltung und nichtpflegerischen Bereichen der Lüneburger Heil- und Pflegeanstalt beteiligt. Sie alle unternahmen nichts, um das Kindersterben zu verhindern oder die Situation der Kinder zu verbessern. Sie können daher als Helferinnen und Helfer angesehen werden.

Viele machen mit bei der Forschung

in der Kinder-Fachabteilung.

Es sind nicht nur Pfleger.

Es sind auch

• Menschen aus dem Büro.

• Fahrer.

• Putzfrauen.

Sie alle helfen den Ärzten und gucken zu.

Sie tun nichts.

Sie helfen den Kindern nicht.

Sie helfen den Mördern.

Im Raum ENTSCHEIDEN gibt es mehr Infos

zu dem Thema.

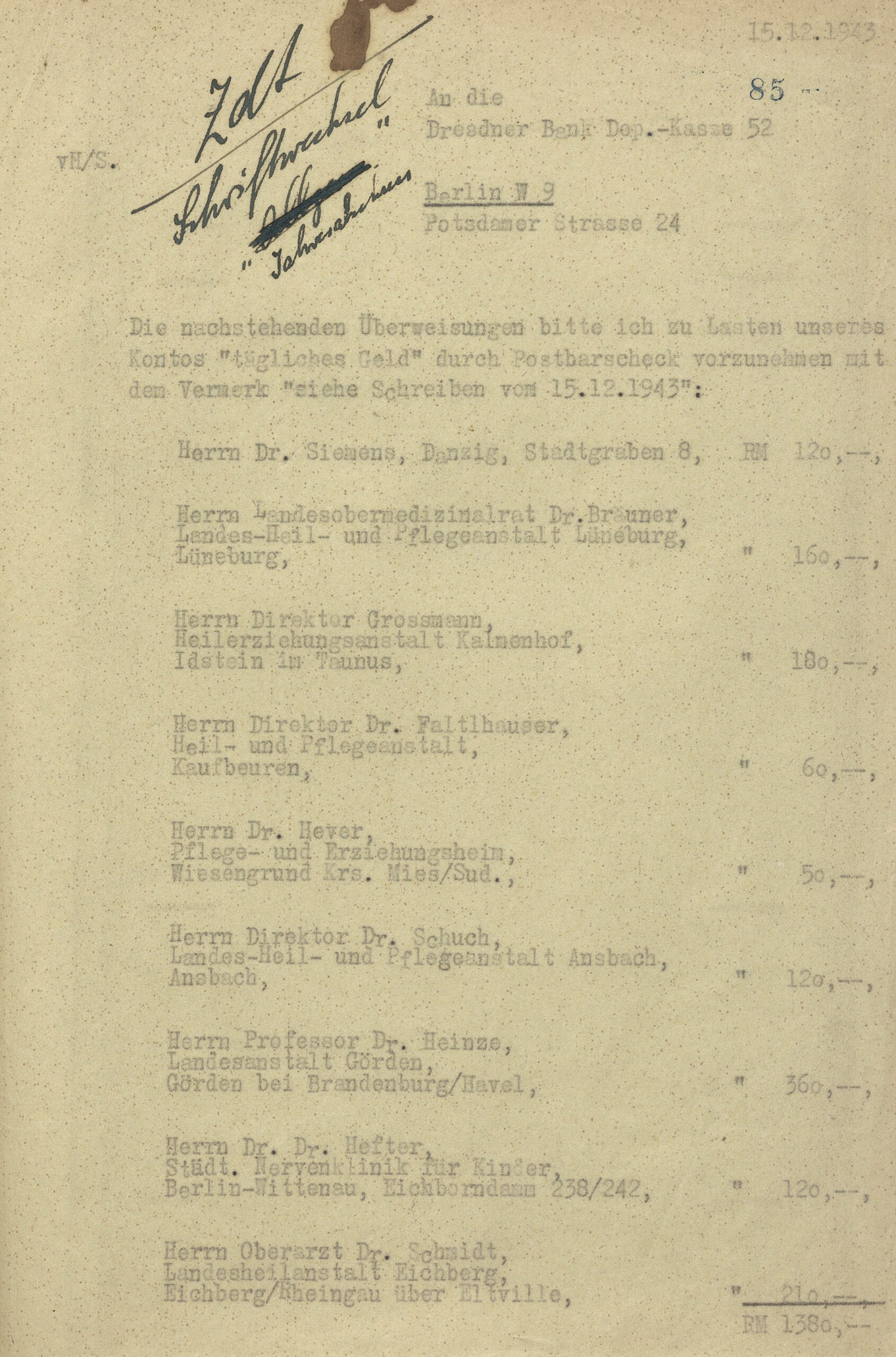

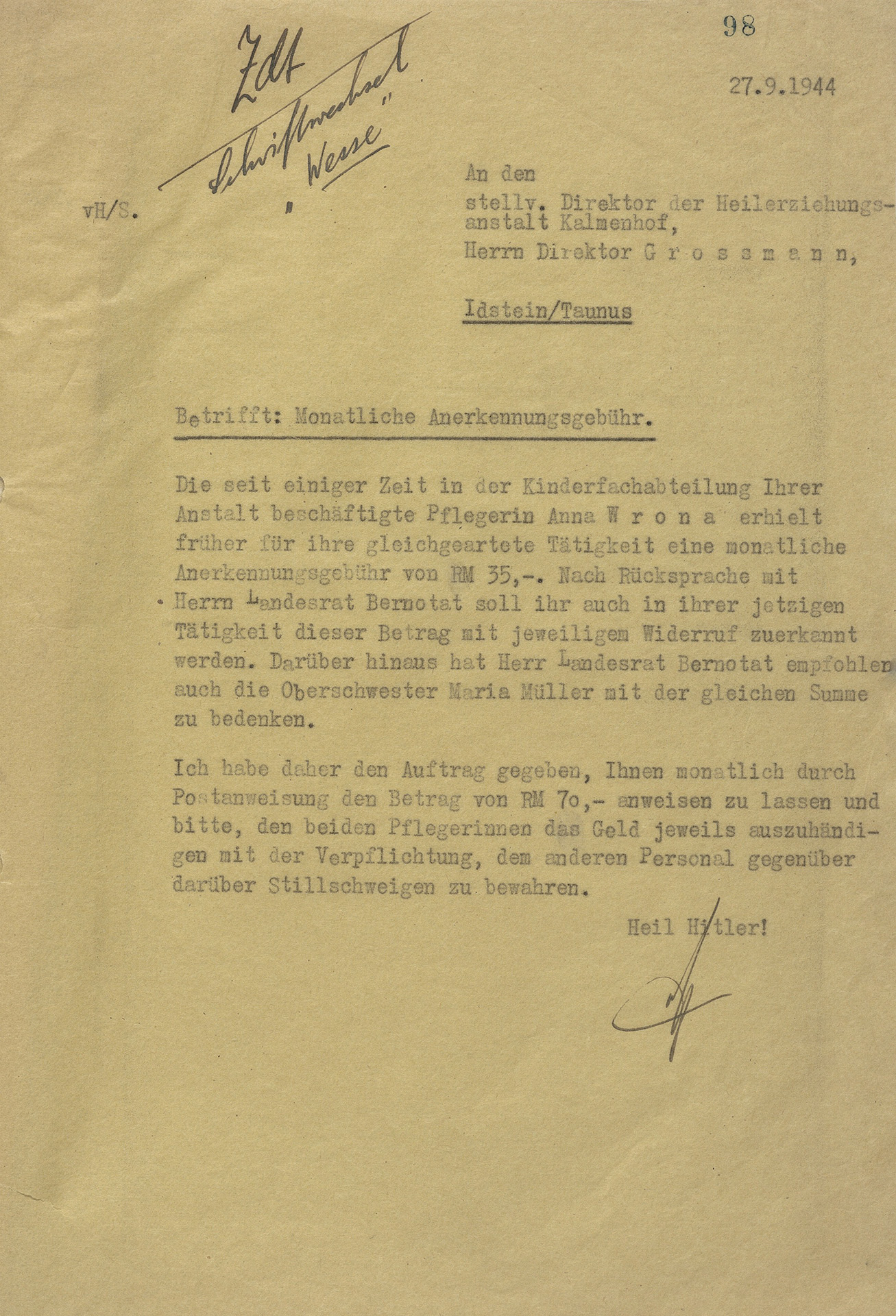

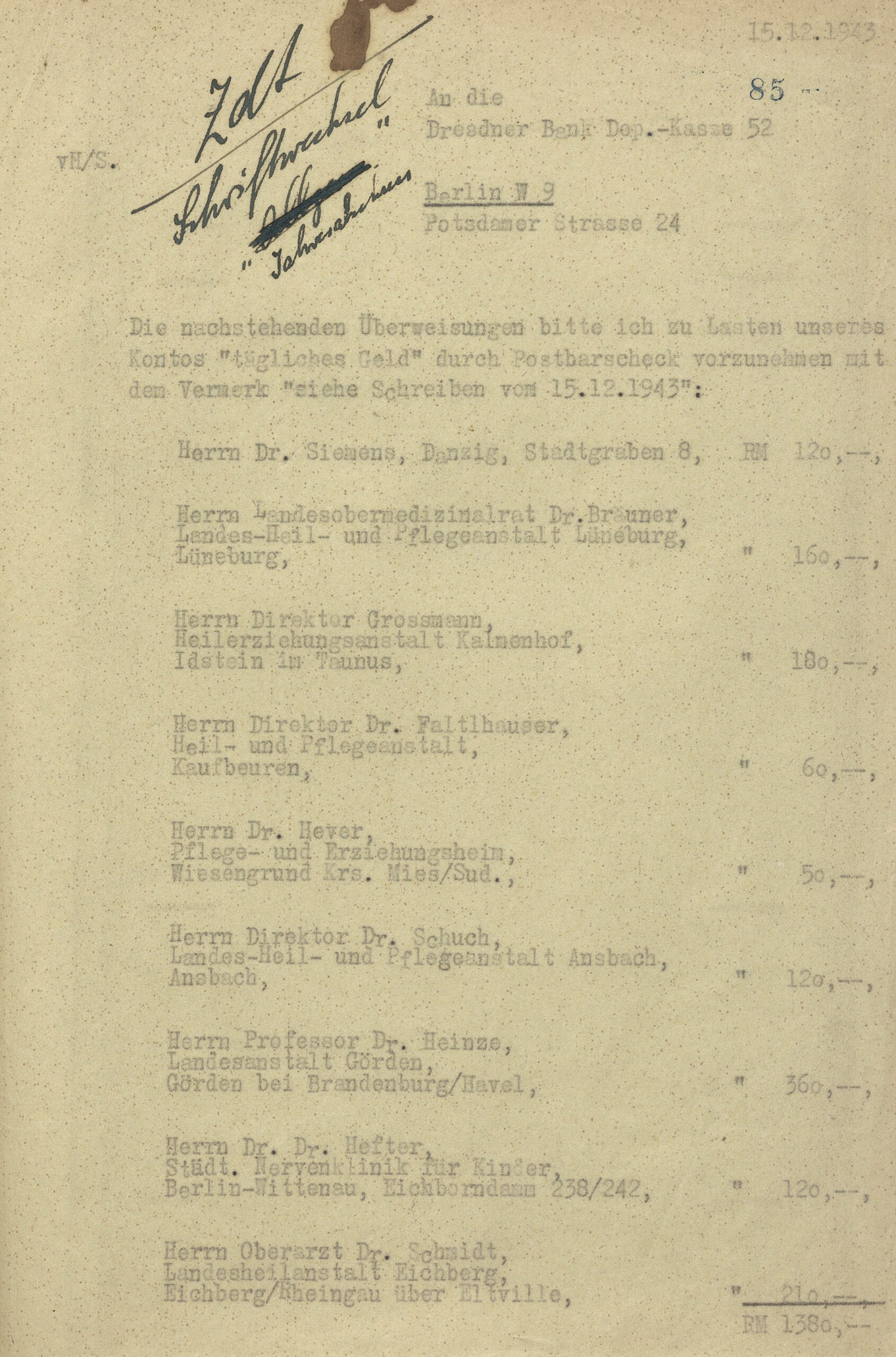

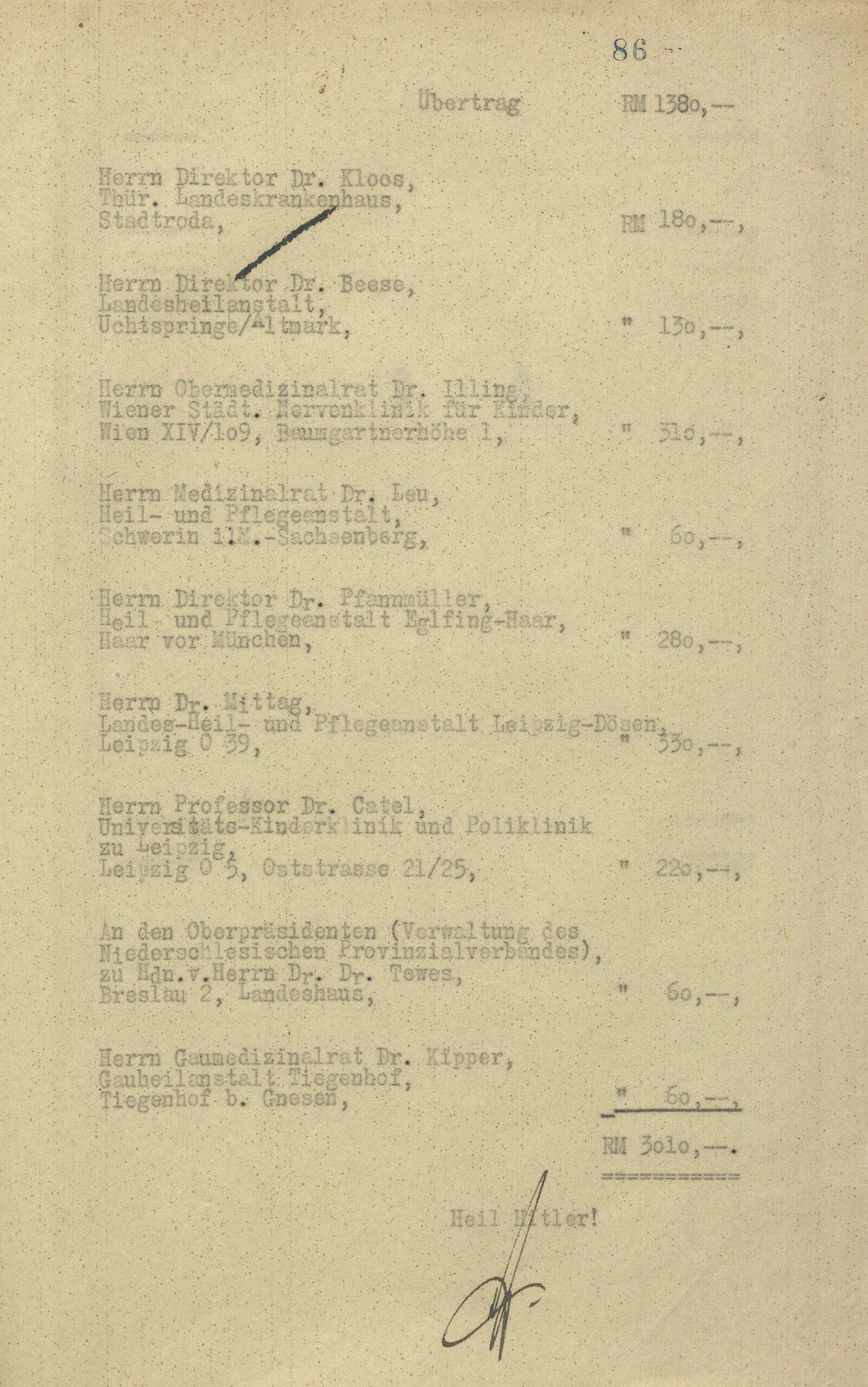

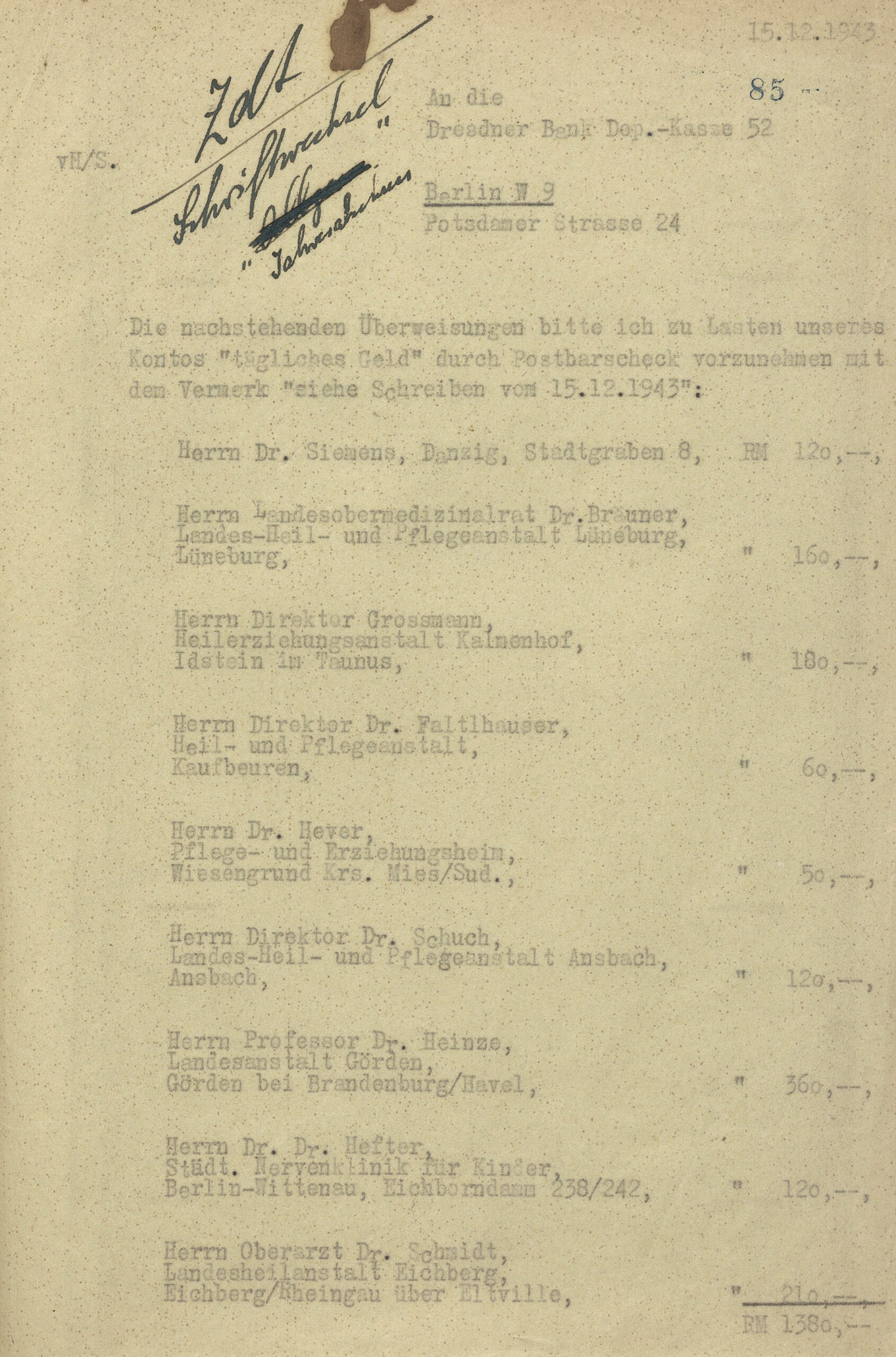

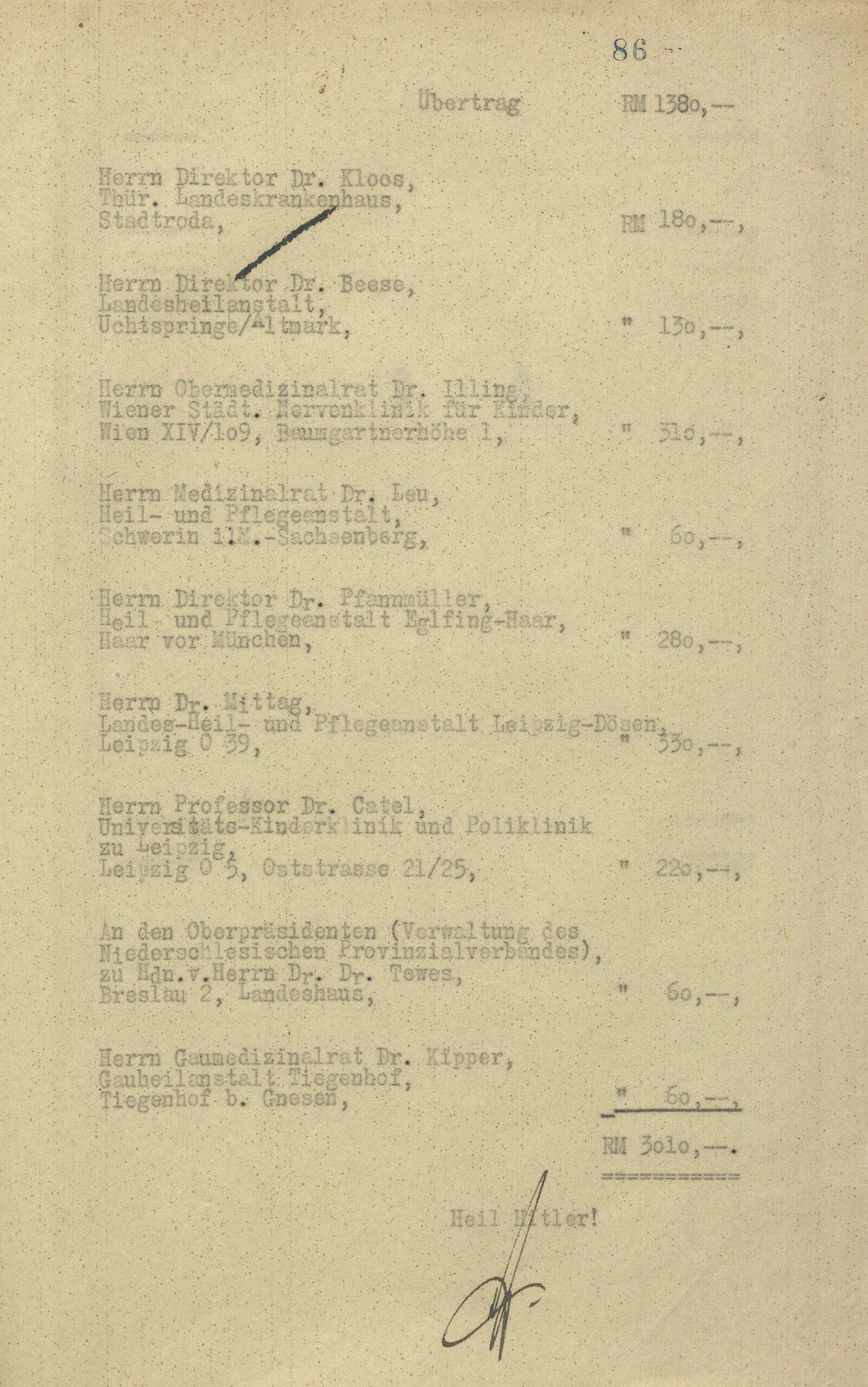

Brief an die Dresdner Bank mit der Anweisung über die Auszahlung von »Sonderzuwendungen« vom 15.12.1943.

BArch NS 51/227.

Für das Morden in der »Kinderfachabteilung« erhielten die Beteiligten und Mithelferinnen »Sonderzuwendungen« als Belohnung. Auf dieser Liste ist erkennbar, dass die »Kinderfachabteilung« Görden den höchsten Betrag für »Sonderzuwendungen« erhielt, weil es dort 1943 besonders viele Beteiligte und Mithelferinnen an der »Kinder-Euthanasie« gab. Die Liste führt nicht alle »Kinderfachabteilungen« auf, in denen in diesem Jahr Kinder und Jugendliche ermordet wurden.

In der Nazi-Zeit gibt es extra Geld

für den Kinder-Mord

Alle Mitarbeiter bekommen extra Geld,

wenn sie beim Kinder-Mord mitmachen.

Das extra Geld gibt es immer zu Weihnachten.

Das ist eine Liste aus dem Jahr 1943

mit Kinder-Fachabteilungen.

Die Liste zeigt:

Wieviel extra Geld bekommt die Kinder-Fachabteilung von einer Anstalt.

Die Kinder-Fachabteilung in Görden steht ganz oben auf der Liste.

Dort haben sehr viele Menschen

beim Kinder-Mord mitgemacht.

Das ist ein Brief an die Dresdner Bank.

Die Bank soll das extra Geld an die Anstalten auszahlen.

