NFC zu M9-01

UMGANG MIT DEM TOD

Familien hatten die Möglichkeit, die Toten oder die Urnen mit Asche nach Hause zu überführen und auf dem heimischen Friedhof zu begraben. Auf dem Lüneburger Anstaltsfriedhof wurden Gräberfelder für Kinder und für Erkrankte ausländischer Herkunft ausgewiesen. Viele Familien empfanden den Tod als »Erlösung«. Auch aus Scham überwog in vielen Familien ein jahrzehntelanges Schweigen. Selten wurde offen getrauert. Es gibt viele Angehörige, die deshalb erst heute vom Schicksal ihrer Verwandten erfahren.

Manche Familien wollen die Personen beerdigen.

Sie bekommen die Leiche.

Sie bekommen eine Urne.

Mit Asche eines Menschen.

In Lüneburg ist ein Anstalts-Friedhof.

Es gibt Bereiche.

Für Kinder.

Für »Ausländer«.

Viele Kranke sterben.

Viele Familien sind erleichtert.

Für sie ist der Tod etwas Gutes.

Eine Erlösung.

Viele Familien schämen sich.

Für den Kranken.

Sie reden nicht über den Kranken.

Sie erzählen nicht was passiert.

Viele Familien erfahren erst jetzt was mit dem Mensch geschehen ist.

In der Nazi-Zeit.

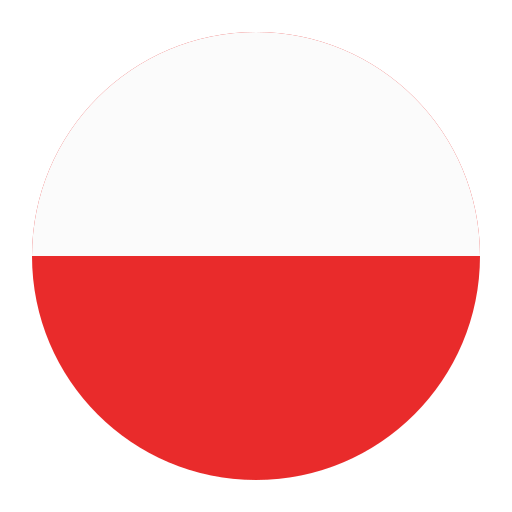

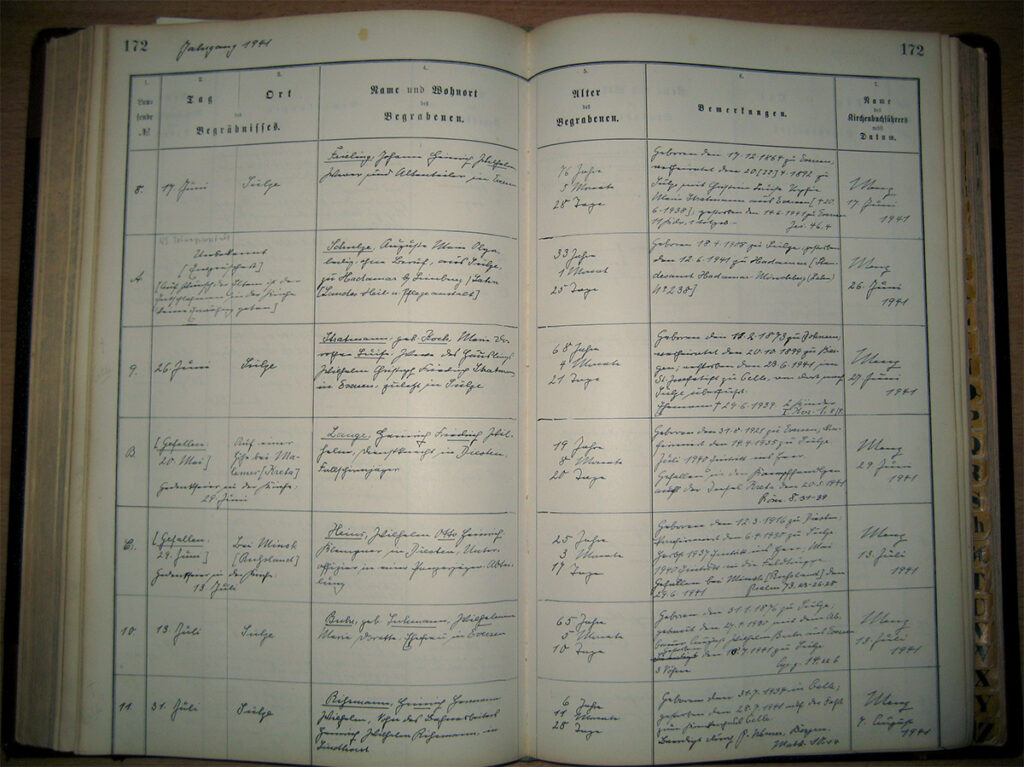

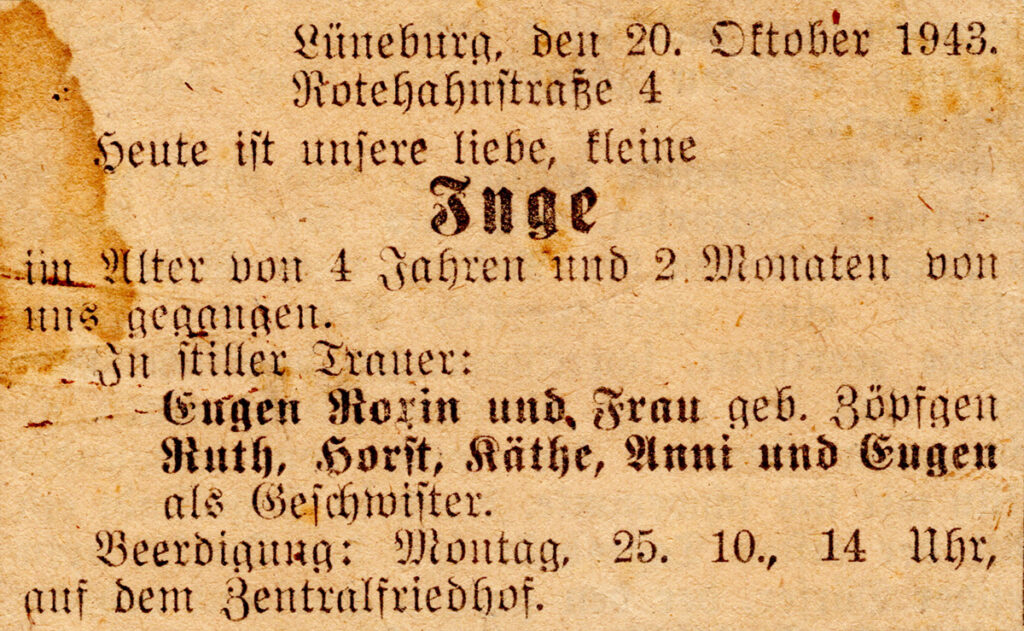

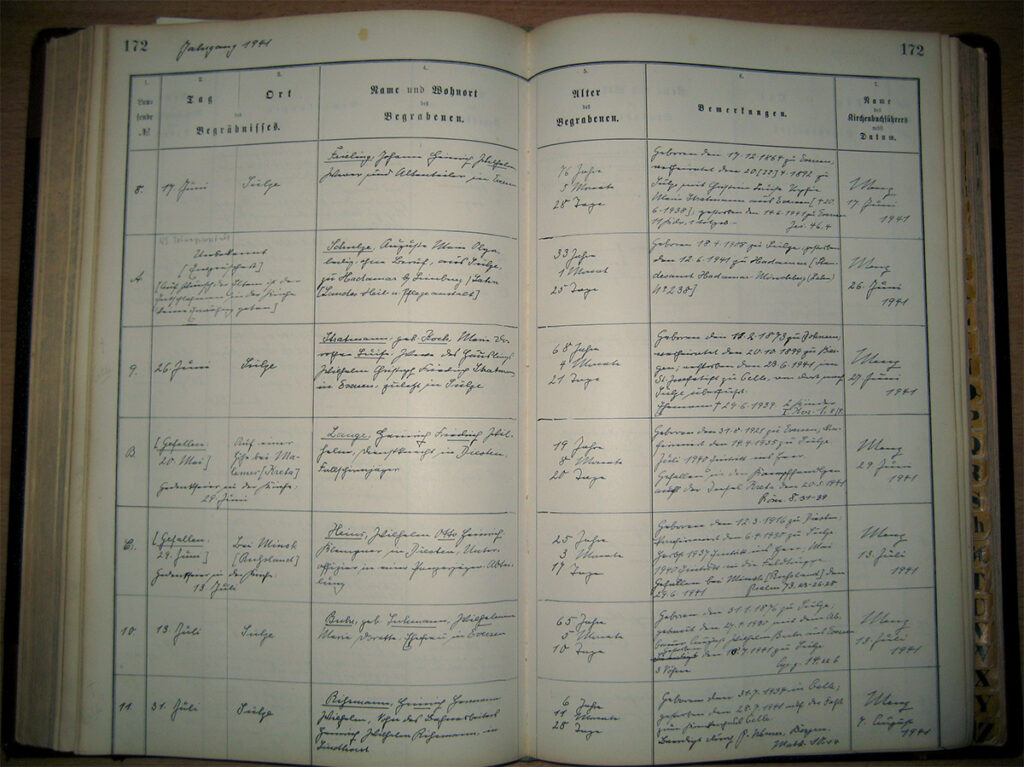

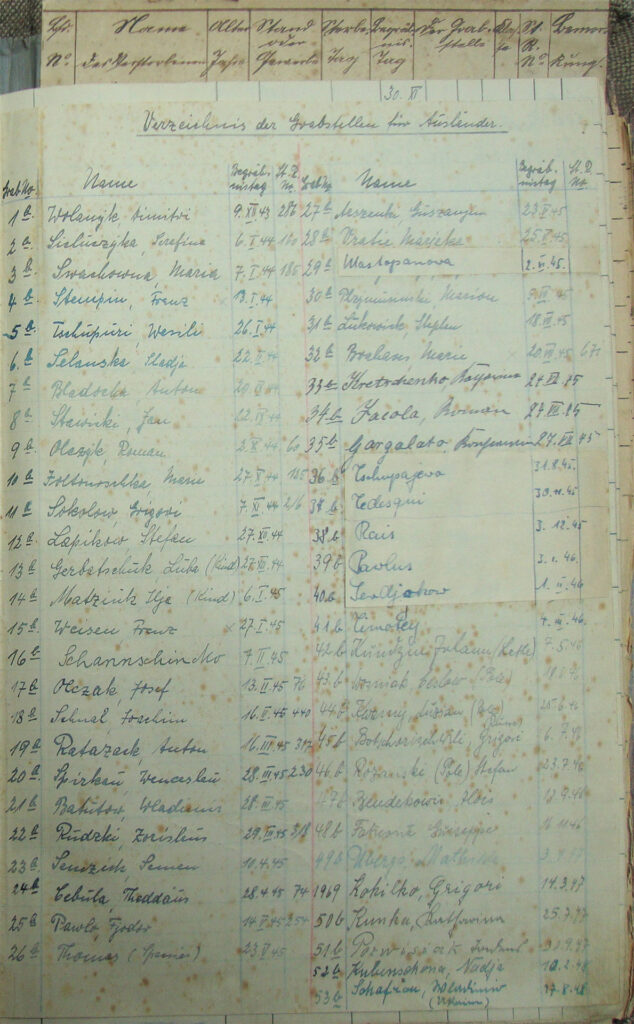

Auszug aus dem Sterbebuch der Kirchenegemeinde Sülze 1876 bis 1945, Seite 172 Nr. 8A.