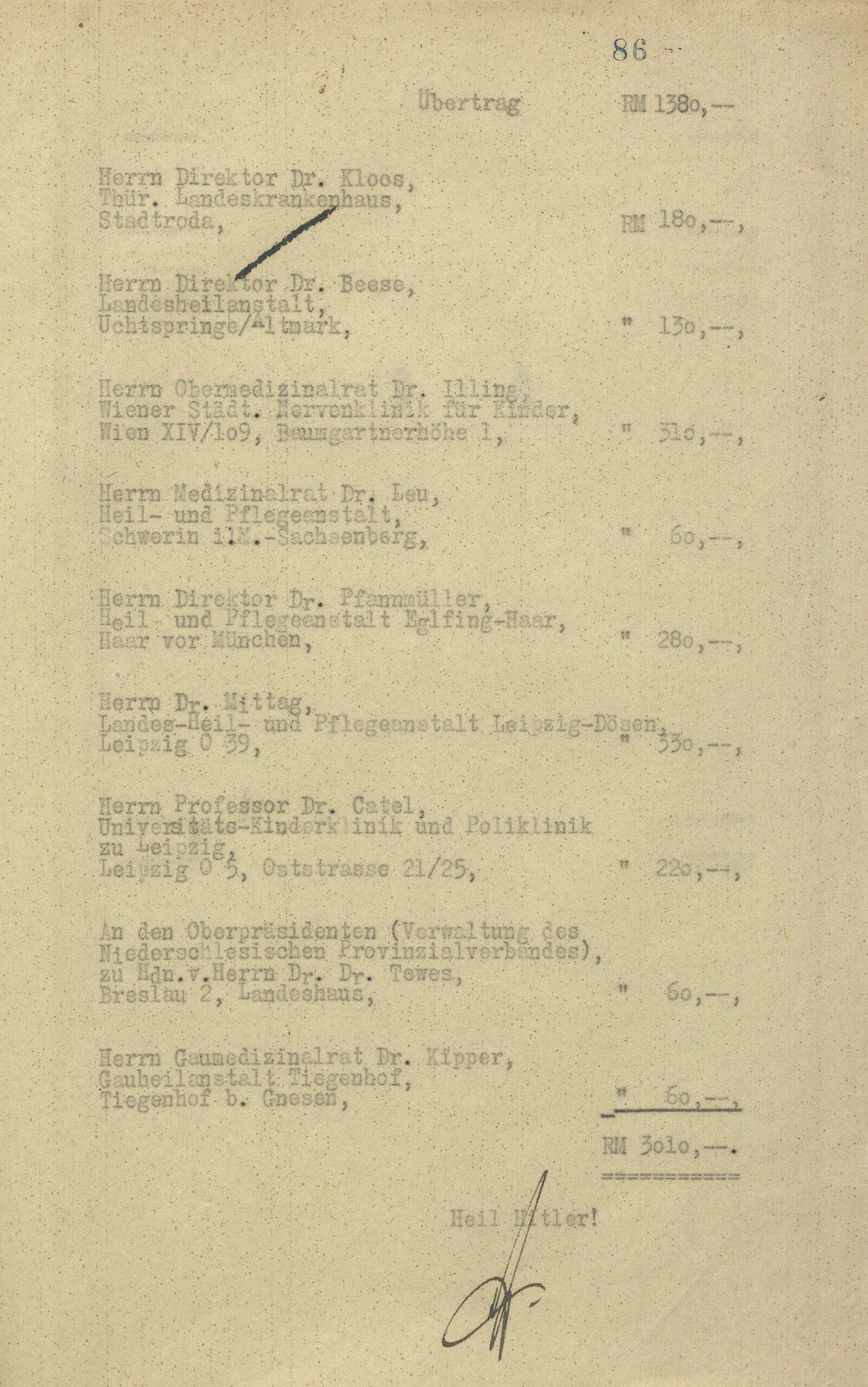

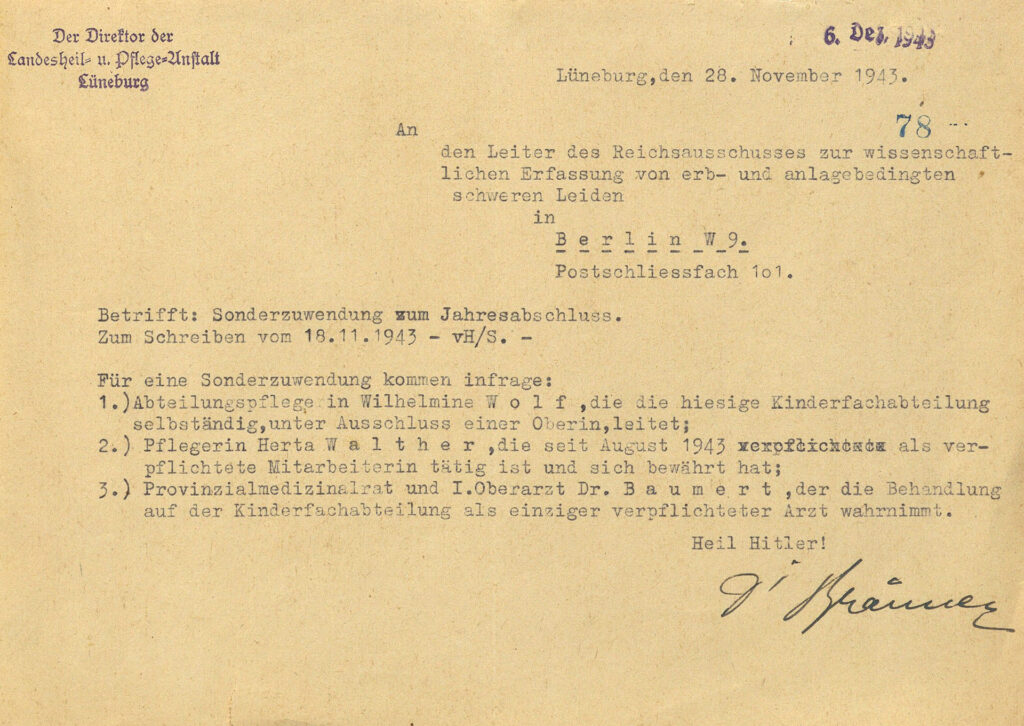

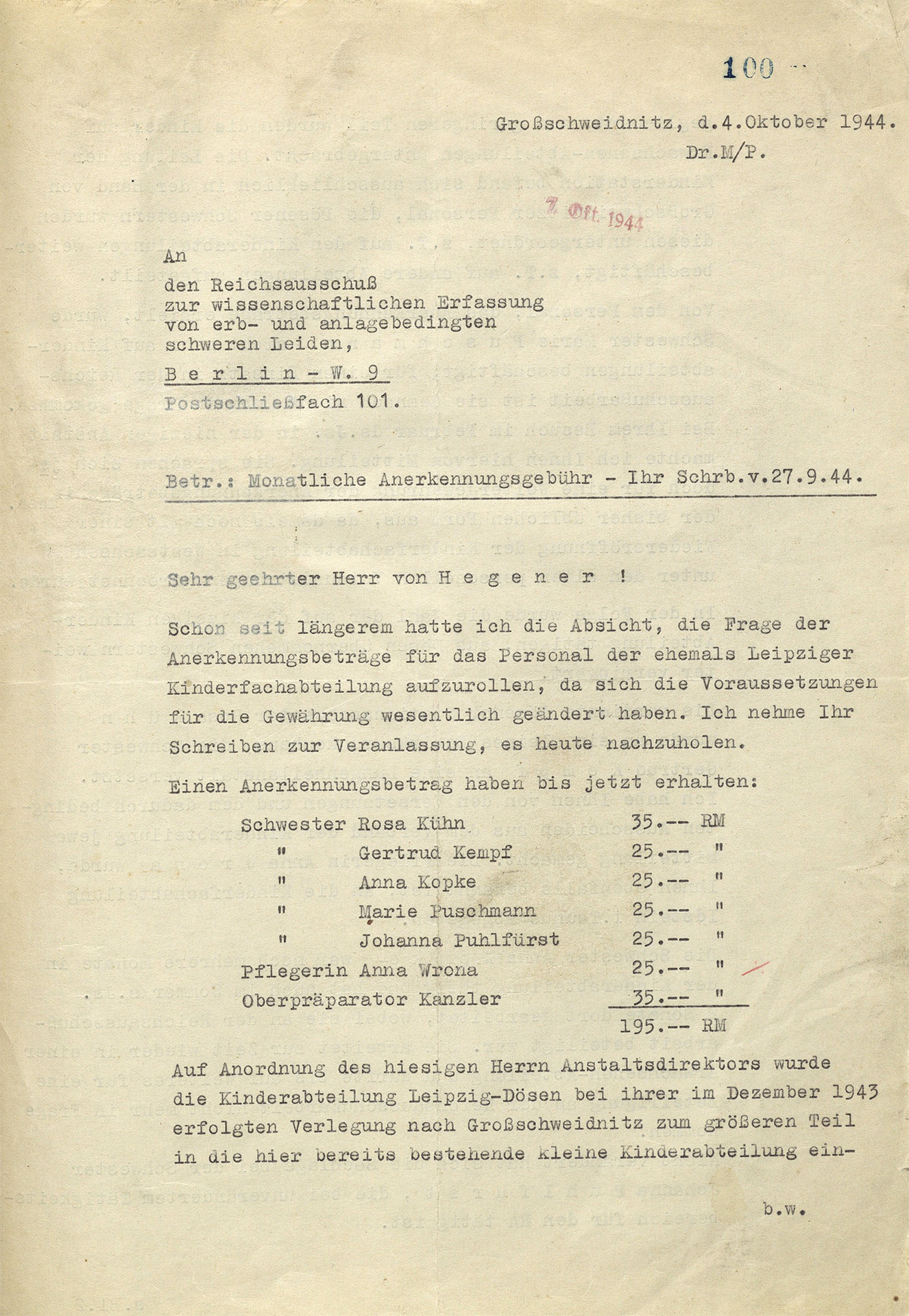

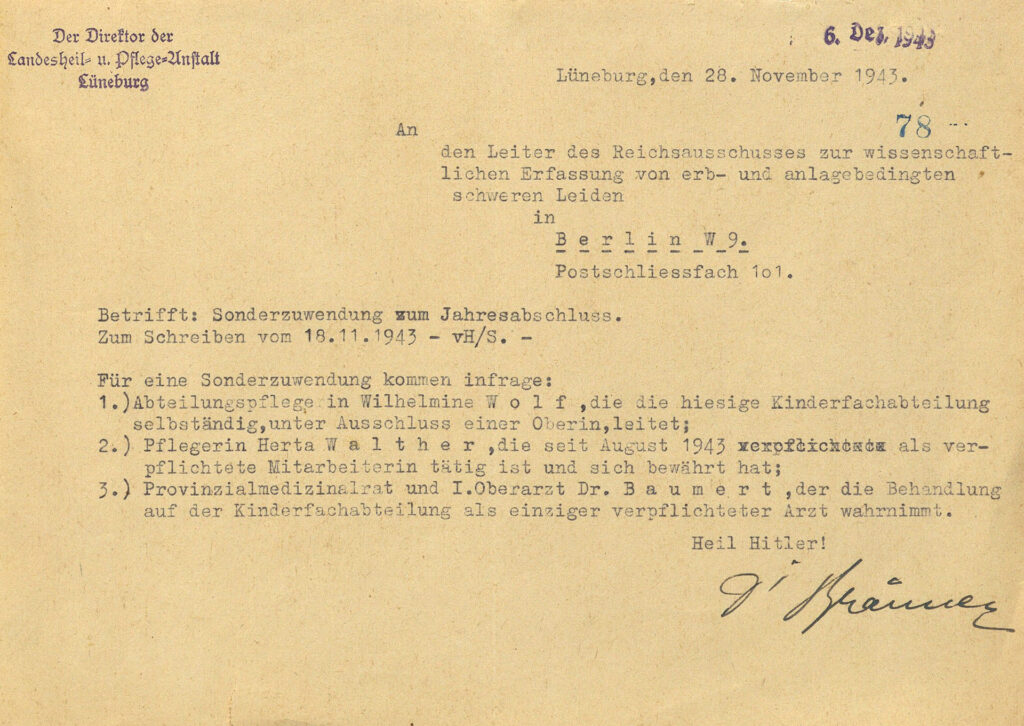

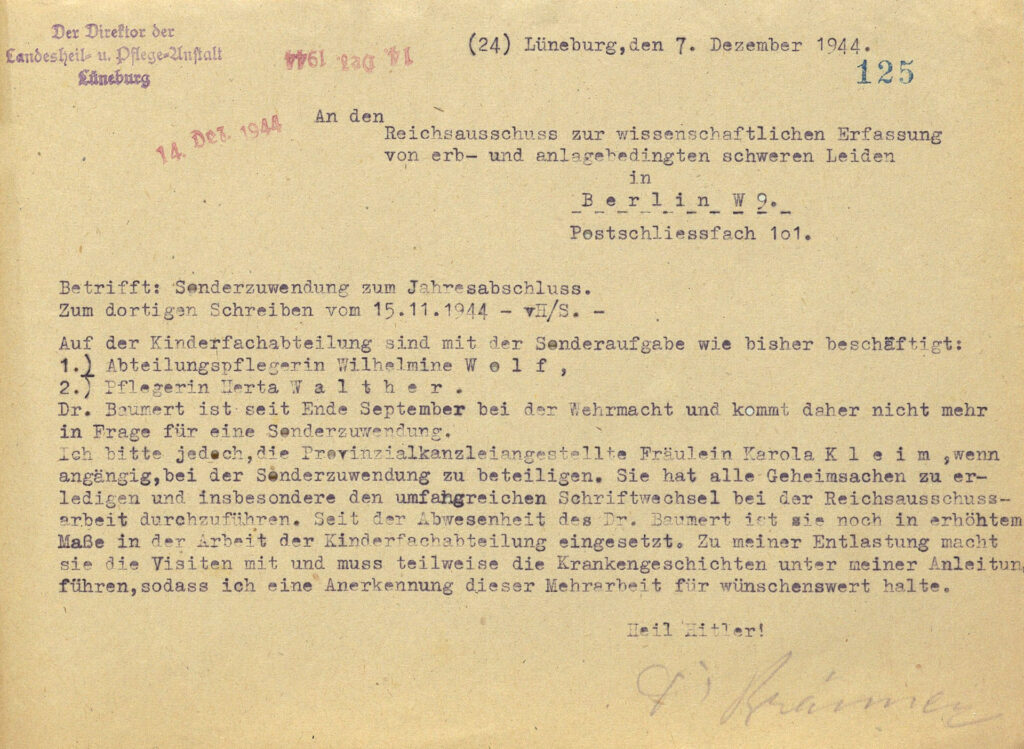

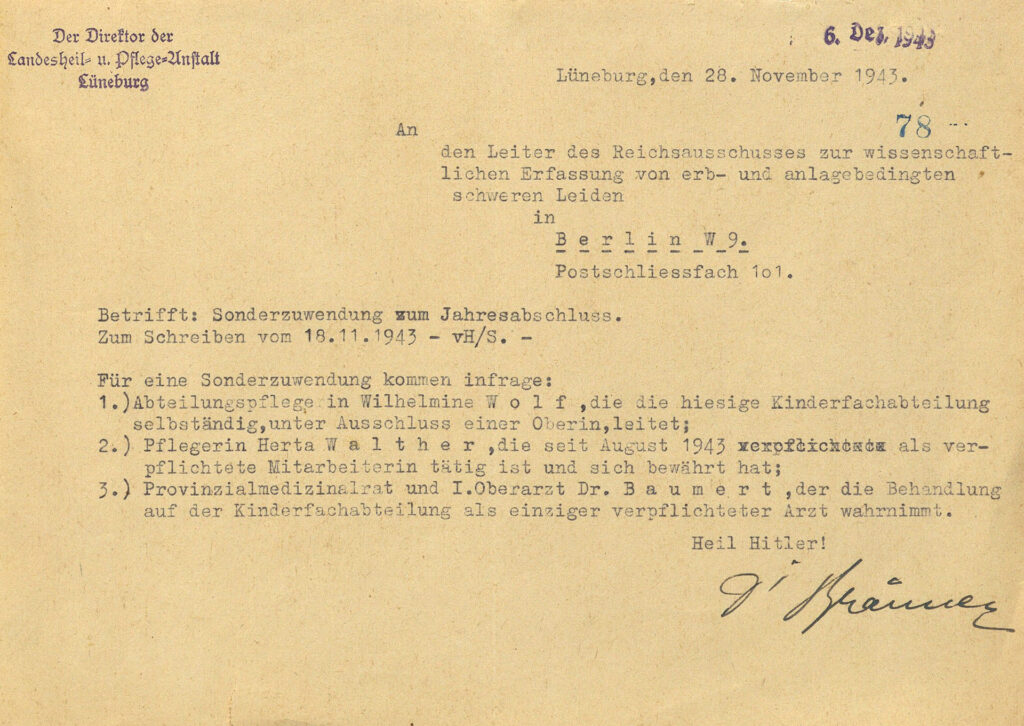

Brief von Max Bräuner an den »Reichsausschuss« vom 28.11.1943.

BArch NS 51/227.

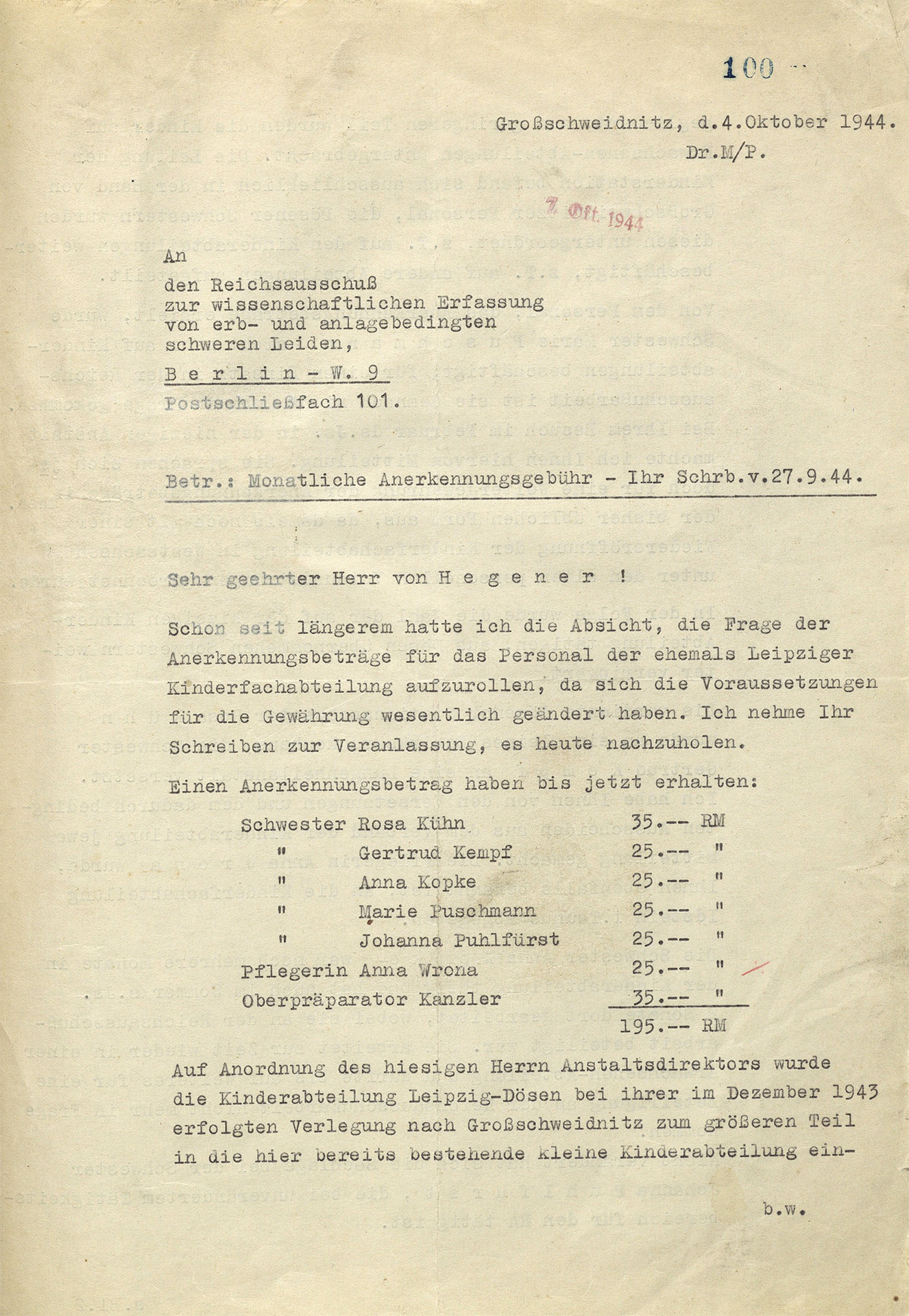

Die Beschäftigten der Lüneburger »Kinderfachabteilung« erhielten 1941 keine »Sonderzuwendungen«. 1942 wurden den Pflegerinnen Wilhelmine Wolf und Dora Vollbrecht jeweils 30 Reichsmark extra ausgezahlt. Für das Jahr 1943 empfahl Max Bräuner die Pflegerinnen Wilhelmine Wolf und Hertha Walther sowie seinen Oberarzt Willi Baumert für zusätzliche Zahlungen. Als Arzt wurde dieser mit 100 Reichsmark belohnt, sodass Lüneburg 1943 insgesamt 160 Reichsmark vom »Reichsausschuss« erhielt.

Das ist ein Brief von dem Arzt Max Bräuner

an den Reichsausschuss.

Max Bräuner schreibt:

Im Jahr 1942 soll es extra Geld geben

für die Pflegerinnen Wilhelmine Wolf und

Dora Vollbrecht.

Im Jahr 1943 soll es extra Geld geben

für die Pflegerinnen Wilhelmine Wolf und

Hertha Walther.

Der Reichsausschuss bezahlt das extra Geld:

Jede Pflegerin bekommen 30 Reichsmark.

Der Arzt Max Bräuner bekommt 100 Reichsmark.

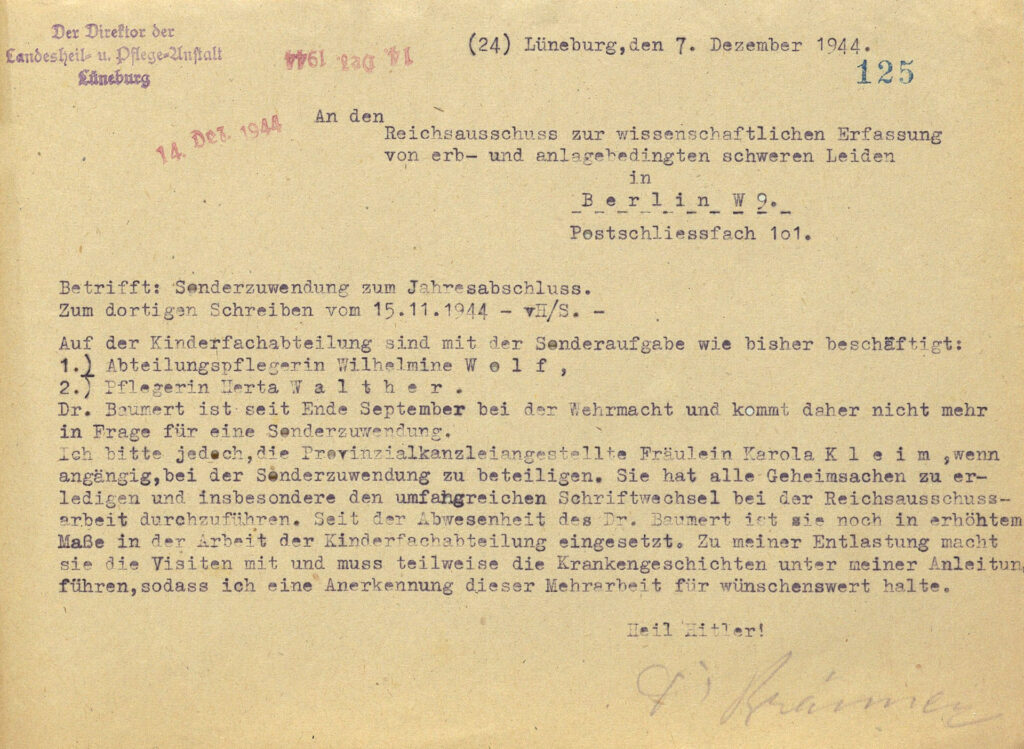

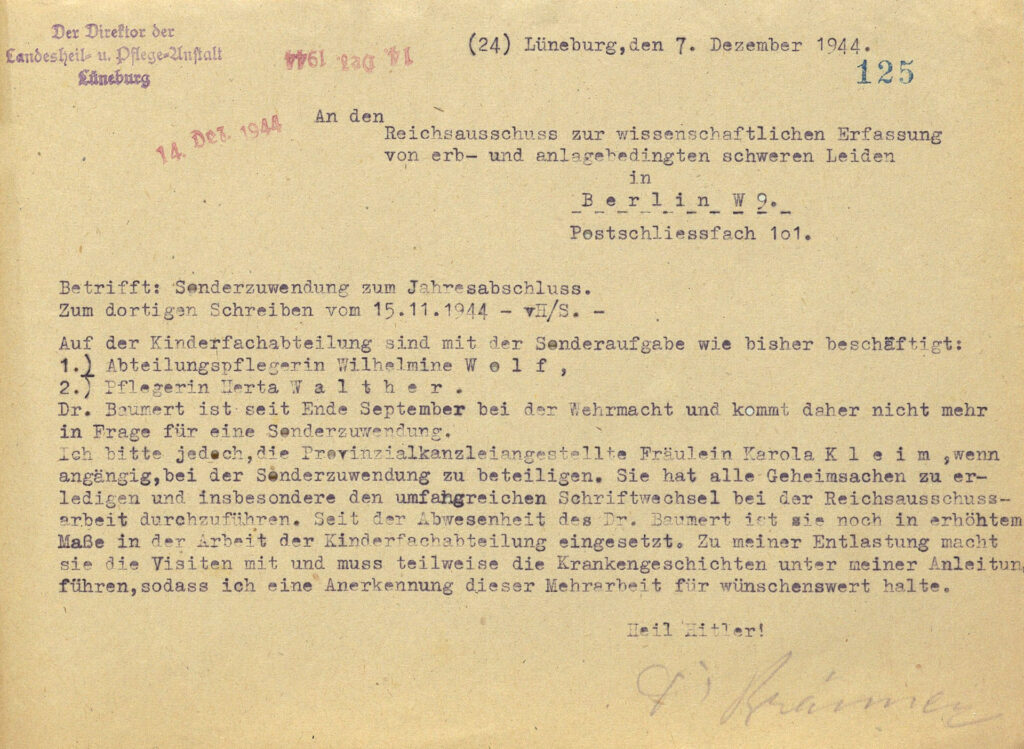

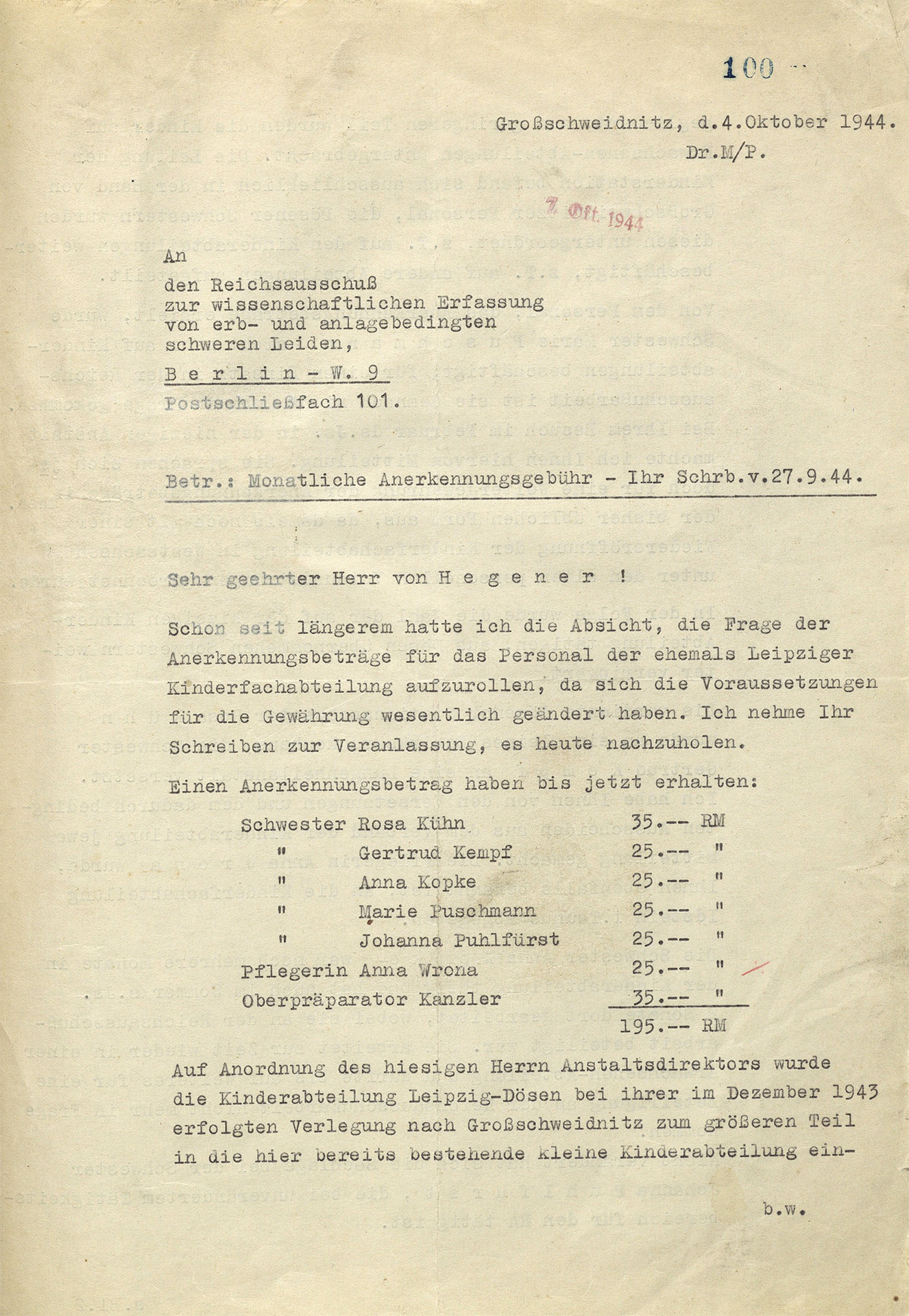

Alle Briefe zwischen dem »Reichsauschuss« und der Anstalt, die Gutachten, die Einträge bei Visiten und die Mitschriften der Leichenöffnungen wurden von der Sekretärin Karola Bierwisch (geb. Kleim) geschrieben. Sie war nicht nur als Sekretärin des Ärztlichen Direktors Max Bräuner, sondern als seine Assistentin bei der tödlichen Forschung beteiligt. Deshalb erhielt sie für das Jahr 1944 ebenfalls eine »Sonderzuwendung« vom »Reichsausschuss«.

Max Bräuner hat eine Büro-Mitarbeiterin.

Sie heißt: Karola Bierwisch.

In der Nazi-Zeit heißt sie: Karola Kleim.

Sie schreibt seine Briefe.

Sie ist bei den Untersuchungen

von den Kindern dabei.

Sie ist die wichtigste Hilfe von Max Bräuner.

Sie macht sogar beim Aufschneiden

von den Leichen mit.

Sie bekommt extra Geld, weil sie so viel hilft.

Das extra Geld kommt vom Reichsausschuss.

Karola Kleim ist eine Ausnahme.

Denn sonst bekommen nur Pflegerinnen und Ärzte extra Geld.

Sie bekommen auch extra Geld,

wenn sie Kinder mit Medikamenten ermorden.

Brief von Max Bräuner an den »Reichsausschuss« vom 7.12.1944.

BArch NS 51/227.

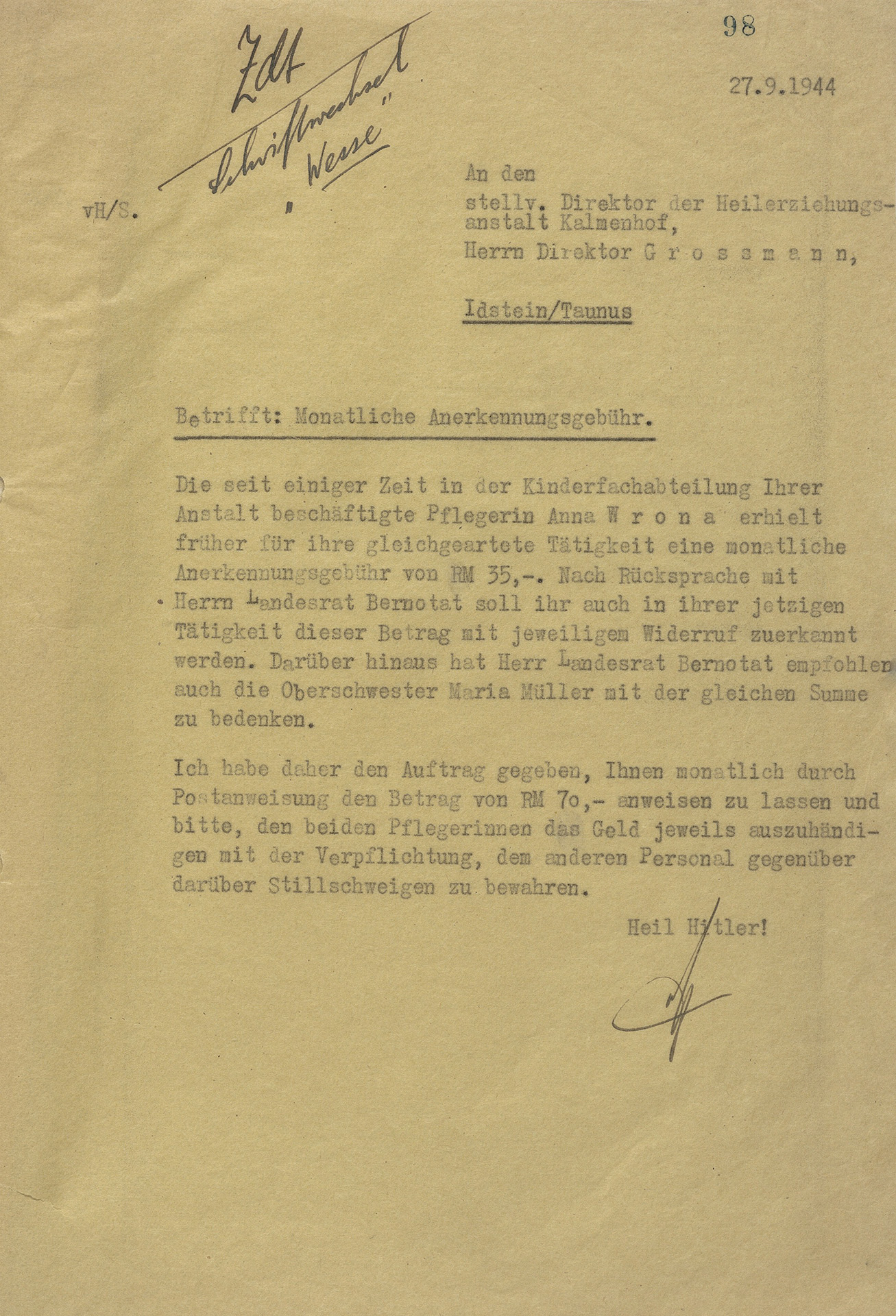

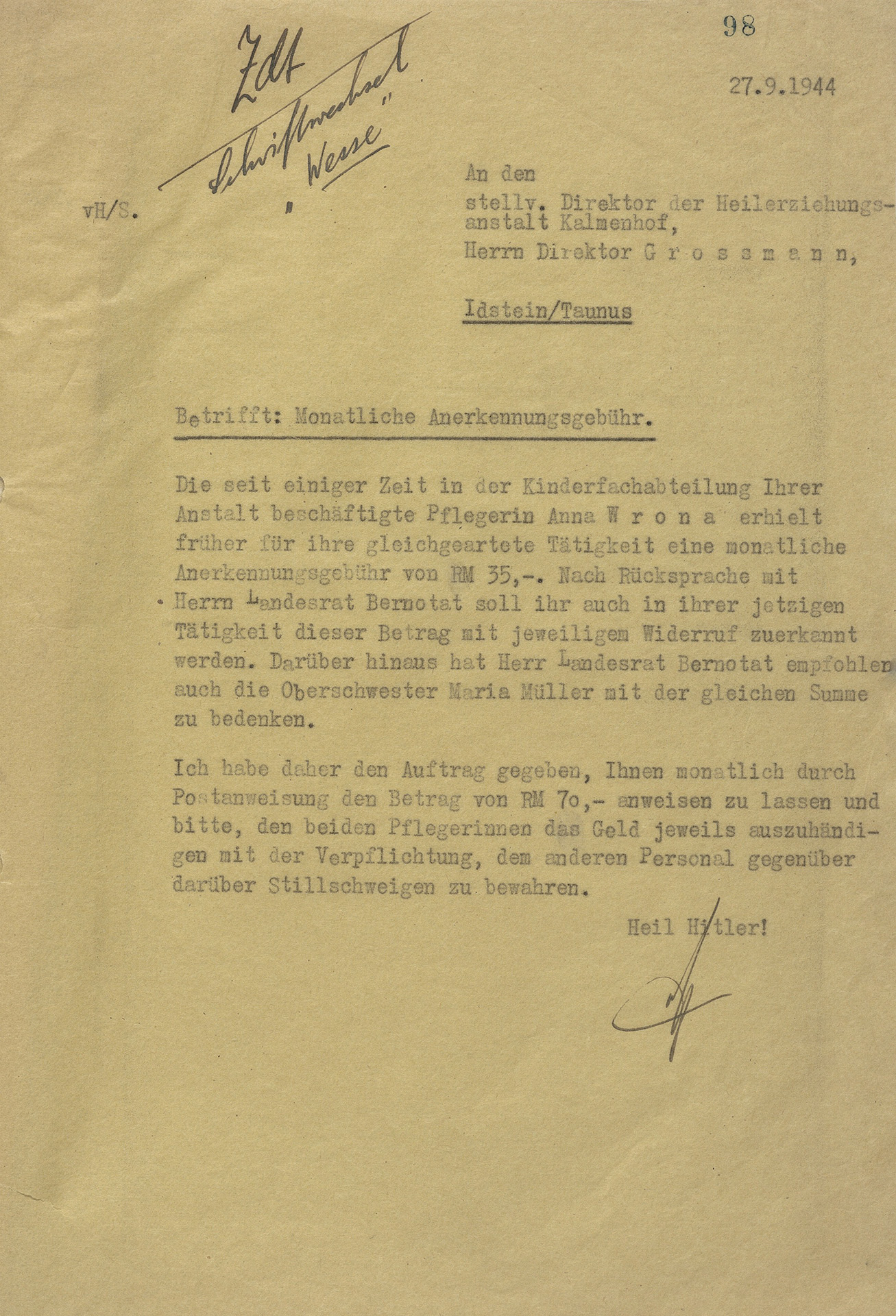

Brief des »Reichsausschusses« an die Heil- und Pflegeanstalt Kalmenhof vom 27.9.1944.

BArch NS 51/227.

Im Jahr 1944 erhielten einzelne Pflegekräfte eine monatliche Zulage in Höhe von 35 Reichsmark für ihre Beteiligung am Krankenmord. Auch die Lüneburger Pflegekräfte erhielten eine solche Zulage. Sie sollte die Loyalität stärken und die Motivation erhöhen.

Einige Pfleger bekommen nicht nur das extra Geld

zu Weihnachten.

Sie bekommen ab dem Jahr 1944 auch mehr Gehalt.

Sie bekommen 35 Reichsmark im Monat mehr.

Sie bekommen mehr Gehalt,

damit sie weitermachen mit den Kinder-Morden.

Brief der Heil- und Pflegeanstalt Großschweidnitz an den Reichsausschuss vom 4.10.1944.

BArch NS 51/227.