ArEGL.

Es gab Familien, die sich aus den Tötungsanstalten Brandenburg, Pirna-Sonnenstein und Hadamar die Urne nach Hause schicken ließen. Die Asche der übrigen wurde weggekippt, etwa einen Abhang hinunter (Pirna-Sonnenstein). Die überstellten Urnen der Opfer der »Aktion T4« wurden auf Wunsch der Familien auf dem Heimatfriedhof beigesetzt. Viele nutzten hierfür bestehende Familiengräber. Es kam häufig vor, dass die Familien den Toten keine Beachtung schenkten.

In den Tötungs-Anstalten werden Menschen ermordet.

Danach werden die Leichen verbrannt.

Übrig bleibt Asche.

Manche Familien wollen die Asche haben.

Die Familien bekommen eine Urne mit Asche.

Die Familien beerdigen die Urne.

In einem Familien-Grab.

Manche Familien wollen aber auch nichts von den Toten wissen.

Vielen Familien ist es egal.

Die Asche von den Menschen wird weg-gekippt.

Zum Beispiel einen Ab-Hang.

In Pirna-Sonnenstein.

»*18.4.1908 Sülze, gestorben zu

Hadamar b. Limburg/Lahn (Landes Heil- und Pflegeanstalt)

(Standesamt Hadamar Mönchberg (Lahn) Nr. 238). Beerdigungsort unbekannt (eingeäschert) (auf Wunsch der Eltern ist

der Entschlafenen in der Kirche keine Erwähnung getan).«

Das ist ein Sterbe-Buch.

Im Sterbe-Buch stehen viele Namen.

Und Daten.

Von toten Menschen.

Das Sterbe-Buch ist aus der Kirche.

In Sülze.

Zu den Jahren 1876 bis 1945.

Im Buch steht Olga Schulze.

Olga Schulze wird ermordet.

In Hadamar.

Ihre Eltern sagen:

Bitte unsere Tochter nicht erwähnen.

Nicht im Gottes-Dienst.

Keiner soll es wissen.

Dass Olga in Hadamar gestorben ist.

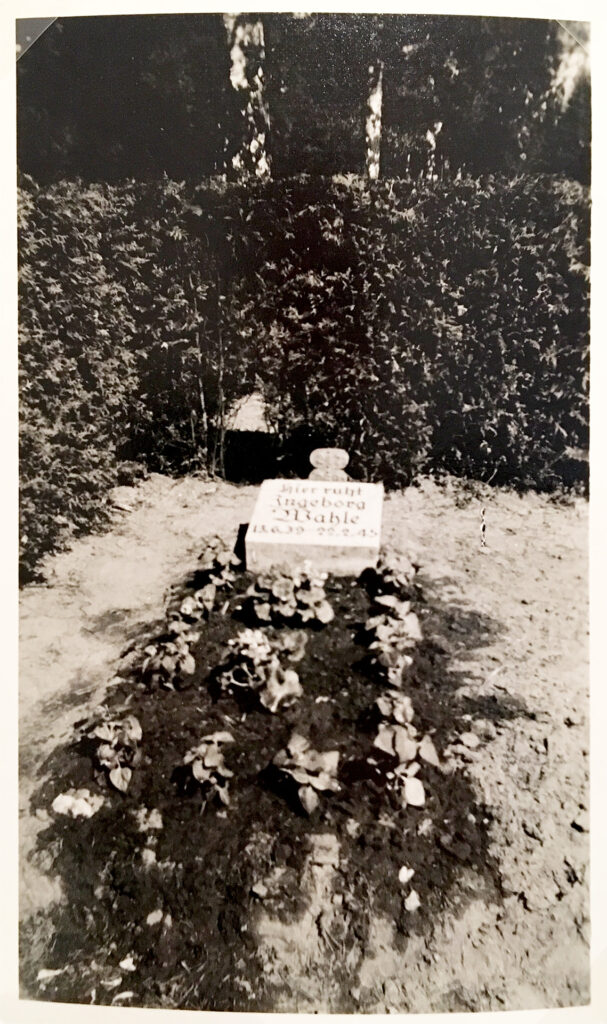

Die Urne mit Therese Schuberts angeblicher Asche wurde nach Lüneburg überführt und auf dem Zentralfriedhof hinzugebettet. Die Friedhofsverwaltung forderte die Familie auf, sich wegen der Auflösung des Grabes bei der Verwaltung zu melden. Doch Therese Schuberts Sohn Theo stellte das Schild in ein anderes Grab und ignorierte die Aufforderung. Das Grab steht seit 2014 auf der Liste der historischen Gräber der Stadt Lüneburg und ist somit auf Dauer geschützt.

Das ist ein Grab.

Von Therese und Heinrich Schubert.

Therese Schubert wird ermordet.

Ihre Urne kommt nach Lüneburg.

Therese Schubert hat ein Grab.

Auf dem Zentral-Friedhof.

Später ist ein Schild auf dem Grab.

Von der Verwaltung.

Die Familie soll sich melden.

Das Grab soll weg.

Die Familie nimmt das Schild weg.

Die Familie meldet sich nicht.

Das Grab bleibt.

Bis heute.

Das Grab ist historisch.

Seit 2014 ist das Grab geschützt.

Für immer.

Das Grab von Therese und Heinrich Schubert auf dem Zentralfriedhof Lüneburg, 2014.

ArEGL.

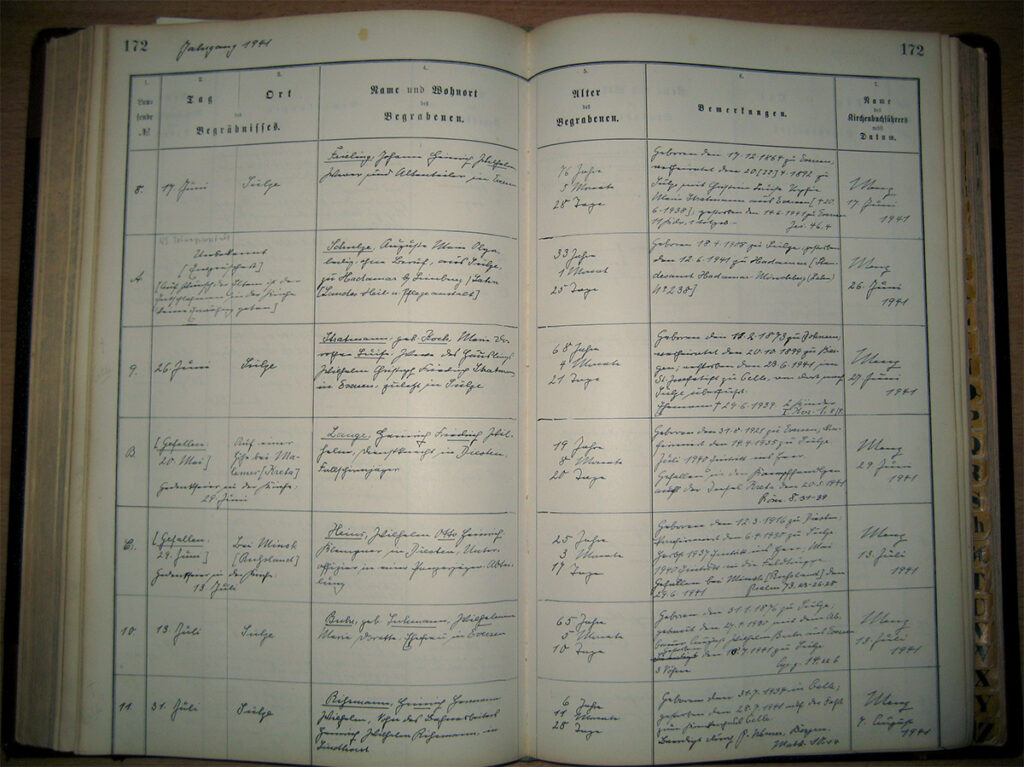

Grab von Wilhelm Müller, 2016.

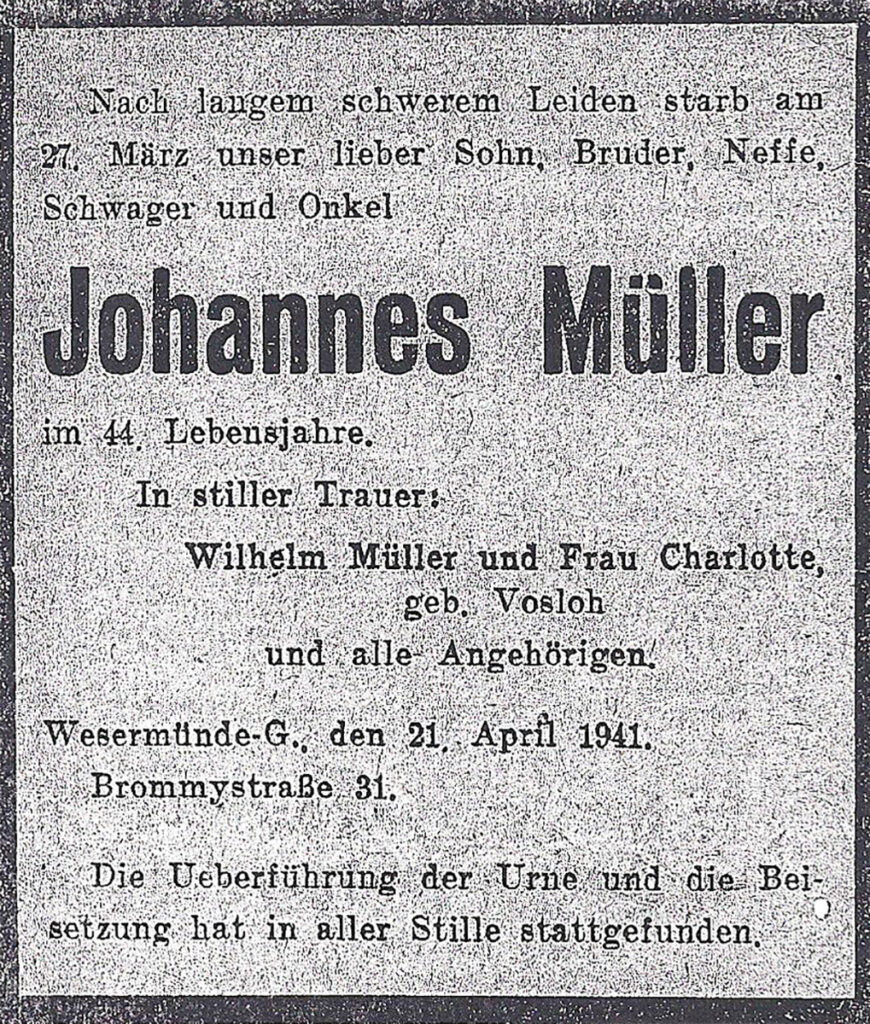

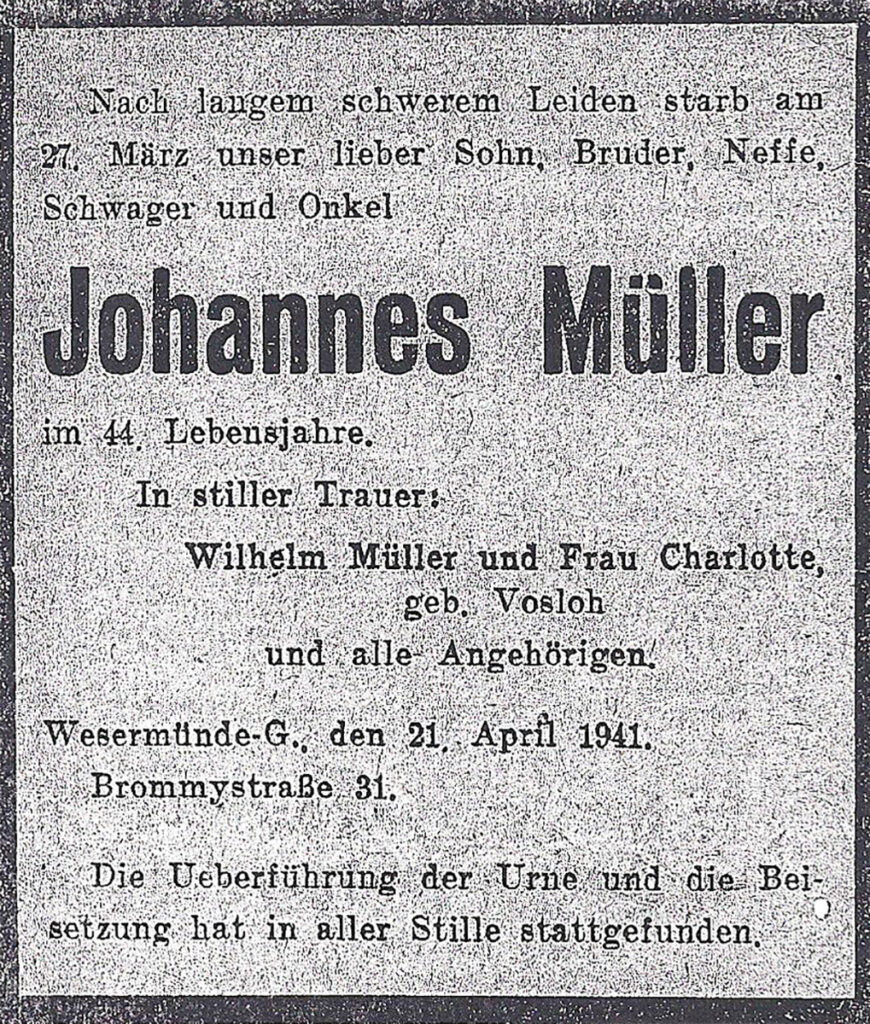

Sterbeanzeige für Johannes Müller. Geestemünder Anzeiger, April 1941.

Privatbesitz Familie Helga und Ludwig Müller.

Als Wilhelm Müller starb, wurde er in das Grab seines Sohnes hinzugebettet und ein Grabstein gesetzt. Johannes Müller wurde am 7. März 1941 in Pirna-Sonnenstein ermordet. Weil seine Familie die Urne überführen ließ, wurde eine Urne mit seiner vermeintlichen Asche nicht am Elbhang verstreut, sondern auf dem Friedhof in Bremerhaven beigesetzt. Die Familie trauerte auch öffentlich um ihr Familienmitglied.

Johannes Müller wird ermordet.

Am 7.3.1941.

In Pirna-Sonnenstein.

Seine Leiche wird verbrannt.

Seine Asche wird nicht verstreut.

Die Familie möchte seine Asche.

In einer Urne.

Die Urne kommt auf den Friedhof.

In Bremerhaven.

Es ist nicht sicher ob die Asche von Johannes stammt.

Der Tod wird in der Zeitung gemeldet.

Die Familie trauert.

Sie versteckt ihre Trauer nicht.

Dann stirbt der Vater von Johannes.

Der Vater bekommt ein Grab.

Neben Johannes.

Das Grab bekommt einen Stein.

Für Beide.

Grablagen auf dem Lüneburger Anstaltsfriedhof, um 1945.

ArEGL 16-3.

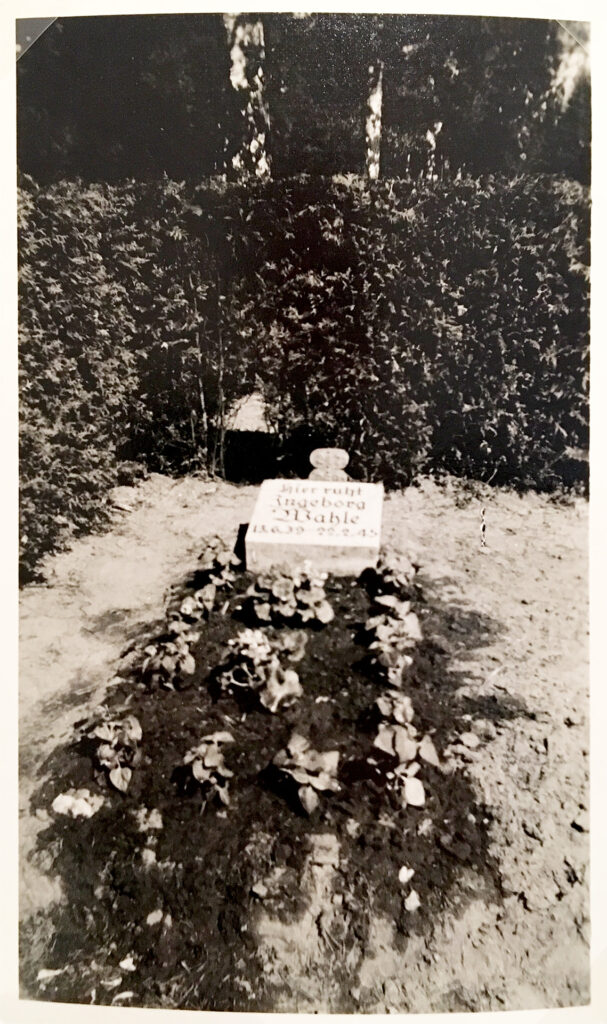

Martha Ossmers Eltern fotografierten das Grab ihrer Tochter, als sie es nach der Beisetzung besuchten. Viele Familien hatten keine Möglichkeit, bei der Beerdigung ihrer Angehörigen dabei zu sein.

Privatbesitz Christel Banik.

Alle Gräber auf dem Anstaltsfriedhof erhielten ein schlichtes Holzkreuz. Es trug oft nur die Grabnummer oder den Namen. Die Bepflanzung war schlicht. Angehörige hatten die Möglichkeit, das Holzkreuz auf eigene Kosten durch einen Stein zu ersetzen.

Das ist ein Foto.

Auf dem Foto sind Gräber.

Auf dem Anstalts-Friedhof.

Auf dem Anstalts-Friedhof sind viele Gräber.

Jedes Grab hat ein Holz-Kreuz.

Auf dem Kreuz ist eine Nummer.

Oder der Name.

Es gibt wenige Pflanzen.

Familien können einen Stein setzen.

Familien bezahlen den Stein.

Das ist das Grab von Martha Ossmer.

Die Eltern machen das Foto.

Die Eltern besuchen das Grab.

Die Eltern kommen nach der Beerdigung.

Die Beerdigung ist oft ohne Familie.

Wenige Familien können dabei sein.