Wer sich in der sogenannten »Reichsausschussarbeit« besonders verdient gemacht hatte, erhielt einen Orden. Denjenigen wurde das »Ehrenzeichen für deutsche Volkspflege« verliehen. Die von ihnen verübten Morde wurden auf diese Weise »wertgeschätzt«.

Einige Pfleger strengen sich besonders an.

Sie wollen das Morden besonders gut machen.

Dafür bekommen sie eine Belohnung.

Sie bekommen einen Orden.

Der Orden heißt:

Ein Ehrenzeichen für deutsche Volkspflege.

Der Orden ist für die Kinder-Morde.

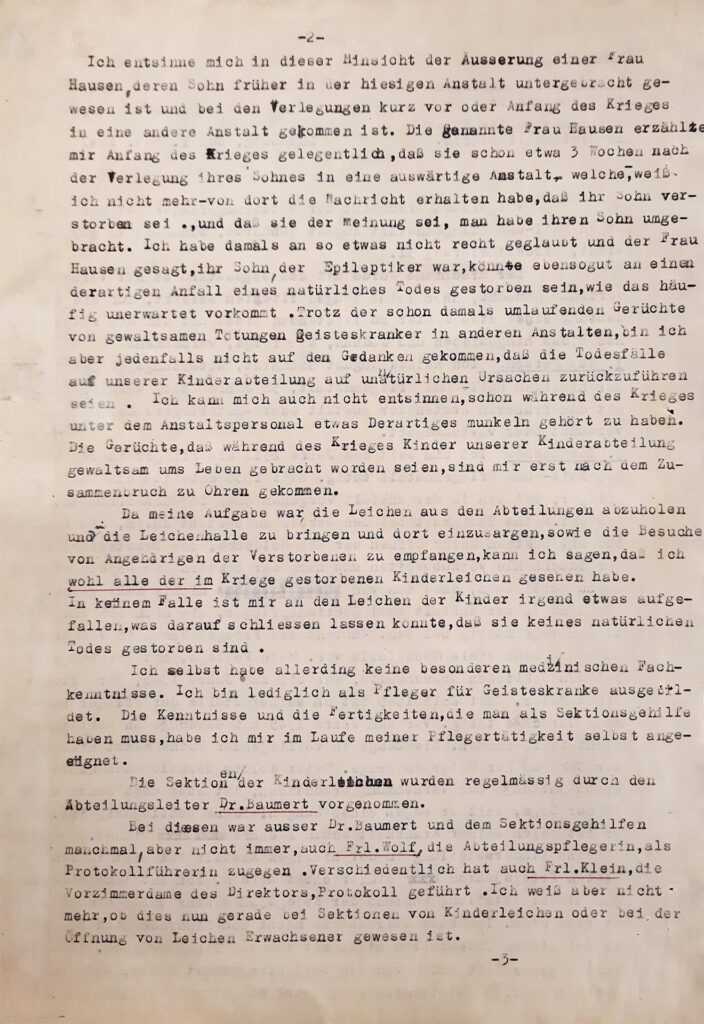

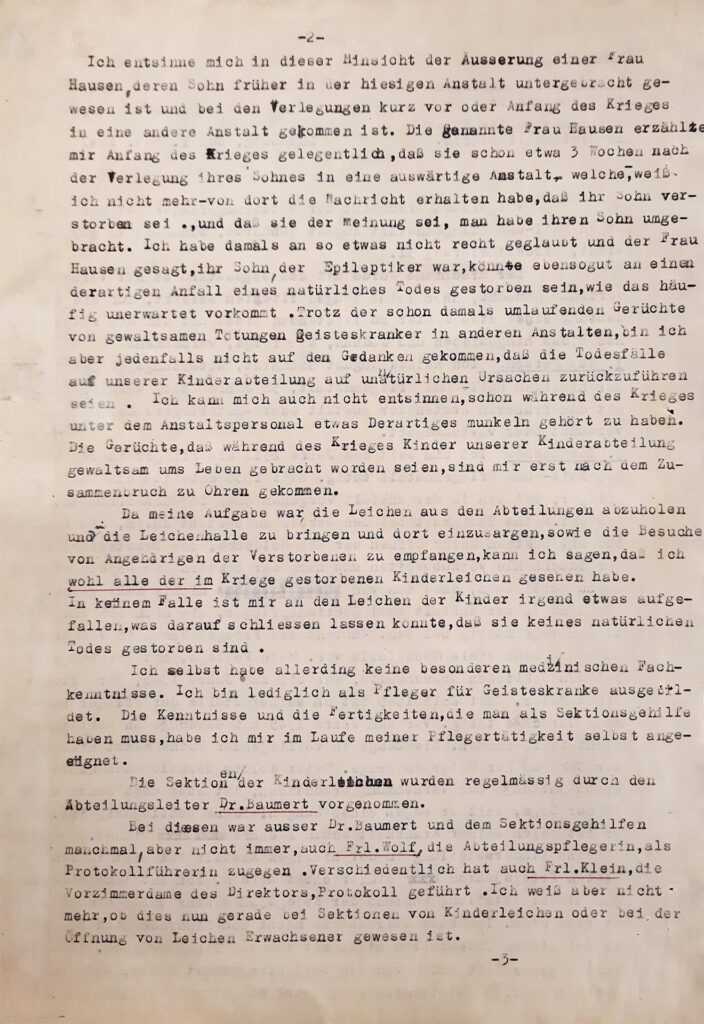

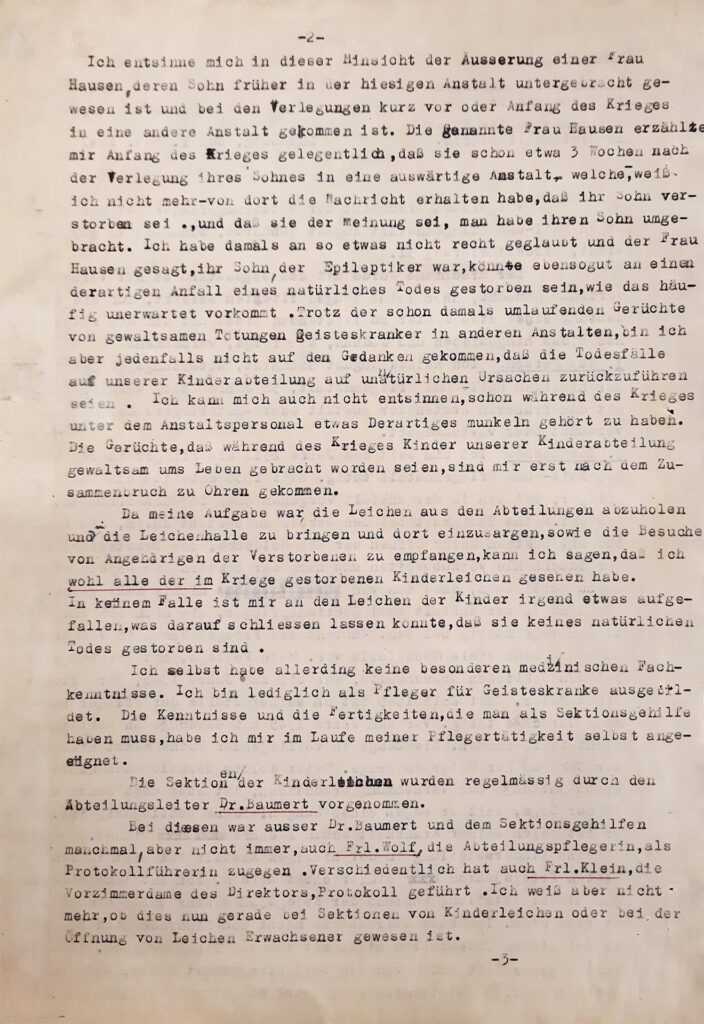

Bei den Leichenöffnungen in der »Kinderfachabteilung« Lüneburg halfen die Pfleger August Gebhardt und Ernst Meier. Gebhardt war seit 1912 Pflegekraft und ab 1938 für die Öffnung und Wiederverschließung der Körper zuständig. Obwohl die Mutter des »T4«-Opfers Paul Hausen ihm sagte, sie denke, ihr Sohn sei ermordet worden, ahnte Gebhardt nicht, dass die vielen von ihm zu bearbeitenden Kinderleichen ebenfalls Opfer des Krankenmordes waren.

August Gebhardt und Ernst Meier sind Pfleger

in der Anstalt in Lüneburg.

Sie helfen beim Aufschneiden von Kinder-Leichen.

August Gebhardt kennt die Mutter von Paul Hausen.

Das Kind Paul Hausen stirbt beim Kranken-Mord.

Die Mutter von Paul Hausen denkt:

Mein Sohn wurde ermordet.

Das erzählt sie dem Pfleger August Gebhardt.

Aber August Gebhardt denkt trotzdem:

Alle Kinder sind ohne Gewalt gestorben.

Sie sind an Krankheiten gestorben

Aber das stimmt nicht.

Auszug aus der Mitschrift der Vernehmung von August Gebhardt vom 1.11.1947.

NLA Hannover Nds. 721 Lüneburg Acc. 8/98 Nr. 3.

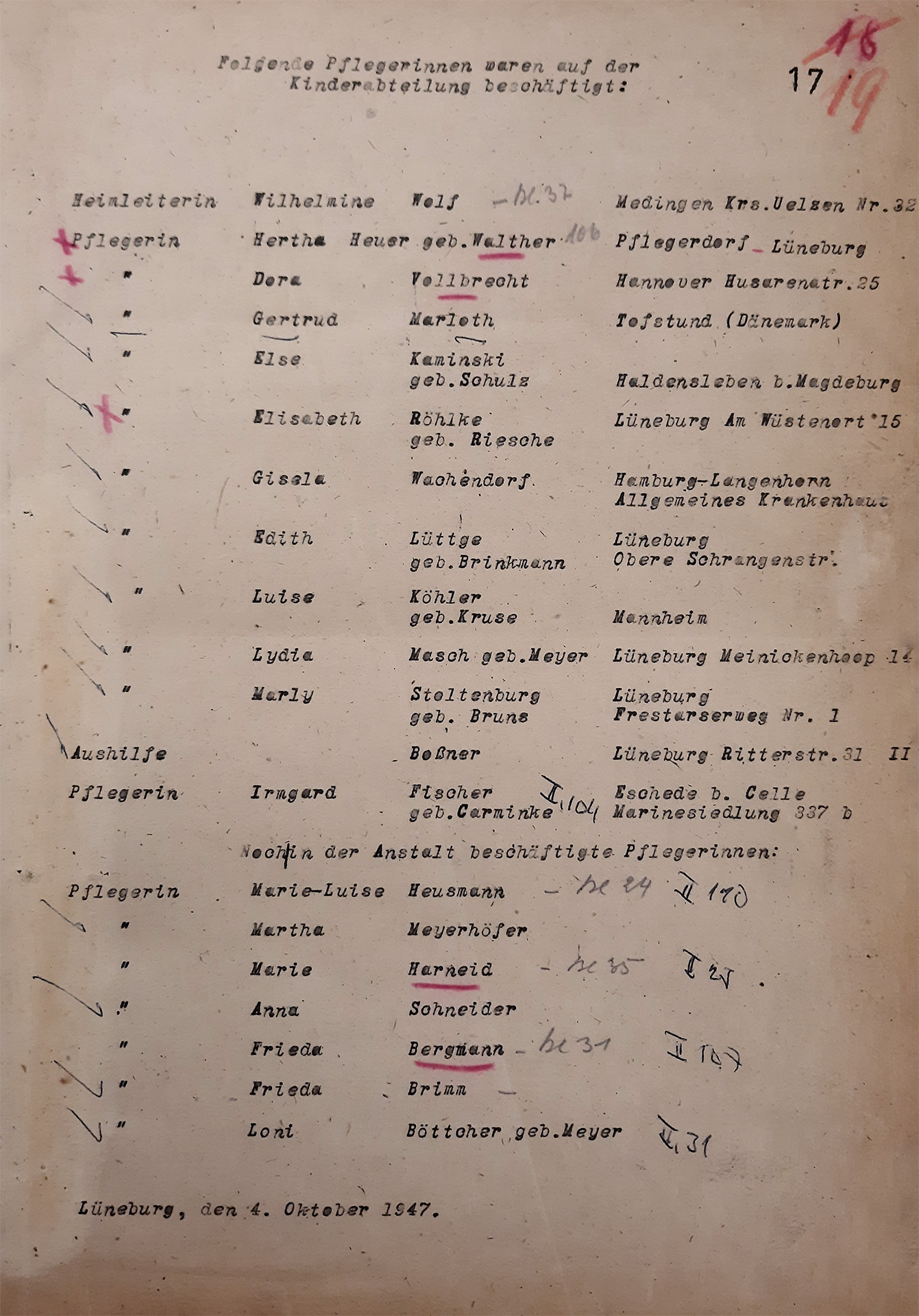

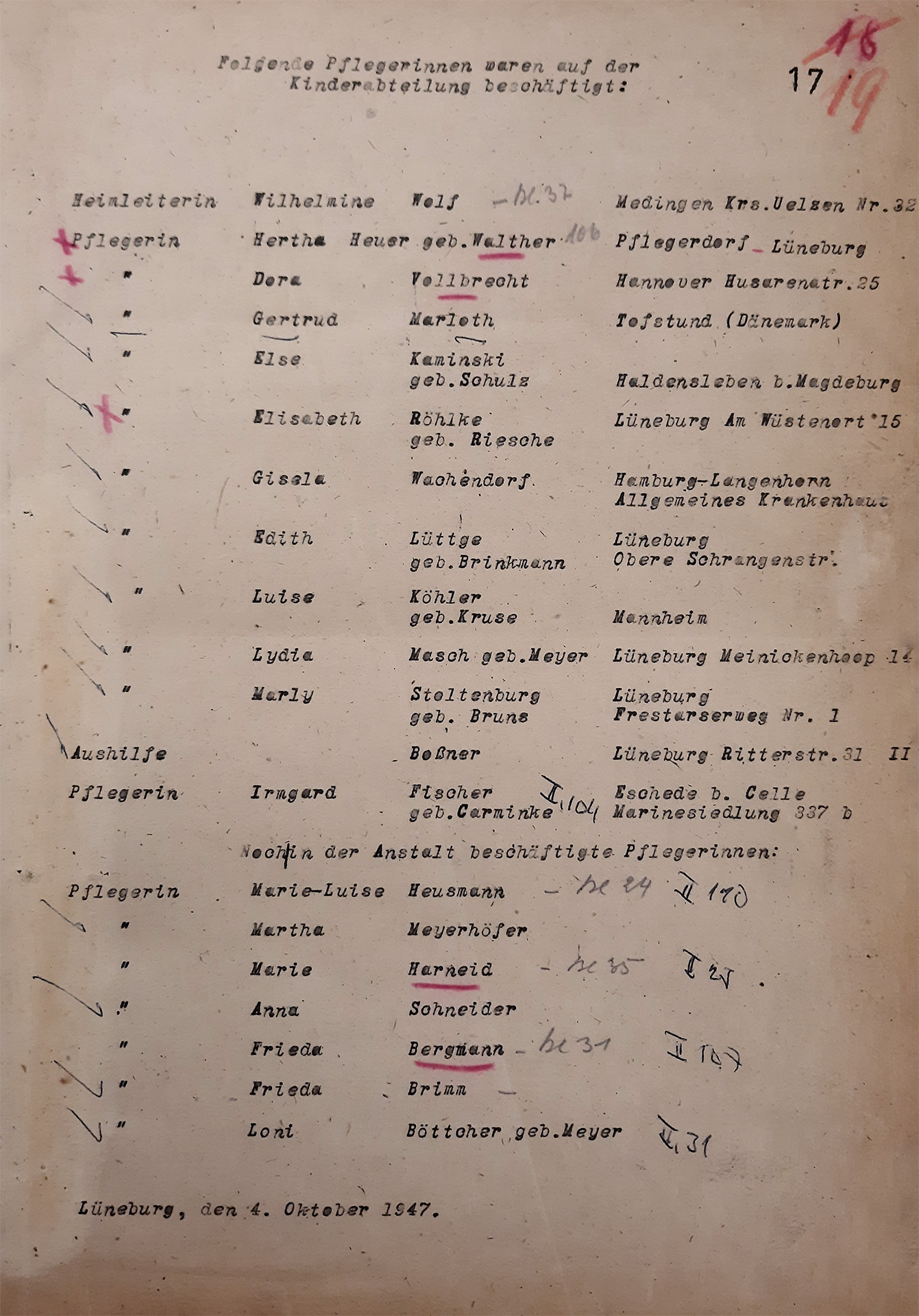

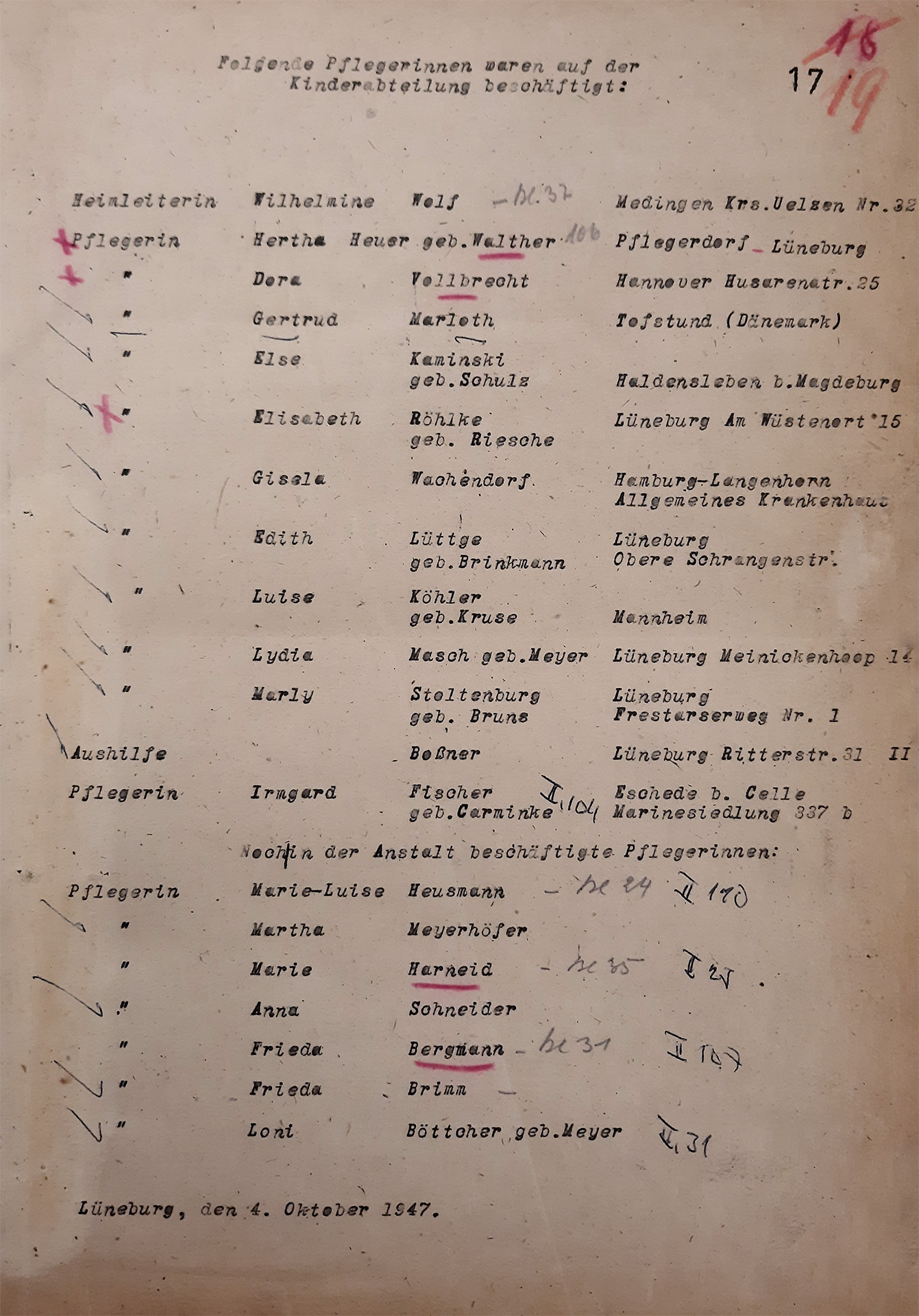

Übersicht der Pflegekräfte in der »Kinderfachabteilung« vom 4.10.1947.

NLA Hannover Nds. 721 Lüneburg Acc. 8/98 Nr. 3.

Die Kinder und Jugendlichen wurden von insgesamt 21 Pflegekräften in drei Schichten betreut und gepflegt. Neben den drei Pflegekräften Wilhelmine Wolf (Oberpflegerin), Ingeborg Weber (sie nahm sich das Leben, daher steht sie nicht auf der Liste) und Dora Vollbrecht, gab es demnach viele weitere Pflegekräfte, die die Kinder und Jugendlichen vernachlässigten und mangelhaft versorgten, ihnen beim Sterben tatenlos zuschauten.

Das ist eine Liste von allen Pflegern

in der Kinder-Fachabteilung.

Die Liste ist aus dem Jahr 1947.

Auf der Liste stehen 20 Pfleger.

Aber es gibt 21 Pfleger.

Die Pflegerin Ingeborg Weber steht nicht mehr

auf der Liste.

Sie hat sich in der Nazi-Zeit selbst getötet.

Sehr viele Pfleger haben mitgemacht

beim Kinder-Mord.

»In der Anstalt habe ich für etwa 130 Kinder 7 Pflegerinnen gleichzeitig im Dienst. Mehr zu stellen ist mit Blick auf die kriegsbedingten Personalschwierigkeiten unmöglich; man fragt sich auch, ob bei der Wertlosigkeit dieses Menschenmaterials in der augenblicklichen Kriegszeit mehr verantwortet werden könne.«

Auszug aus einem Brief von Max Bräuner an das Staatliche Gesundheitsamt Wittmund vom 17.10.1942.

NLA Hannover Hann. 155 Lüneburg Acc. 56/83 Nr. 145, S. 2.

In der »Kinderfachabteilung« Lüneburg gab es 35 Geschwisterkinder aus 15 Familien. Bis zu vier Kinder einer Familie wurden eingewiesen. Manchmal wurden den Eltern alle Kinder genommen. Auch nach dem Krieg kehrten viele Kinder nicht nach Hause zurück. Von den Geschwisterkindern war es nur ein einziges, das seine Eltern wiedersah. Die Jugendlichen wurden ab 1945 an die Jugendfürsorge übergeben. Viele der Überlebenden blieben noch bis in die 1970er-Jahre Bewohnerin und Bewohner der Anstalt.

In der Kinder-Fachabteilung in Lüneburg gibt es

35 Geschwister-Kinder.

Sie sind aus 15 Familien.

Manchmal werden alle Kinder

aus einer Familie ermordet.

Dann ist der Zweite Weltkrieg vorbei.

Nur ein Kind darf wieder nach Hause.

Die anderen Kinder bleiben noch viele Jahre

in der Anstalt

Einige Kinder kommen in ein Jugendheim.

Aber sie kommen nicht zurück nach Hause.

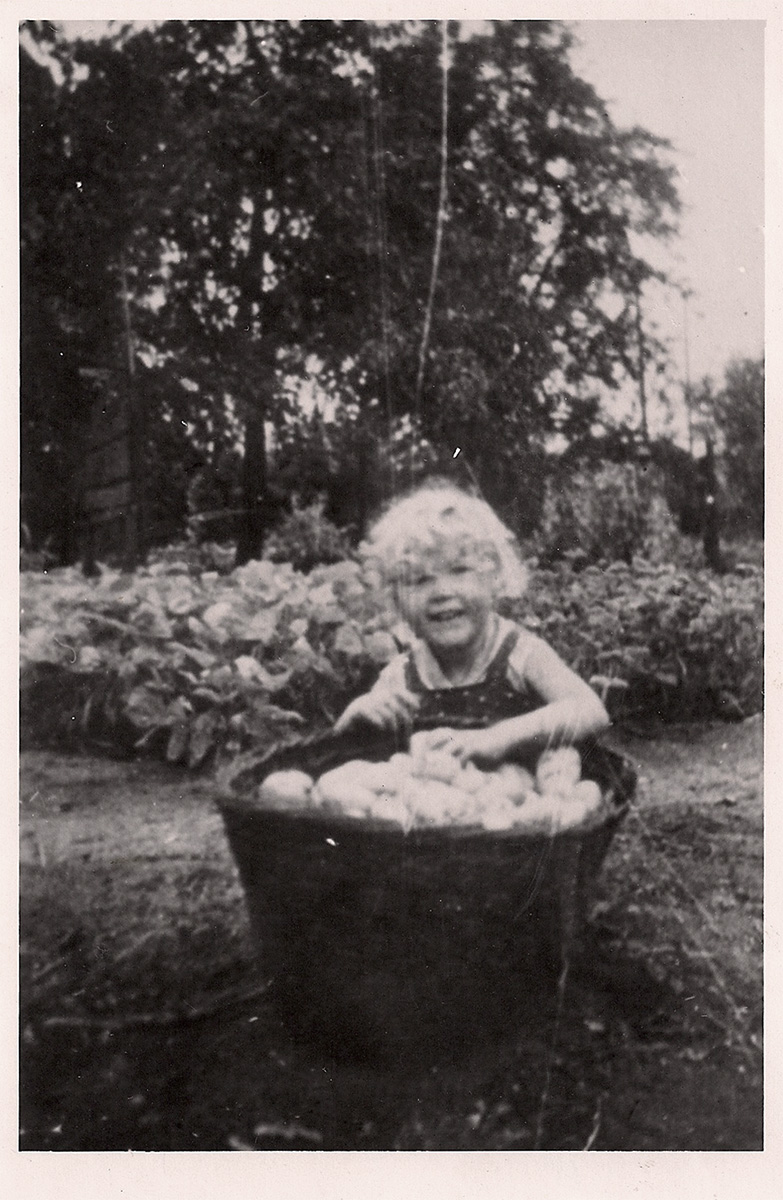

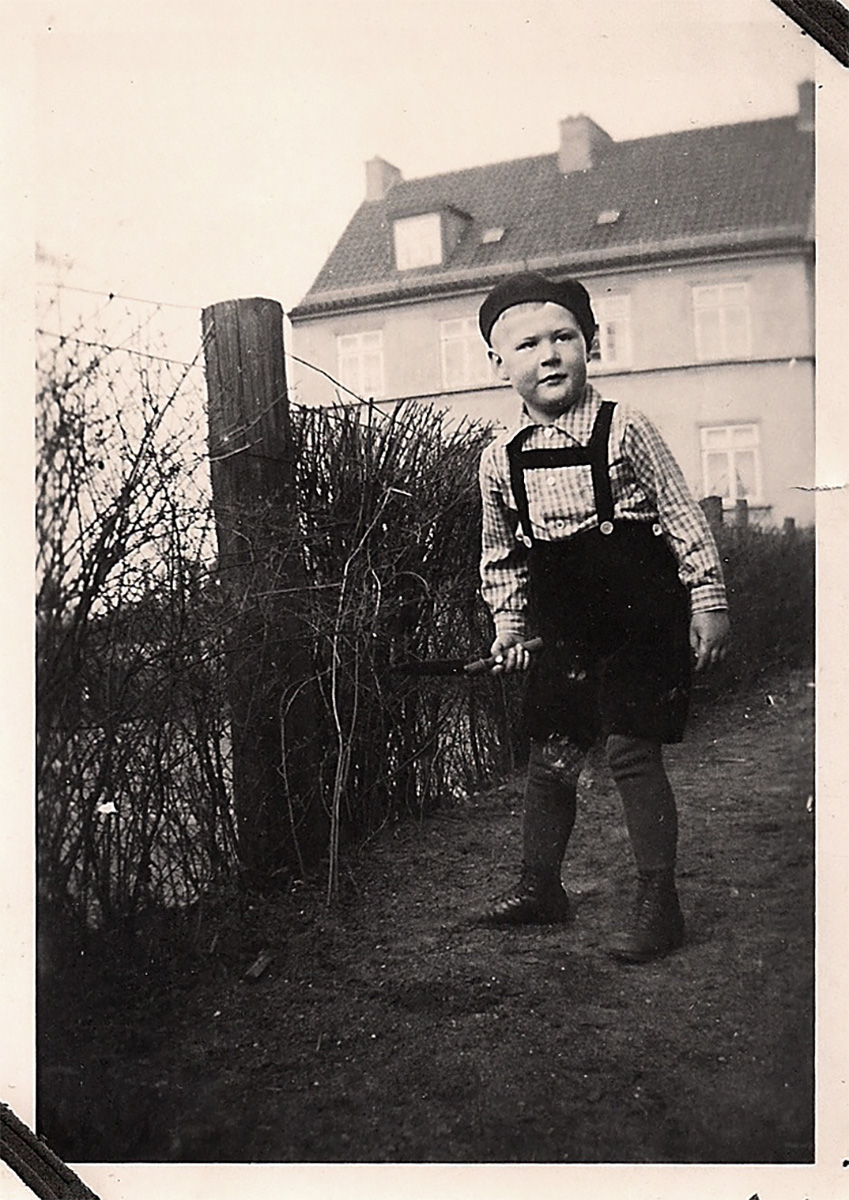

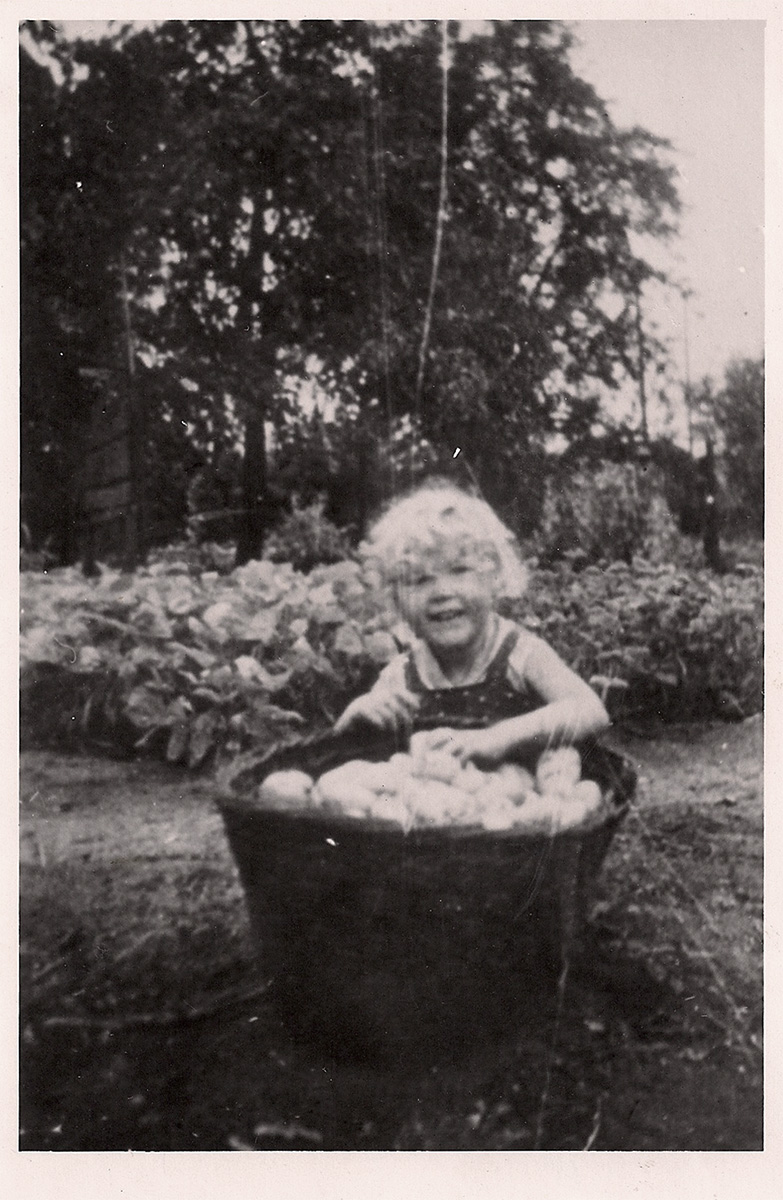

ERIKA (1936 – 1944) UND MARGRET BUHLRICH (1941 – 1945)

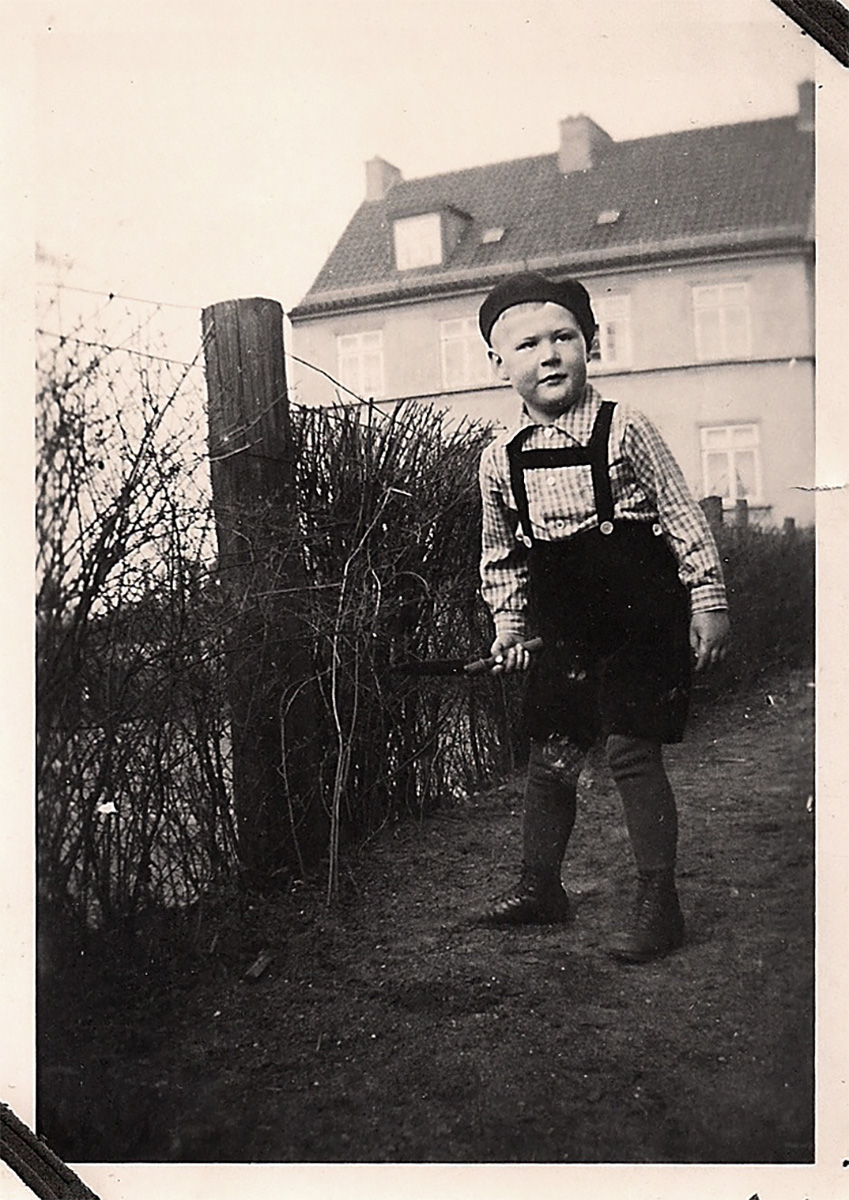

Hans Buhlrich, 1936.

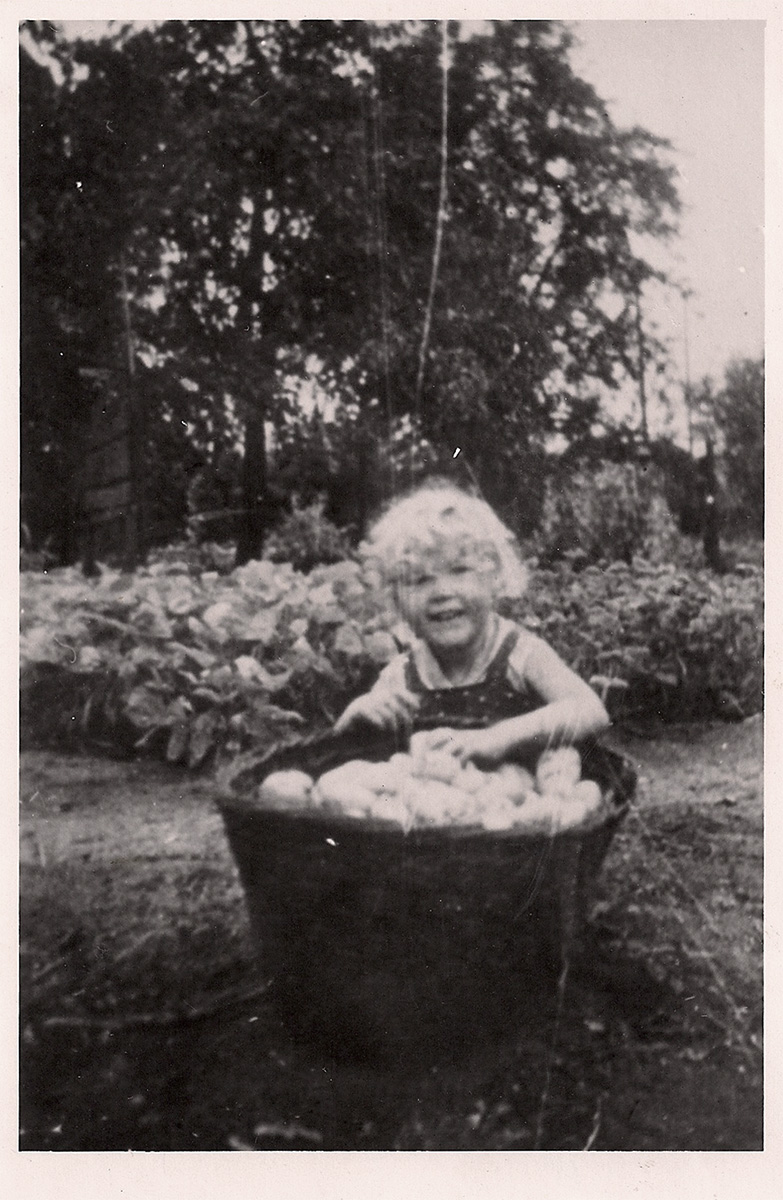

Erika Buhlrich, etwa 1937.

Margret Buhlrich, etwa Sommer 1944.

Privatbesitz Friedrich Buhlrich.

Die Geschwister Buhlrich aus Bremen kamen 1944 in die »Kinderfachabteilung« Lüneburg. Ihr Bruder Hans (1932 – 1942) war bereits 1942 in Kutzenberg (Bayern) gestorben. Er war nach wenigen Tagen aus dem Gertrudenheim bei Bremen evakuiert worden. Die Schwestern wurden rund zwei Jahre später ermordet, um an ihren Gehirnen zu untersuchen, ob eine krankhafte Veranlagung vorläge und die Mutter besser kein viertes Kind bekommen solle. Sie waren bei den Bombardierungen im Luftschutzraum von Nachbarn als störend empfunden worden. Die Mutter war sehr daran interessiert herauszufinden, warum ihr Sohn Hans einen lahmen Arm und ihre beiden Mädchen eine Entwicklungsverzögerung hatten. Um die Ursache herauszufinden starb erst Erika, dann auch Margret. Nachdem die Eltern erfuhren, dass Erika eine Hirnhautentzündung gehabt haben musste, jedoch die Herkunft der anderen Beeinträchtigungen unklar blieb, entschieden die Buhlrichs, kein weiteres Kind zu bekommen. Stattdessen adoptierten sie ein Kind, das aus einer Beziehung einer Deutschen und eines polnischen Zwangsarbeiters hervorgegangen war. Die Existenz von drei leiblichen Geschwistern blieb Friedrich Buhlrich bis zum Tod seiner Adoptiveltern unbekannt.

ERIKA UND MARGRET BUHLRICH

Erika und Margret Buhlrich kommen aus Bremen.

Sie haben einen kranken Bruder.

Er heißt: Hans.

Hans stirbt in Bayern in einem Heim in Kutzenberg.

Die Schwestern von Hans müssen in die Kinder-Fachabteilung in Lüneburg.

Das passiert 2 Jahre nach dem Tod von Hans.

Sie werden ermordet,

damit die Ärzte ihre Gehirne untersuchen können.

Die Ärzte wollen wissen:

Haben die Schwestern die gleiche Krankheit

wie Hans?

Haben die Kinder eine Erbkrankheit von der Mutter? Die Ärzte wollen dann entscheiden,

ob die Mutter ein viertes Kind bekommen darf.

Die Mutter will keine eigenen Kinder mehr.

Sie hat Angst, dass dieses Kind auch krank ist.

Aber die Mutter und der Vater adoptieren ein Kind.

Das Kind heißt Friedrich.

Die Eltern sagen Friedrich nicht,

dass sie vorher schon 3 Kinder hatten.

Das sind 3 Fotos:

Ein Foto von Hans Buhlrich aus dem Jahr 1936.

Ein Foto von Erika Buhlrich aus dem Jahr 1937.

Ein Foto von Margret Buhlrich aus dem Jahr 1944.

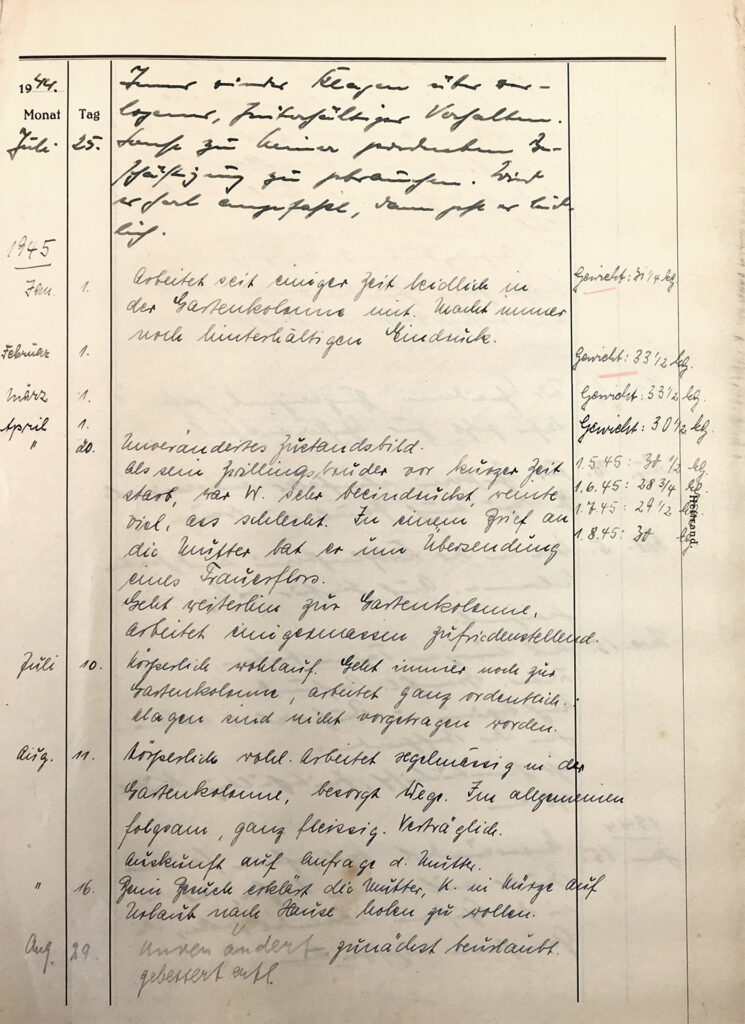

Die Kinder wurden Zeugen des Mordes und sahen ihren Geschwistern beim Sterben zu. So war es auch bei den Köhler-Zwillingen. Herberts Gesundheitszustand verschlechterte sich, im Januar 1945 wog der inzwischen 16-Jährige nur noch 28,5 kg. Er starb am 22. März 1945. Sein Zwillingsbruder Willi war bei ihm. Ihn traf der Verlust hart. Danach arbeitete der Bruder fleißig, sorgte dafür, dass es keine Klagen mehr gab. Er hatte begriffen, dass er nur so überleben konnte.

Einige Kinder müssen zusehen,

wie ihre Geschwister ermordet werden.

So ist es bei den Zwillingen Herbert und Willi Köhler.

Herbert verhungert.

Er bekommt nicht genug zu essen.

Er stirbt.

Sein Bruder Willi muss zusehen.

Er kann Herbert nicht helfen.

Willi ist sehr traurig über Herberts Tod.

Willi nimmt sich vor:

Jetzt arbeite ich viel.

Jetzt mache ich alles richtig.

Nur so kann ich überleben.

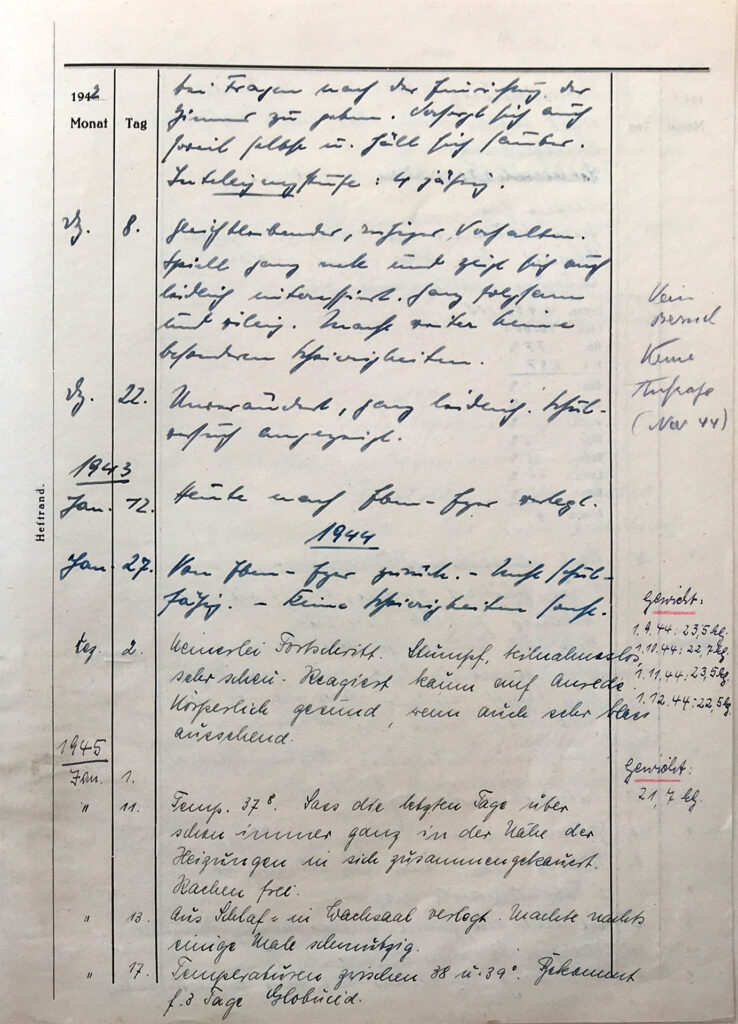

Das ist ein Teil von der Kranken-Geschichte

von Willi Köhler.

Darin steht:

Willi Köhler trauert um seinen Bruder.

Er vermisst seinen Bruder sehr.

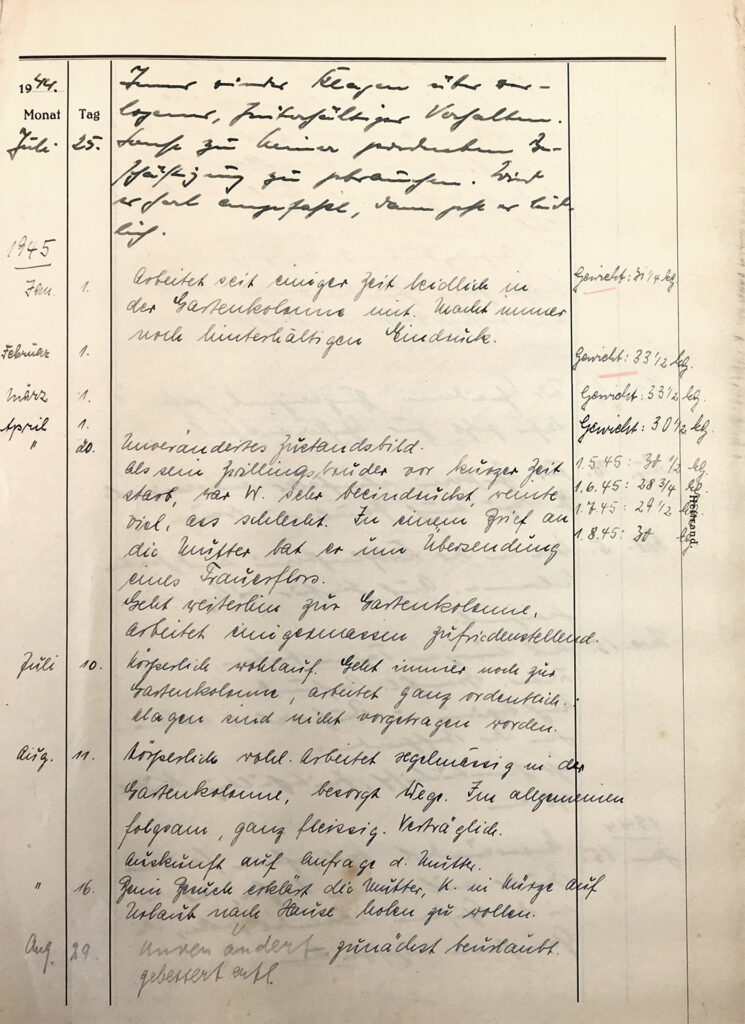

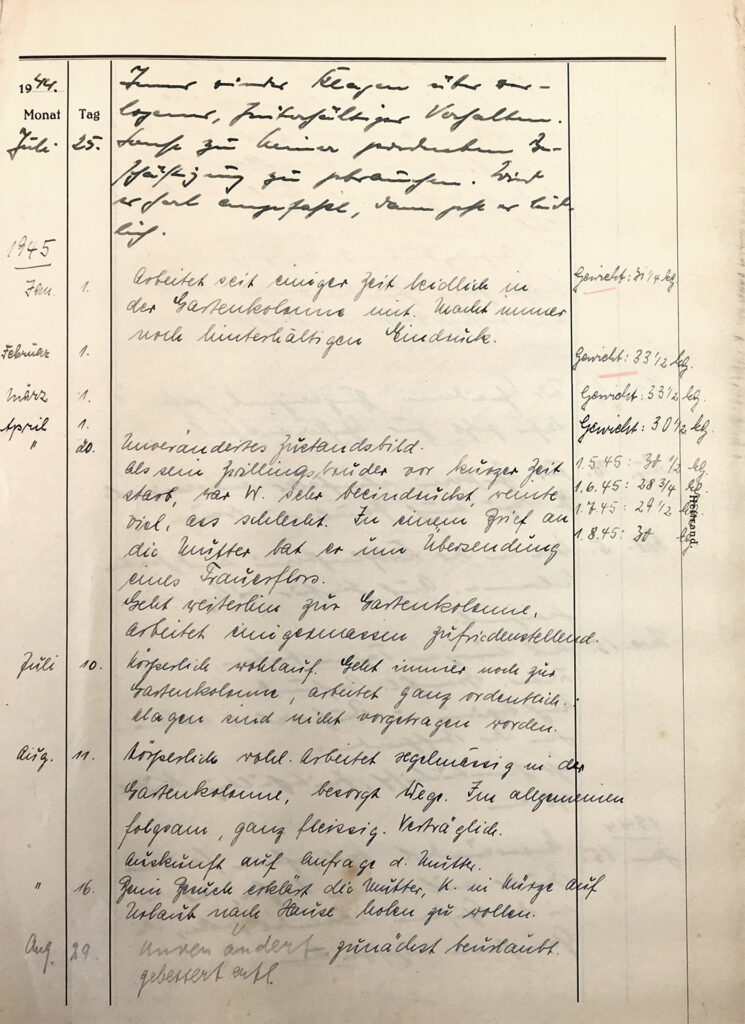

Auszug aus der Krankengeschichte von Willi Köhler.

NLA Hannover Nds. 330 Lüneburg Acc. 2004/134 Nr. 00416.

»Als sein Zwillingsbruder vor kurzer Zeit starb, war W. sehr beeindruckt, weinte viel, ass schlecht. Zu einem Brief an die Mutter bat er um einen Trauerflors.«

Auszug aus der Krankengeschichte von Willi Köhler.

NLA Hannover Nds. 330 Lüneburg Acc. 2004/134 Nr. 00416.

Das ist aus der Kranken-Geschichte von Willi Köhler.

Darin steht:

Willi Köhler ist traurig über seinen toten Bruder.

Er isst nicht mehr.

Er weint viel.

Er will eine schwarze Schleife

für einen Brief für seine Mutter haben.

Dann können alle sehen: Herbert ist tot.