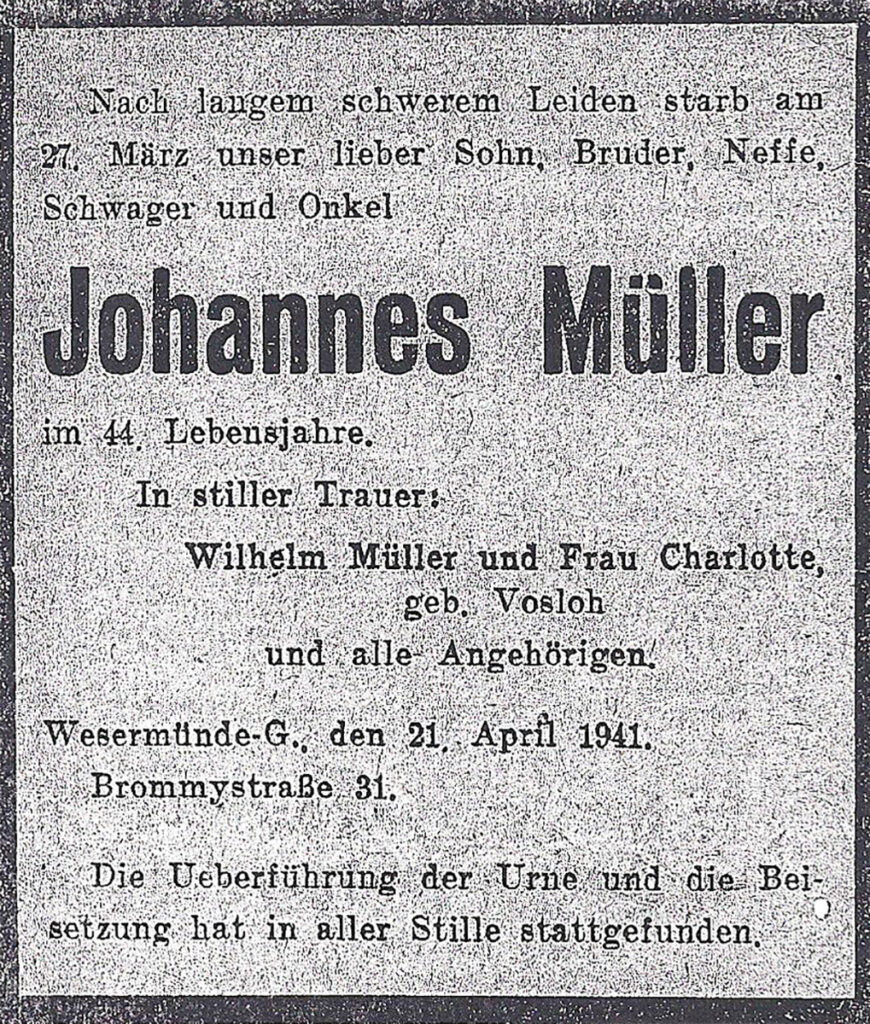

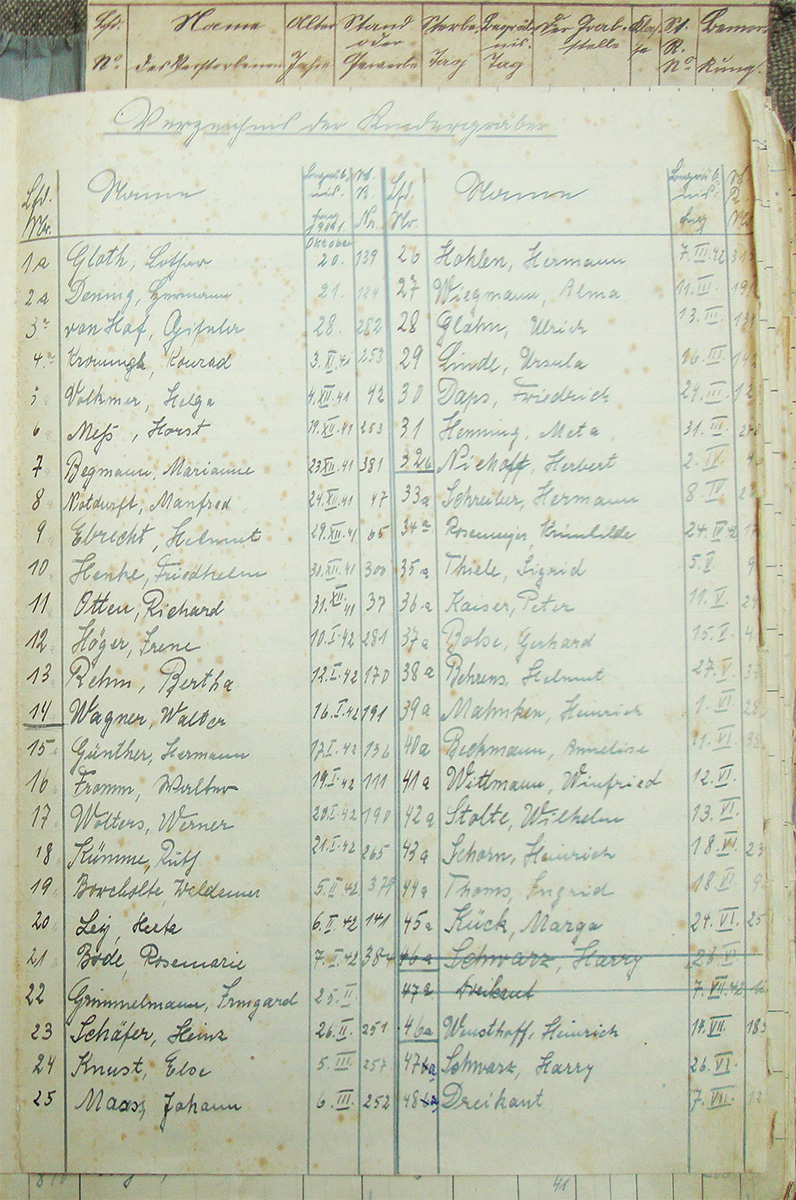

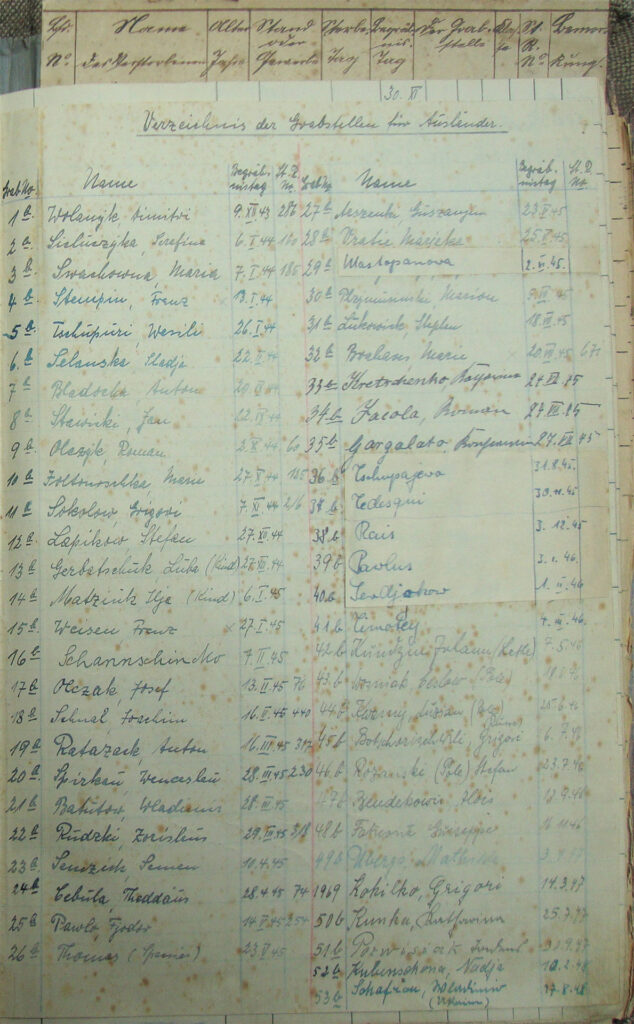

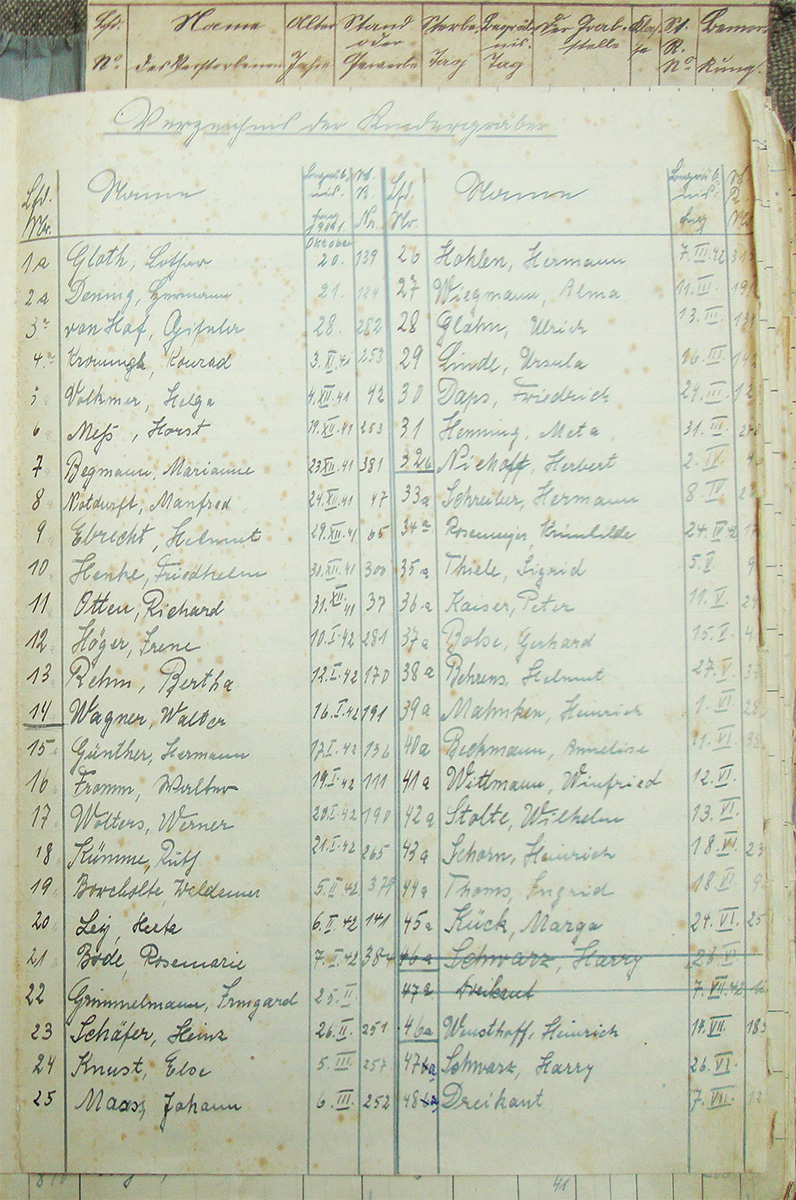

Auszug aus dem Begräbnisbuch [zum Friedhof der Heil- und Pflegeanstalt Lüneburg] von 1922 – 1948.