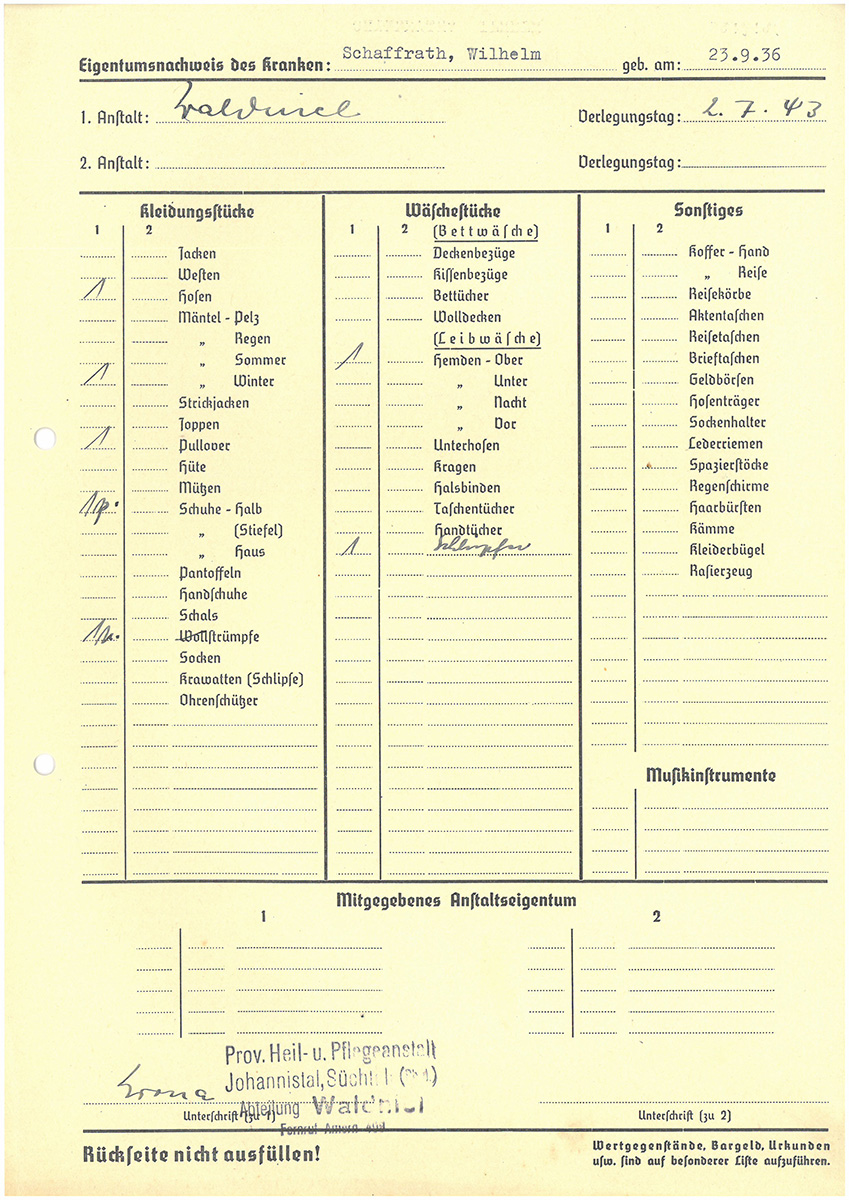

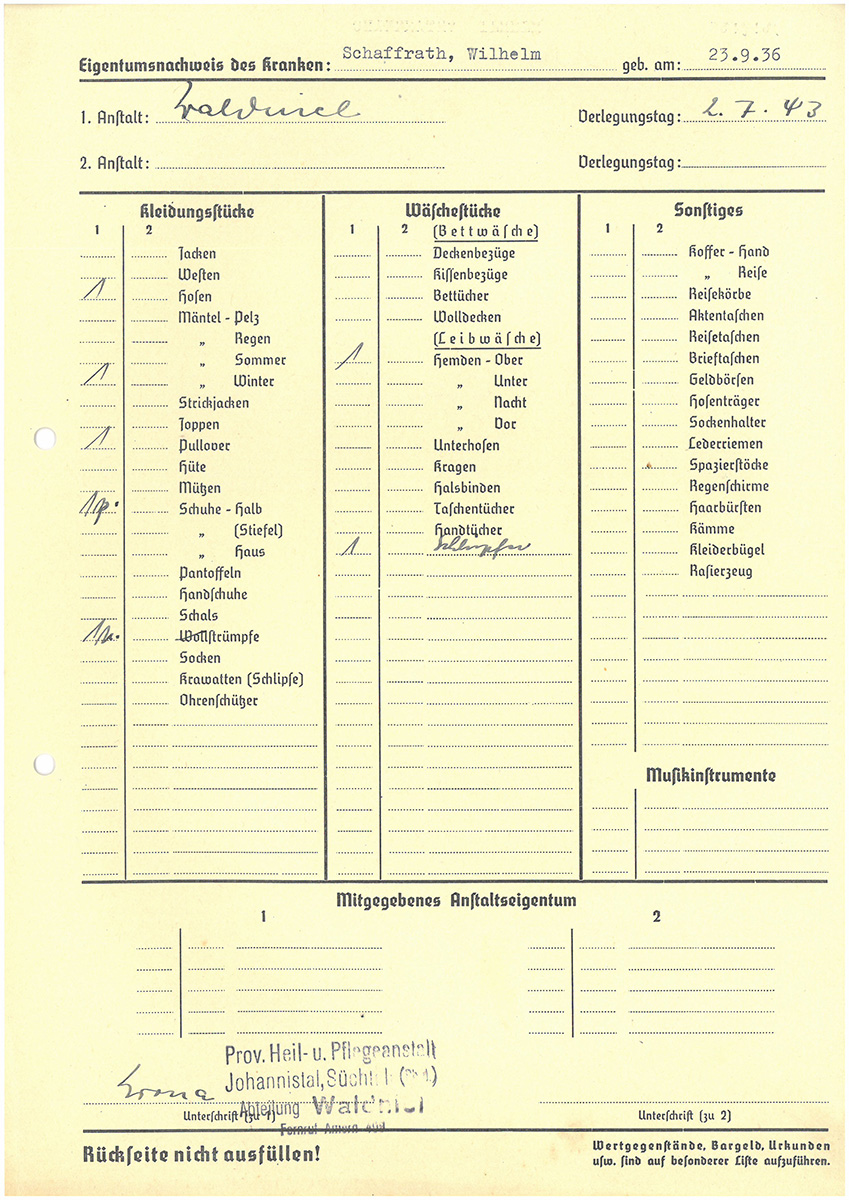

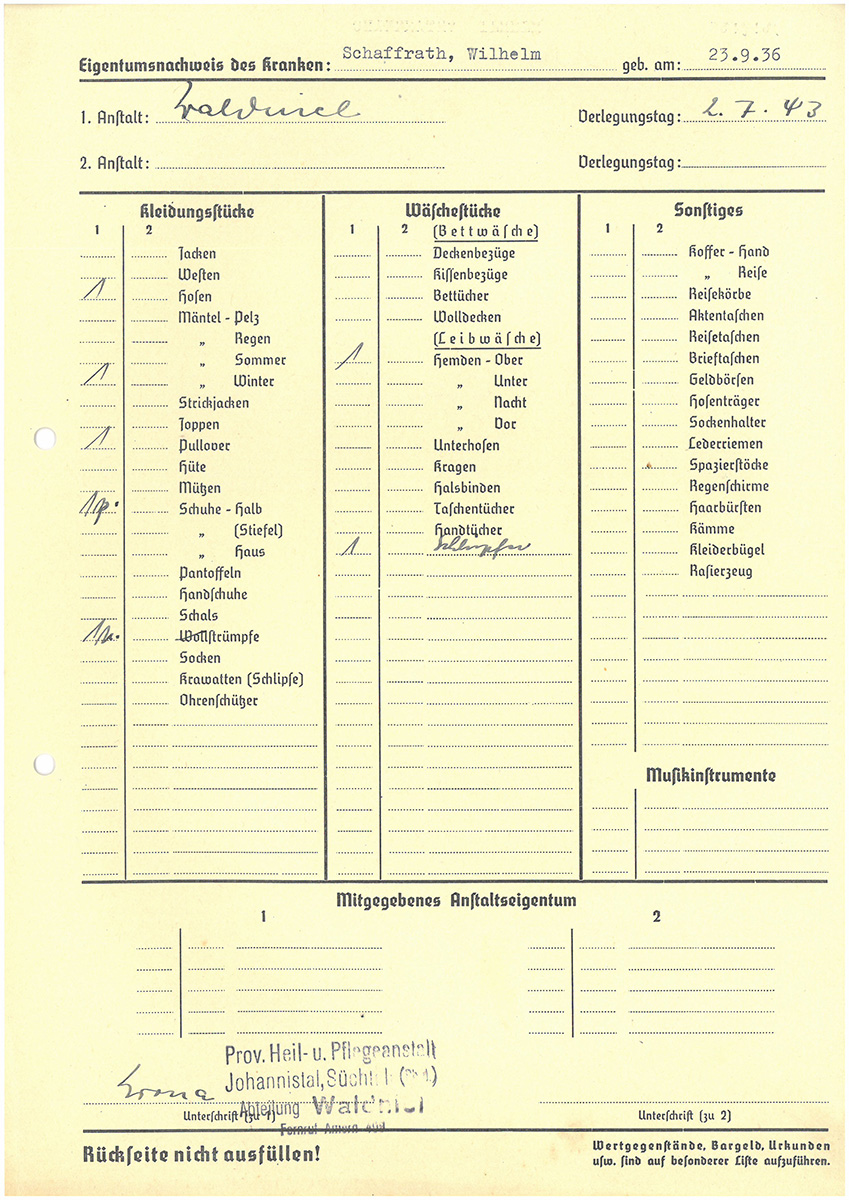

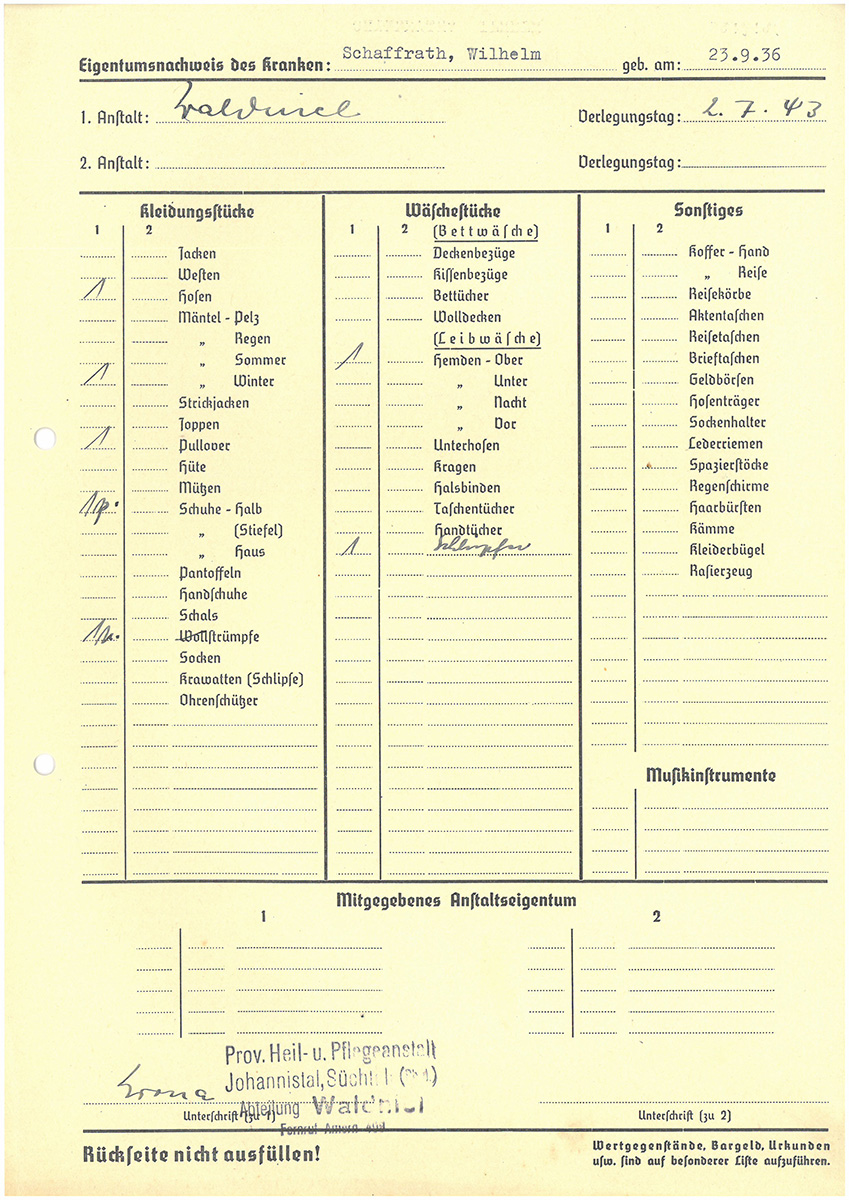

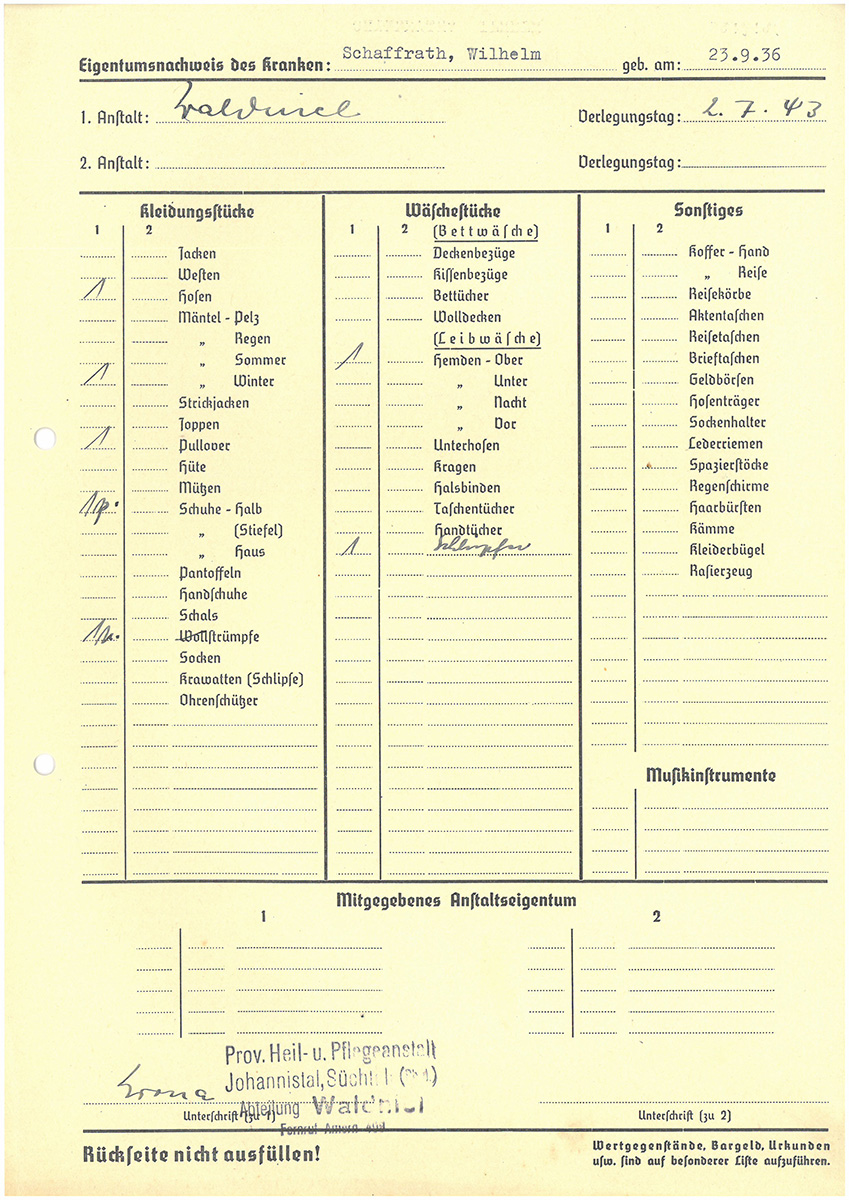

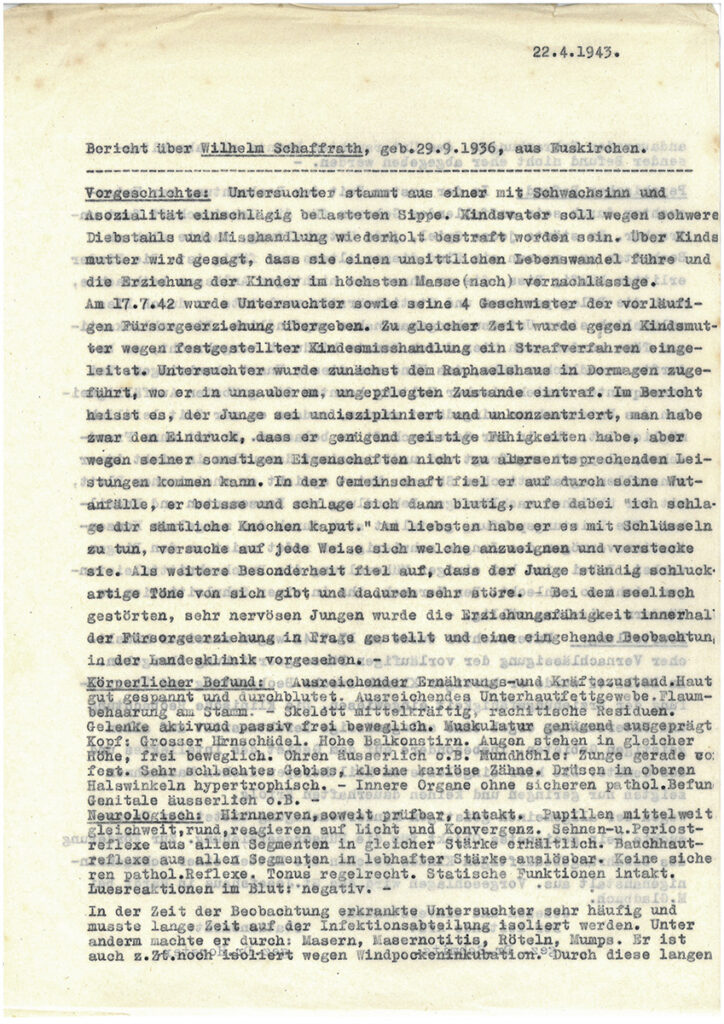

Auszug aus der Krankenakte, Sachenliste von Wilhelm Schaffrath, 1943.

NLA Hannover Hann. 155 Lüneburg Acc. 56/83 Nr. 375.

Anfang Juli 1943 wurde die »Kinderfachabteilung« Waldniel aufgelöst. 183 Kinder und Jugendliche wurden auf die »Kinderfachabteilungen« in Ansbach, Görden, Uchtspringe, Ueckermünde und Lüneburg aufgeteilt. Am 3. Juli 1943 wurden insgesamt 38 Kinder und Jugendliche aus Waldniel in die Lüneburger »Kinderfachabteilung« gebracht. Zwischen Juli 1943 und Dezember 1945 starben mindestens 25, einer von ihnen war Wilhelm Schaffrath.

KINDER AUS WALDNIEL

Im Juli 1943 schließt die Kinder-Fachabteilung

in Waldniel.

Alle Kinder aus Waldniel kommen in andere Anstalten.

Sie kommen nach:

• Ansbach.

• Görden.

• Uchtspringe.

• Ueckermünde.

• Lüneburg.

Die meisten Kinder aus Waldniel kommen

nach Lüneburg.

Es sind 38 Kinder.

25 Kinder aus Waldniel werden in Lüneburg ermordet.

Ein Kind ist Wilhelm Schaffrath.

WILHELM SCHAFFRATH (1936 – 1943)

Auszug aus der Krankenakte, Sachenliste von Wilhelm Schaffrath, 1943.

NLA Hannover Hann. 155 Lüneburg Acc. 56/83 Nr. 375.

Wilhelm Schaffrath aus Euskirchen kam 14 Tage vor Schließung der »Kinderfachabteilung« nach Waldniel. Von der Aufnahme dort bis zu seiner Ermordung in Lüneburg vergingen nur neun Wochen, da er aus Sicht von Willi Baumert als

»völlig gemeinschaftswidrig und lebensunwert«

NLA Hannover Hann. 155 Lüneburg Acc. 56/83 Nr. 375.

bewertet wurde. Er kam nur mit den Kleidungsstücken nach Lüneburg, die er am Körper trug. Mehr hatte man ihm nicht mitgegeben.

WILHELM SCHAFFRATH

Wilhelm Schaffrath kommt aus Euskirchen.

Er kommt in die Kinder-Fachabteilung nach Waldniel.

14 Tagen später macht die Kinder-Fachabteilung

in Waldniel zu.

Wilhelm Schaffrath kommt

in die Kinder-Fachabteilung nach Lüneburg.

Er bringt nichts mit aus Waldniel.

Er hat nur die Kleidung, die er trägt.

Das ist alles, was er hat.

Willi Baumert sagt:

Wilhelm Schaffrath ist dumm.

Er kann nicht mit vielen Menschen zusammen sein.

Wilhelm Schaffrath war im Alter von sechs Jahren zusammen mit seinen vier Geschwistern in die Fürsorgeerziehung gekommen. Sie hatten zu Hause viel Gewalt erlebt. Auch in der Fürsorgeerziehung hörte die Gewalt nicht auf. Wilhelm wurde als »erziehungsunfähig« in die »Kinderfachabteilung« zwangseingewiesen.

Wilhelm Schaffrath hat 4 Geschwister.

Zu Hause gibt es viel Gewalt.

Man holt ihn und seine Geschwister

aus der Familie raus.

Da ist Wilhelm 6 Jahre alt.

Wilhelm kommt in ein Heim.

Dort gibt es auch Gewalt.

Er kommt in die Kinder-Fachabteilung nach Lüneburg.

Nach 9 Wochen ist Wilhelm tot.

Er stirbt durch den Kinder-Mord.

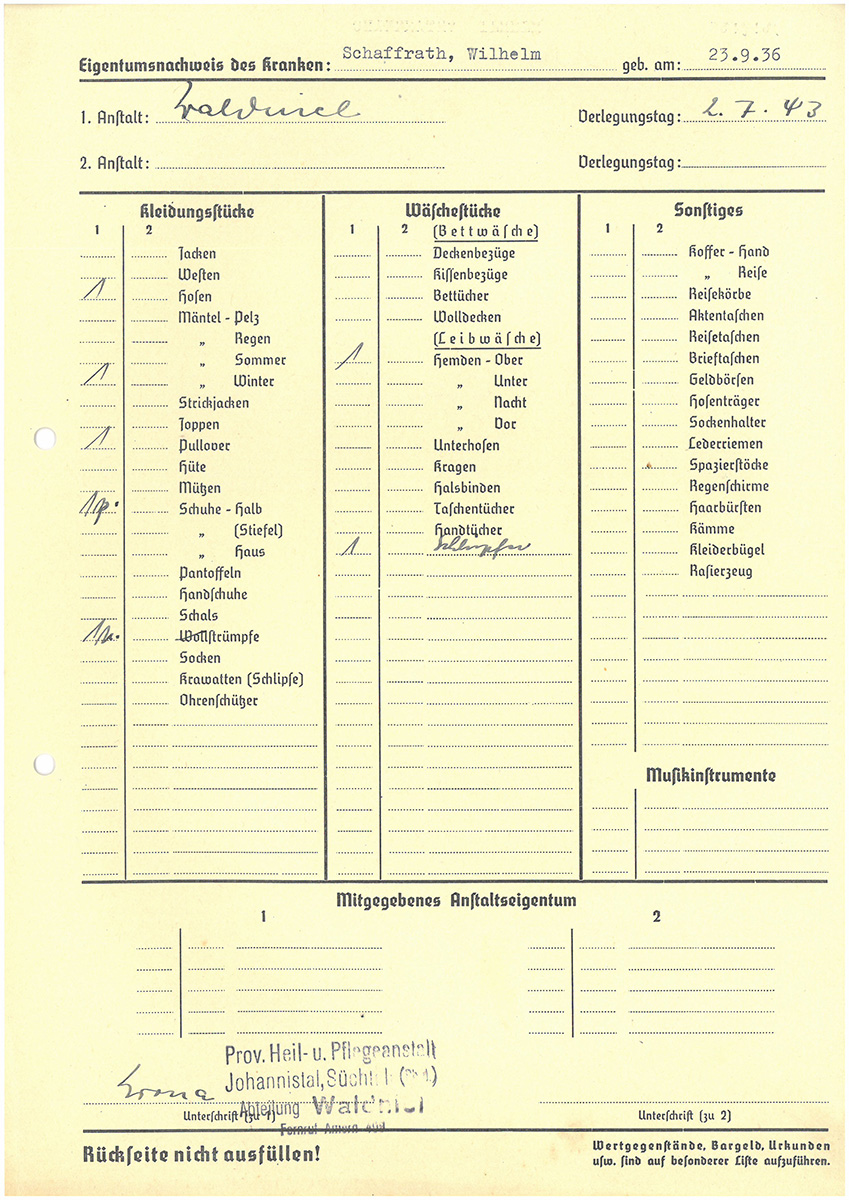

Das ist ein Bericht

über Wilhelm Schaffrath aus dem Jahr 1943.

In dem Bericht steht,

was Wilhelm in der Nazi-Zeit erlebt.

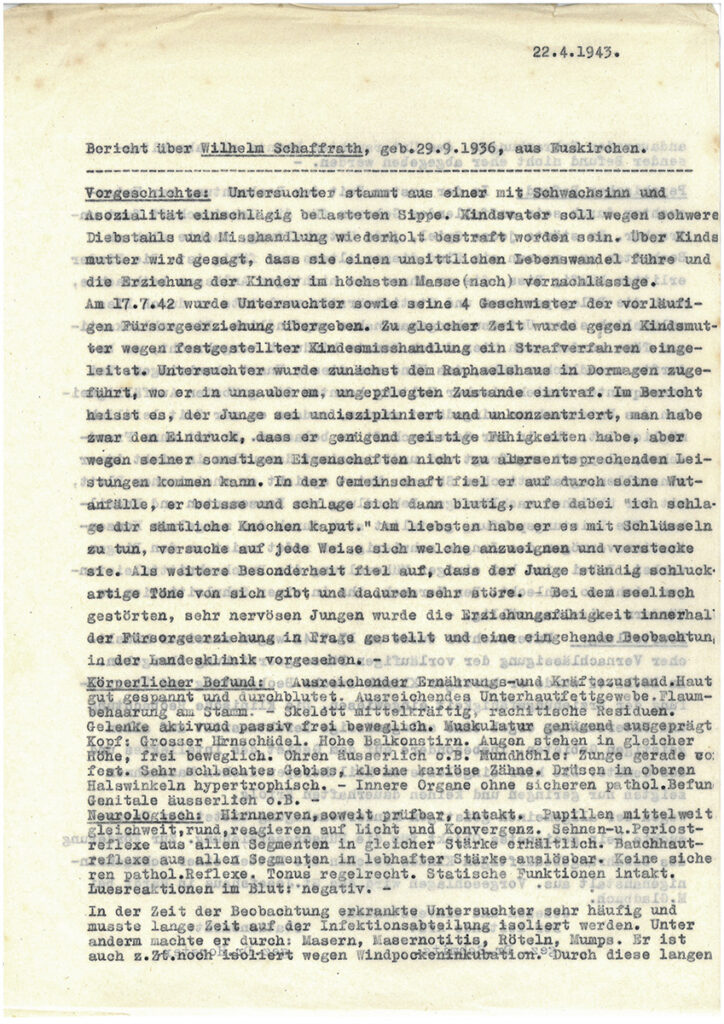

Auszug aus dem Bericht der Fürsorgeerziehung vom 22.4.1943.

NLA Hannover Hann. 155 Lüneburg Acc. 56/83 Nr. 375.

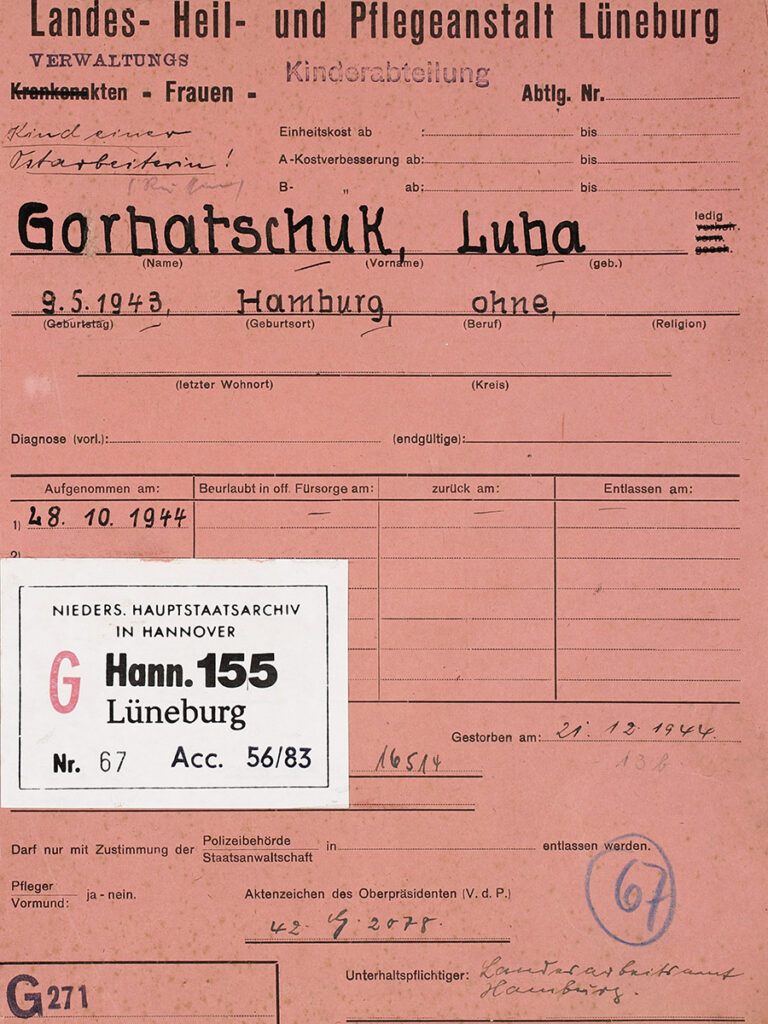

Ab 1944 nahm die »Kinderfachabteilung« Lüneburg etwa zehn Kinder aus den Niederlanden und Belgien auf. Sie waren mit oder ohne Eltern geflüchtet und wurden von Helfer*innen der NSV (Nationalsozialistische Volkswohlfahrt) für die Aufnahme in die »Kinderfachabteilung« gemeldet. Andere waren Kinder von Zwangsarbeiterinnen aus Russland, den sowjetischen Teilstaaten und Polen. Sie kamen mit ihren Müttern zunächst in die »Ausländersammelstelle« oder waren den Müttern im Lager weggenommen worden.

Viele Kinder sind in der Kinder-Fachabteilung

in Lüneburg.

Es gibt auch Kinder in der Kinder-Fachabteilung, die nicht aus Deutschland sind.

Sie kommen zum Beispiel aus West-Europa:

aus Belgien oder aus den Niederlanden.

Diese Kinder sind Flüchtlinge.

Sie müssen weg aus ihrer Heimat.

Einige Kinder kommen allein nach Deutschland.

Einige Kinder kommen zusammen mit ihren Eltern nach Deutschland.

Auch Kinder aus Ost-Europa kommen in die Anstalt nach Lüneburg: aus Russland, aus der Ukraine und

aus Polen.

Sie sind oft Kinder von Zwangs-Arbeitern.

Oder sie kommen aus einem Lager.

Dort hat man sie den Müttern weggenommen.

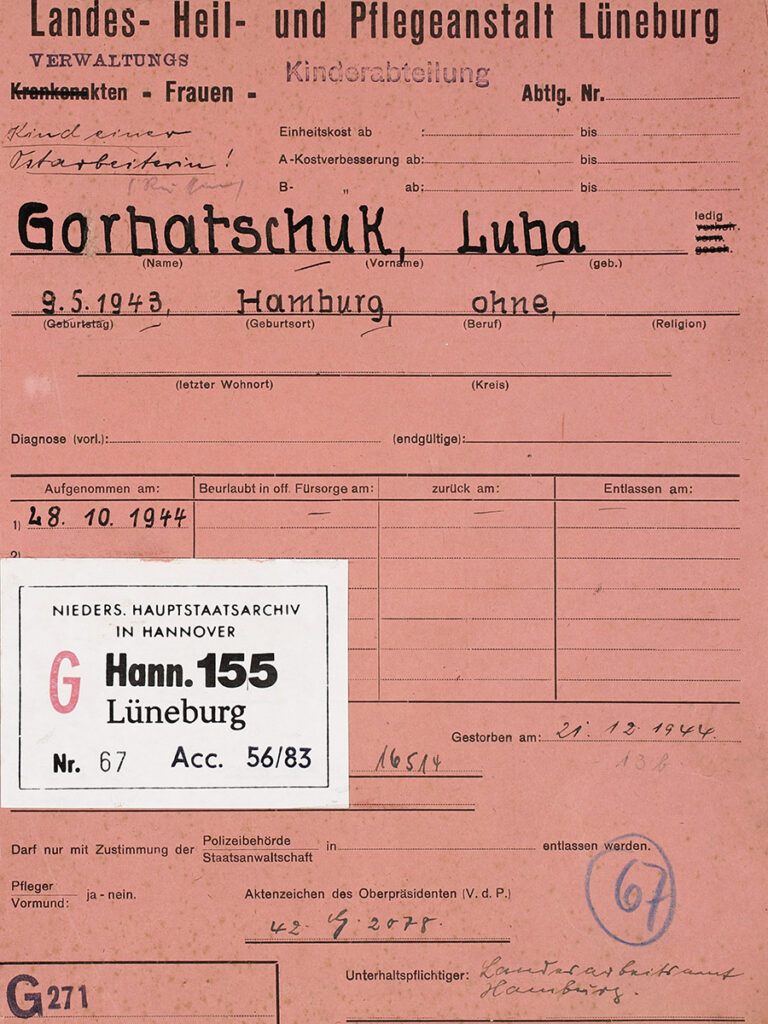

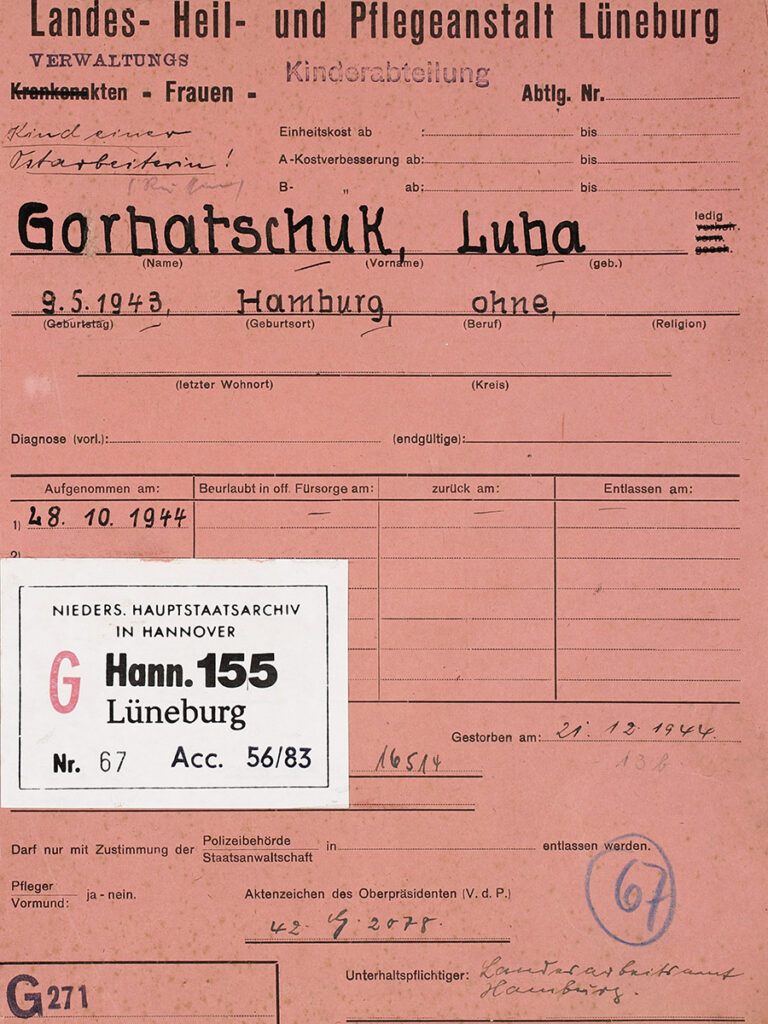

Deckel der Krankenakte von Luba Gorbatschuk, 1944.

NLA Hannover Hann. 155 Lüneburg Acc. 56/83 Nr. 67.

Die Kinder von Zwangsarbeiterinnen überlebten in der Regel nur wenige Wochen, weil die Übernahme der Pflegekosten nicht gesichert war. Dabei spielte es keine Rolle, ob sie tatsächlich erkrankt oder entwicklungsverzögert waren. Luba Gorbatschuk (1943 – 1944) kam in die »Kinderfachabteilung«, weil ihre Mutter aus dem Lager weggelaufen war und die Lagerleitung sie loswerden wollte. Luba hatte keinerlei Auffälligkeiten, außer dass sie gerade ihre ersten Zähne bekam.

Man behandelt nicht alle Kinder gleich

in der Kinder-Fachabteilung.

Die Kinder von Zwangs-Arbeitern behandelt man besonders schlecht.

Sie werden nach kurzer Zeit ermordet.

Auch gesunde Kinder werden ermordet.

Man ermordet sie, weil sie keine Deutschen sind.

Luba Gorbatschuk ist so ein Kind.

Ihre Mutter läuft aus einem Arbeits-Lager weg.

Die Lager-Leitung entscheidet:

Die Mutter ist weg.

Dann muss das Kind auch weg.

Luba kommt in die Kinder-Fachabteilung.

Dort wird sie nach 7 Wochen ermordet.

Die niederländischen Eltern von Benni Hiemstra waren Nationalsozialisten. Im August 1944 flüchteten sie ins Reich. Sie hofften, so den Alliierten zu entkommen. Benni war sieben Jahre alt, als er im Flüchtlingslager in der Schule in Amelinghausen gemeldet und dann in die »Kinderfachabteilung« eingewiesen wurde. Er starb innerhalb von nur drei Wochen.

Benni Hiemstra ist ein Flüchtlings-Kind.

Er flüchtet mit seinen Eltern aus den Niederlanden

nach Deutschland.

Die Eltern haben Angst vor den Engländern.

Denn die Eltern sind niederländische Nazis.

Sie wollen Rettung in Deutschland.

Sie kommen in ein Flüchtlings-Lager.

Dort wird Benni gemeldet,

weil er eine Behinderung hat.

Er kommt in die Kinder-Fachabteilung.

Er wird nach 3 Wochen ermordet.

Benni Hiemstra, um 1938.

Privatbesitz Johan Huismann | Tine Ovinck-Huismann.