StadtALg, FHA, 235.

297 ermordete Kinder und Jugendliche der Lüneburger »Kindereuthanasie« wurden auf zwei Kindergräberfeldern auf dem Anstaltsfriedhof bestattet. Mindestens acht weitere Kinder wurden dort in Streulage in Erwachsenen-Gräbern bestattet, aus Mangel an Kindersärgen. Die Kinder mit Familie in Lüneburg wurden auf Wunsch der Eltern auf dem Zentralfriedhof bestattet. Es gibt auch ermordete Kinder, deren Grablage bis heute unbekannt ist.

297 Kinder werden ermordet.

Sie sind Opfer vom Kinder-Kranken-Mord.

Sie werden bestattet.

Sie bekommen Gräber.

Die Gräber sind auf dem Anstalts-Friedhof.

In zwei Bereichen.

In den Bereichen sind nur Kinder-Gräber.

Die Kinder werden in einem Sarg bestattet.

In einem kleinen Sarg.

Manchmal fehlt ein kleiner Sarg.

Dann bekommt das Kind einen großen Sarg.

Mindestens für 8 Kinder.

Die Kinder bekommen einen großen Sarg.

Das Grab ist bei den Erwachsenen.

Es ist dann nicht auf dem Kinder-Gräber-Feld.

Manche Kinder kommen aus Lüneburg.

Die Familien wünschen sich:

Das Grab ist auf den Zentral-Friedhof.

Manche Kinder-Gräber fehlen.

Wir wissen nicht wo sie sind.

Besuch des Anstaltsfriedhofs, ca. 1946/1947.

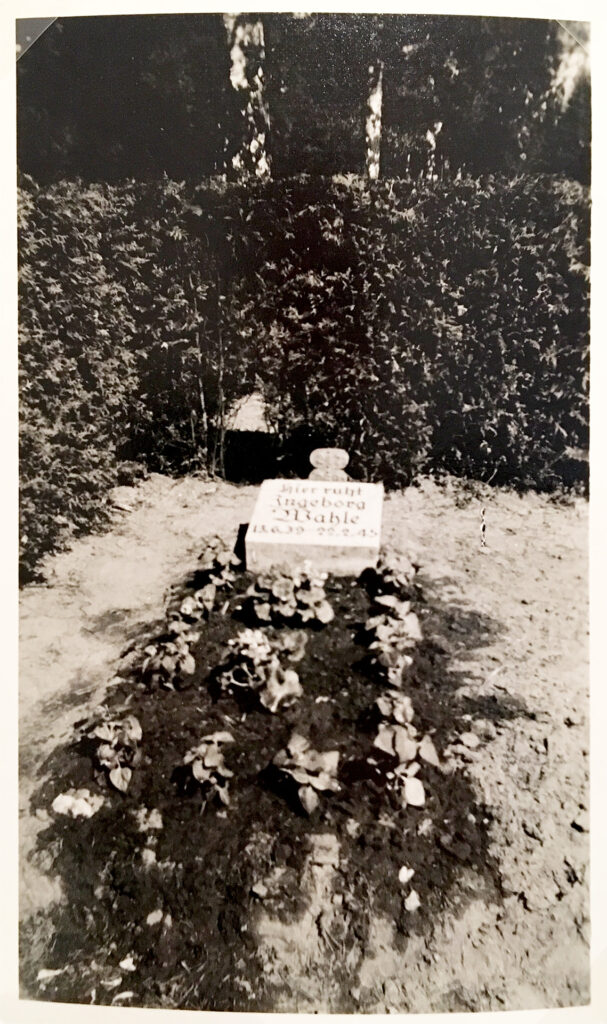

Grab von Ingeborg Wahle, 1945. Auf dem Grabstein ist der 22. Februar als Todestag vermerkt. Sie starb jedoch zwei Tage später.

Privatbesitz Renate Beier.

Die Eltern der ermordeten Kinder ließen es sich oft nicht nehmen, die Gräber selbst zu pflegen, obwohl die Provinz Hannover für alle auf dem Anstaltsfriedhof liegenden Gräber die Pflegekosten übernahm. Ingeborg Wahles Eltern fuhren mehrmals im Jahr nach Lüneburg, um das Grab ihres Kindes zu pflegen. Sie ließen auch das Holzkreuz durch einen Kissenstein ersetzen. In den 1960er-Jahren war er plötzlich weg, ohne dass die Angehörigen benachrichtigt worden waren.

Die ermordeten Kinder bekommen ein Grab.

Auf dem Anstalts-Friedhof.

Der Staat bezahlt das Grab.

Der Staat bezahlt die Pflege vom Grab.

Trotzdem:

Viele Familien pflegen die Gräber.

Ingeborg Wahle ist tot.

Sie hat ein Grab.

Die Eltern kommen nach Lüneburg.

Sie kommen oft.

Sie legen einen Grab-Stein auf das Grab.

Der Grab-Stein ist plötzlich weg.

Die Familie bekommt keine Nachricht.

Das ist ein Grab.

Das Grab von Ingeborg Wahle.

Auf dem Grabstein steht:

Gestorben am 22. 2. 1954

Das ist falsch.

Ingeborg Wahle stirbt zwei Tage später.

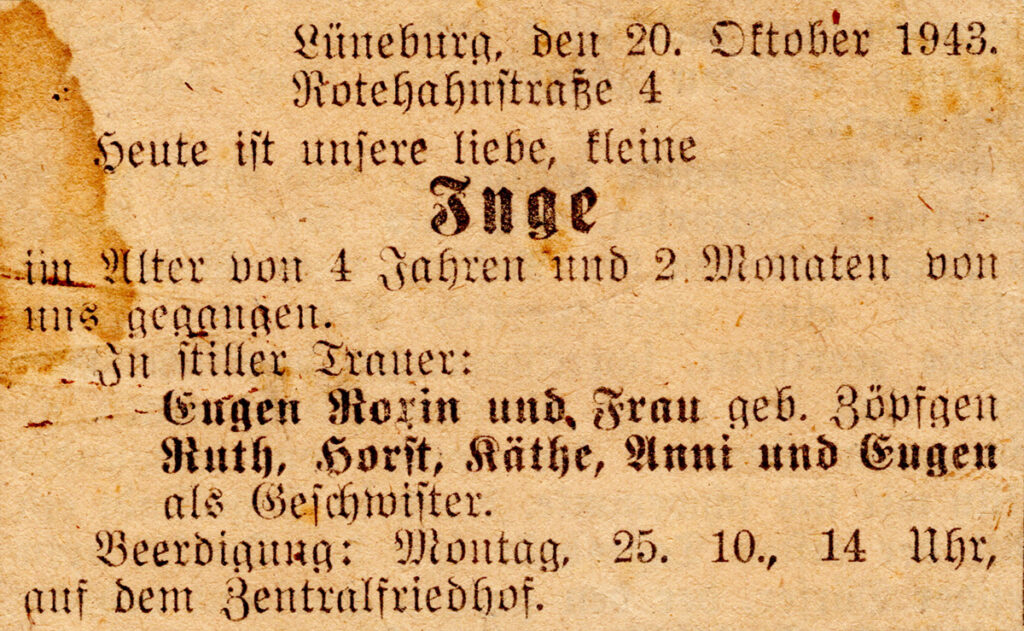

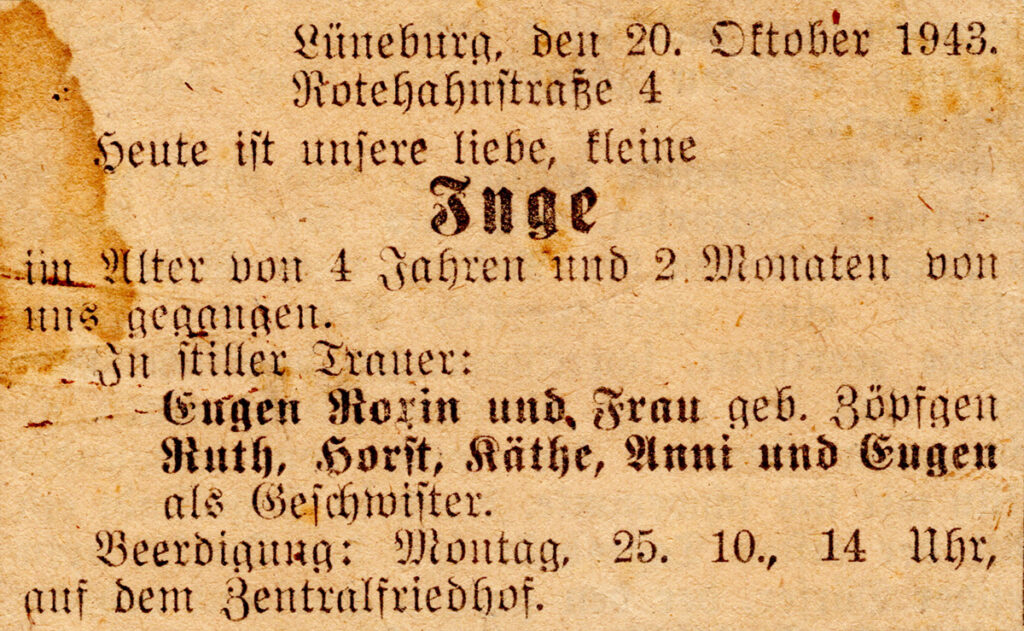

Obwohl die Eltern von Inge Roxin kein Geld hatten, ließen sie es sich nicht nehmen, eine Traueranzeige in den Lüneburger Anzeigen zu schalten, zur Beerdigung einzuladen und Inge auf eigene Kosten auf dem Zentralfriedhof beizusetzen. Damit nahmen die Eltern fortan auch auf sich, für die Grabpflege aufzukommen. Das war ihnen Inge wert.

Die ermordeten Kinder bekommen ein Grab.

Auf dem Anstalts-Friedhof.

Der Staat bezahlt das Grab.

Der Staat bezahlt die Pflege vom Grab.

Trotzdem :

Viele Familien pflegen die Gräber.

Traueranzeige für Inge Roxin, Lüneburger Anzeigen, Oktober 1943.

Privatbesitz Sigrid Roxin.

Grab von Christian Meins auf dem Zentralfriedhof Lüneburg, September 2021.

ArEGL.

Weil er als »bombenbeschädigtes Kind« eingewiesen worden war, wurde Christian Meins nicht auf dem Anstalts-, sondern auf dem Zentralfriedhof Lüneburg auf einem Gräberfeld für Bombenbeschädigte aus Hamburg bestattet. 1952 fiel sein Grab unter das Kriegsgräbergesetz. Es ist deshalb bis heute als Einzelgrab mit Grabplatte erhalten.

Die im Städtischen Krankenhaus Lüneburg ermordeten Zwangsarbeiter*innen wurden ebenfalls auf dem Zentralfriedhof der Stadt Lüneburg bestattet. Ihre Familien wurden weder über den Tod noch über den Bestattungsort informiert.

Christian Meins hat ein Grab.

Auf dem Zentral-Friedhof in der Stadt.

In einem besonderen Bereich:

Für Bomben-Opfer aus Hamburg.

Obwohl Christian Meins gar kein Bomben-Opfer ist.

Aber:

Er war als Bomben-Opfer eingewiesen.

Im Jahr 1952 gibt es ein Gesetz.

Das Gesetz heißt:

Kriegs-Gräber-Gesetz.

Das Gesetz sagt:

Opfer von Krieg haben Schutz.

Bomben-Opfer haben Schutz.

Ihre Gräber haben Schutz.

Ihre Gräber müssen erhalten bleiben.

Darum:

Das Grab von Christian Meins ist geschützt.

Es ist bis heute da.

Es hat eine Grab-Platte.

Im normalen Kranken-Haus werden Zwangs-Arbeiter ermordet.

Sie werden auch beerdigt.

Auf dem Zentral-Friedhof.

Die Zwangs-Arbeiter haben Familien.

Die Familien bekommen keine Nachricht.

Die Familien wissen nichts über den Tod.

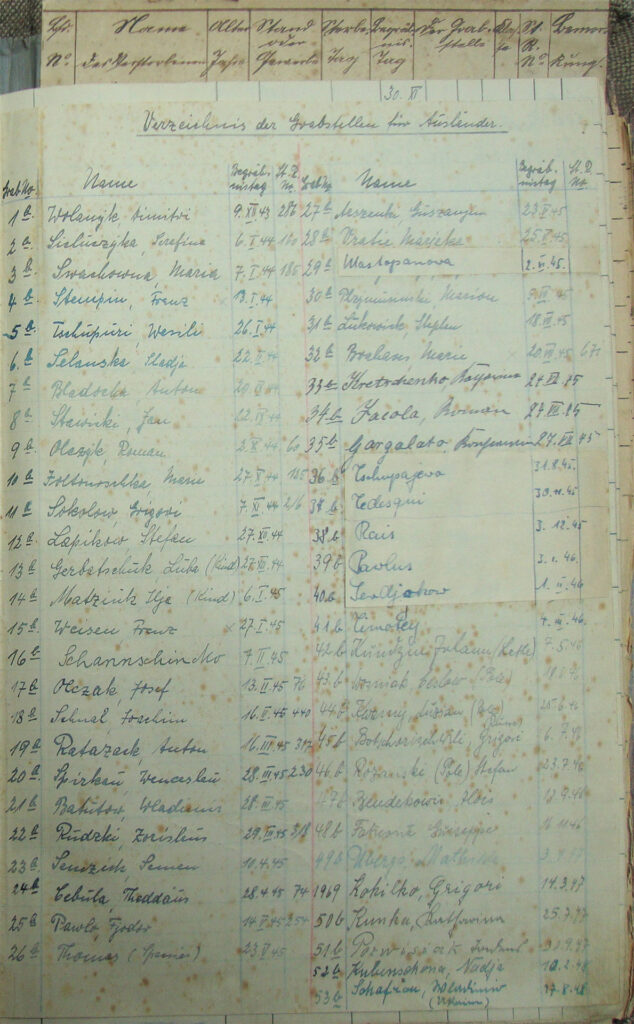

Erwachsene Erkrankte ausländischer Herkunft, die vor Dezember 1943 in der Heil- und Pflegeanstalt Lüneburg starben, wurden auf dem Anstaltsfriedhof wie Tote deutscher Herkunft behandelt. Das endete, als die Zahl ausländischer Erkrankter infolge von Zwangsarbeit, Lagerhaft und Flucht zunahm und sich die Sterbefälle häuften. Tote ausländischer Herkunft wurden ab 1943 auf einem eigens für sie ausgewiesenen »Ausländergräberfeld« beerdigt.

Es gibt immer Patienten aus dem Aus-Land.

Viele sterben.

Sie bekommen ein Grab auf dem Friedhof.

Da wo Platz ist.

Genau wie deutsche Patienten.

Bis zum Jahr 1943.

Ab dem Jahr 1943

gibt es mehr ausländische Kranke.

Weil:

Es gibt mehr Zwangs-Arbeit.

Es gibt mehr Lager-Haft.

Es gibt mehr Flucht.

Ab 1943 gibt es auf dem Fried-Hof einen Bereich.

Nur für ausländische Kranke.

Das Aus-Länder-Gräber-Feld.

Dort sind Gräber für ausländische Kranke.

Das ist ein Plan.

Auf dem Plan ist der Fried-Hof.

Und eine Liste der Namen.

Von den gestorbenen ausländischen Kranken.

Verzeichnis der Grabstellen für Ausländer im Begräbnisbuch für den Friedhof der Landes- Heil- und Pflegeanstalt Lüneburg mit Namensregister und Lageskizzen, 1922 – 1948.

StadtALg, FHA, 235.