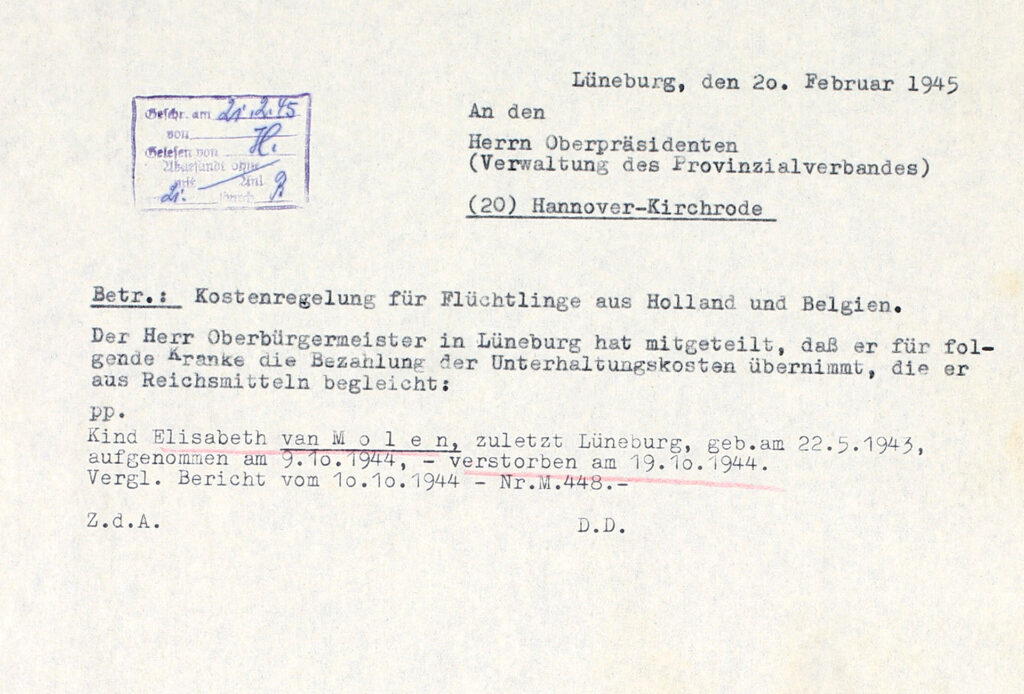

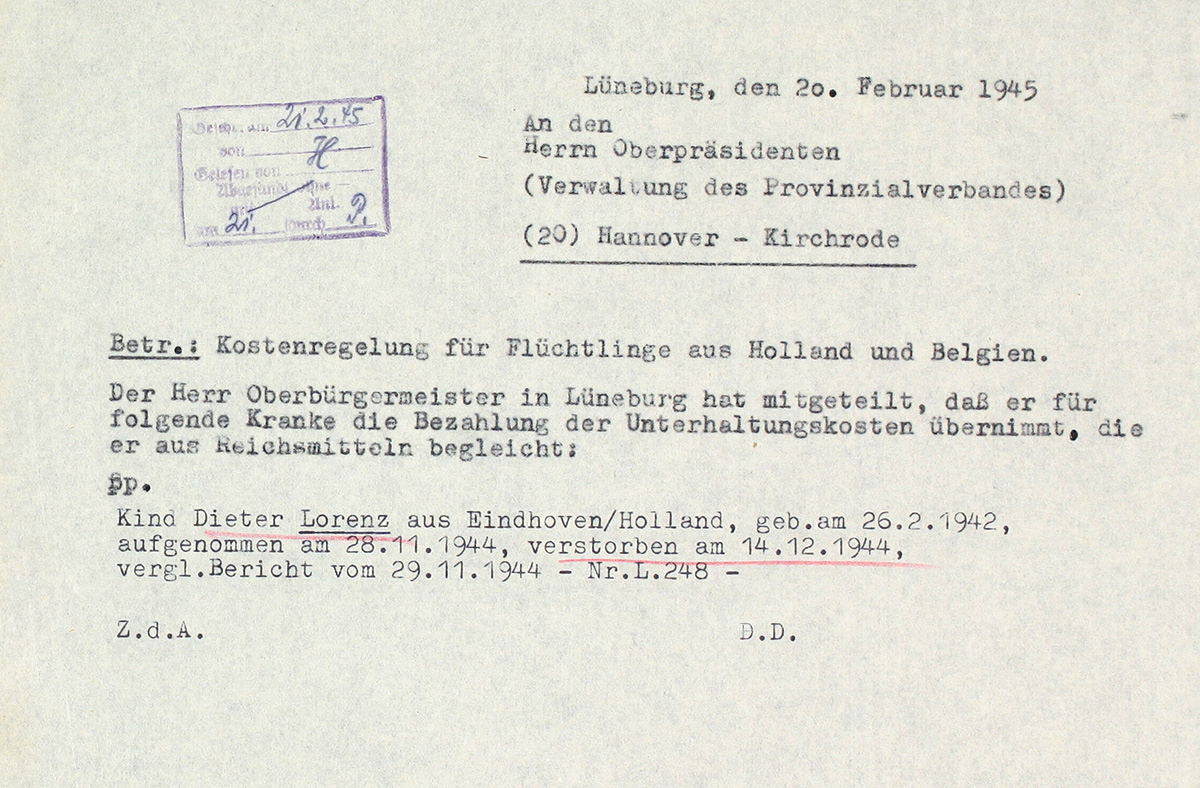

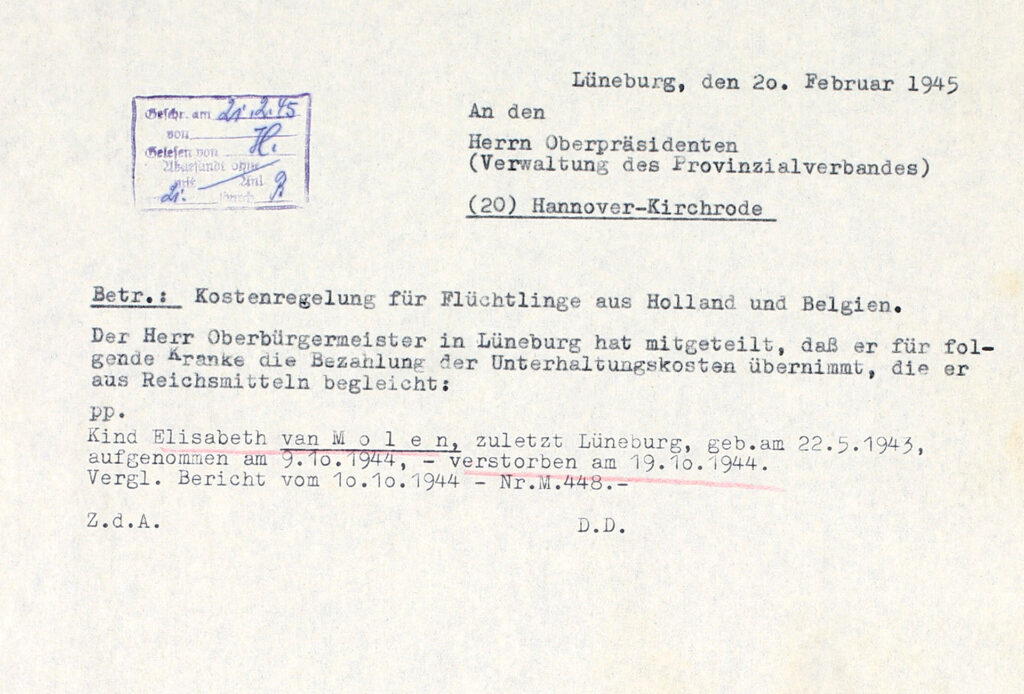

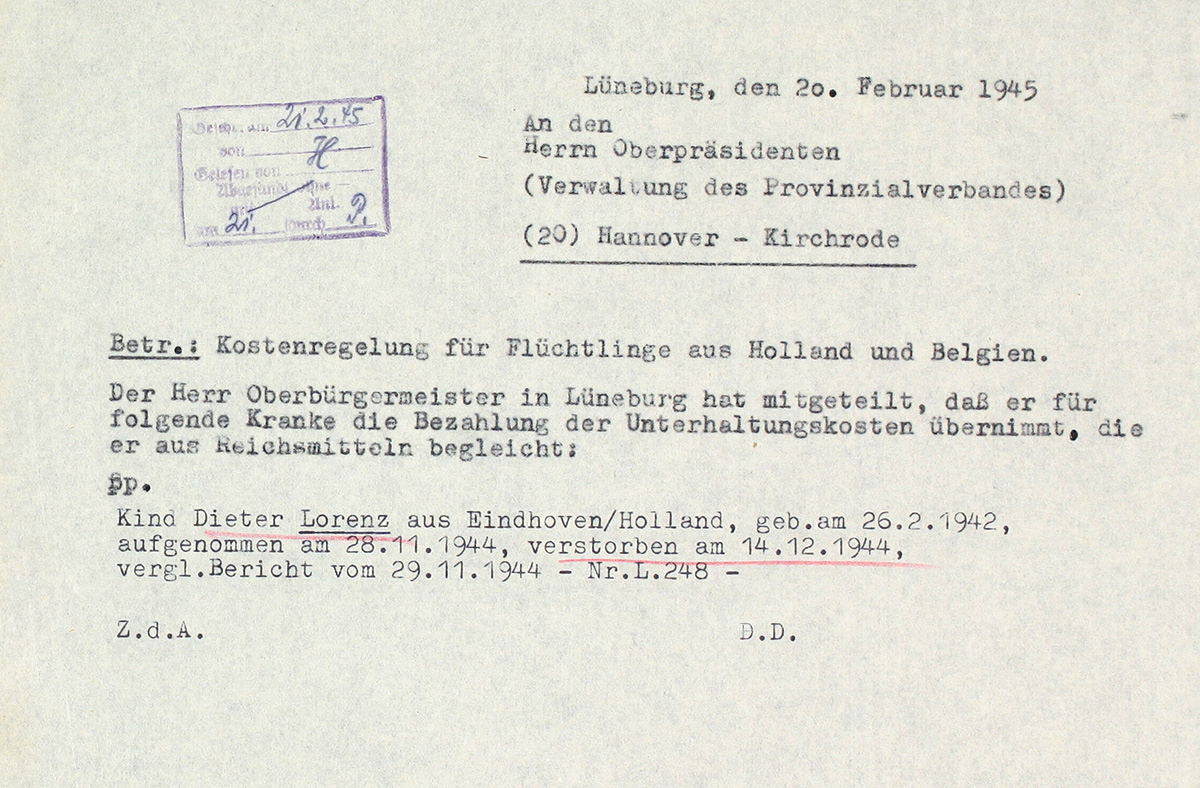

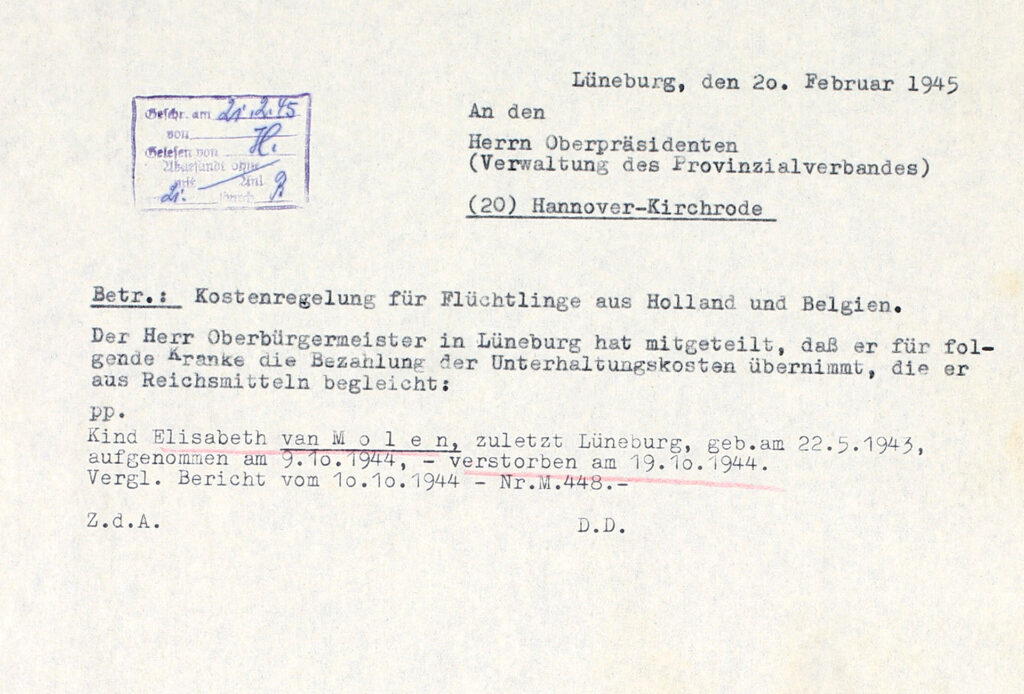

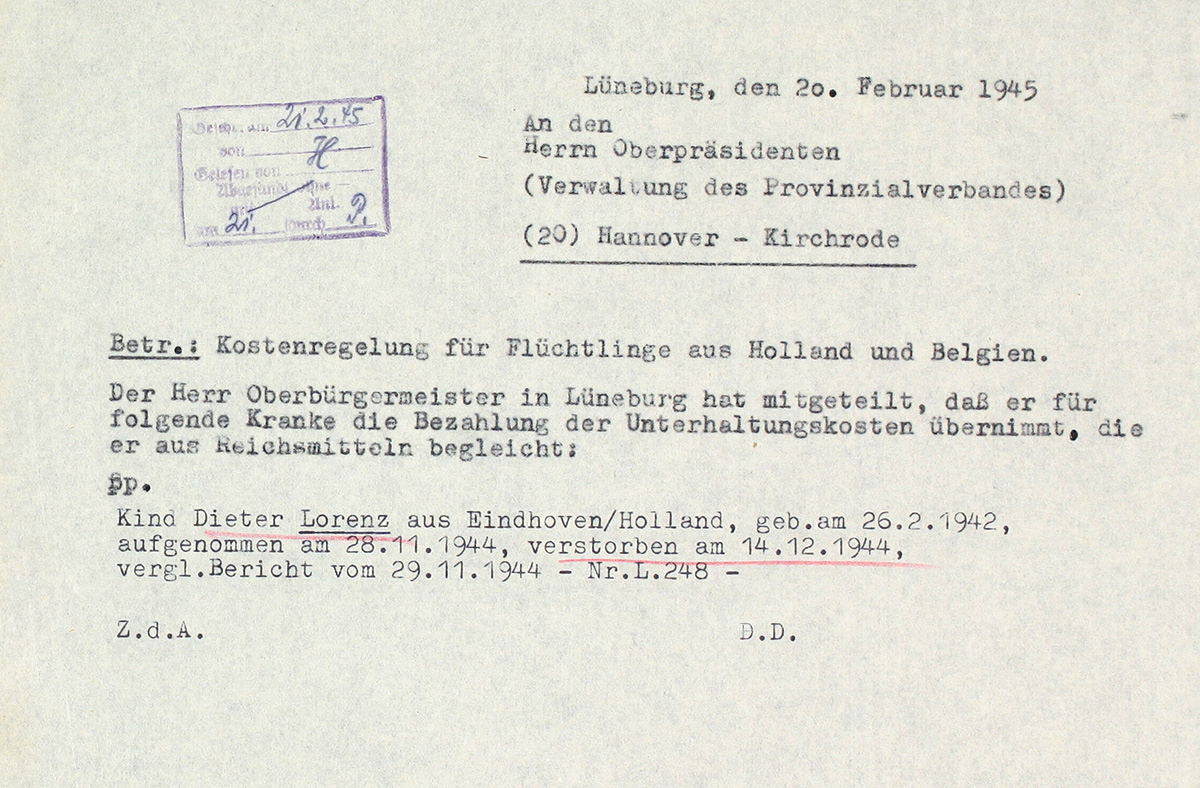

Brief der Stadt Lüneburg über die Kostenübernahme vom 20.2.1945.

NLA Hannover Hann. 155 Lüneburg Acc. 56/83 Nr. 136.

Elisabeth van Molen und Dieter Lorenz waren im Rahmen der NSV-Jugendhilfe-Westaktion ohne Eltern aus den Niederlanden ins Reich gebracht worden. Sie wurden nach nur wenigen Tagen ermordet. Bei ihnen war entscheidend, dass die Stadt Lüneburg zögerte, die Pflegekosten für die elternlosen Kinder zu übernehmen. Erst im Februar 1945 entschied die Stadt, die Kosten zu tragen. Da waren beide Kinder bereits tot.

Elisabeth van Molen und Dieter Lorenz kommen

aus den Niederlanden.

Beide Kinder kommen ohne Eltern nach Lüneburg.

Sie kommen in die Kinder-Fachabteilung.

Sie haben keine Kranken-Versicherung.

Keiner kennt die Eltern.

Keiner bezahlt für die Pflege.

Darum soll die Stadt Lüneburg

für die Kinder bezahlen.

Im Februar 1945 entscheidet die Stadt:

Wir bezahlen für die Pflege von Elisabeth van Molen und Dieter Lorenz.

Da sind die Kinder aber lange schon tot.

Sie wurden nach 2 und 3 Wochen ermordet,

weil sie zu viel Geld gekostet haben.

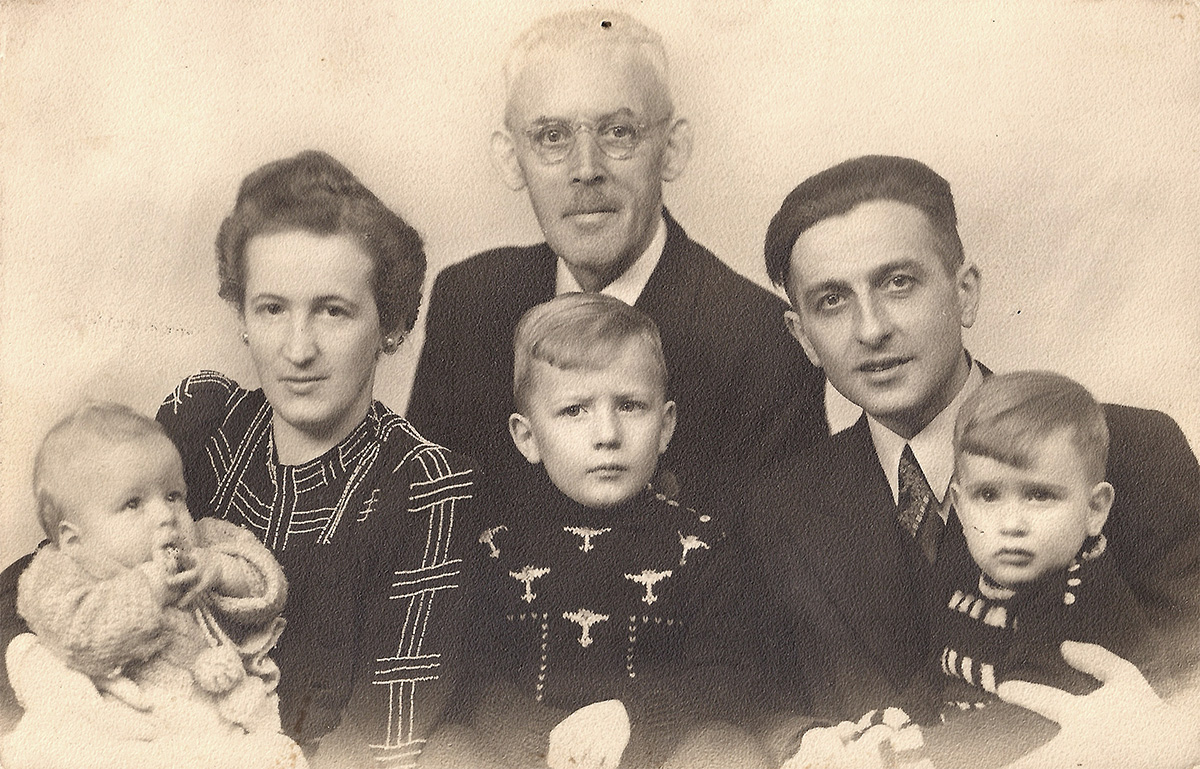

DIETER LORENZ (1942 – 1944)

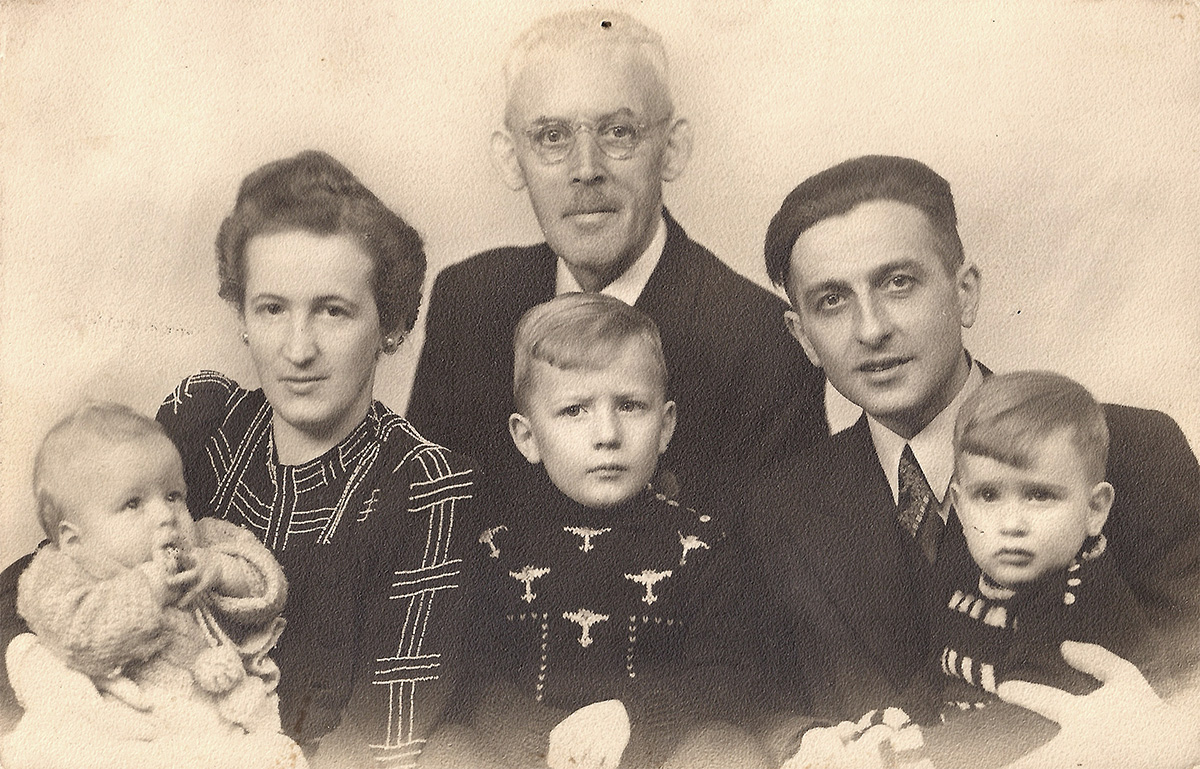

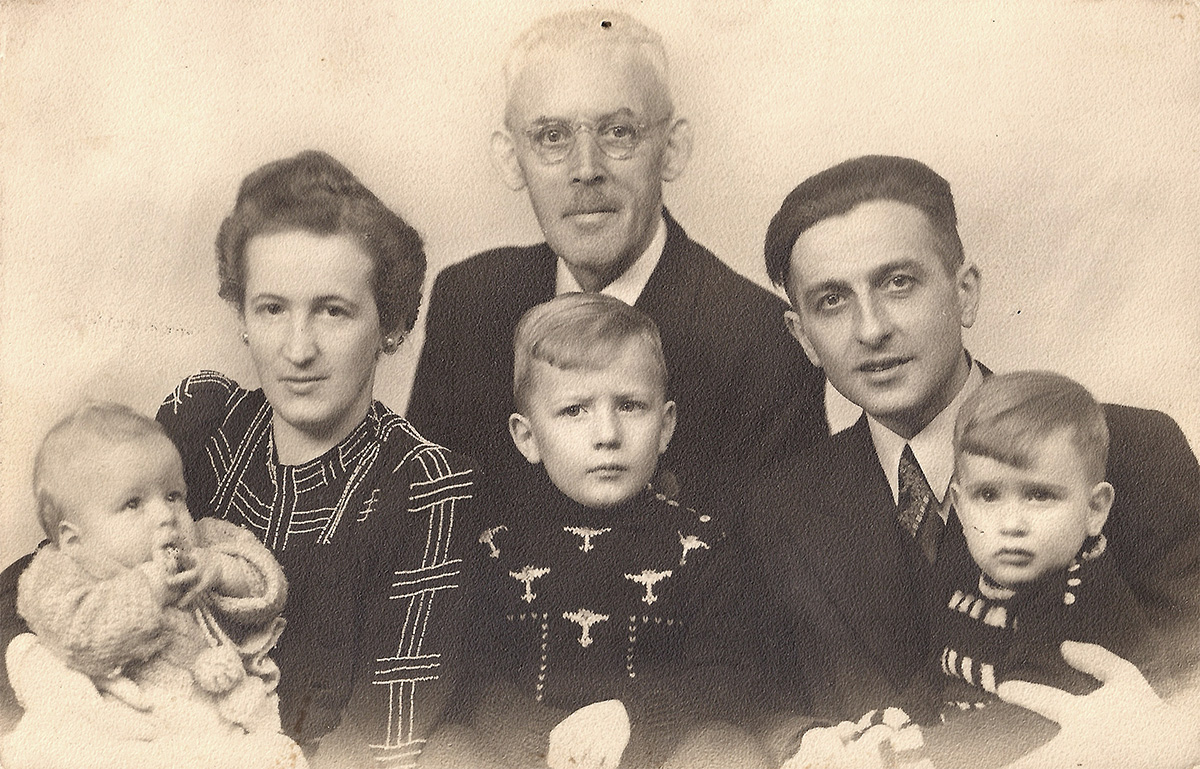

Familienfoto mit Dieter, Rolf und Helmut Lorenz (Vordergrund von links nach rechts), Aenne und Erich Lorenz dahinter und ganz hinten Heinrich Wilhelm Vennemann, Dieters Großvater, etwa Herbst 1942.

Privatbesitz Helmut Lorenz.

Dieter Lorenz wurde am 26. Februar 1942 in Eindhoven in den Niederlanden geboren. Sein Vater Erich war Kaufmann und stammte aus Schmölln in Thüringen. Seine Mutter Aenne (geborene Vennemann) war Niederländerin und Apothekerin. Sie heirateten 1934 und bekamen drei Söhne: Rolf, Helmut und Dieter.

DIETER LORENZ

Dieter Lorenz ist im Jahr 1942 geboren.

Seine Eltern haben ein Werkzeug-Geschäft.

Er hat 2 Brüder: Rolf und Helmut.

Sie leben in den Niederlanden.

Das ist ein Foto von Familie Lorenz

aus dem Jahr 1942.

Dieter ist da noch ein Baby.

Seine Mutter hat ihn auf dem Arm.

Rolf, Dieter und Helmut Lorenz, Eindhoven, Frühjahr 1943.

Privatbesitz Helmut Lorenz.

Weil Erich in die Wehrmacht eingezogen wurde und Aenne ab dann das Werkzeuggeschäft alleine führen musste, gab sie Dieter vorübergehend in ein Kinderheim. Anfang September 1944 wurde es geräumt, ohne die Eltern zu informieren. Die vergebliche Suche nach Dieter begann. Erich ließ sich zu Kommandos versetzen, wo Aenne in Erfahrung gebracht hatte, dass Dieter in der jeweiligen Gegend sein könnte.

Der Vater von Dieter Lorenz ist Deutscher.

Er muss als Soldat in den Zweiten Weltkrieg.

Dieters Mutter muss das Werkzeug-Geschäft

alleine führen.

Das schafft sie nicht mit Dieter.

Darum kommt Dieter in ein Kinderheim.

Da ist er 2 Jahre alt.

Wenig später muss das Kinderheim umziehen.

Dieter und ein anderes Mädchen kommen nach Lüneburg in ein anderes Heim.

Das ist ein Heim für Kinder-Flüchtlinge ohne Eltern.

Die Eltern wissen nicht,

dass ihre Kinder nun woanders sind.

Keiner sagt ihnen das.

Die Eltern fangen an, nach ihren Kindern zu suchen.

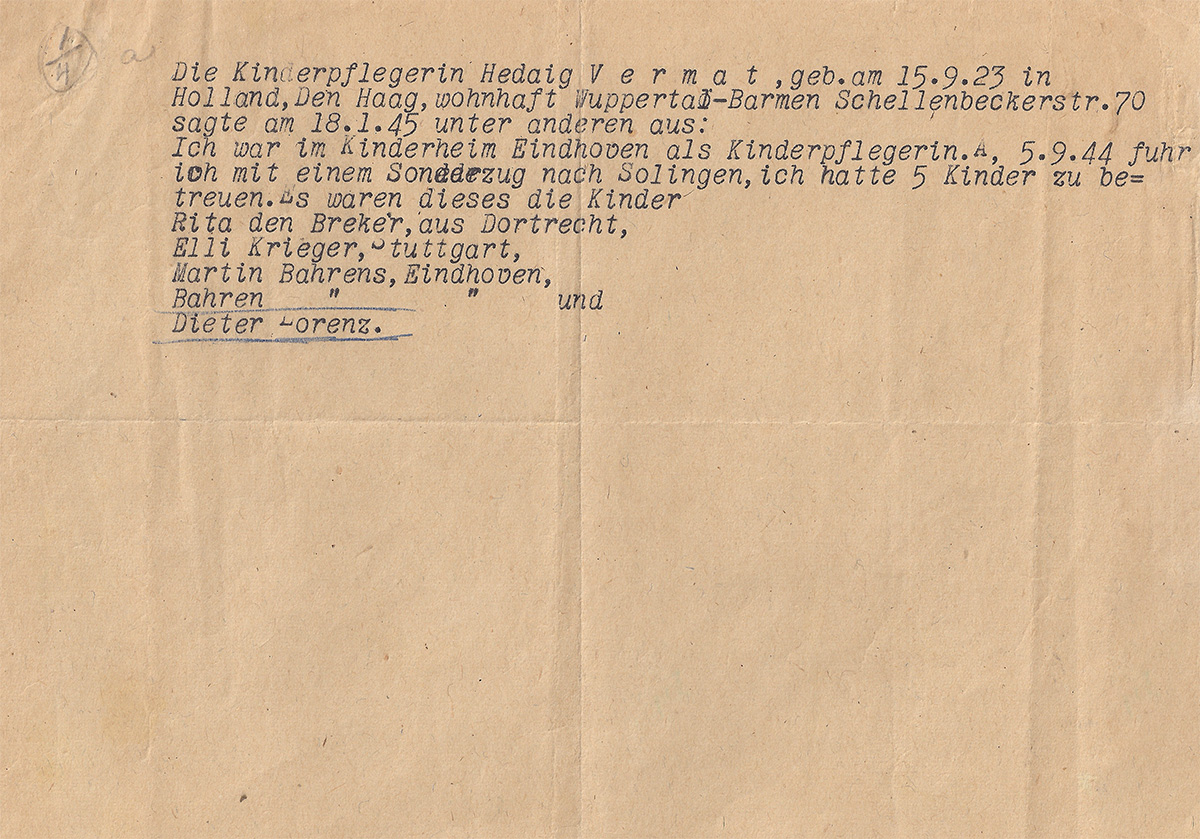

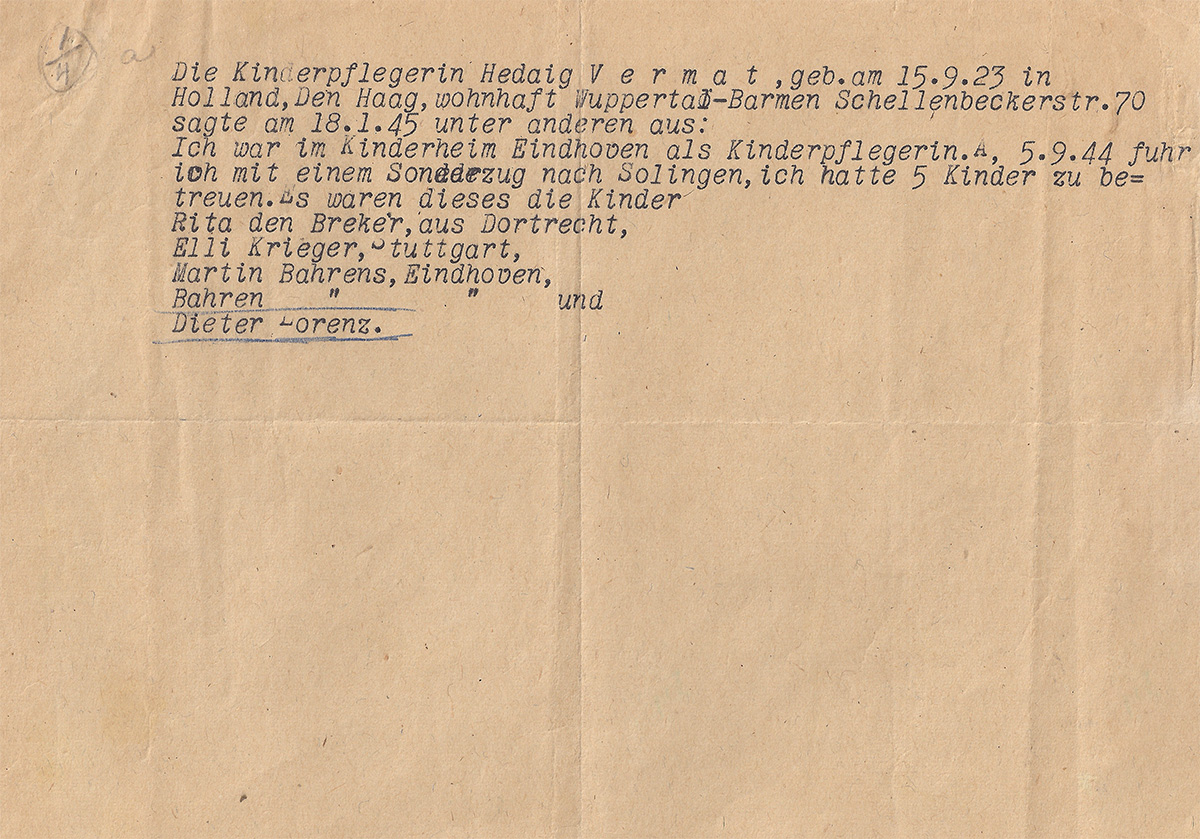

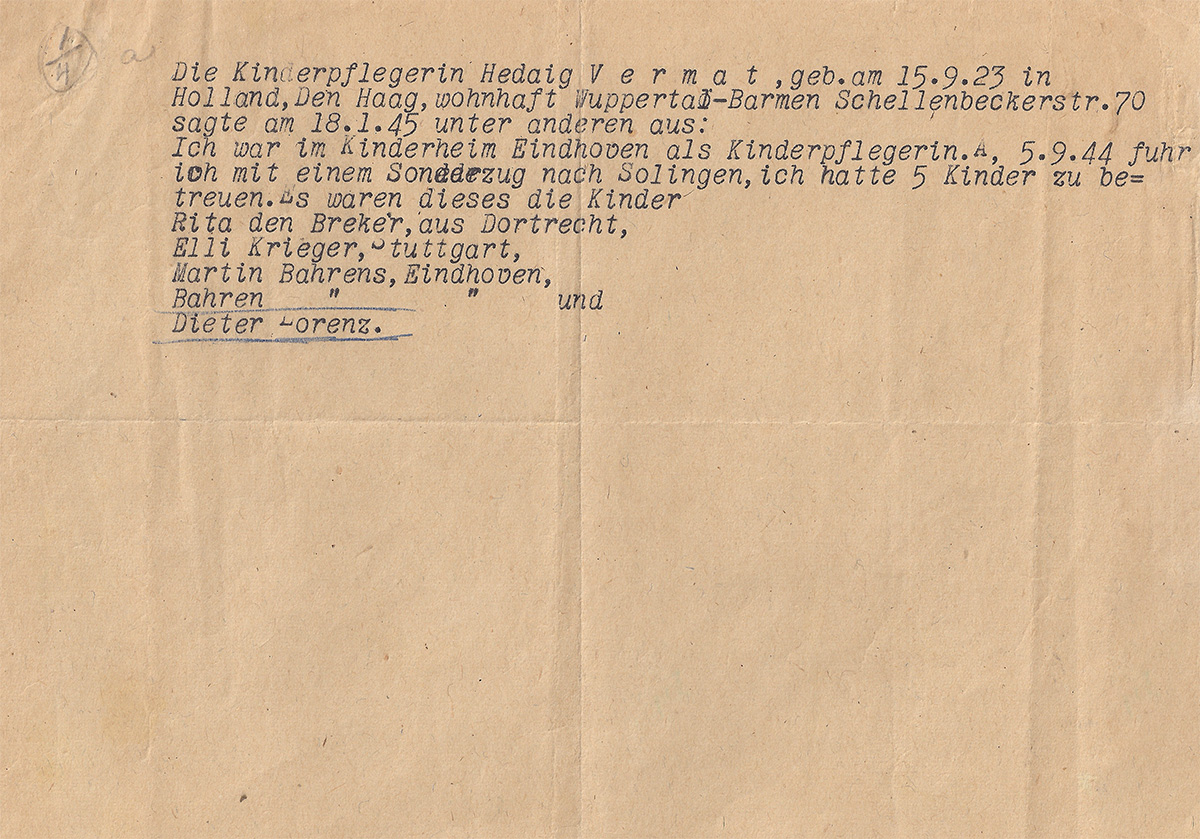

Vermerk, ohne Verfasser, ohne Datum, Dezember 1944.