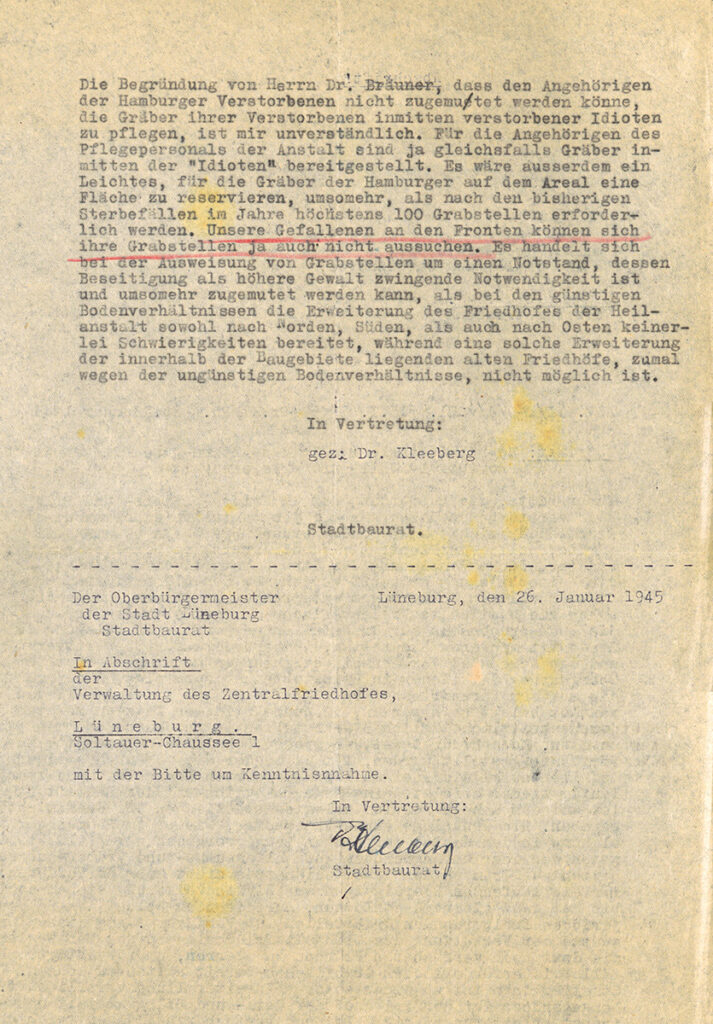

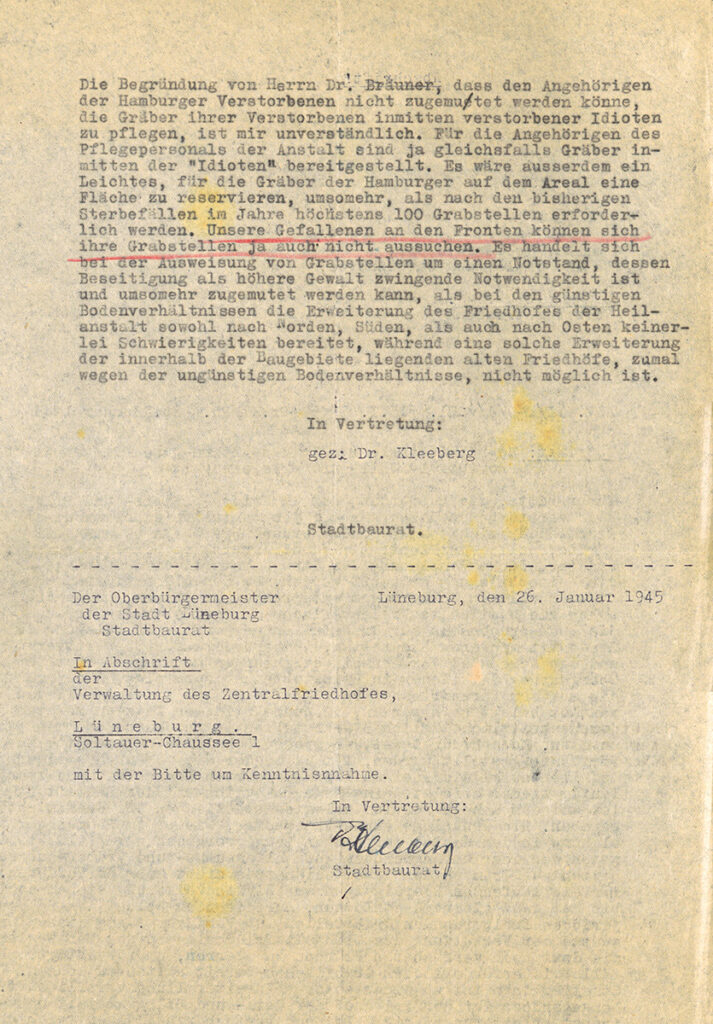

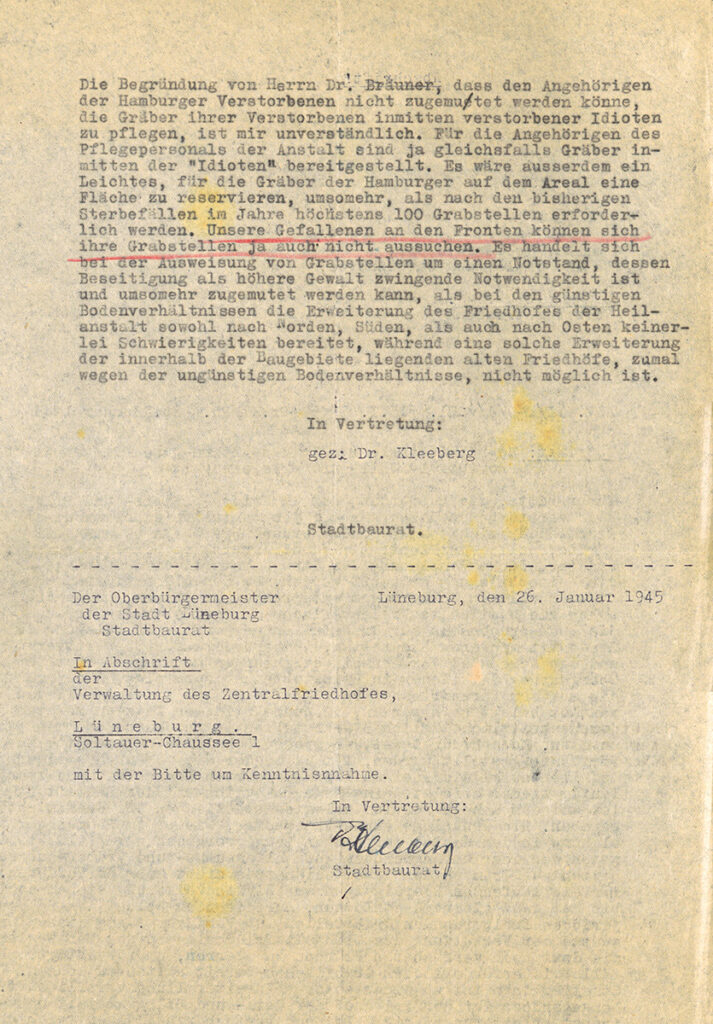

Wie wenig Wertschätzung Max Bräuner den Gestorbenen der Heil- und Pflegeanstalt Lüneburg entgegenbrachte, kann einem Brief entnommen werden, in dem es um die Ausweisung weiterer Gräberfelder auf dem Anstaltsfriedhof ging. Bräuner begründete seine ablehnende Haltung:

Das ist ein Brief.

Max Bräuner schreibt den Brief.

Auf den Friedhof sollen neue Gräber.

Für Menschen aus Hamburg.

Max Bräuner will keine neuen Gräber.

»[…] dass den Angehörigen der Hamburger Verstorbenen nicht zugemutet werden könne, die Gräber ihrer Verstorbenen inmitten verstorbener Idioten zu pflegen […].«

Auszug aus der Abschrift des Briefes von Stadtbaurat Kleeberg an das Amt für Volkswohlfahrt, Gauleitung Ost-Hannover, vom 26.1.1945.

StadtALg, VA1, 3054.

Max Bräuner schreibt:

Auf dem Friedhof sind Gräber von Kranken.

Aus dem besonderen Kranken-Haus.

Die neuen Gräber sind für Menschen aus Hamburg.

Familien aus Hamburg wollen die Gräber besuchen.

Er sagt:

Die Gräber der Toten aus dem besonderen Kranken-Haus stören die Familien.

Für Max Bräuner sind die Kranken wert-los.

Ihre Gräber sind wert-los.

Es wurde angeordnet, dass Erkrankte ausländischer Herkunft in der äußersten Randlage eines Friedhofs zu bestatten seien. Die Lage der Gräber der Opfer des Krankenmordes an Kindern und an Erkrankten ausländischer Herkunft ist heute vielerorts unbekannt. In Hadamar gab es ein als Einzelgräberfeld getarntes Massengrab, das 1945 geöffnet wurde. In Kalmenhof-Idstein konnten in 2020 die Gebeine von drei Jugendlichen und Kindern gefunden werden.

Ausländer-Gräber sind am Rand.

Ganz hinten in der Ecke vom Fried-Hof.

Es ist nicht bekannt wie es damals aussieht.

In Hadamar sehen sie aus wie Gräber für einzelne.

In echt sind es Gräber für ganz viele Tote.

Keiner weiß wo die Gräber der toten ausländischen Erkrankten sind.

Keiner weiß wo genau die Kinder-Gräber sind.

In Kalmenhof-Idstein findet man nur 3 Kinder-Gräber.

Das ist ein Foto.

Auf dem Foto sehen wir:

Ein Massen-Grab.

In Hadamar.

Es ist der Fried-Hof der Tötungs-Anstalt.

Viele Menschen sind zusammen in einem Grab.

Das gibt es auch an anderen Orten.

Fried-Höfe von anderen Tötungs-Anstalten.

Dort sind oft 2 oder 3 Leichen in einem Grab.

In Lüneburg wissen wir das nicht.

Der Fried-Hof wurde nicht untersucht.

Das Bild zeigt ein Massengrab der Tötungsanstalt Hadamar, 5.4.1945. Fotograf Ltd. Alexander J. Wedderburn (28. Infanteriedivision der US-Armee).

USHMM. PA 1071150.

DEALING WITH DEATH

Families had the opportunity to take the bodies or urns containing ashes home and bury them in their local cemeteries. At the Lüneburg institution cemetery, burial grounds were designated for children and for sick people of foreign origin. Many families saw death as a »release«. Shame also led to decades of silence in many families. Open mourning was rare. As a result, many relatives are only now learning about the fate of their loved ones.

Excerpt from the death register of the parish of Sülze, 1876 to 1945, page 172, No. 8A.

ArEGL.

Some families had the urns sent home from the killing centres in Brandenburg, Pirna-Sonnenstein and Hadamar. The ashes of the others were dumped, for example down a slope (Pirna-Sonnenstein). The urns of the victims of »Aktion T4« were buried in their home cemeteries at the request of their families. Many used existing family graves for this purpose. It was often the case that the families paid no attention to the dead.

»*18 April 1908 Sülze, died in Hadamar near Limburg/Lahn (state mental hospital)

(Hadamar Mönchberg (Lahn) registry office no. 238). Place of burial unknown (cremated) (at the request of the parents, no mention was made of the deceased in church).«

The urn containing Therese Schubert’s alleged ashes was transferred to Lüneburg and reburied in the central cemetery. The cemetery administration asked the family to report to the administration office regarding the dissolution of the grave. However, Therese Schubert’s son Theo placed the plaque on another grave and ignored the request. Since 2014, the grave has been on the list of historic graves in the city of Lüneburg and is therefore permanently protected.

The grave of Therese and Heinrich Schubert at the Central Cemetery in Lüneburg, 2014.

ArEGL.

Grave of Wilhelm Müller, 2016.

Obituary for Johannes Müller. Geestemünder Anzeiger, April 1941.

Privately owned by Helga and Ludwig Müller.

When Wilhelm Müller died, he was laid to rest in his son’s grave and a gravestone was erected. Johannes Müller was murdered on 7 March 1941 in Pirna-Sonnenstein. Because his family had the urn transferred, an urn containing his supposed ashes was not scattered on the banks of the Elbe, but was buried in the cemetery in Bremerhaven. The family also mourned their loved one publicly.

Graves at the Lüneburg institution cemetery, around 1945.

ArEGL 16-3.

Martha Ossmer’s parents photographed their daughter’s grave when they visited it after the funeral. Many families were unable to attend the funerals of their loved ones.

Private property of Christel Banik.

All graves in the institution cemetery were marked with a simple wooden cross. Often, it bore only the grave number or the name. The planting was simple. Relatives had the option of replacing the wooden cross with a stone at their own expense.

Excerpt from the burial register [for the cemetery of the Lüneburg mental hospital] from 1922 to 1948.

StadtALg, FHA, 235.

297 murdered children and adolescents from the Lüneburg »child euthanasia« programme were buried in two children’s graveyards at the institution’s cemetery. At least eight other children were buried there in scattered locations in adult graves due to a lack of children’s coffins. Children with families in Lüneburg were buried in the central cemetery at their parents‘ request. There are also murdered children whose graves remain unknown to this day.

Visit to the institution cemetery, approx. 1946/1947.

Grave of Ingeborg Wahle, 1945. The gravestone indicates 22 February as the date of death. However, she died two days later.

Private property of Renate Beier.

The parents of the murdered children often insisted on tending to the graves themselves, even though the province of Hanover covered the maintenance costs for all graves in the institution’s cemetery. Ingeborg Wahle’s parents travelled to Lüneburg several times a year to tend to their child’s grave. They also had the wooden cross replaced with a pillow stone. In the 1960s, it suddenly disappeared without the relatives being notified.

Although Inge Roxin’s parents had no money, they insisted on placing an obituary notice in the Lüneburg newspaper, inviting people to the funeral and burying Inge at the Central Cemetery at their own expense. From then on, her parents also took it upon themselves to pay for the upkeep of her grave. Inge was worth that to them.

Obituary for Inge Roxin, Lüneburg advertisements, October 1943.

Private property of Sigrid Roxin.

Christian Meins‘ grave at the Central Cemetery in Lüneburg, September 2021.

ArEGL.

Because he had been admitted as a »bomb-damaged child«, Christian Meins was not buried in the institution cemetery, but in the central cemetery in Lüneburg in a graveyard for bomb victims from Hamburg. In 1952, his grave fell under the War Graves Act. It has therefore been preserved to this day as a single grave with a gravestone.

The forced labourers murdered at Lüneburg Municipal Hospital were also buried in Lüneburg Central Cemetery. Their families were not informed of their deaths or burial locations.

Adult patients of foreign origin who died in the Lüneburg sanatorium and nursing home before December 1943 were treated like deceased persons of German origin in the institution’s cemetery. This ended when the number of foreign patients increased as a result of forced labour, imprisonment in camps and flight, and deaths became more frequent. From 1943 onwards, deceased persons of foreign origin were buried in a specially designated »foreigners« graveyard.

Directory of gravesites for foreigners in the burial register for the cemetery of the Lüneburg State Mental Hospital, with a register of names and location sketches, 1922–1948.

StadtALg, FHA, 235.

The lack of respect Max Bräuner showed for the deceased at the Lüneburg mental hospital can be seen in a letter concerning the designation of additional burial grounds at the hospital cemetery. Bräuner justified his negative stance as follows:

»[…] that the relatives of the deceased in Hamburg cannot be expected to tend the graves of their loved ones in the midst of dead idiots. […].«

Excerpt from the transcript of the letter from City Planning Officer Kleeberg to the Office for Public Welfare, Gauleitung Ost-Hannover, dated 26 January 1945.

StadtALg, VA1, 3054.

It was ordered that sick people of foreign origin were to be buried in the outermost edge of a cemetery. The location of the graves of the victims of the murder of children and sick people of foreign origin is unknown in many places today. In Hadamar, there was a mass grave disguised as a single grave field, which was opened in 1945. In Kalmenhof-Idstein, the remains of three young people and children were found in 2020.

The image shows a mass grave at the Hadamar killing centre, 5 April 1945. Photographer: Alexander J. Wedderburn (28th Infantry Division of the US Army).

USHMM. PA 1071150.

back

RADZENIE SOBIE ZE ŚMIERCIĄ

Rodziny miały możliwość zabrania zmarłych lub urn z prochami do domu i pochowania ich na lokalnym cmentarzu. Na cmentarzu zakładowym w Lüneburgu wyznaczono miejsca pochówku dla dzieci i chorych pochodzenia zagranicznego. Wiele rodzin postrzegało śmierć jako »wyzwolenie«. Ze względu na wstyd w wielu rodzinach przez dziesięciolecia panowało milczenie. Rzadko kiedy otwierało się żałobę. Dlatego wielu krewnych dopiero dzisiaj dowiaduje się o losie swoich bliskich.

Wyciąg z księgi zgonów parafii Sülze z lat 1876–1945, strona 172 nr 8A.

ArEGL.

Były rodziny, które poprosiły o przesłanie urn z domów śmierci w Brandenburgu, Pirna-Sonnenstein i Hadamar do swoich domów. Prochy pozostałych osób zostały wyrzucone, na przykład ze zbocza (Pirna-Sonnenstein). Urny ofiar »Aktion T4« zostały pochowane na cmentarzu rodzinnym zgodnie z życzeniem rodzin. Wiele z nich wykorzystało do tego istniejące groby rodzinne. Często zdarzało się, że rodziny nie zwracały uwagi na zmarłych.

»*18.4.1908 Sülze, zmarła w

Hadamar b. Limburg/Lahn (państwowy zakład opieki zdrowotnej i pielęgnacyjnej)

(urząd stanu cywilnego Hadamar Mönchberg (Lahn) nr 238). Miejsce pochówku nieznane (skremowana) (na życzenie rodziców

zmarłej nie wspomniano o niej w kościele)«.

Urna z rzekomymi prochami Therese Schubert została przewieziona do Lüneburga i złożona na cmentarzu centralnym. Administracja cmentarza wezwała rodzinę do zgłoszenia się do administracji w sprawie likwidacji grobu. Jednak syn Therese Schubert, Theo, umieścił tabliczkę na innym grobie i zignorował wezwanie. Od 2014 roku grób znajduje się na liście grobów historycznych miasta Lüneburg i tym samym jest objęty stałą ochroną.

Grób Teresy i Heinricha Schubertów na cmentarzu centralnym w Lüneburgu, 2014 r.

ArEGL.

Grób Wilhelma Müllera, 2016 r.

Nekrolog Johna Müllera. Geestemünder Anzeiger, kwiecień 1941 r.

Własność prywatna rodziny Helgi i Ludwiga Müllerów.

Kiedy Wilhelm Müller zmarł, został pochowany w grobie swojego syna i postawiono nagrobek. Johannes Müller został zamordowany 7 marca 1941 roku w Pirna-Sonnenstein. Ponieważ jego rodzina przeniosła urnę, urna z jego rzekomymi prochami nie została rozrzucona na zboczu Łaby, ale pochowana na cmentarzu w Bremerhaven. Rodzina publicznie opłakiwała swojego członka.

Miejsca pochówku na cmentarzu zakładowym w Lüneburgu, ok. 1945 r.

ArEGL 16-3.

Rodzice Marthy Ossmer sfotografowali grób swojej córki podczas wizyty po pogrzebie. Wiele rodzin nie miało możliwości uczestniczyć w pogrzebie swoich bliskich.

Własność prywatna Christel Banik.

Wszystkie groby na cmentarzu zakładowym oznaczono prostymi drewnianymi krzyżami. Często widniał na nich jedynie numer grobu lub imię zmarłego. Zazwyczaj nie umieszczano żadnych roślin. Krewni mieli możliwość zastąpienia drewnianego krzyża kamiennym na własny koszt.

Wyciąg z księgi pogrzebowej [cmentarza szpitala psychiatrycznego w Lüneburgu] z lat 1922–1948.

StadtALg, FHA, 235.

297 zamordowanych dzieci i młodzieży z programu »eutanazji dzieci« w Lüneburgu zostało pochowanych na dwóch cmentarzach dziecięcych na terenie cmentarza zakładowego. Co najmniej osiem kolejnych dzieci zostało pochowanych w grobach dla dorosłych z powodu braku trumien dla dzieci. Dzieci, których rodziny mieszkały w Lüneburgu, zostały pochowane na cmentarzu centralnym zgodnie z życzeniem rodziców. Są też dzieci zamordowane, których miejsce pochówku do dziś pozostaje nieznane.

Wizyta na cmentarzu zakładowym, ok. 1946/1947 r.

Grób Ingeborg Wahle, 1945 r. Na nagrobku widnieje data śmierci 22 lutego. Zmarła jednak dwa dni później.

Własność prywatna Renate Beier.

Rodzice zamordowanych dzieci często nie rezygnowali z samodzielnej pielęgnacji grobów, mimo że prowincja Hanower pokrywała koszty utrzymania wszystkich grobów znajdujących się na cmentarzu zakładowym. Rodzice Ingeborg Wahles kilkakrotnie w roku jeździli do Lüneburga, aby pielęgnować grób swojego dziecka. Zlecili również zastąpienie drewnianego krzyża kamiennym poduszkowcem. W latach 60. nagle zniknął, bez powiadomienia krewnych.

Mimo że rodzice Inge Roxin nie mieli pieniędzy, nie zrezygnowali z zamieszczenia nekrologu w gazecie Lüneburger Anzeigen, zaproszenia na pogrzeb i pochowania Inge na własny koszt na cmentarzu centralnym. Od tego momentu rodzice zobowiązali się również do opłacania kosztów utrzymania grobu. Inge była dla nich tego warta.

Nekrolog Inge Roxin, ogłoszenia z Lüneburga, październik 1943 r.

Własność prywatna Sigrid Roxin.

Grób Christiana Meinsa na Cmentarzu Centralnym w Lüneburgu, wrzesień 2021 r.

ArEGL.

Ponieważ Christian Meins został przyjęty jako »dziecko poszkodowane w wyniku bombardowania«, nie został pochowany na cmentarzu przy zakładzie, ale na cmentarzu centralnym w Lüneburgu, w kwaterze grobów dla osób poszkodowanych w wyniku bombardowania z Hamburga. W 1952 roku jego grób został objęty ustawą o grobach wojennych. Dzięki temu zachował się do dziś jako grób pojedynczy z płytą nagrobną.

Pracownicy przymusowi zamordowani w szpitalu miejskim w Lüneburgu również zostali pochowani na cmentarzu centralnym miasta Lüneburg. Ich rodziny nie zostały poinformowane ani o śmierci, ani o miejscu pochówku.

Dorośli pacjenci pochodzenia zagranicznego, którzy zmarli przed grudniem 1943 r. w zakładzie leczniczo-opiekuńczym w Lüneburgu, byli traktowani na cmentarzu zakładowym tak samo jak zmarli pochodzenia niemieckiego. Sytuacja ta uległa zmianie, gdy liczba pacjentów pochodzenia zagranicznego wzrosła w wyniku pracy przymusowej, pobytu w obozach i ucieczek, a liczba zgonów wzrosła. Od 1943 r. zmarłych pochodzenia zagranicznego chowano na specjalnie wyznaczonym dla nich »cmentarzu dla obcokrajowców«.

Wykaz miejsc pochówku cudzoziemców w księdze pogrzebowej cmentarza Landes-Heil- und Pflegeanstalt Lüneburg wraz z rejestrem nazwisk i szkicami lokalizacji, 1922–1948.

StadtALg, FHA, 235.

Jak mało szacunku Max Bräuner okazywał zmarłym z zakładu opieki psychiatrycznej w Lüneburgu, można wywnioskować z listu dotyczącego wyznaczenia kolejnych miejsc pochówku na cmentarzu zakładowym. Bräuner uzasadnił swoje negatywne stanowisko:

»[…] że nie można oczekiwać od krewnych zmarłych z Hamburga, aby dbali o groby swoich bliskich pośród zmarłych idiotów […].«

Fragment kopii listu urzędującego architekta miejskiego Kleeberga do Urzędu Opieki Społecznej, kierownictwa okręgu wschodniego Hanoweru, z dnia 26 stycznia 1945 r.

StadtALg, VA1, 3054.

Zarzono, aby osoby chore pochodzenia zagranicznego chować na skraju cmentarza. Lokalizacja grobów ofiar zabójstw dzieci i osób chorych pochodzenia zagranicznego jest dziś w wielu miejscach nieznana. W Hadamar znajdował się zbiorowy grób zamaskowany jako pole pojedynczych grobów, który został otwarty w 1945 roku. W Kalmenhof-Idstein w 2020 roku znaleziono szczątki trzech nastolatków i dzieci.

Zdjęcie przedstawia masowy grób w ośrodku zagłady Hadamar, 5 kwietnia 1945 r. Fotograf: Alexander J. Wedderburn (28. Dywizja Piechoty Armii Stanów Zjednoczonych).

USHMM. PA 1071150.