Privatbesitz Helmut Lorenz.

Dieter kam über Hilden bei Solingen und Hannover nach Lüneburg in ein Auffanglager für elternlose Kinder. Dort wurde er selektiert und am 28. November 1944 in die »Kinderfachabteilung« Lüneburg eingewiesen. Er hatte eine Schachtel dabei, auf der sein Name »Lorenz« geschrieben war. Weil Rita den Breker, ein Mädchen aus dem Kinderheim, ihn als ihren »Bruder Dieter« bezeichnete, wurde er als »Dieter Lorenz« aufgenommen.

Dieter spricht nicht.

Keiner weiß, wie er heißt.

Nur das Mädchen Rita weiß es.

Sie sagt: Das ist Dieter.

Dieter hat eine Schachtel dabei.

Auf der Schachtel steht: Lorenz.

Darum wissen alle: Das ist Dieter Lorenz.

Die Frau vom Heim in Lüneburg sagt:

Dieter hat eine Behinderung.

Er muss in die Kinder-Fachabteilung.

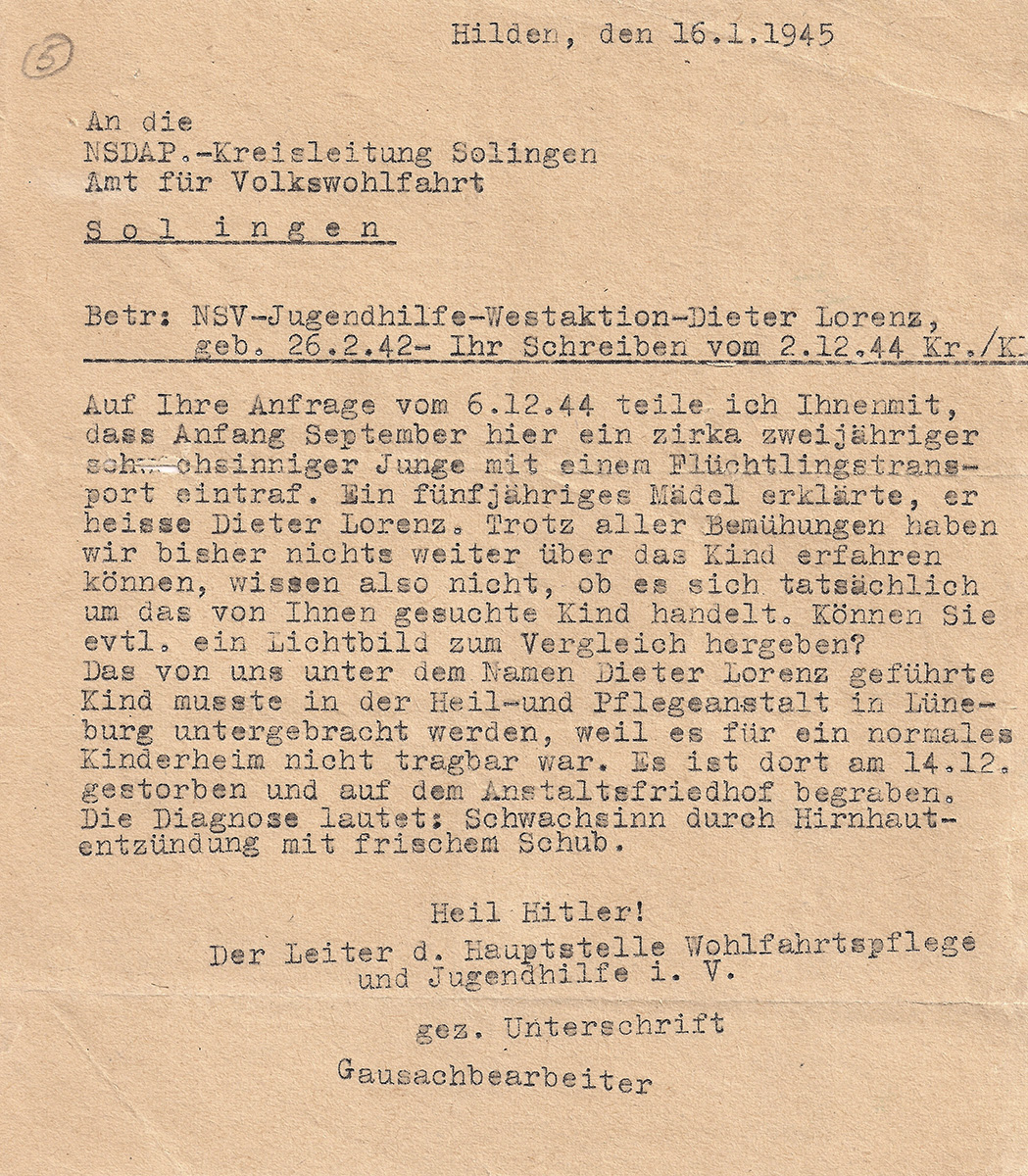

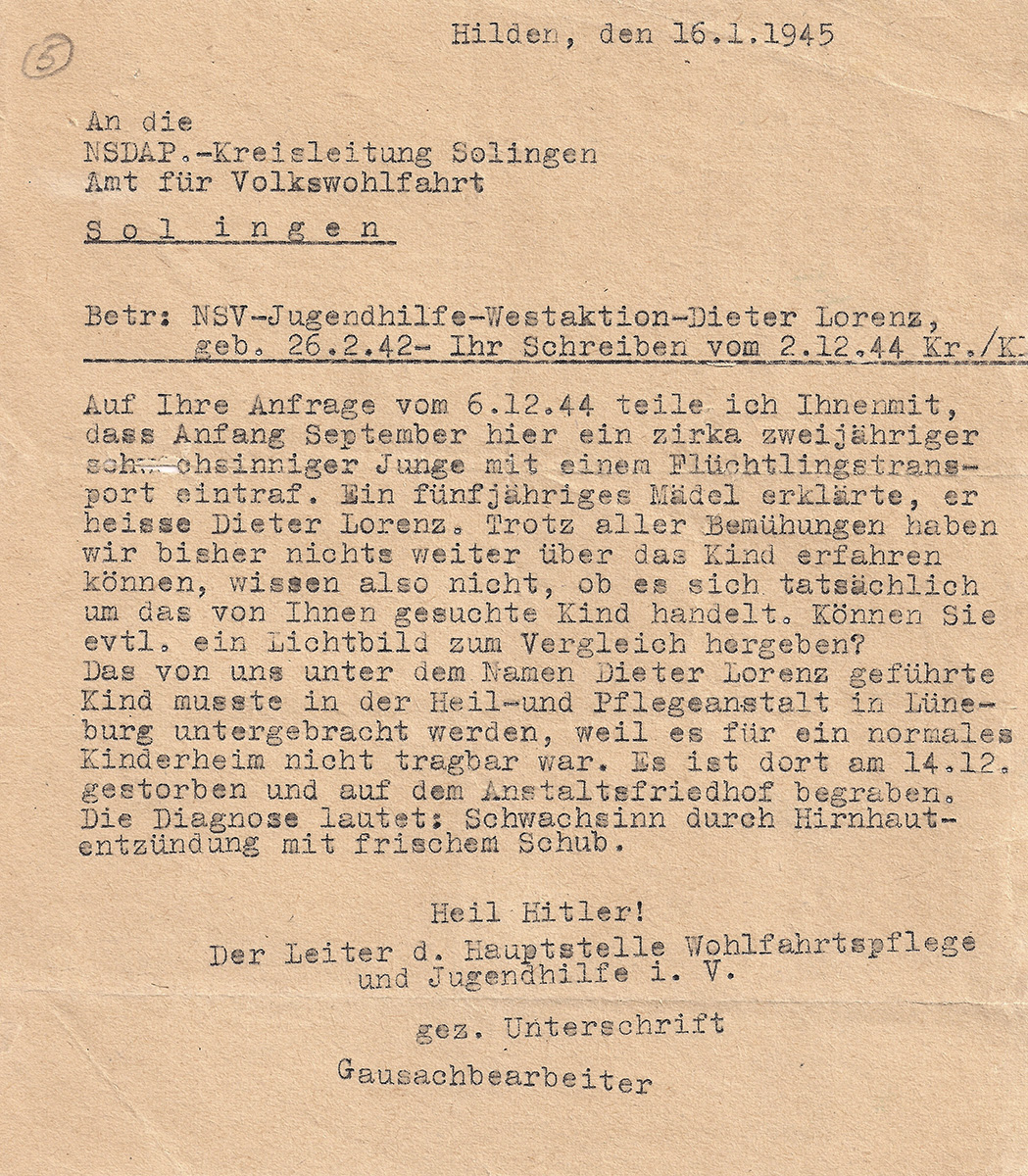

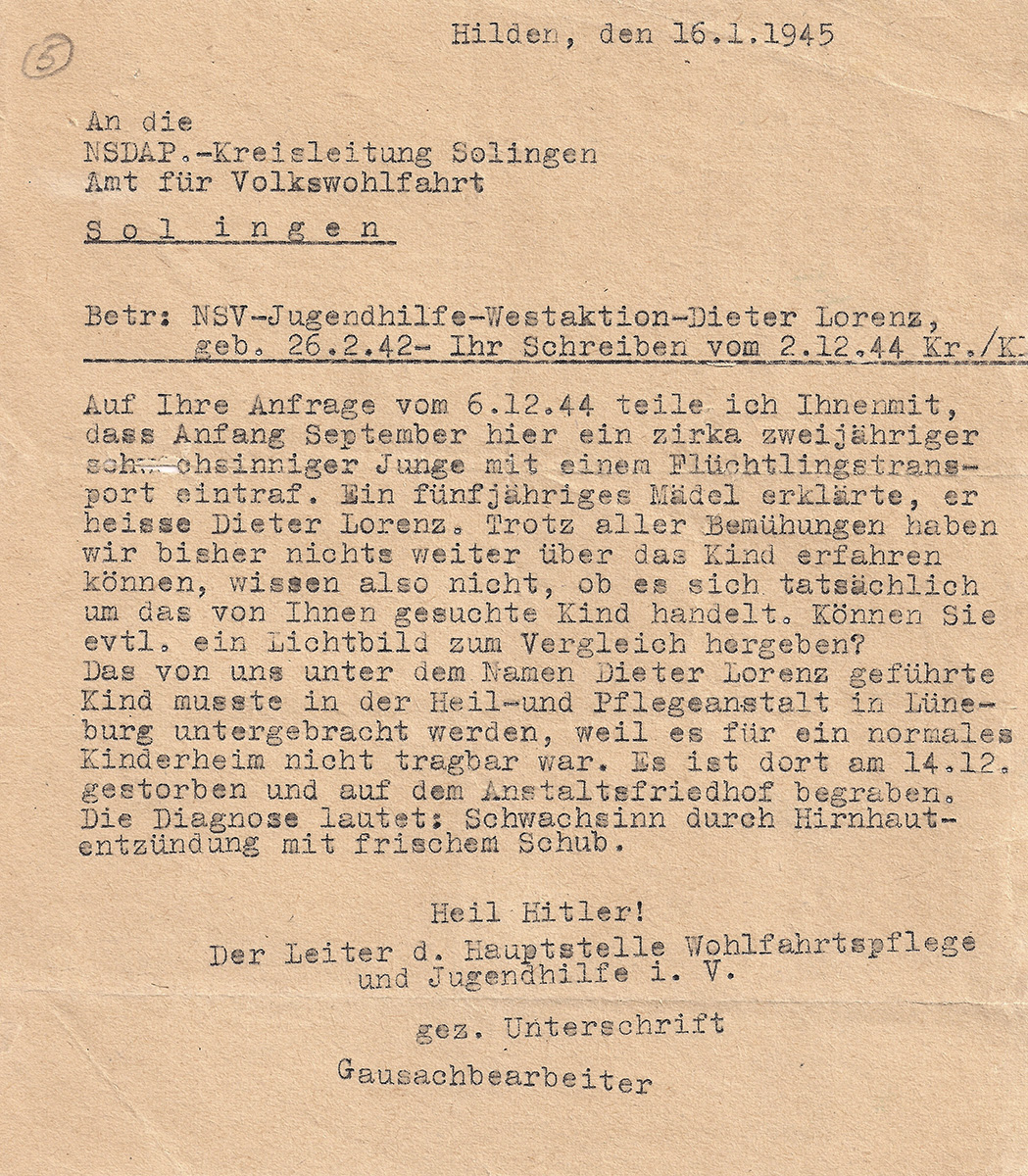

Schreiben der Wohlfahrtspflege und Jugendhilfe Hilden an die NSDAP-Kreisleitung Solingen, 16.1.1945.

Privatbesitz Helmut Lorenz.

Bei seiner Aufnahme wurde bei Dieter eine geistige Behinderung diagnostiziert. Weil angenommen wurde, er habe keine Eltern und die Stadt Lüneburg zunächst keine Kostenübernahme für das nicht-deutsche Kind zusicherte, wurde er 16 Tage nach seiner Aufnahme ermordet. Dieter starb am 14. Dezember 1944.

Die Anstalt in Lüneburg will Geld

für die Pflege von Dieter Lorenz.

Alle denken: Dieter hat keine Eltern.

Er hat keine Kranken-Versicherung.

Die Stadt Lüneburg überlegt,

ob sie für die Pflege von Dieter bezahlt.

Max Bräuner wartet nicht auf die Antwort

von der Stadt Lüneburg.

Nach 16 Tagen wird Dieter ermordet.

Damit er kein Geld mehr kostet.

Schreiben vom 20.2.1945.

NLA Hannover Hann. 155 Lüneburg Acc. 56/83 Nr. 311.

Die Stadt Lüneburg erklärt sich am 20. Februar 1945 bereit, die Kosten für Dieters Aufenthalt zu übernehmen. Da ist er schon seit über zwei Monaten tot.

Ende Februar 1945 schreibt die Stadt Lüneburg:

Wir bezahlen für Dieter Lorenz.

Aber da ist Dieter schon 9 Wochen tot.

Dieters Eltern erfuhren erst im Januar 1945 von seinem Tod. Die Brüder erfuhren nie, dass Dieter eine Behinderung hatte. Man erzählte ihnen, er sei mit einem Bus des Roten Kreuzes verlorengegangen. Daraufhin suchte Helmut Lorenz seinen kleinen Bruder fast weitere 70 Jahre. 2014 konnte Dieters Schicksal aufgeklärt werden.

Die Eltern von Dieter Lorenz bekommen

die Todes-Nachricht im Januar 1945.

Aber sie wollen es nicht glauben.

Sie sagen:

Vielleicht lebt Dieter noch.

Helmut Lorenz sucht seinen Bruder Dieter

70 Jahre lang.

Im Jahr 2015 findet er die Wahrheit raus.

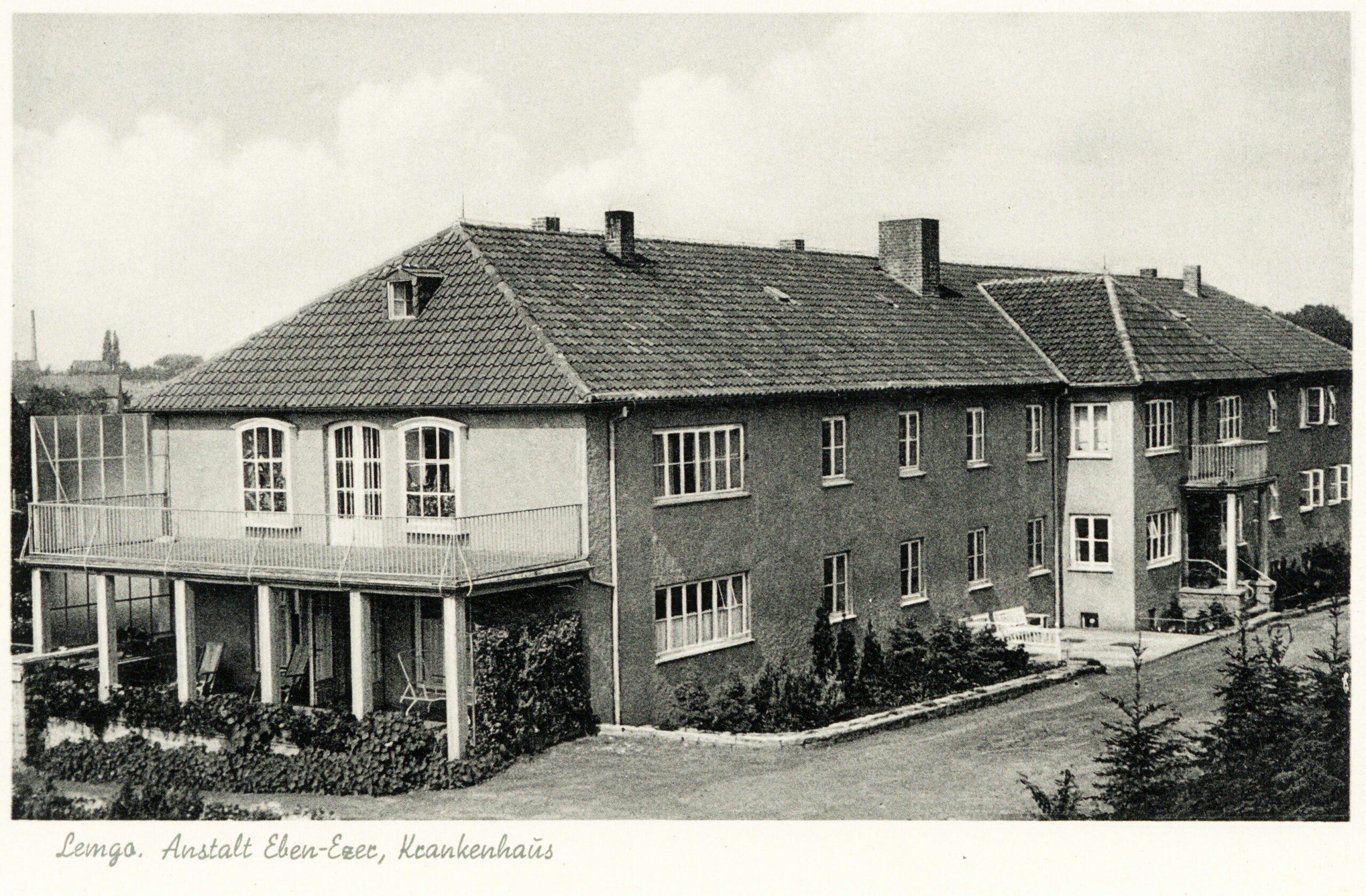

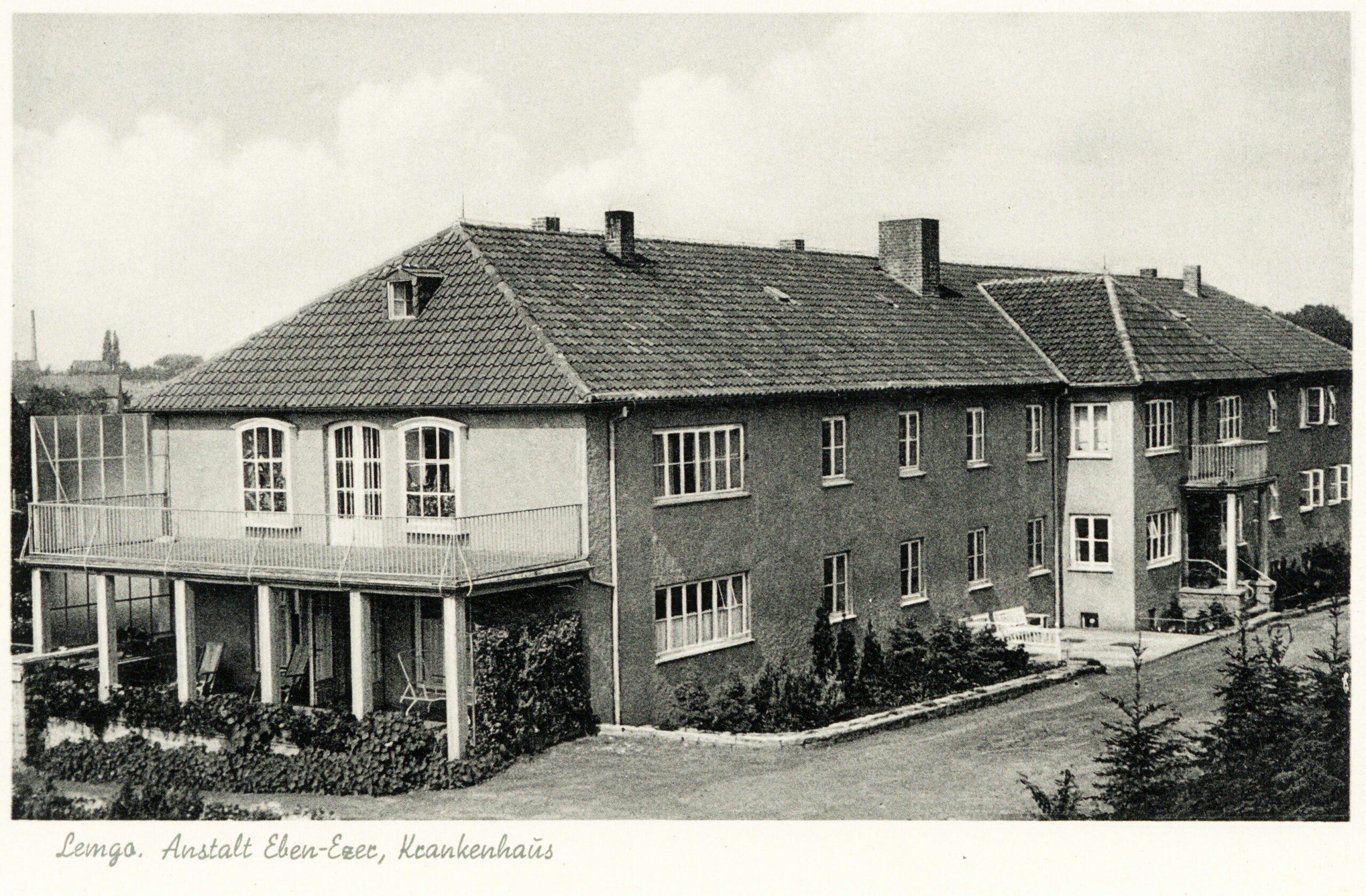

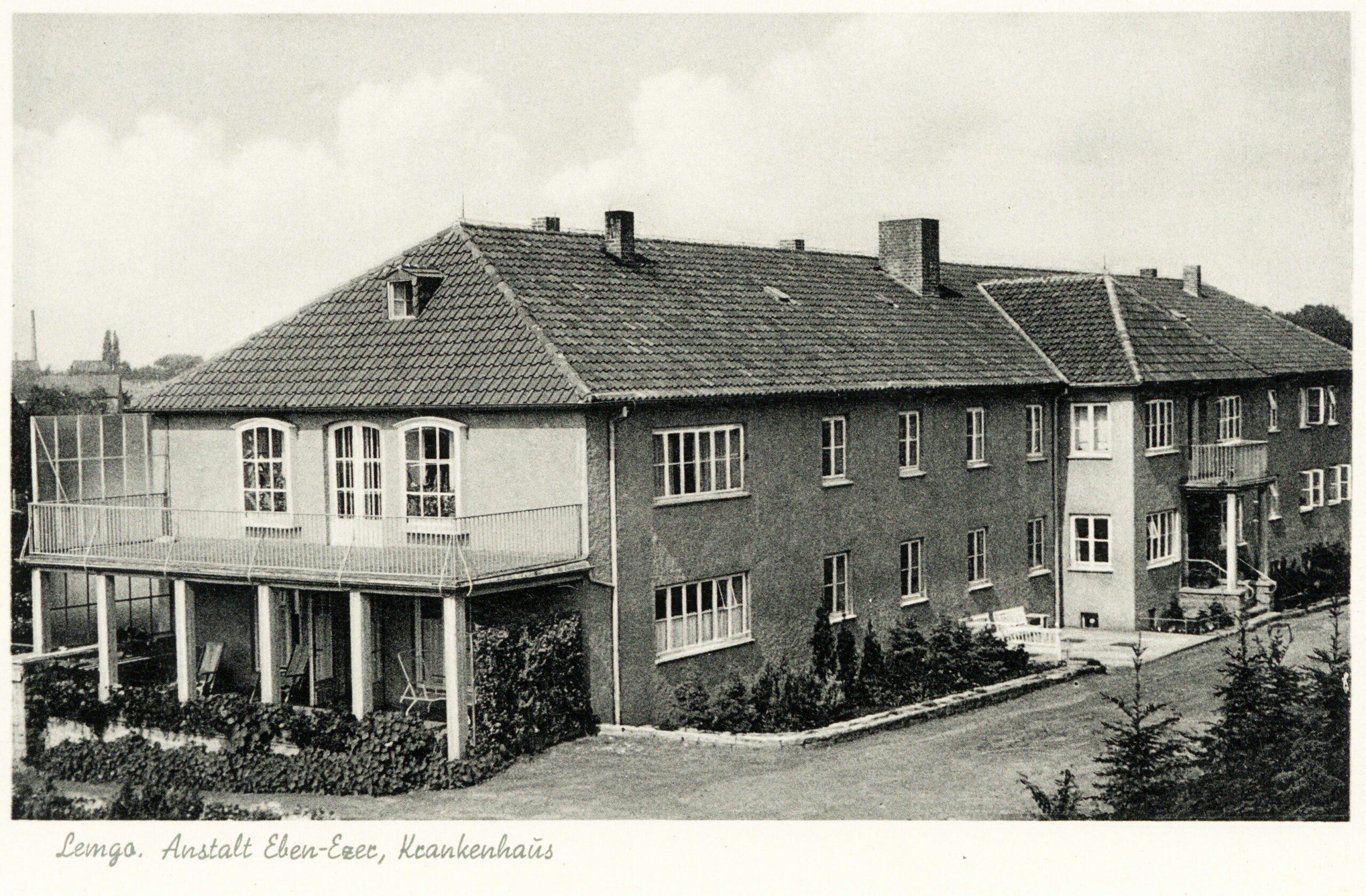

Postkarte der Anstalt Eben-Ezer in Lemgo, nach 1945.

NArEGL 99.

Etwa 40 Prozent der eingewiesenen Kinder und Jugendlichen überlebten die »Kinderfachabteilung« Lüneburg. 103 Kinder (39 Mädchen, 64 Jungen) wurden für einen »Beschulungsversuch« nach Lemgo (Eben-Ezer) verlegt. Dort gab es eine Hilfsschule. Elf von ihnen wurden zurücküberwiesen, Gertrud Krebs und Kurt Bock starben dadurch. Auch die Stiftung Eben-Ezer war kein sicherer Ort. Es sind zwölf weitere Kinder und Jugendliche bekannt, die die Stiftung von sich aus in die »Kinderfachabteilung« einwies.

Wenige Kinder überleben

in der Kinder-Fachabteilung in Lüneburg.

Nur etwa eins von 3 Kindern überlebt.

103 Kinder verlassen die Kinder-Fachabteilung.

Zwischen 1941 und 1945.

Sie kommen nach Lemgo in die Stiftung Eben-Ezer.

Dort gibt es eine Hilfsschule.

Sie sollen dort zur Schule gehen.

11 Kinder schaffen die Hilfsschule nicht.

Sie kommen zurück in die Kinder-Fachabteilung nach Lüneburg.

2 Kinder sterben dann in der Kinder-Fachabteilung.

In Eben-Ezer sind die Kinder auch nicht sicher.

12 Kinder aus Eben-Ezer kommen auch

in die Kinder-Fachabteilung.

Weil sie ihren Namen und ihr Alter kannte, sich benahm und interessiert zeigte, überwies Willi Baumert Gertrud Krebs bereits sechs Wochen nach ihrer Aufnahme nach Eben-Ezer. Ein Jahr später kam sie als »nicht schulfähig« zurück. Handschriftlich notierte Max Bräuner im November 1944, dass es keine Besuche und Anfragen gab. Dies war auch deshalb unwahrscheinlich, weil sie zu Anfang aus einem Kinderheim aus Amt Neuhaus eingewiesen worden war. Drei Monate nach diesem Eintrag lebte sie nicht mehr.

Gertrud Krebs ist in der Kinder-Fachabteilung

in Lüneburg.

Sie weiß ihren Namen.

Sie weiß ihr Alter.

Sie fragt viel.

Sie versteht viel.

Darum sagt der Arzt Willi Baumert:

Gertrud soll auf eine Hilfsschule.

Sie soll nach Eben-Ezer.

Das passiert dann auch.

Ein Jahr später kommt Gertrud zurück

in die Kinder-Fachabteilung.

Die Lehrer sagen:

Sie ist schlecht in der Schule.

Sie ist zu dumm für eine Hilfsschule.

Max Bräuner schreibt:

Keiner besucht Gertrud.

Keiner fragt nach ihr.

Er denkt:

Es stört keinen, wenn Gertrud stirbt.

3 Monate später ist Gertrud tot.

Auszug aus der Krankengeschichte von Gertrud Krebs.

NLA Hannover Hann. 155 Lüneburg Acc. 56/83 Nr. 110.

RESEARCH AND THE LAST YEARS OF THE WAR

In 1948, Willi Baumert admitted that he had travelled to Berlin to the »Führer’s Chancellery« to find out the aims and purpose of the »children’s department«. Hans Hefelmann told him that research was being carried out on children and young people to determine the causes of their impairments. The results were to contribute to the prevention of diseases and disabilities. In addition, the »Law for the Prevention of Hereditary Diseases« was to be improved.

Excerpt from the transcript of the autopsy of 338 children and adolescents, in this case Friedrich Daps, dated 23 March 1942.

Private collection, Institute for the History and Ethics of Medicine, Hamburg.

On the one hand, the research was carried out through observation and intelligence testing. On the other hand, the children and adolescents were physically examined. For this purpose, blood and cerebrospinal fluid were taken and organs were removed from the children’s bodies. A room was set up in the basement of House 25 where the corpses could be opened. Willi Baumert carried out 338 such operations and removed the brains. He examined them and wrote everything down.

He gave many organs to the University Medical Centre Hamburg-Eppendorf (around 37 donations are documented). Wafer-thin sectional preparations were made there. When Willi Baumert had to return to the war effort in August 1944, Max Bräuner took over the removal and examination of the brains.

Microscope slide with section by Marianne Begemann, University Medical Centre Hamburg-Eppendorf (UKE), 1942.

Institute for the History and Ethics of Medicine, Hamburg.

These are the names of the children and adolescents whose brains and other organs were donated to the University Medical Centre Hamburg-Eppendorf (UKE):

Anita, Helga and Helmut Volkmer, around 1937.

Private property Marlene Volkmer.

The first brain to be sent to Hamburg for research was that of Helga Volkmer. She was murdered on 30 November 1941 and was one of the first victims of the Lüneburg »child euthanasia« programme. She is proof that the Lüneburg »specialised children’s department« did not begin its work in 1942 with the first »Reichsausschuss« children, but with the arrival of the children from the Rotenburg institutions of the Inner Mission.

Hans Jacob, after 1945.

Lawrence Zeidman: Brain Science under the Swastika. Ethical Violations, Resistance, and Victimization of Neuroscientists in Nazi Europe, Oxford 2020.

At the UKE, brain researcher Hans Jacob used organs from Lüneburg for his research. He worked for the »Reichsausschuss« (Reich Committee). Many brain researchers collaborated with »killing« and research institutions. Hans Heinze (Görden) and Julius Hallervorden (Berlin) were even present at the murders of patients in order to begin their examinations and start their collections immediately after death.

Willi Baumert was particularly interested in children whom he suspected of having Hurler syndrome. This is also the reason why there were so many brain sections taken from Heinrich Herold from Duingen.

Heinrich Herold, Helmut Sievers and Irmgard Herold (from left to right) in front of their family home in Duingen, 1938.

Privately owned by Holger Sievers.

Privately owned by the Schäfer family.

This is the last photo of Heinz Schäfer, taken in autumn 1941. A few weeks later, he was admitted to the children’s ward in Lüneburg and died shortly afterwards. His parents couldn’t believe it. His father travelled to Lüneburg and had the coffin opened to make sure. Heinz’s head was bandaged. The family could not explain this, as Heinz had officially died of »diphtheria and catarrhal pneumonia«’.

The families were not told that the brains had been removed. Heinz Schäfer’s death was a constant source of speculation within the family. In 2012, brain specimens stored at the UKE were identified as belonging to him. The family was informed of his true fate for the first time. After many decades, they finally received an answer to the question of why Heinz’s head had been bandaged. Willi Baumert and Hans Jacob had used his brain for their research.

Transcript by Willi Baumert on the examination of Heinz Schäfer’s brain, 1942.

First page of Hans Jacob’s notes on the examination of Heinz Schäfer’s brain, University Medical Centre Hamburg-Eppendorf, 1942.

Institute for the History and Ethics of Medicine Hamburg.

These extracts contain shocking images. Showing them is controversialThese extracts contain shocking images. Showing them is controversial.

Decide for yourself whether you want to open the pull-out.

Tub for opening corpses, ca. 1941.

ArEGL.

In October 2023, this tub was found in the basement of House 25, the location of the former »children’s ward«. It is highly likely that this is an autopsy tub. Traces in the basement rooms of House 25 indicate that the bodies of the children and adolescents were not taken across the institution grounds to the official autopsy room at the time, but were opened on site in House 25.

These are disturbing images. They show a boy and a girl in great distress and miserable conditions. The identities of the two children are unknown. Willi Baumert used the photos for his »research«. They are degrading, horrific images. They show, without mercy, the brutality and inhumanity that the children had to endure in the »children’s ward« in Lüneburg. That is the only reason we are showing them.

Five photographs of children, taken in the »children’s ward« in Lüneburg, 1942/1943. Photographer Ruth Supper.

ArEGL FB 2/34.

Inge Roxin, »Children’s ward« Lüneburg 1943.

Private property of Sigrid Roxin.

The children were made ill with pathogens in order to research the effectiveness of the unlicensed drug »Eubasin«. Mariechen Petersen was only not ill during the time when her mother was able to visit her. »Eubasin« worked on her neighbour Inge Roxin. She recovered before Willi Baumert murdered her.

This photograph was taken in the »children’s ward«. The image shows that Inge Roxin was in poor health. She was subjected to human experiments. The image is problematic. But not showing it would downplay the actual misery. There is no photograph of Mariechen Petersen.

It is uncertain whether trials with vaccines against tuberculosis, scarlet fever or other diseases were also conducted in the Lüneburg »paediatric ward«. In contrast to the treatment of adult patients, especially in the so-called ‘foreigners‘ collection centre’, there is no evidence of this for children and adolescents to date.

Many employees from the nursing staff, but also from the administration and non-nursing areas of the Lüneburg sanatorium and nursing home were involved in the research in the »children’s ward«. None of them did anything to prevent the deaths of the children or to improve their situation. They can therefore be regarded as accomplices.

Letter to Dresdner Bank with instructions regarding the payment of »special allowances« dated 15 December 1943.

BArch NS 51/227.

Those involved in the murders in the »children’s ward« and their accomplices received »special allowances« as a reward. This list shows that the Görden »children’s ward« received the highest amount in »special allowances« because there were a particularly large number of participants and accomplices in the »child euthanasia« programme there in 1943. The list does not include all the ‘children’s wards’ where children and young people were murdered that year.

Letter from Max Bräuner to the »Reich Committee« dated 28 November 1943.

BArch NS 51/227.

The employees of the Lüneburg »children’s ward« did not receive any ‘special allowances’ in 1941. In 1942, nurses Wilhelmine Wolf and Dora Vollbrecht were each paid an extra 30 Reichsmarks. For 1943, Max Bräuner recommended nurses Wilhelmine Wolf and Hertha Walther as well as his senior physician Willi Baumert for additional payments. As a physician, Baumert was rewarded with 100 Reichsmarks, meaning that Lüneburg received a total of 160 Reichsmarks from the »Reich Committee« in 1943.

All correspondence between the Reich Committee and the institution, the expert reports, the entries made during visits, and the transcripts of the autopsies were written by the secretary Karola Bierwisch (née Kleim). She was not only the secretary to the medical director Max Bräuner, but also his assistant in his lethal research. For this reason, she also received a ‘special allowance’ from the »Reich Committee« for the year 1944.

Letter from Max Bräuner to the »Reich Committee« dated 7 December 1944.

BArch NS 51/227.

Letter from the »Reich Committee« to the Kalmenhof mental hospital dated 27 September 1944.

BArch NS 51/227.

In 1944, individual nurses received a monthly allowance of 35 Reichsmarks for their participation in the killing of patients. The nurses in Lüneburg also received such an allowance. It was intended to strengthen loyalty and increase motivation.

Letter from the Großschweidnitz mental hospital to the Reich Committee dated 4 October 1944.

BArch NS 51/227.

Those who had rendered outstanding services in the so-called »Reich Committee work« received a medal. They were awarded the »Medal of Honour for German Social Welfare«. The murders they had committed were thus »valued«.

Nurses August Gebhardt and Ernst Meier assisted with the autopsies in the »Children’s ward« in Lüneburg. Gebhardt had been a nurse since 1912 and was responsible for opening and resealing the bodies from 1938 onwards. Although the mother of »T4« victim Paul Hausen told him that she believed her son had been murdered, Gebhardt had no idea that the many children’s bodies he had to deal with were also victims of euthanasia.

Excerpt from the transcript of the interrogation of August Gebhardt on 1 November 1947.

NLA Hannover Nds. 721 Lüneburg Acc. 8/98 No. 3.

Overview of nursing staff in the »Children’s ward« dated 4 October 1947.

NLA Hanover Nds. 721 Lüneburg Acc. 8/98 No. 3.

The children and young people were looked after and cared for by a total of 21 nursing staff working in three shifts. In addition to the three nurses Wilhelmine Wolf (head nurse), Ingeborg Weber (who took her own life and is therefore not on the list) and Dora Vollbrecht, there were many other nurses who neglected the children and young people, provided them with inadequate care and stood by and watched them die.

»At the institution, I have seven nurses working simultaneously for approximately 130 children. It is impossible to hire more staff due to the personnel difficulties caused by the war; one also wonders whether more responsibility can be taken on given the worthlessness of this human resource in the current wartime situation.«

Excerpt from a letter from Max Bräuner to the Wittmund State Health Office dated 17 October 1942.

NLA Hanover Hann. 155 Lüneburg Acc. 56/83 No. 145, p. 2.

There were 35 siblings from 15 families in the »Children’s ward« in Lüneburg. Up to four children from one family were admitted. Sometimes all of the children were taken away from their parents. Even after the war, many children did not return home. Of the siblings, only one saw his parents again. From 1945 onwards, the young people were handed over to youth welfare services. Many of the survivors remained residents of the institution until the 1970s.

ERIKA (1936–1944) AND MARGRET BUHLRICH (1941–1945)

Hans Buhlrich, 1936.

Erika Buhlrich, around 1937.

Margret Buhlrich, around summer 1944.

Private property of Friedrich Buhlrich.

The Buhlrich siblings from Bremen were sent to the Lüneburg »Children’s ward« in 1944. Their brother Hans (1932–1942) had already died in Kutzenberg (Bavaria) in 1942. He had been evacuated from the Gertrudenheim near Bremen after only a few days. The sisters were murdered about two years later so that their brains could be examined to see if there was a pathological predisposition and whether their mother should not have a fourth child. They had been considered a nuisance in their neighbours‘ air-raid shelter during the bombings. The mother was very interested in finding out why her son Hans had a lame arm and her two girls had developmental delays. In order to find out the cause, first Erika died, then Margret. After the parents learned that Erika must have had meningitis, but the origin of the other impairments remained unclear, the Buhlrichs decided not to have any more children. Instead, they adopted a child born to a German woman and a Polish forced labourer. Friedrich Buhlrich remained unaware of the existence of his three biological siblings until the death of his adoptive parents.

The children witnessed the murder and watched their siblings die. This was also the case with the Köhler twins. Herbert’s health deteriorated, and by January 1945, the 16-year-old weighed only 28.5 kg. He died on 22 March 1945. His twin brother Willi was with him. The loss hit him hard. Afterwards, his brother worked diligently, ensuring that there were no more complaints. He understood that this was the only way he could survive.

Excerpt from Willi Köhler’s medical records.

NLA Hannover Nds. 330 Lüneburg Acc. 2004/134 No. 00416.

»When his twin brother died recently, W. was very upset, cried a lot and didn’t eat well. In a letter to his mother, he asked for a mourning ribbon.«

Excerpt from Willi Köhler’s medical records.

NLA Hannover Nds. 330 Lüneburg Acc. 2004/134 No. 00416.

Excerpt from medical records, list of belongings of Wilhelm Schaffrath, 1943.

NLA Hanover Hann. 155 Lüneburg Acc. 56/83 No. 375.

At the beginning of July 1943, the Waldniel »Children’s ward« was dissolved. 183 children and adolescents were divided among the »Children’s wards« in Ansbach, Görden, Uchtspringe, Ueckermünde and Lüneburg. On 3 July 1943, a total of 38 children and adolescents from Waldniel were taken to the Lüneburg »Children’s ward«. Between July 1943 and December 1945, at least 25 died, one of whom was Wilhelm Schaffrath.

WILHELM SCHAFFRATH (1936 – 1943)

Excerpt from medical records, list of belongings of Wilhelm Schaffrath, 1943.

NLA Hanover Hann. 155 Lüneburg Acc. 56/83 No. 375.

Wilhelm Schaffrath from Euskirchen arrived in Waldniel 14 days before the closure of the »Children’s ward«. Only nine weeks passed between his admission there and his murder in Lüneburg, as Willi Baumert considered him to be

»completely anti-social and unworthy of life«

NLA Hanover Hann. 155 Lüneburg Acc. 56/83 No. 375.

was assessed. He arrived in Lüneburg with only the clothes he was wearing. That was all he had been given.

At the age of six, Wilhelm Schaffrath and his four siblings were placed in care. They had experienced a great deal of violence at home. The violence did not stop in care either. Wilhelm was forcibly admitted to the »Children’s ward« as »uneducable«.

Excerpt from the welfare education report dated 22 April 1943.

NLA Hanover Hann. 155 Lüneburg Acc. 56/83 No. 375.

From 1944 onwards, the Lüneburg »Children’s ward« took in around ten children from the Netherlands and Belgium. They had fled with or without their parents and were registered for admission to the »Children’s ward« by helpers from the NSV (National Socialist People’s Welfare Organisation). Others were children of forced labourers from Russia, the Soviet republics and Poland. They initially came with their mothers to the »foreigners« collection point’ or had been taken away from their mothers in the camp.

Cover of Luba Gorbatschuk’s medical file, 1944.

NLA Hanover Hann. 155 Lüneburg Acc. 56/83 No. 67.

The children of forced labourers usually survived only a few weeks because the costs of their care were not covered. It did not matter whether they were actually ill or developmentally delayed. Luba Gorbatschuk (1943–1944) was sent to the »Children’s ward« because her mother had run away from the camp and the camp administration wanted to get rid of her. Luba had no abnormalities whatsoever, except that she was just getting her first teeth.

Benni Hiemstra’s Dutch parents were National Socialists. In August 1944, they fled to the Reich, hoping to escape the Allies. Benni was seven years old when he was registered at the refugee camp school in Amelinghausen and then admitted to the »Children’s ward«. He died within just three weeks.

Benni Hiemstra, around 1938.

Private collection Johan Huismann | Tine Ovinck-Huismann.

Letter from the City of Lüneburg regarding the assumption of costs dated 20 February 1945.

NLA Hanover Hann. 155 Lüneburg Acc. 56/83 No. 136.

Elisabeth van Molen and Dieter Lorenz had been brought to the Reich from the Netherlands without their parents as part of the NSV Youth Welfare West campaign. They were murdered after only a few days. The decisive factor in their case was that the city of Lüneburg hesitated to cover the care costs for the parentless children. It was not until February 1945 that the city decided to bear the costs. By then, both children were already dead.

DIETER LORENZ (1942 – 1944)

Family photo with Dieter, Rolf and Helmut Lorenz (foreground, from left to right), Aenne and Erich Lorenz behind them, and Heinrich Wilhelm Vennemann, Dieter’s grandfather, at the very back, circa autumn 1942.

Private collection of Helmut Lorenz.

Dieter Lorenz was born on 26 February 1942 in Eindhoven in the Netherlands. His father Erich was a businessman and came from Schmölln in Thuringia. His mother Aenne (née Vennemann) was Dutch and a pharmacist. They married in 1934 and had three sons: Rolf, Helmut and Dieter.

Rolf, Dieter and Helmut Lorenz, Eindhoven, spring 1943.

Private collection of Helmut Lorenz.

Because Erich was drafted into the Wehrmacht and Aenne had to run the tool shop on her own from then on, she temporarily placed Dieter in a children’s home. At the beginning of September 1944, it was evacuated without informing the parents. The futile search for Dieter began. Erich had himself transferred to commandos where Aenne had learned that Dieter might be in the respective area.

Memo, no author, no date, December 1944.

Private collection of Helmut Lorenz.

Dieter came via Hilden near Solingen and Hanover to Lüneburg, where he was placed in a reception camp for parentless children. There he was selected and admitted to the Lüneburg »Children’s ward« on 28 November 1944. He had a box with him on which his name »Lorenz« was written. Because Rita Breker, a girl from the children’s home, referred to him as her »brother Dieter«, he was admitted as »Dieter Lorenz«.

Letter from the Hilden Welfare and Youth Services Department to the Solingen NSDAP district leadership, 16 January 1945.

Private collection of Helmut Lorenz.

When he was admitted, Dieter was diagnosed with a mental disability. Because it was assumed that he had no parents and the city of Lüneburg initially refused to cover the costs for the non-German child, he was murdered 16 days after his admission. Dieter died on 14 December 1944.

Letter dated 20 February 1945.

NLA Hanover Hann. 155 Lüneburg Acc. 56/83 No. 311.

On 20 February 1945, the city of Lüneburg agrees to cover the costs of Dieter’s stay. By then, he has already been dead for over two months.

Dieter’s parents only learned of his death in January 1945. His brothers never found out that Dieter had a disability. They were told that he had gone missing on a Red Cross bus. Helmut Lorenz then spent almost 70 years searching for his little brother. In 2014, Dieter’s fate was finally revealed.

Postcard of the Eben-Ezer institution in Lemgo, after 1945.

NArEGL 99.

Around 40 percent of the children and young people admitted to the Lüneburg »Children’s ward« survived. 103 children (39 girls, 64 boys) were transferred to Lemgo (Eben-Ezer) for an »educational experiment«. There was a special school there. Eleven of them were sent back, and Gertrud Krebs and Kurt Bock died as a result. The Eben-Ezer Foundation was not a safe place either. Twelve other children and adolescents are known to have been admitted to the »Children’s ward« by the foundation itself.

Because she knew her name and age, behaved well and showed interest, Willi Baumert transferred Gertrud Krebs to Eben-Ezer just six weeks after her admission. A year later, she returned as »unfit for school«. In November 1944, Max Bräuner noted in handwriting that there had been no visits or inquiries. This was also unlikely because she had initially been admitted from a children’s home in Amt Neuhaus. Three months after this entry, she was no longer alive.

Excerpt from the medical records of Gertrud Krebs.

NLA Hannover Hann. 155 Lüneburg Acc. 56/83 No. 110.

back

BADANIA I OSTATNIE LATA WOJNY

W 1948 roku Willi Baumert przyznał, że udał się do Berlina, do »Kancelarii Führera«, aby dowiedzieć się, jakie są cele i zadania »działu ds. dzieci«. Hans Hefelmann poinformował go, że prowadzone są badania nad dziećmi i młodzieżą w celu ustalenia przyczyn ich niepełnosprawności. Wyniki tych badań miały przyczynić się do zapobiegania chorobom i niepełnosprawności. Ponadto planowano udoskonalić »Ustawę o zapobieganiu chorobom dziedzicznym«.

Fragment protokołu z sekcji zwłok 338 dzieci i młodzieży, w tym przypadku Friedricha Dapsa, z dnia 23 marca 1942 r.

Kolekcja prywatna, Instytut Historii i Etyki Medycyny, Hamburg.

Z jednej strony badania przeprowadzano poprzez obserwację i testy inteligencji. Z drugiej strony dzieci i młodzież poddawano badaniom fizycznym. W tym celu pobierano krew i płyn mózgowo-rdzeniowy oraz usuwano narządy z ciał dzieci. W piwnicy budynku nr 25 urządzono pomieszczenie, w którym można było otwierać zwłoki. Willi Baumert przeprowadził 338 takich operacji i usunął mózgi. Zbadał je i wszystko zapisał.

Przekazał wiele organów do Centrum Medycznego Uniwersytetu w Hamburgu-Eppendorf (udokumentowano około 37 darowizn). Tam wykonano preparaty przekrojowe o grubości zaledwie kilku mikrometrów. Kiedy Willi Baumert musiał powrócić na front w sierpniu 1944 roku, Max Bräuner przejął zadanie pobierania i badania mózgów.

Szkiełko mikroskopowe z preparatem autorstwa Marianne Begemann, Centrum Medyczne Uniwersytetu w Hamburgu-Eppendorf (UKE), 1942 r.

Instytut Historii i Etyki Medycyny, Hamburg.

Oto imiona dzieci i młodzieży, których mózgi i inne narządy zostały przekazane Centrum Medycznemu Uniwersytetu w Hamburgu-Eppendorf (UKE):

Anita, Helga i Helmut Volkmerowie, około 1937 roku.

Własność prywatna Marlene Volkmer.

Pierwszym mózgiem wysłanym do Hamburga w celach badawczych był mózg Helgi Volkmer. Została ona zamordowana 30 listopada 1941 r. i była jedną z pierwszych ofiar programu »eutanazji dzieci« w Lüneburgu. Jest ona dowodem na to, że »specjalistyczny oddział dziecięcy« w Lüneburgu nie rozpoczął swojej działalności w 1942 r. wraz z przyjęciem pierwszych dzieci z »Reichsausschuss«, ale wraz z przybyciem dzieci z instytucji Rotenburga należących do Inner Mission.

Hans Jacob, po 1945 r.

Lawrence Zeidman: Nauka o mózgu pod swastyką. Naruszenia zasad etycznych, opór i represjonowanie neurobiologów w nazistowskiej Europie, Oxford 2020.

W UKE badacz mózgu Hans Jacob wykorzystywał do swoich badań organy pochodzące z Lüneburga. Pracował on dla »Reichsausschuss« (Komisji Rzeszy). Wielu badaczy mózgu współpracowało z instytucjami zajmującymi się »zabijaniem« i badaniami. Hans Heinze (Görden) i Julius Hallervorden (Berlin) byli nawet obecni podczas mordowania pacjentów, aby natychmiast po śmierci rozpocząć badania i gromadzenie próbek.

Willi Baumert był szczególnie zainteresowany dziećmi, u których podejrzewał zespół Hurlera. To również powód, dla którego pobrano tak wiele wycinków mózgu Heinricha Herolda z Duingen.

Heinrich Herold, Helmut Sievers i Irmgard Herold (od lewej do prawej) przed domem rodzinnym w Duingen, 1938 r.

Własność prywatna Holgera Sieversa.

Własność prywatna rodziny Schäfer.

To ostatnie zdjęcie Heinza Schäfera, wykonane jesienią 1941 roku. Kilka tygodni później trafił na oddział dziecięcy w Lüneburgu i wkrótce potem zmarł. Jego rodzice nie mogli w to uwierzyć. Ojciec pojechał do Lüneburga i kazał otworzyć trumnę, aby się upewnić. Głowa Heinza była zabandażowana. Rodzina nie potrafiła tego wyjaśnić, ponieważ Heinz oficjalnie zmarł na »błonicę i zapalenie płuc« .

Rodzinom nie powiedziano, że mózgi zostały usunięte. Śmierć Heinza Schäfera była stałym źródłem spekulacji w rodzinie. W 2012 roku próbki mózgu przechowywane w UKE zostały zidentyfikowane jako należące do niego. Rodzina po raz pierwszy została poinformowana o jego prawdziwym losie. Po wielu dziesięcioleciach w końcu otrzymali odpowiedź na pytanie, dlaczego głowa Heinza była zabandażowana. Willi Baumert i Hans Jacob wykorzystali jego mózg do swoich badań.

Transkrypcja Williego Baumerta dotycząca badania mózgu Heinza Schäfera, 1942 r.

Pierwsza strona notatek Hansa Jacoba dotyczących badania mózgu Heinza Schäfera, Centrum Medyczne Uniwersytetu w Hamburgu-Eppendorf, 1942 r.

Instytut Historii i Etyki Medycyny w Hamburgu.

Te fragmenty zawierają szokujące obrazy. Ich pokazywanie budzi kontrowersje. Te fragmenty zawierają szokujące obrazy. Ich pokazywanie budzi kontrowersje.

Sam zdecyduj, czy chcesz otworzyć wysuwaną półkę.

Wanna do otwierania zwłok, ok. 1941 r.

ArEGL.

W październiku 2023 r. wanna ta została znaleziona w piwnicy budynku nr 25, w miejscu dawnego »oddziału dziecięcego«. Najprawdopodobniej jest to wanna do przeprowadzania sekcji zwłok. Ślady w piwnicach budynku nr 25 wskazują, że ciała dzieci i młodzieży nie były wówczas przenoszone przez teren placówki do oficjalnej sali sekcyjnej, ale były otwierane na miejscu, w budynku nr 25.

To niepokojące zdjęcia. Przedstawiają chłopca i dziewczynkę w ogromnym cierpieniu i nędznych warunkach. Tożsamość tych dwojga dzieci nie jest znana. Willi Baumert wykorzystał te zdjęcia w swoich »badaniach«. Są to obraźliwe, przerażające zdjęcia. Bezlitośnie pokazują brutalność i nieludzkie traktowanie, jakiego dzieci doświadczały na »oddziale dziecięcym« w Lüneburgu. Tylko z tego powodu je pokazujemy.

Pięć zdjęć dzieci, wykonanych na oddziale dziecięcym w Lüneburgu w latach 1942/1943. Autorka zdjęć: Ruth Supper.

ArEGL FB 2/34.

Inge Roxin, »Oddział dziecięcy« Lüneburg 1943.

Własność prywatna Sigrid Roxin.

Dzieciom podawano patogeny, aby zbadać skuteczność nielicencjonowanego leku »Eubasin«. Mariechen Petersen nie chorowała tylko wtedy, gdy mogła ją odwiedzać matka. »Eubasin« zadziałał na jej sąsiadkę Inge Roxin. Wyzdrowiała, zanim Willi Baumert ją zamordował.

To zdjęcie zostało zrobione na »oddziale dziecięcym«. Widać na nim, że Inge Roxin była w złym stanie zdrowia. Poddano ją eksperymentom na ludziach. To zdjęcie jest trudne. Ale nie pokazanie go oznaczałoby bagatelizowanie prawdziwego cierpienia. Nie ma zdjęcia Mariechen Petersen.

Nie jest pewne, czy w »oddziale pediatrycznym« w Lüneburgu przeprowadzano również badania kliniczne szczepionek przeciwko gruźlicy, szkarlatynie lub innym chorobom. W przeciwieństwie do leczenia dorosłych pacjentów, zwłaszcza w tak zwanym »ośrodku zbiorczym dla cudzoziemców«, nie ma na to jak dotąd żadnych dowodów w przypadku dzieci i młodzieży.

W badaniach prowadzonych na oddziale dziecięcym uczestniczyło wielu pracowników personelu pielęgniarskiego, ale także administracji i innych działów sanatorium i domu opieki w Lüneburgu. Żaden z nich nie podjął żadnych działań, aby zapobiec śmierci dzieci lub poprawić ich sytuację. Można ich zatem uznać za współwinnych.

Pismo do Dresdner Banku zawierające instrukcje dotyczące wypłaty »specjalnych dodatków« z dnia 15 grudnia 1943 r.

BArch NS 51/227.

Osoby zaangażowane w morderstwa na »oddziale dziecięcym« oraz ich wspólnicy otrzymali w nagrodę »specjalne dodatki«. Z listy tej wynika, że »oddział dziecięcy« w Görden otrzymał najwyższą kwotę »specjalnych dodatków«, ponieważ w 1943 r. uczestniczyło w nim szczególnie wielu uczestników i wspólników programu »eutanazji dzieci«. Lista nie obejmuje wszystkich »oddziałów dziecięcych«, w których w tym roku zamordowano dzieci i młodzież.

List Maxa Bräumera do »Komitetu Rzeszy« z dnia 28 listopada 1943 r.

BArch NS 51/227.

Pracownicy oddziału dziecięcego w Lüneburgu nie otrzymali żadnych »dodatkowych świadczeń« w 1941 roku. W 1942 roku pielęgniarki Wilhelmine Wolf i Dora Vollbrecht otrzymały po 30 marek niemieckich dodatkowego wynagrodzenia. W 1943 roku Max Bräuner zarekomendował pielęgniarki Wilhelmine Wolf i Herthę Walther oraz swojego starszego lekarza Williego Baumerta do otrzymania dodatkowych wynagrodzeń. Jako lekarz Baumert otrzymał 100 marek niemieckich, co oznacza, że w 1943 roku Lüneburg otrzymał łącznie 160 marek niemieckich od »Komitetu Rzeszy«.

Cała korespondencja między Komitetem Rzeszy a instytucją, raporty ekspertów, zapisy sporządzone podczas wizyt oraz protokoły z sekcji zwłok zostały sporządzone przez sekretarkę Karolę Bierwisch (z domu Kleim). Była ona nie tylko sekretarką dyrektora medycznego Maxa Bräumnera, ale także jego asystentką w badaniach nad środkami śmiertelnymi. Z tego powodu otrzymała również »specjalny dodatek« od »Komitetu Rzeszy« za rok 1944.

List Maxa Bräumera do »Komitetu Rzeszy« z dnia 7 grudnia 1944 r.

BArch NS 51/227.

List »Komitetu Rzeszy« do szpitala psychiatrycznego Kalmenhof z dnia 27 września 1944 r.

BArch NS 51/227.

W 1944 r. poszczególne pielęgniarki otrzymywały miesięczne dodatki w wysokości 35 marek niemieckich za udział w zabijaniu pacjentów. Pielęgniarki w Lüneburgu również otrzymywały takie dodatki. Miało to na celu wzmocnienie lojalności i zwiększenie motywacji.

Pismo ze szpitala psychiatrycznego w Großschweidnitz do Komitetu Rzeszy z dnia 4 października 1944 r.

BArch NS 51/227.

Osoby, które wykazały się wyjątkowymi zasługami w tak zwanej »pracy komitetu Rzeszy«, otrzymały medal. Zostały one odznaczone »Medalem Honorowym Niemieckiej Opieki Społecznej«. W ten sposób »doceniono« popełnione przez nie morderstwa.

Pielęgniarze August Gebhardt i Ernst Meier pomagali przy sekcjach zwłok na oddziale dziecięcym w Lüneburgu. Gebhardt był pielęgniarzem od 1912 roku, a od 1938 roku odpowiadał za otwieranie i ponowne zamykanie ciał. Chociaż matka Paula Hausena, ofiary programu »T4«, powiedziała mu, że uważa, iż jej syn został zamordowany, Gebhardt nie miał pojęcia, że wiele ciał dzieci, z którymi miał do czynienia, również było ofiarami eutanazji.

Fragment protokołu przesłuchania Augusta Gebhardta z dnia 1 listopada 1947 r.

NLA Hannover Nds. 721 Lüneburg Acc. 8/98 nr 3.

Przegląd personelu pielęgniarskiego na oddziale dziecięcym z dnia 4 października 1947 r.

NLA Hannover Nds. 721 Lüneburg Acc. 8/98 nr 3.

Dzieci i młodzież były pod opieką 21 pracowników pielęgniarskich pracujących na trzy zmiany. Oprócz trzech pielęgniarek Wilhelmine Wolf (główna pielęgniarka), Ingeborg Weber (która odebrała sobie życie i dlatego nie figuruje na liście) oraz Dory Vollbrecht, było wiele innych pielęgniarek, które zaniedbywały dzieci i młodzież, zapewniały im nieodpowiednią opiekę i patrzyły, jak umierają.

»W placówce pracuje siedem pielęgniarek, które opiekują się około 130 dziećmi. Nie ma możliwości zatrudnienia większej liczby personelu ze względu na trudności kadrowe spowodowane wojną. Można się również zastanawiać, czy można wziąć na siebie większą odpowiedzialność, biorąc pod uwagę bezwartościowość tych zasobów ludzkich w obecnej sytuacji wojennej.«

Fragment listu Maxa Bräumnera do Państwowego Urzędu Zdrowia w Wittmundzie z dnia 17 października 1942 r.

NLA Hannover Hann. 155 Lüneburg Acc. 56/83 nr 145, s. 2.

W »oddziale dziecięcym« w Lüneburgu przebywało 35 rodzeństw z 15 rodzin. Przyjmowano maksymalnie czworo dzieci z jednej rodziny. Czasami wszystkie dzieci były odbierane rodzicom. Nawet po wojnie wiele dzieci nie wróciło do domu. Spośród rodzeństwa tylko jedno ponownie zobaczyło swoich rodziców. Od 1945 r. młodzież była przekazywana do placówek opieki społecznej. Wielu ocalałych pozostało mieszkańcami placówki do lat 70.

ERIKA (1936–1944) I MARGRET BUHLRICH (1941–1945)

Hans Buhlrich, 1936.

Erika Buhlrich, około 1937 roku.

Margret Buhlrich, około lata 1944 roku.

Własność prywatna Friedricha Buhlricha.

Rodzeństwo Buhlrich z Bremy zostało wysłane do »oddziału dziecięcego« w Lüneburgu w 1944 roku. Ich brat Hans (1932–1942) zmarł już w 1942 roku w Kutzenbergu (Bawaria). Został ewakuowany z Gertrudenheim koło Bremy po zaledwie kilku dniach. Siostry zostały zamordowane około dwa lata później, aby zbadać ich mózgi pod kątem patologicznych predyspozycji i ustalić, czy ich matka nie powinna mieć czwartego dziecka. Podczas bombardowań były uważane za utrudnienie w schronie przeciwlotniczym sąsiadów. Matka była bardzo zainteresowana ustaleniem, dlaczego jej syn Hans miał kalekie ramię, a dwie córki miały opóźnienia rozwojowe. Aby znaleźć przyczynę, najpierw zmarła Erika, a następnie Margret. Kiedy rodzice dowiedzieli się, że Erika musiała mieć zapalenie opon mózgowych, ale przyczyna pozostałych zaburzeń pozostała niejasna, Buhlrichowie postanowili nie mieć więcej dzieci. Zamiast tego adoptowali dziecko urodzone przez Niemkę i polskiego robotnika przymusowego. Friedrich Buhlrich nie wiedział o istnieniu swoich trzech biologicznych rodzeństwa aż do śmierci swoich przybranych rodziców.

Dzieci były świadkami morderstwa i widziały, jak giną ich rodzeństwo. Tak samo było w przypadku bliźniaków Köhlerów. Stan zdrowia pogarszał się, a w styczniu 1945 roku 16-letni Herbert ważył zaledwie 28,5 kg. Zmarł 22 marca 1945 roku. Jego brat bliźniak Willi był przy nim. Ta strata bardzo go dotknęła. Potem jego brat pracował sumiennie, dbając o to, by nie było żadnych skarg. Rozumiał, że tylko w ten sposób może przetrwać.

Fragment dokumentacji medycznej Williego Köhlera.

NLA Hannover Nds. 330 Lüneburg Acc. 2004/134 nr 00416.

»Kiedy niedawno zmarł jego brat bliźniak, W. był bardzo smutny, dużo płakał i nie jadł dobrze. W liście do matki poprosił o czarną wstążkę żałobną.«

Fragment dokumentacji medycznej Williego Köhlera.

NLA Hannover Nds. 330 Lüneburg Acc. 2004/134 nr 00416.

Fragment dokumentacji medycznej, spis rzeczy osobistych Wilhelma Schaffratha, 1943 r.

NLA Hanower Hann. 155 Lüneburg Acc. 56/83 nr 375.

Na początku lipca 1943 r. rozwiązano »oddział dziecięcy« w Waldniel. 183 dzieci i młodzież rozdzielono między »oddziały dziecięce« w Ansbach, Görden, Uchtspringe, Ueckermünde i Lüneburgu. 3 lipca 1943 r. łącznie 38 dzieci i młodzieży z Waldniel zostało przewiezionych do »oddziału dziecięcego« w Lüneburgu. W okresie od lipca 1943 r. do grudnia 1945 r. zmarło co najmniej 25 osób, wśród nich Wilhelm Schaffrath.

WILHELM SCHAFFRATH (1936 – 1943)